ALL WORK AND ALL PLAY: Francisco 'Baby' Pignatari

Originally published in Issue 41 of The Rake, James Medd writes that Francisco ‘Baby’ Pignatari was not your average playboy. True, he enjoyed plenty of sexual conquests, and was harshly dismissive of some of the women in his life. He embraced danger and lived his life, as it’s said, ‘to the full’. But one thing set him apart: all the cash he burned through at night he earned through hard work during the day.

Playboys should not be complicated. However thick the veneer of sophistication, their very essence is to obey their natural instincts. Francisco ‘Baby’ Pignatari was the exception. He raised questions — chief among them: How? As in, how did he do it? When it comes to Porfirio Rubirosa, the Aga Khan or Pignatari’s other rivals from the postwar golden age of the international playboy, the answer is simple enough: others paid (either parents or lovers or both). But when Baby wrote off a speedboat, hired a plane to fly halfway around the world to amuse a new girlfriend, or rented eight suites at Paris’s Georges V, he paid for it himself.

And this was not with money made by wandering in front of a camera or applying a splash of paint to canvas. At the height of his international misadventures in the 1950s and sixties, when he had a glass engraved with that unfortunate nickname (the gift of an English nanny) in every club in any city in the world worth visiting, Baby was running Brazil’s third-largest business, employing 10,000 workers, responsible for multi-million deals, strategy and investment in new markets. Again: how? At home in São Paulo, the police chief long believed there were in fact two Pignataris: the hard-working industrialist Francisco and his spoiled playboy son Baby. Perhaps, on one level, he was right.

One of the secrets of Baby’s success was his ability to do without sleep. He never wasted more than four hours a night unconscious. During the remaining 20, he barely kept still. To call him a man of action would be like labelling an atomic bomb a potential hazard: it was simply what he was for. “I must do something dangerous when I feel restless,” he confided to Life magazine in 1958, going on to explain that he felt restless all the time. “I don’t like watching other people do anything. I only want to do things myself. If you are sitting at this table talking to someone else, I will not hear you. I only hear when I am talking.”

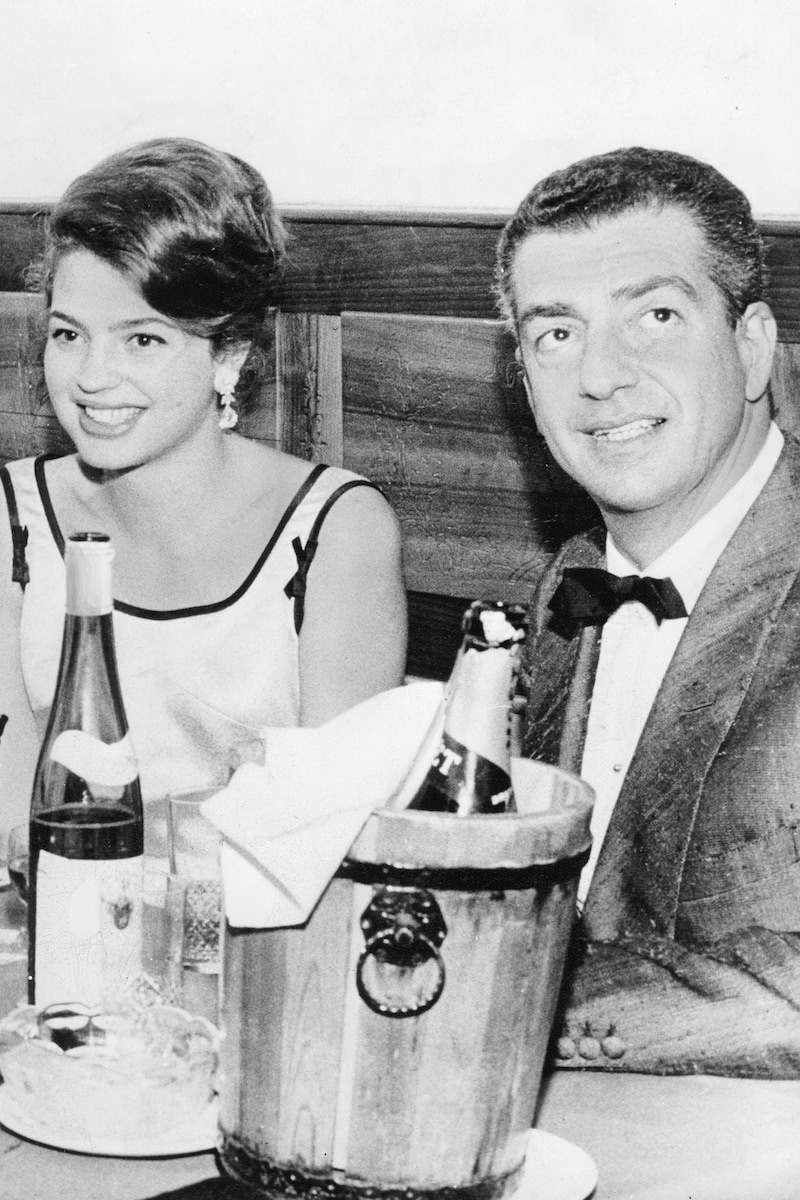

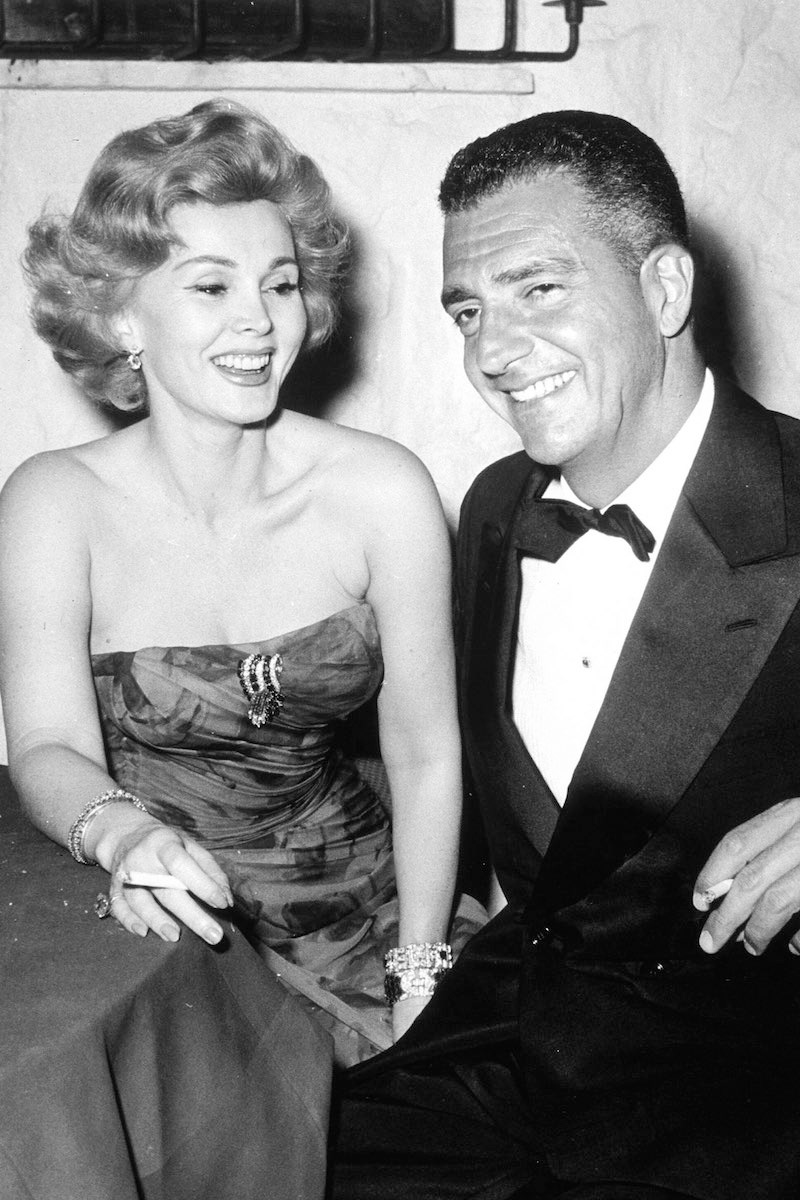

Fortunately, women were ready to listen. Strings of what the gossip magazines then called ‘starlets’, from Sweden, France and Japan, as well as models including Barbara Cailloux and Melissa Weston, kept him busy between longer affairs and four marriages. It was understandable. Even ignoring the very real attractions of wealth, power and ambition, Baby was 6ft 3in, darkly handsome, and could carry off any style of clothing from swimming trunks to dinner jacket, bowling shirt to mechanic’s overall. And with this came, in the words of Richard Gully, Baby’s upper-crust English ‘social secretary’, a certain look. “A very glamorous woman summed up Baby’s personality,” said Gully, an illegitimate cousin to British Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden, erstwhile publicist for Hollywood magnate Jack Warner, and out-and-out rogue. “She told him, ‘You have the most indecent eyes of any man I’ve ever met’.”

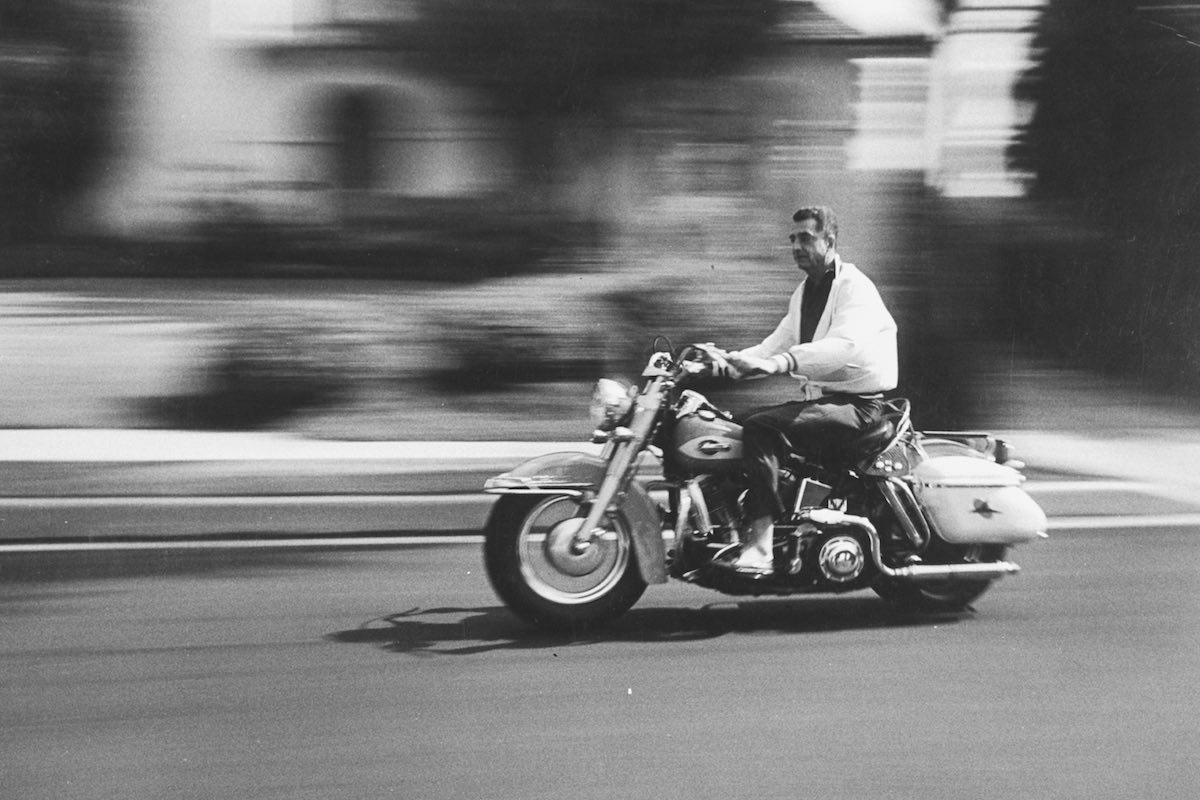

Another of Baby’s U.S.P.s, according to Gully, was his taste for danger. “He drives fast, he flies his own airplane, he skis, and he can swing from a trapeze,” Gully said. “Most men have a tendency to play it safe, but women like a man who lives dangerously.” The trapeze was perhaps overplaying it, but Baby was by any standards a daredevil. Particularly celebrated was the night he left the Oasis, his São Paulo local, with that evening’s partner in the passenger seat of his Cadillac, and drove into a telephone pole. When his companion noted that the obstruction was still standing, he backed up, hit the accelerator and finished the job — pole and car. He managed to write off another Cadillac in one go by attempting to drive it through the revolving door of a bar. Another favourite trick was to jerk his steering wheel to one side so that his car was travelling solely on its right- or left-hand wheels. With motorbikes, it was to ride while lying fully prone — famously, from Avenue Foch to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris — or while standing up, in which fashion he made his entrance at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival.

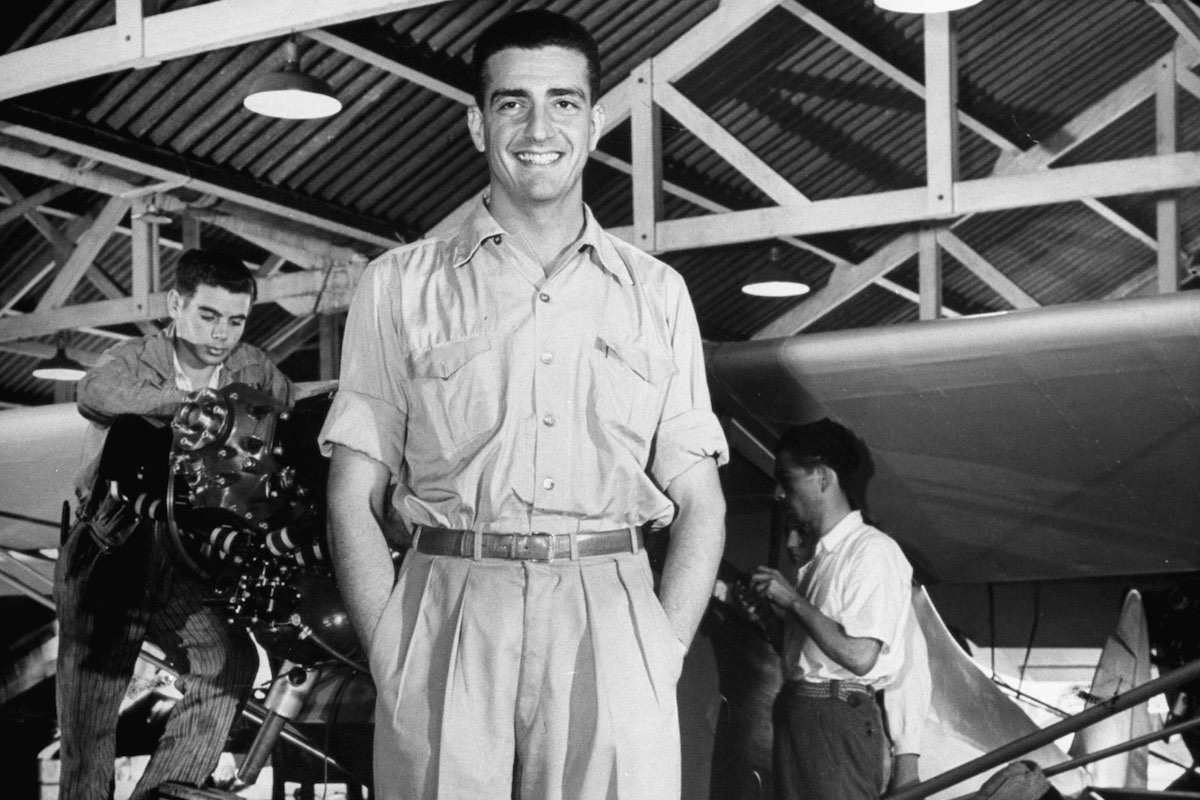

Aeroplanes were another hobby. He was Brazil’s youngest pilot, flying solo after just four hours’ instruction at the age of 18. Chiefly, he took to the skies to buzz high buildings or beaches, the fuller the better. He would also terrorise sunbathers from the sea, turning his speedboat direct for the beach, opening the throttle and then turning at the last moment on a wave to head back out for the horizon. When this went wrong one time on Santos beach, he was rescued from the remains of the splintered boat by swimmers and taken to hospital, where his wounds were so severe he had to be stitched up without anaesthetic. He was, naturally, out on the town the same night.

Every bit as extreme as his recklessness was his extravagance. Actress Tracey Morgan, whose career was to peak with the role of ‘Girl in Booth’ in the Elvis vehicle Jailhouse Rock, was nonetheless sufficiently important to Baby to receive orchids encrusted with pearls. Dolores del Rio, rather more successful (though, at 46, also considerably older), earned an entire planeload of flowers. On his first encounter with Linda Christian, later to become one of the great passions of his life, he reacted to the news that she had just lost a Chinese jade earring with an offer to take her to Hong Kong to buy a replacement. You wouldn’t have to be Richard Gully to believe he meant it.

Somehow Baby’s dedication to spending money was matched by a dedication to making it. He was proud to have made his own fortune, but to call him a self-made man would not be strictly accurate: his grandfather on his mother’s side was Count Francesco Matarazzo, founder of Brazil’s greatest industrial firm. Baby even inherited a business, though this was the much smaller steel mill founded by his father, Giuilio Pignatari, an ophthalmologist who died in 1936, when Baby was just 19.

In six years he increased the workforce 25-fold, and expanded his interests into copper and bauxite mining, machine-gun manufacture, aeronautics, even retail. In 1958 he was making $2m a year, fuelled in part by a desire to outdo his maternal family, whose treatment of their workers, and his own father, he despised. Baby was angry, his contempt extending also to those who judged him for his playboy lifestyle. “I know those Wall Street men with their little neckties and their little hats,” he told Life. “They get drunk, too, when they think nobody is looking. They sneak off with women I wouldn’t spit on. But the next morning they look down their long noses at me.”

It’s tempting to cheer his rage when applied on this scale, but the darkness ran through his romantic as well as business affairs. In his own mind, Pignatari’s motivation was clear: “When I stop being interested in beautiful women,” he said in 1959, “I’ll be dead.” But perhaps the ‘why’ was every bit as complicated as the ‘how’. When he tired of his latest conquest, as he always did, he could be astonishingly brutal in his dismissal. His second wife, Nelita Alves de Lima, was simply told one morning to be gone before he returned from the office. When Linda Christian outstayed her welcome in Rio, he hired 20 taxis full of locals to let off fireworks outside her hotel and wave banners saying ‘Linda Go Home’. “It was very funny,” he recalled. “The traffic was jammed for seven blocks in every direction.”

And he was certainly not above violence — the musicians of the Oasis were well accustomed to finding their instruments used as weapons against someone who had looked at his Martini in the wrong fashion. Whether he also beat his women is a moot point, but his interest seldom extended beyond his own needs. “I’ll never understand women,” he complained. “Once I’m nice to them, they behave as if I was their property.”

Strange, then, that he married at all, let alone four times — his final divorce, in October 1977, came a mere 20 days before his death. Perhaps he tried, in his own way, to be faithful. For Nelita he gave up the speedboats, motorbikes and planes and attempted to recreate a new playboy habitat by constructing a million-dollar home outside São Paulo with a shooting gallery, bowling alley, two Turkish baths, and a 130-foot outdoor pool that ended in a 21-foot waterfall behind which lay a hidden grotto with bar, bath and bed. The marriage was finished before the house.

His third marriage, four years later, was to Ira von Fürstenberg, then 20 to his 45, and married to Prince Alfonso von und zu Hohenlohe-Langenburg. In Mexico City, the pair were arrested in a dawn raid for adultery, prompting Baby to comment of his rival, “I may not have a title, but at least I have honour.”. (He did, however, claim that he had been assisting her with her business affairs.)

Fürstenberg was to recall him telling her, “Remember that you are born and you die alone”. It might have been his abiding rule for life, yet in his final years he became a great patriot, and announced in 1973 that he would hand over his business to the Brazilian state after his death. Really, too complicated for a playboy.

This article originally appeared in Issue 41 of The Rake.