BLOND AMBITION

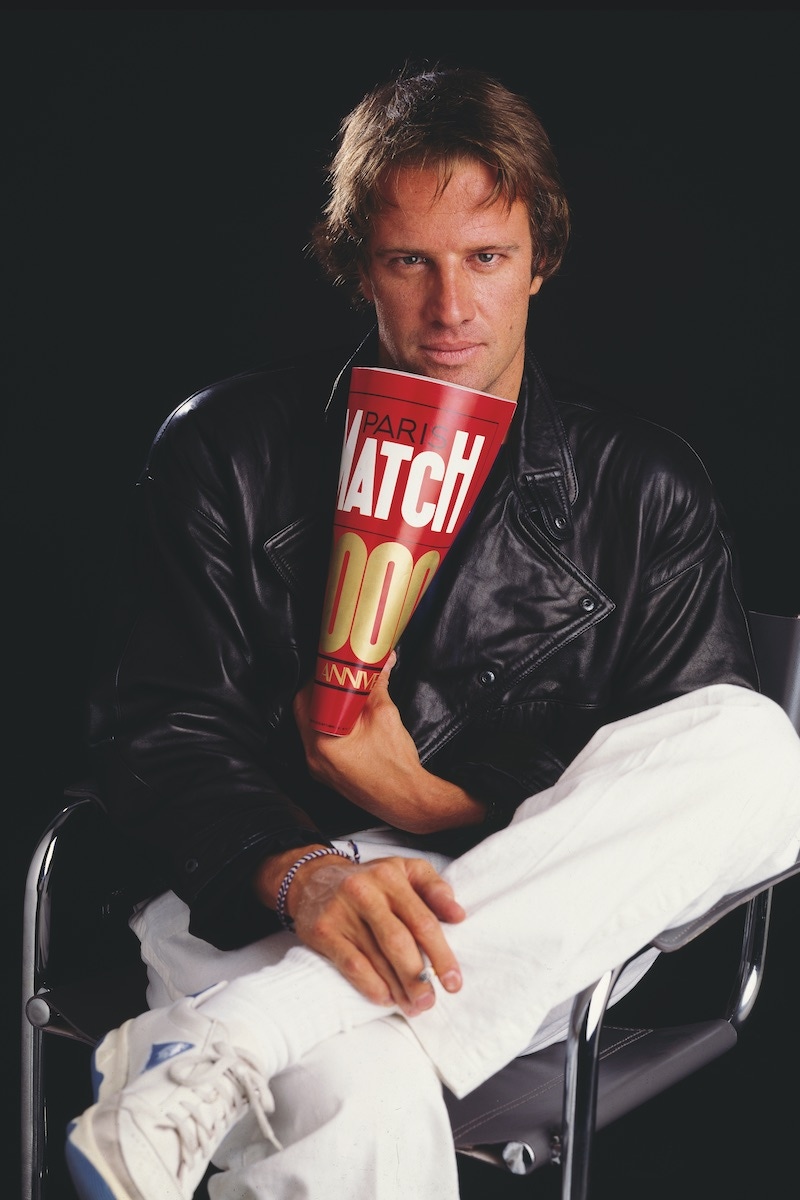

Christophe Lambert, the New York-born French actor with a ‘timeless quality’ in his eyes, was synonymous with the style and cachet of the eighties. So much so, in fact, that when the nineties dawned, Lambert’s star was left looking a little worse for wear.

The French excelled in the eighties. Pastels, big shoulders, and the triumph of smart-casual played to their fashion strengths, of course, but the emphases on exaggerated urban sophistication and free-floating existential angst were so up their allée the entire decade might as well have been flying the tricolore.

While the pop music of the era was merely pretending to be French (bonjour, Nick Rhodes, Ben Volpeliere-Pierrot and all those jazzy female vocalists in Breton smocks), the films didn’t have to. For at least a brief period in the eighties, France’s cinema was at the vanguard. Le cinéma du look, as it was called, seized the zeitgeist with a mix of urban alienation (let’s not forget the constant threat of nuclear war and the reality of western industrial decline) and glossy image-making (…but these banking bonuses and shoulder pads will help us forget it all). Bequeathing a poster-friendly theme to student rooms across the continent in this short-lived parade were Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Diva, Léos Carax’s Les Amants du Pont Neuf and, by some way the most far-reaching, Luc Besson’s Subway.

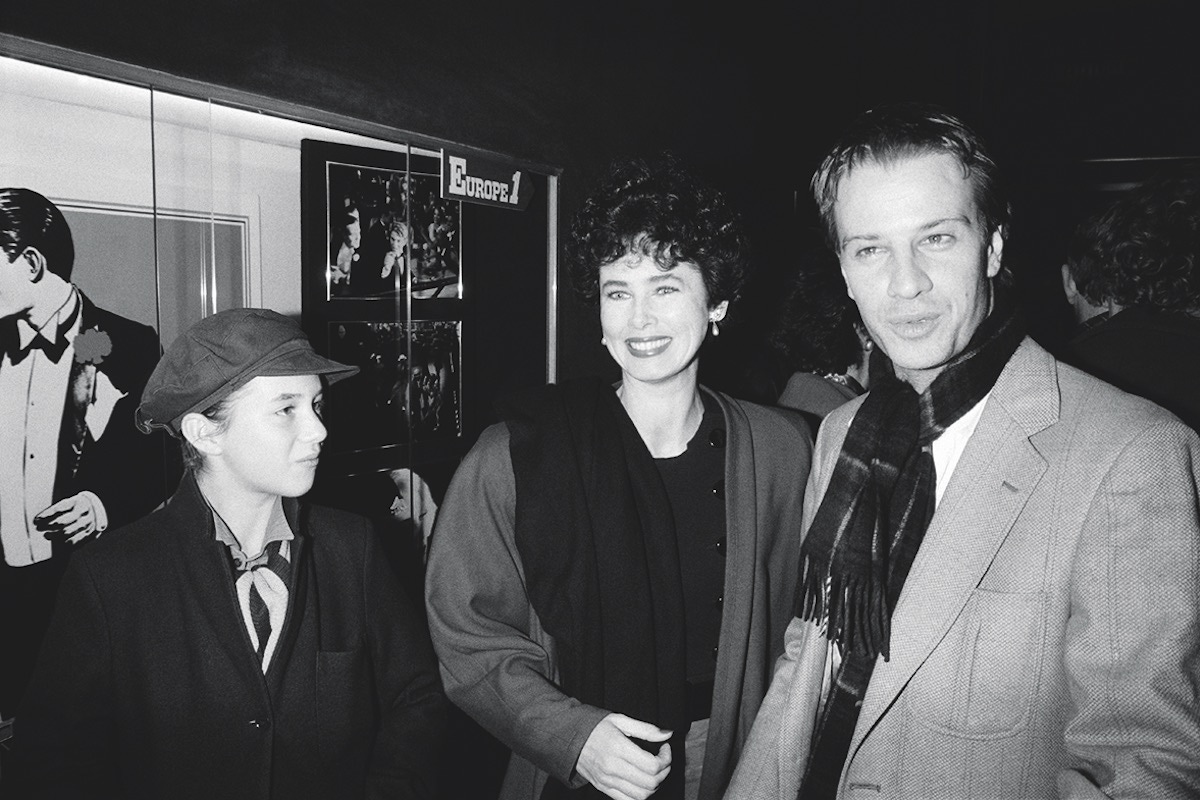

A pretty silly tale of a group of Parisian buskers and thieves living in the city’s underground system, Subway’s marriage of unexplored ennui, glossy funk-rock and evening dress came at the perfect time: by 1985, the decade was fully and gloriously convinced of its own importance. Among the cast were future star Jean Reno and established diva Isabelle Adjani, but no one noticed them. We were all too busy looking at Christophe Lambert. With his bleached-blond movie-punk hair, dinner jacket and unflustered nihilism, he was the European answer to Richard Gere’s American Gigolo. The fact that his character, Fred, barely spoke only made him more perfect.

For most of the world, it had been a while since a Frenchman — even one, like Lambert, born in New York — had been an emblem of cool. For the French, though, he had a familiar air: with his close-set eyes and heavy brow, Lambert was a ringer for Jean-Paul Belmondo, the star of 1960s nouvelle vague pearls including A Bout de Souffle. His version of Belmondo’s simian features was tidier and more conventionally beautiful, but it can only have helped him secure his breakthrough role as Tarzan in Greystoke, released a year before Subway.

Greystoke director Hugh Hudson, recalling the casting, identified another aspect of Lambert’s appeal. He plucked him from the audition line-up, he said, because of a “strange quality” in his eyes. This, one of the actor’s defining qualities, turned out to have a rather mundane cause, as the director discovered: “Somehow, because he was myopic, when he took his glasses off, he couldn’t really see properly, so he would seem to look through you into the distance.”

Chosen as king of the jungle, the bespectacled nine-stone weakling was built up into a 14-stone rippling gymnast over six months and a series of ape-acting workshops. Though this was new, he was by then reasonably experienced. After a childhood moving with his French diplomat father from New York, where he was born in 1957, to boarding school in Geneva and then Paris, he was eased into banking in London, but managed to wriggle his way out and into the prestigious Conservatoire de Paris. Though he consistently paints his career as a series of lucky breaks, handed to him almost against his will, acting was the only career he wanted.

Completing his ascent to emblematic status was 1986’s Highlander, another time-capsule-worthy piece of eighties cinema. Directed by Russell Mulcahy, an Australian who had made his name in music videos, including the state-of-the-art pomp and grandeur of Ultravox’s Vienna and Duran Duran’s Rio, this muddle of fighting and pouting had Lambert alongside Sean Connery as a pair of immortal swordsmen battling a perpetual nemesis through time and fiendishly poor dialogue. Again, it was the gaze that did it. “His eyes had a timeless quality,” said Mulcahy, reminiscing on the 30th anniversary of his strangely enduring creation.

Unfortunately, where Subway had allowed Lambert’s presence to do the talking, here he was given a challenge to which he simply couldn’t rise: a Scottish accent. From the safe distance of 30 years of cult success, he told one interviewer that his agent had been canny enough to sign him for the film before the studio realised that, despite his legal status as both Christopher and Christophe, he spoke English “like Inspector Clouseau”. Daily four-hour dialect coaching did little to change this, but since the stubbornly Scottish-accented Connery was playing a Spanish-Egyptian, it didn’t perhaps matter. The film was a huge hit and Lambert conquered a third sector of the cinema audience.

Now at the height of his fame, Lambert was hanging out with Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in New York, totem of a certain strand of eighties chic that had now become mainstream. Fortunately, he was remarkably capable of handling what his countrymen dubbed ‘Lambert mania’. With the same insouciance he exhibited on screen, he was able to discern the difference between image and reality in the midst of a decade that increasingly confused the two. “There was me, Christophe, and the other Christophe, the movie star who was worshipped,” he told a French magazine much later. “Between ‘action’ and ‘cut’, I’m another guy.” That said, he married within the profession — to another star of the era, Diane Lane, in 1998 — and consistently paired up with fellow actors. From 2007 he was with Sophie Marceau, and is currently with Italian Camilla Ferranti.

No matter how down to earth he remained, he couldn’t have expected his fall to come every bit as fast as his ascent. He recently claimed he could see it coming when he went to buy a paper and “saw my mug on 70 magazine covers… The public had had it up to here with Christophe Lambert.” But his lead in Michael Cimino’s The Sicilian in 1987 was slammed, influential U.S. critic Gene Siskel comparing his acting to “a member of the walking dead”. From then on he couldn’t seem to do anything right. It was as if, as the nineties retreated into the security of nostalgia, he reminded everyone just too much of the hubris and novelty of the decade gone by. The arrival of a universally loathed Highlander sequel in 1991, to which he was contractually tied, didn’t help, and a succession of thrillers failed to convince. Then 1995’s Mortal Kombat attached him in the public consciousness to a series of vaguely camp, rather downmarket fantasy and sci-fi flicks. He was working but it was not work worthy of a man who had defined an era.

Pleasingly, however much the more malevolent critics wished it, the joke has never been on him. By the first decade of the 21st century, Lambert was alternating cash-rich comic-book movies such as Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance with arthouse fare like Claire Denis’ White Material, where he starred alongside Isabelle Huppert, and the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! In the meantime, he’d also built a career as a producer, beginning with the 1994 French comedy Neuf Mois and its Hugh Grant-starring American remake, Nine Months. There were also two novels, a mineral water business and, perfectly Gallicly, partnership in a vineyard producing his own wine, Les Garrigues de Beaumard-Lambert.

He remains perfectly at ease with his past. While for many who lived it the eighties is still viewed through a filter of shame, to generations since its unselfconscious extravagance seems like the last time Europe was looking forward. Christophe Lambert is able to enjoy his part in it, so perhaps he wasn’t shortsighted after all.

This article originally appeared in Issue 63 of The Rake.