Charged Affairs

The diplomat’s art is shrouded in mystery, and, it would appear, plenty of extracurricular shenanigans. Originally published in Issue 51 of The Rake, Nick Scott taps into the wayward practices of ambassadorial mischief.

Henry Wotton, a diplomat and statesman who sat in the House of Commons in the early 17th century, asserted: “An ambassador is an honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country.” But take a close look at the antics of those whose vocational calling is to represent their nations in foreign climes and you’ll find plenty of men and women who dabble in far more iniquitous deeds than a spot of tactical fibbing. While archaeologists from Cairo University stumbled across the 3,100-year-old tomb of Paser, the world’s first royal emissary to foreign nations, diplomacy is not, by some stretch, the oldest profession in the world, yet the moral code by which it seems to be governed is not a million miles away from that overseeing the profession that famously is.

The legions of global viewers of Downton Abbey were alerted to diplomacy’s shady underbelly a few years ago, when its writer, Julian Fellowes, revealed that Kemal Pamuk — the Turkish house guest who panted and puffed his ecstatic farewell to the world during a steamy bout between the sheets with Lady Mary — was based on a real-life Turkish diplomat about whose exploits Fellowes learned when he was shown the diary of one of the protagonists. Readers of the famously understated New York Post, in 2011, were given a far more hyperbolic awakening to the fruity realities of ambassadorial endeavour with a piece that bemoaned official foreign visitors — “egotistical scum unfit to lick one’s shoe; people who have no respect for decent American values” — apparently getting away with all sorts of misdemeanours before hiding behind diplomatic immunity. (“The decadent. The depraved. The malodorous, greedy, drunk and demented,” began one pugnaciously punctuated passage. “They are scofflaws and alleged rapists. Petty criminals... ”)

Like concupiscent students driven to rabid libidinal release by being away from home, ambassadors and envoys the world over seem to get caught up in salacious real-life monkeyshines that give all-new resonance to the expression ‘chargé d’affaires’. The Russian city of Yekaterinburg was confronted with this reality in 2009, when a British deputy consul was forced to resign after being secretly filmed having sex with two prostitutes. In the same year in the same country, Russian media thought they’d died and gone to heaven when video clips were released claiming to show Brendan Kyle Hatcher — an American diplomat whose job was to liaise with religious and human rights groups in the country — contacting three prostitutes and then allegedly being filmed with one of them on a bed in a darkened hotel room. (Hatcher denied any encounter with a prostitute to his superiors at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, CNN reported at the time, and State Department officials said Hatcher had been the victim of a smear campaign.) Not long after, further to the east, 10 current and former South Korean diplomats were disciplined at the country’s consulate in Shanghai, China, in connection with a sex scandal involving a Chinese woman (after her husband, understandably enough, put in a rather peeved tip-off).

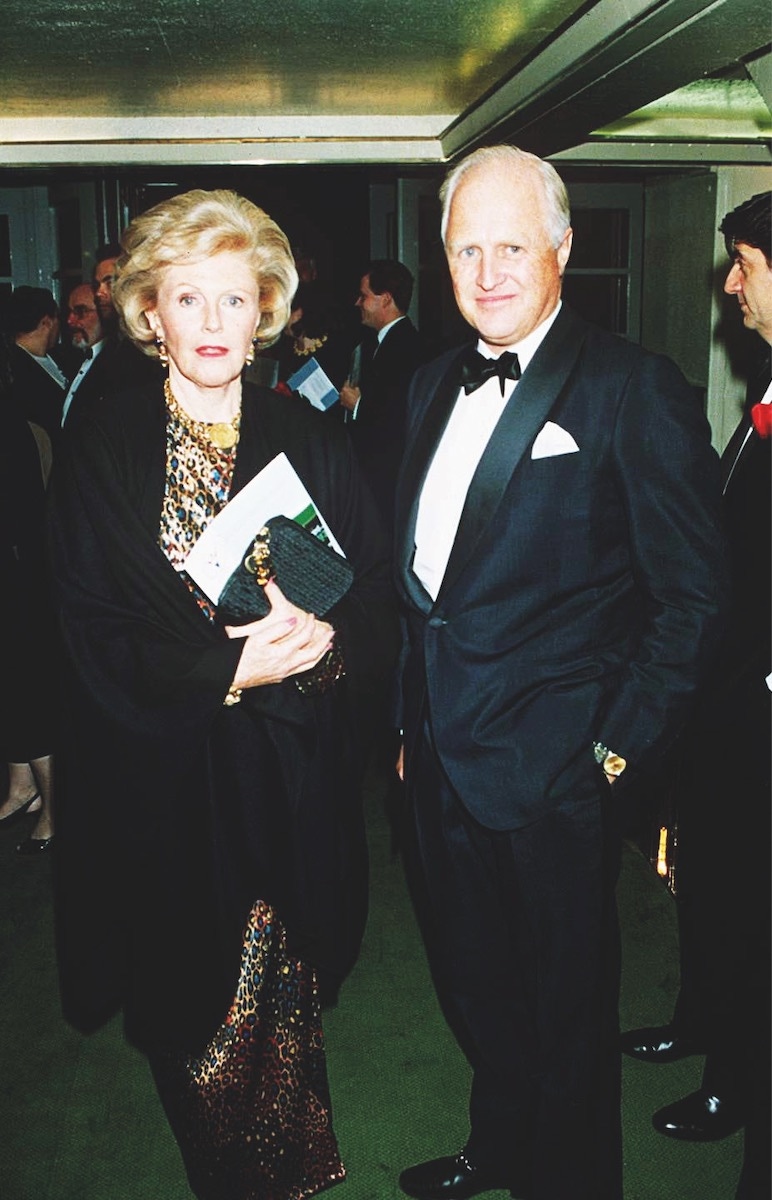

Meanwhile, never assume that ambassadorial horseplay is only a man’s game: in 2015, a bestselling British tabloid ran the beautifully convoluted headline ‘Top British diplomat in Bali had sleazy phone sex with suspected drugs kingpin of a cocaine smuggling plot that put Gloucestershire grandmother on death row’, about the alleged actions of a married female British consul. (The fact that such a headline barely raised the eyebrows of casual observers who had nipped out for some milk is proof, as if it were needed, that we’re dealing here with a less than squeaky-clean profession.)And then, of course, we should ponder the life and times of Pamela Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman, the late, British-born U.S. ambassador to France and leading figure in the Democratic Party. It is rumoured that, as a 12-year-old girl, Harriman was horseriding in Dorset when, having vaulted over the phallus of the nearby Cerne Abbas Giant hill figure, she exclaimed, “God, it’s big!” As to whether the incident turned out to be portentous, it’s telling that the chapter headings of Christopher Ogden’s Life of the Party, an unauthorised biography, are all men’s Christian names.

Harriman’s legendary love life — or, at least, that on record — commenced at the age of 19, when she went on a blind date with Winston Churchill’s son, Randolph, during which she accepted a marriage proposal. Within a couple of years, while living at 10 Downing Street as her young husband was away fighting in the war, she would embark on an affair with an American railway heir 29 years her senior, followed by liaisons with U.S. ambassador Jock Whitney, broadcasting magnate William S. Paley (who called her the courtesan of the century), journalist Edward R. Murrow, and two senior allied generals (Frederick L. Anderson and Sir Charles Portal) before she and Churchill divorced in 1946. Entanglements with legions of wealthy, powerful men ensued — Gianni Agnelli, Aly Khan, Baron Élie de Rothschild, Stavros Niarchos — before she married Leland Hayward, a theatre producer and the chairman of Pacific Airways, in 1960. She also managed to squeeze in a fling with Frank Sinatra before getting hitched to her third and final husband, her former lover and a senior Democrat — and, indeed, diplomat — W. Averell Harriman.

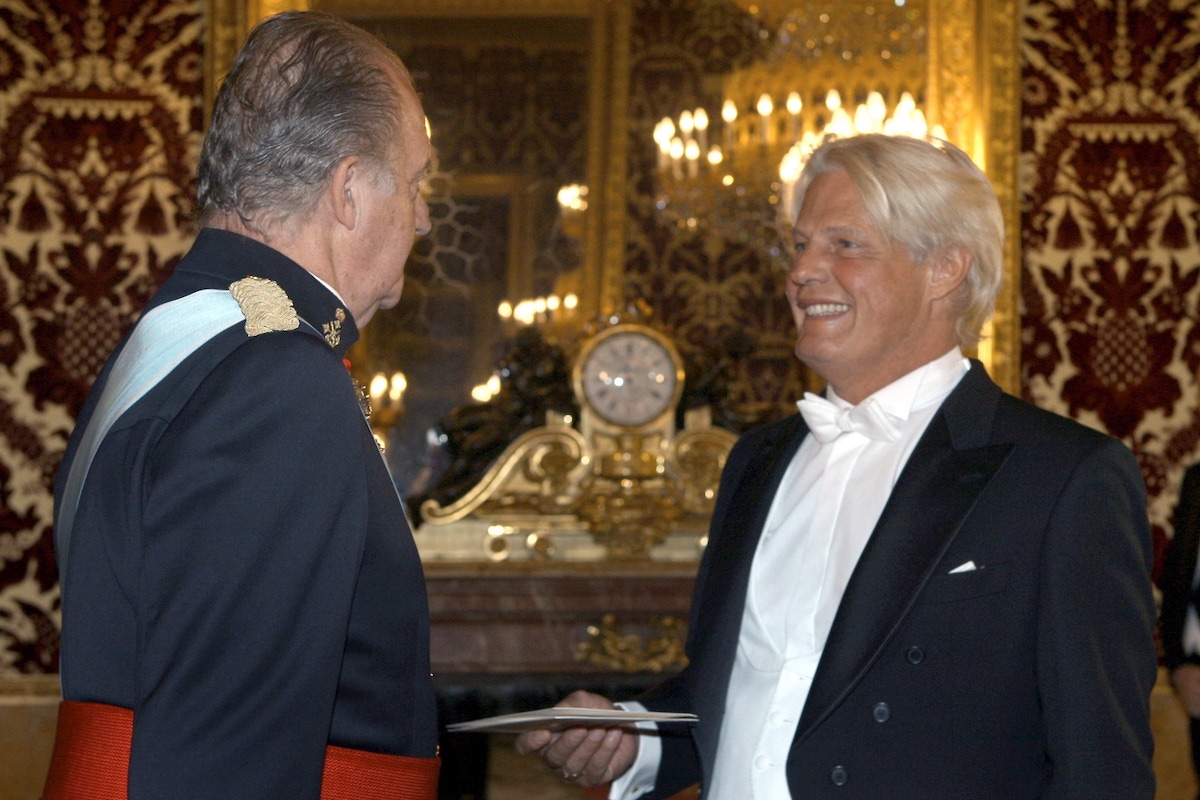

Of course, an ambassador’s foible isn’t necessarily sex-related. John W. Ashe, a veteran diplomat from Antigua who served as president of the United Nations General Assembly from September 2013 for a year, was, according to United States prosecutors, part of a bribery scheme that involved more than $1 million in payments from mysterious sources in China, connected to business interests such as real estate deals. And what of last year’s damning assessment of France’s diplomatic service — the third largest in the world after the U.S. and China, and a source of pride and reverence since the Renaissance — in investigative reporter Vincent Jauvert’s exhaustive book The Hidden Face of the Quai d’Orsay? One case the book details is that of Bruno Delaye, the raffishly dressed friend to the stars who was reported to have taken €91,000 in rent for the use of his Madrid residence by luxury companies between 2008 and 2011, never informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and was the subject of an anonymous tip-off. Another case included a consul general in Hong Kong being turfed out by the Chinese authorities for purloining pricey bottles of wine from clubs and restaurants. There was even a case of France’s National Assembly being advised to help keep a dictator in power in the wake of the Arab spring, the adviser in question having just spent a Christmas break with the leader in question, and alarming claims about the Quai’s opaque budget.

Indeed, even when diplomats’ amorous instincts go into overdrive, the results are not always of a scandalous nature (as demonstrated by Iranian diplomat Ardeshir Zahedi’s mid-1970s dalliance with Elizabeth Taylor, in the former’s native land, which was later described by Vanity Fair as “an artistic and personal adventure”). But when sex is on the menu, it tends to be a dish served spicy. In 2012 — the year of the Diamond Jubilee, incidentally — a warts-and-all book, The Butler Did It, claimed that Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India and Prince Charles’s great uncle, took part in homosexual sex orgies during the war with Scottish butler Roy Fontaine, also known as Archie Hall. Participants at these orgies allegedly included the playwright Terence Rattigan and Austrian-born radio comedian Vic Oliver (Winston Churchill’s son-in-law).

If that’s not a piquant enough rumour, let’s turn to the rich narrative that was the life of Fontaine. A charming, urbane cove as a young man, he passed himself off both as an Arab sheikh and a Texan billionaire as part of his endeavours as a jewel thief, and once tried to sell a pilfered briefcase full of government secrets to the Russians. According to one theory, Fontaine received a lenient sentence for one misdemeanour by threatening to reveal sex secrets about the Heath government. Not a bad charge sheet, but the most heinous was still to come: later in life, he murdered five people, including former cabinet minister Sir Walter Scott-Elliot. Fontaine’s part in earning the former British naval officer and first governor-general of independent India the rather puerile nickname ‘Mountbottom’ (the pun-rich nature of the word ‘viceroy’ also drew regular bouts of mirth) would seem to be easily the most trivial of his transgressions.

By all accounts, assuming such shenanigans did occur in Mountbatten’s colonial pile in New Delhi, it was in the full knowledge of his wife, the Vicereine, Countess Mountbatten of Burma. The couple, who married in 1922, were lavishly rich (her grandfather was the magnate Sir Ernest Cassel, and left her £2 million when she was still in her twenties), and after their wedding the open nature of their relationship apparently became common knowledge, and it was widely held in high society that Lady Mountbatten enjoyed several affairs. But it was her relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru — independent India’s first prime minister — that had the stuffy remnants of the British Raj muttering in unison with the high caste Indian establishment. And it was perhaps a woman having a major influence — that perhaps of clandestine éminence grise — over Indian affairs, rather than any moral dubiousness of infidelity, that got tongues wagging. The nature of Nehru and Edwina Mountbatten’s relationship remains a subject of speculation in India, the Mountbattens’ daughter Pamela’s assertion that her parents and Nehru made “a happy threesome” possibly prompting more lurid gossip than before.

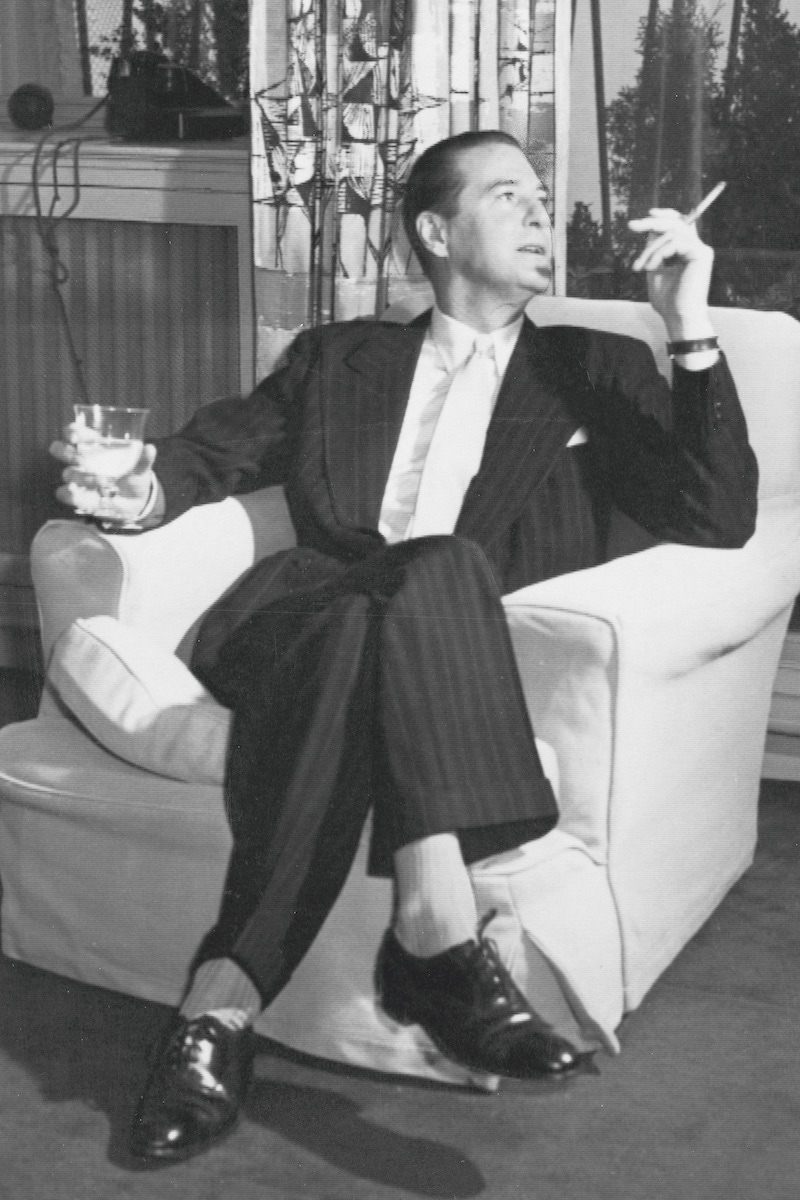

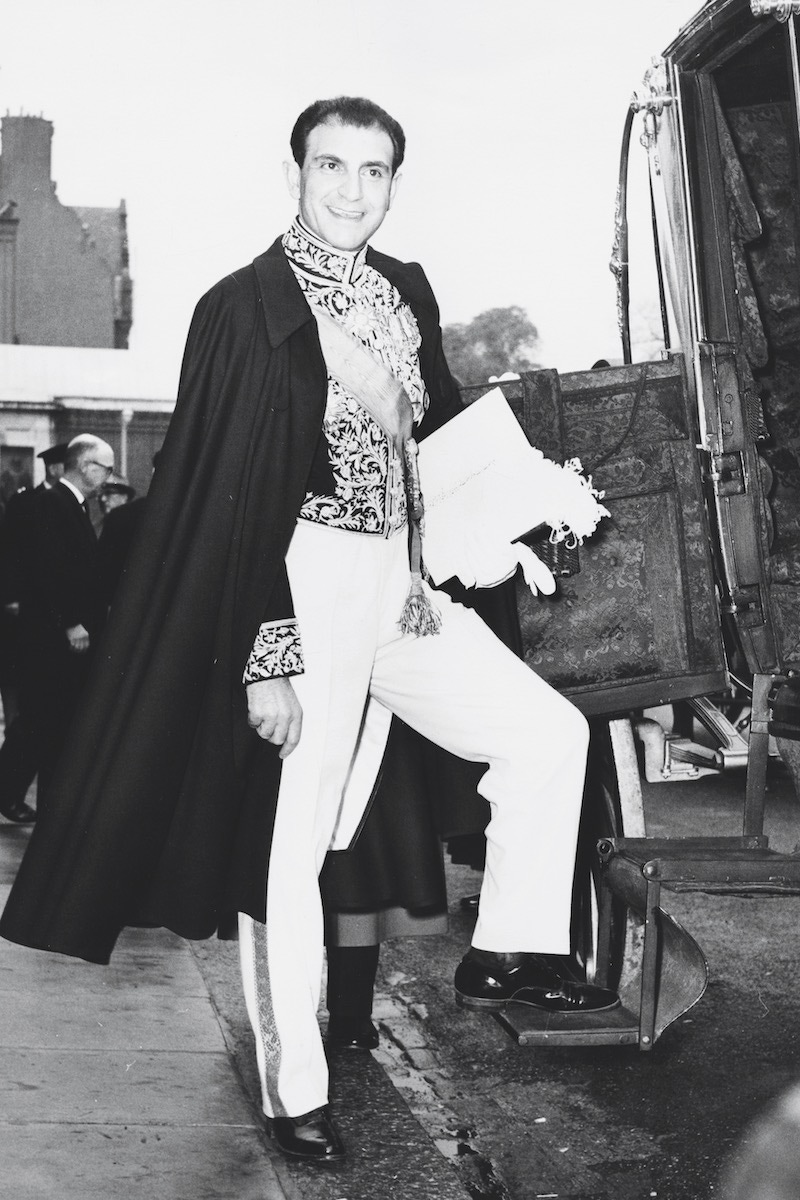

Of course, any discourse on the subject of salacious activities by the world’s prominent diplomatic figures would have a gaping void in it without a close look at the life and lovers of Dominican diplomat Porfirio Rubirosa. The man referred to simply as Rubi by those closest to him was not, on paper, the greatest catch on the postwar jet-set scene. He worked for a dictator of an obscure Caribbean republic (whose pretty young daughter, whom he’d met when she was 17, became his first wife), was just 1.77m tall and distinctly middle class, and was apparently prone to violent jealousy. So what made women (totalling in the four figures), including the world’s richest heiresses, queens, countesses and legendary beauties such as Ava Gardner, Jayne Mansfield, Eva Perón and Zsa Zsa Gabor, compete to get between the Egyptian cotton with him? He wasn’t even consistently flush, like most of the men with whom he rubbed shoulders (one money-making plan involved selling Dominican visas to Jews wishing to flee Nazi persecution; another ruse involved a jeweller who had fled civil-war Spain asking Rubi to retrieve his store’s stock — the Dominican returned from Madrid with $180,000 worth of stock missing from the inventory, and an unlikely story about being robbed by snipers). So what was Rubi’s appeal?

There’s a clue in one of his many nicknames, ‘Toujours Prêt’, or Always Ready. The nickname is given further poetic resonance when considered in tandem with the fact that the staff and clientele in smart Parisian restaurants at one point began calling huge pepper mills ‘Rubirosas’, and not because the legendary playboy had any predilection for dried-spice seasonings. Truman Capote (and how he knew is anyone’s guess) described Rubi’s member in an unfinished novel, Answered Prayers, as an “eleven-inch café-au-lait sinker as thick as a man’s wrist”.

While the legend of an appendage that could remove plaster from walls would not have harmed his strike rate, Rubi’s lifestyle would also have dazzled. Thought to be the inspiration behind the romantic hero of Harold Robbins’s pulp-fiction potboiler The Adventurers, Rubi played polo, flew B-25 bombers and raced Ferraris at Le Mans. A man whose synapses sizzled with derring-do, he even, in the summer of 1952, reacted to a tip-off about sunken treasure off the coast of the Dominican Republic by assembling a makeshift expedition of men, many of whom, within a week of arrival, were arrested for drunken behaviour before making a dash for the treasure, only to be hit by a storm that caused $250,000 worth in damage to the vessel.

Perhaps even more than his adventure-book heroics, women were mesmerised by his charisma. Spectator columnist Taki Theodoracopulos has it that when Rubi had sunk a few, he would produce a guitar and sing, “I’m just a gigolo”, but he was also a gent of the first order. “If he was talking to an 80-year-old or a four-year-old, the most beautiful woman in the world could walk in and he wouldn’t look at her,” recalls a friend, Mildred Ricart, whose husband was a Foreign Service colleague of Rubi’s. “He made each woman feel that she was the most important thing in the world. There are a lot of men who are excellent in bed, but you can’t go to dinner with them.” In short, he had a ‘je ne sais quoi’, which, bottled, would have solved his sporadic money troubles several times over.

Rubirosa died aged 56 a stone’s throw from two of his favourite haunts — the Longchamp racecourse and the Bagatelle Polo Club — when his Ferrari hit a curb on the Allée de la Reine Marguerite in the Bois de Boulogne and then struck a tree at high speed. It was a terrible tragedy, of course, but — outside rock ’n roll circles — has a bowing-out ever been more suited to how a person lived? And, of course, it’s not only the legend that lives on: the threads that made up Rubi’s narrative tapestry are no doubt still being woven into X-rated scenes, all around the world, by the members of a profession that somehow manages to be both cloaked in secrecy and soaked in scandal.

This article originally appeared in Issue 51 of The Rake.