BADMAN FOREVER

Randolph Scott was once synonymous with the classic ideal of American manhood: steely, forbearing, straight-shootin’. But off screen, his lifestyle as a sharp-dressin’ gentleman-financier set a template for Hollywood to follow.

In Thomas Pynchon’s debut novel, V, published in 1963, the anti-hero, a discharged and feckless U.S. navy sailor named Benny Profane, is watching an unspecified Randolph Scott western and comparing himself unfavourably to its square-jawed, morally righteous hero: “He was cool, imperturbable, keeping his trap shut and only talking when he had to — and then saying the right things and not running off haphazard and inefficient at the mouth.”

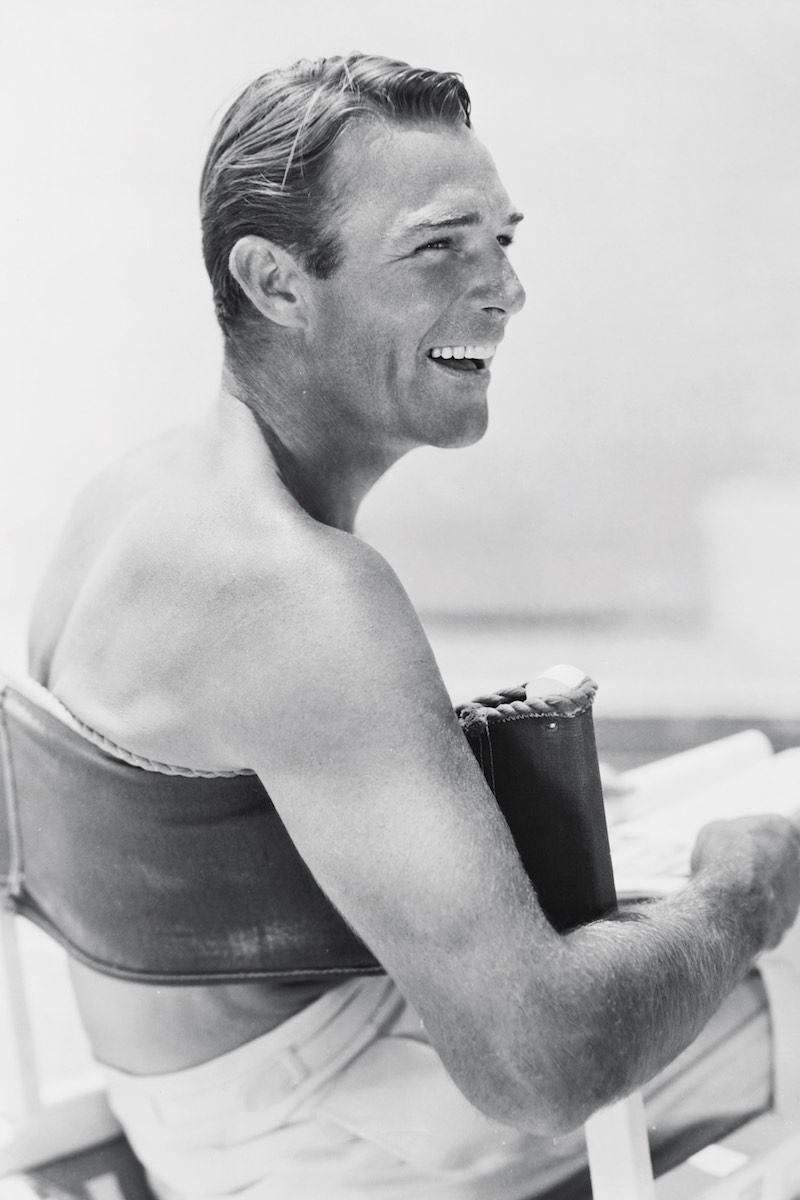

Profane’s admiring analysis was shared by a generation of post-second-world-war moviegoers: though Scott never won an Oscar, his lanky, laconic cowboy archetypes — reticent but resolute, diffident but dauntless, potent but private — made him one of the top box-office stars of the late 1940s and early fifties. In the 39 westerns he starred in, from 1946’s Badman’s Territory to 1962’s Ride the High Country, he not only created an image of bruised-but-unbowed integrity that became, for many, synonymous with an ideal of American manhood, he paved the way for the generation of be-saddled exemplars who followed him, from John Wayne’s doughty sheriffs to Clint Eastwood’s enigmatic Man with No Name. He took a refreshingly what-the-heck view when it came to the possibility of typecasting. “I believe in letting well enough alone,” he told the Hollywood gossip maven Hedda Hopper in a rare interview. “I’m not looking for new fields to conquer. Westerns are the mainstay of the industry. And they always make money.”

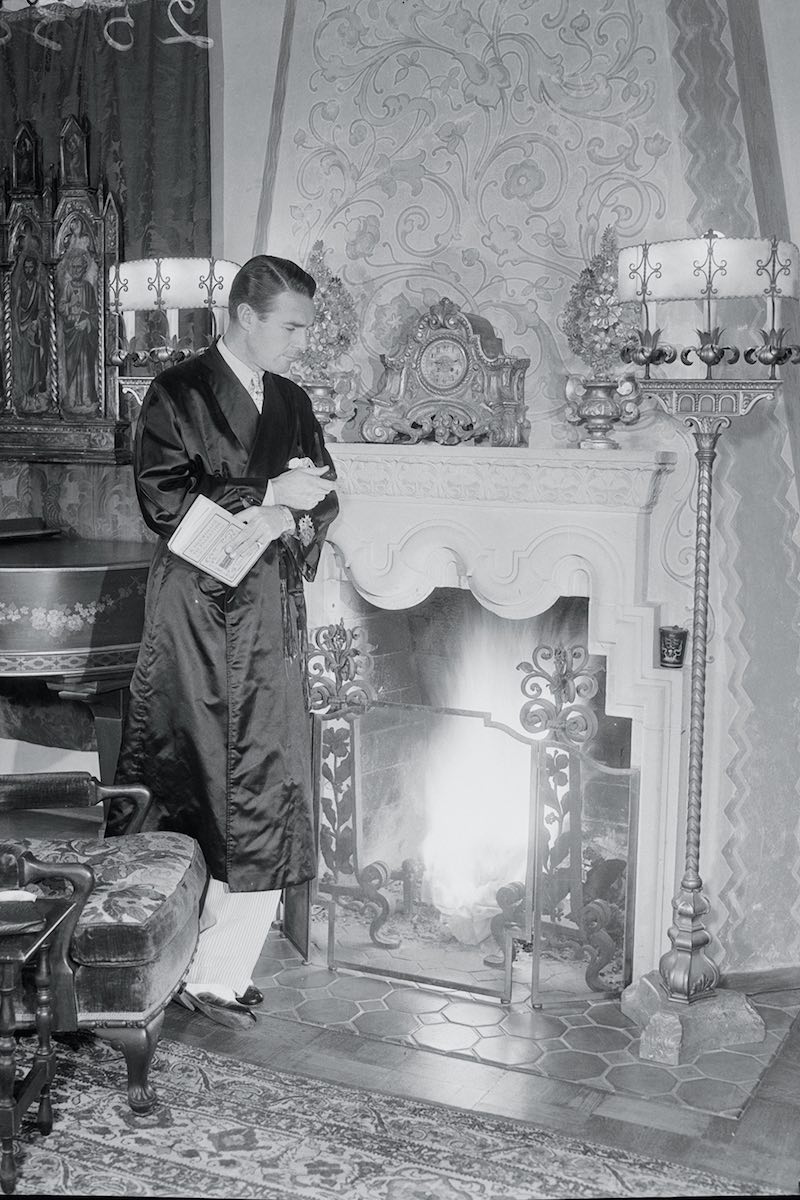

The latter consideration was not incidental to Scott, whose off-screen demeanour was more white shoe than cowhide boot. He was one of the first actors to form his own production company, in the 1940s, when most stars were under contract to major studios, and was thus one of the first to have a measure of control over his output and its profits; he eventually amassed a fortune worth a reputed $100m, with holdings in real estate, gas, oil wells and securities, and he had the accoutrements to match. “There was not one item about his place to suggest he’d ever appeared in a western,” Hopper reported after interviewing Scott at his Burton A. Schutt-designed, mid-century-modern-exemplifying home, which was emphatically not on the range but in the heart of Beverly Hills. She added: “Randy, dressed in sports clothes, looked about as western as the Brooklyn Bridge.” Lee Marvin, meanwhile, recalled Scott’s sitting on a film set, unimpeachably tailored, while his stunt man trundled by in a burning stagecoach. “He didn’t even look up,” Marvin marvelled. “Just went on reading the Wall Street Journal.”

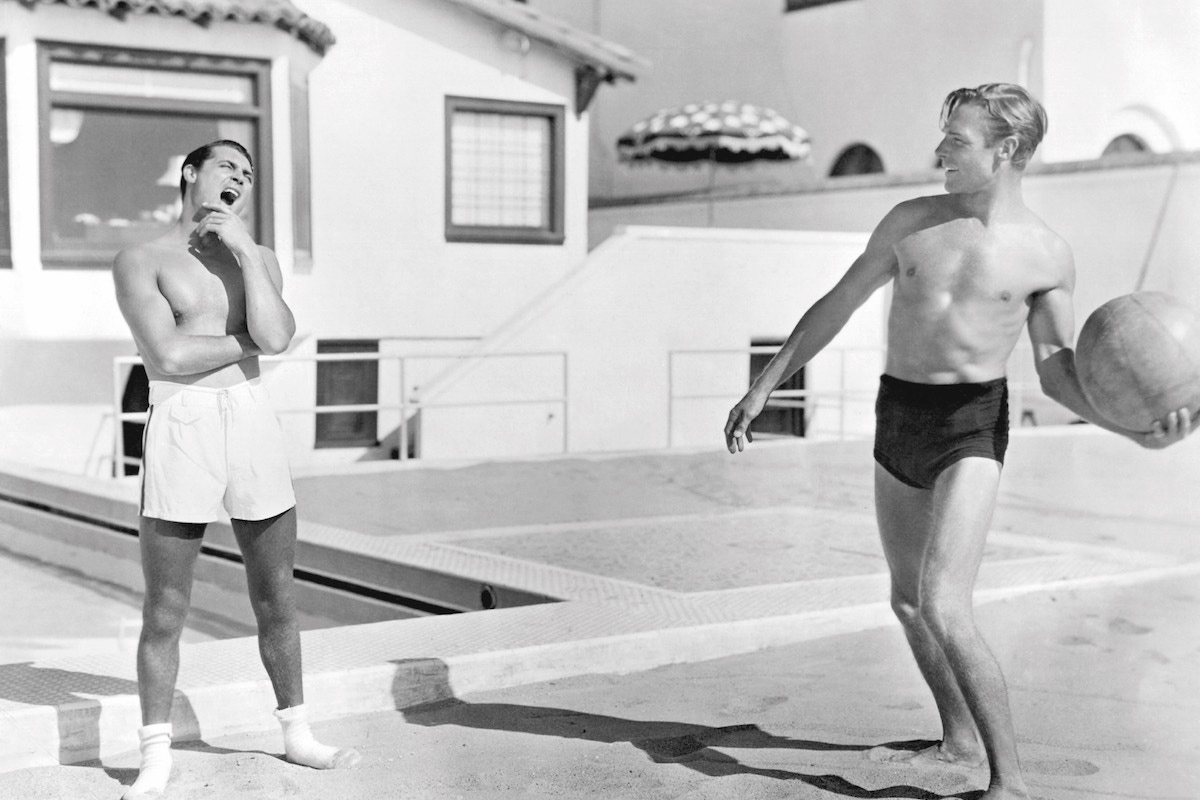

If the Virginia-born Scott liked to cultivate an image of the well-bred, French-cuffed, patrician southern gentleman-financier when out of his 10-gallon hat — he was reportedly the only actor accepted into the august environs of the Los Angeles Country Club — there was one trait he shared with his hardscrabble heroes: a wary reserve. “Frankly, I don’t like publicity,” he said in a 1961 interview. He always kept in mind a saying of the Broadway impresario David Belasco: “He told his clients, ‘Never let yourself be seen in public unless they pay for it’. To me, that makes sense.” Scott may have felt he’d already paid enough out of his own pocket after a prolonged house-share with Cary Grant — 12 years on-and-off, spanning the mid thirties and forties, in a Santa Monica beachfront property dubbed ‘Bachelor Hall’ — gave rise to rumours of a more-than-platonic relationship between the pair. “He was my best friend,” Scott said when Grant died in November 1986 (Scott would follow three months later). “And that’s all I have to say about that.”

Scott hailed from the kind of background where ‘imperturbable’ was regarded as the ultimate approbation, and discretion was always the better part of valour. He was raised in Charlotte, North Carolina, the only son in a family of six; his father, George, was an administrative engineer at a textile company, while his mother, Lucy, came from the kind of wealth that propelled Scott into the best prep schools and, eventually, the University of North Carolina, where he studied textile engineering with a view to entering his father’s firm. However, the idea of a desk-bound life soon began to pall for the athletic, six-foot-two Scott, who excelled at football, swimming and sailing, and who lied about his age in order to enlist in the military during world war I, during which he served in France. On his return, he embarked on a California road trip with a friend, equipped with a letter of introduction to the eccentric millionaire and studio head Howard Hughes, courtesy of a family connection, asking if they could tour a backlot or two. Hughes went one better. “He suggested we work on a picture for a few days,” Scott later recalled, “so we became extras in a saloon scene in a movie called Sharp Shooters.”

Read the full story in Issue 73, available on TheRake.com