Big things for Bourbon

It’s the stuff of cowboy movies and saloon bars. It’s what noir detectives keep in their desk drawer. It’s was the tipple of choice for Sinatra and his pack and the drink that fueled Madison Avenue in its heyday. It’s defiantly masculine. But - move over Scotland - it’s not whiskey. It’s close, but by law bourbon - the booze that built America - must be at least 51% corn, distilled at less than 160 proof and aged for at least two years in new, charred white oak barrels. It’s these barrels which are often then bought to mature the other stuff north of the border.

What’s more, bourbon must be made in the United States - something defined by an act of Congress 55 years ago this year. Call your foreign version what you like, but you cannot call it bourbon - even though the name, by various turns, has its origins in the 18th-century France. Early American colonists - in thanks to the French royal family, the House of Bourbon, for its assistance in the fight against the British - named a vast area of Kentucky ‘Bourbon County’, an area that, then and now, just happened to be the centre for whiskey-making. Bourbon came to be a generic name for any whiskey out of the region and, later, out of just about anywhere on the Continent.

There’s little that’s generic about the product today though, as drinkers are slowly discovering. Sales in the US are up around 7% year on year and in the UK are rising around 14%, with predictions having it that bourbon will be the fastest growing spirit worldwide within the next four years. Indeed, bourbon has gone through an image reappraisal - from rough and ready to connoisseur’s liquor-of-choice - of the kind that has seen Scotch lose some of its fuddy-duddiness, with a concomitant increase in understanding too. Bourbon is no longer automatically drowned in cola. And, if it’s mixer-free, drinking has moved on from shot to sip.

Sure, there’s been some marketing spin - time was when you couldn’t buy a bourbon in a presentation box, but the industry has now taken its lead from the Highlands on that score - and the Japanese have certainly given the market a shot in the arm by extending their otaku interest from Scotch to bourbon. But the drink - which saw many of its historic makers shut down by prohibition in 1920 yet never recover when the law was repealed in 1933 - has largely been rescued by its being taken up as part of the last decade’s great American craft revival, which subsequently saw the launch of small batch premium versions. Like homegrown jeans brands and watchmakers, beers and leather-goods, bourbon has got Stars ‘n’ Stripes cool.

Some 50 have been launched, or relaunched, over the last decade - from Bulleit to W. L. Weller, Heaven’s Hill to King’s County, from the pricey if esteemed Michter’s to the wonderfully named Pappy Van Winkle - each with its own balance of more or less rye (the more the bitter) and wheat (the more the sweeter). Bourbon buffs are even using language more typically heard rhapsodising the subtle aromas and gastronomic delights of wines to describe these new bourbons: Basil Hayden’s is said to have hints of tea and peppermint, Baker’s of toasted nuts and vanilla, Elijah Craig Barrel Proof notes of black pepper and butterscotch...

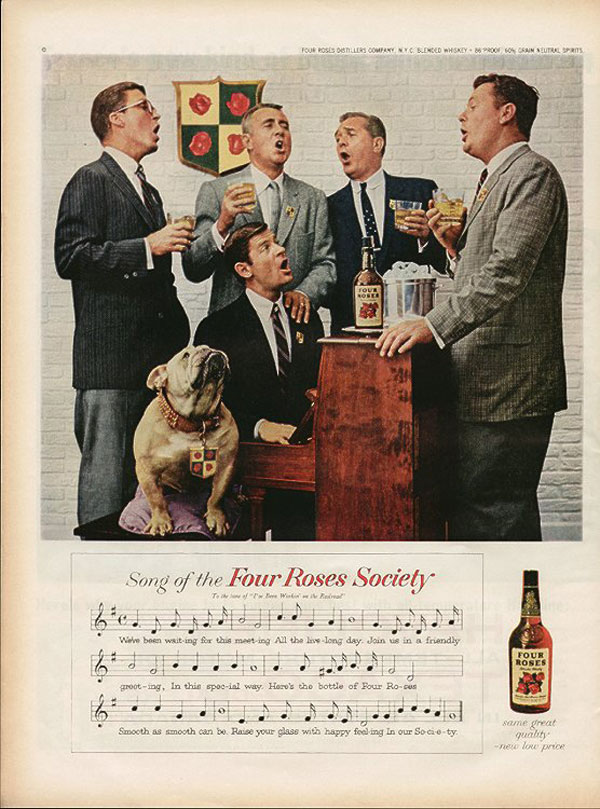

It’s these same buffs who get inebriated over the particularities of history and production - that, for example, Maker’s Mark is made in batches of less than 19 barrels at a time and is based on a recipe that dates back to 1780; that Baker’s, created by Jim Beam’s grand nephew Baker Beam, requires the use of a special yeast and is aged for seven years; that the 130th anniversary edition of Four Roses - along with Old Forester, one of Philip Marlowe’s two bourbon brands of choice - was deemed this year’s World’s Best Bourbon by the World Whiskies Awards.

That most bourbon makers are cheek-by-jowl in Kentucky’s ‘Bourbon Belt’ is less because the state is bourbon’s spiritual home, but because the local water, rich in limestone, filters out most of the unpleasant-tasting iron, leaving the drink’s distinctive taste - a balance between the wood char and the corn sweetness. But, for all the variety, bourbon remains a proper home brew. Distillation takes place in continuous stills using what is called the sour mash process, by which part of the previous day’s mash is used - instead of water - to start the next fermentation process. After distillation nothing can be added but distilled water. The subtle differences between bourbons are a product of simple measures - adding rye to the mash mix gives a more mellow rounded flavour, adding barley a drier, spicier flavour. And the more the barrel in which it matures is charred, the woodier the taste.

Maturation is suitably speedy too. Actually straight bourbon whisky must be aged for a minimum of just one year, Kentucky bourbon - generally considered the real McCoy - for two. Yes, whether it’s sales fluff or full flavour, it’s the older bourbons that command the serious up-front prices, with the likes of A. H. Hirsch Reserve 16-Year-Old Straight Bourbon Whiskey or Parker’s Heritage Collection 2nd Edition 27-Year-Old Small Batch Bourbon commanding £2400 and upwards a bottle. But don’t assume the older a bourbon is, necessarily the better it is to actually drink: flavours get more complex but also more astringent.

Likewise, don’t wait around too long for this renaissance market to mature. There’s a reason why bourbons - especially those for pre-prohibition examples, which are as much expressions of the United States’ history as something anything one might actually drink - are starting to appear at auction. American whiskies are being identified as a smart investment opportunity. If you happen to have a bottle of Old Crow Bourbon from 1912, try not to open it without there being a very, very good reason to celebrate. The original Old Crow plant became what today is the distillery for Woodford Reserve. Both used the same water for their bourbons. But whereas a fine bottle of Woodford will cost you £30, that bottle of Old Crow would see you spending something like £7,500. And cheers to that.