Clash of The Tartans

Supposedly, tartan is best kept in certain families, but the fashion industry has other ideas on the matter. Originally featured in Issue 37 of The Rake by current Editor Tom Chamberlin he looks into how in the world of menswear, the options and availability have flung wide open.

When our illustrious Founder first tasked me with writing this story, the subsequent rush of jingoism — part anxiety, part faux-patriotism (I’m not Scottish) — was a bizarre sensation. My spirit rallied, and a vision of me fully laden in Celtic garb — kilt, sporran, sheathed claymore and holding aloft my wee sharpened stag-antler Sgian Dubh in last-stand, Braveheart defiance — became somewhat alluring. Humankind impulsively rallies to flags and emblems. The cultural zeal they pollinate dictates their longevity. Yet, who’d have thought that a cloth pattern would do the job for so long?

During the course of human history, the cut of one’s jib has been the most effective means by which we human folk judge, identify and categorise ourselves and other people. Take, for example, the toga: we know that the Romans wore them. Fast forward to today, in any student town, should you see people with their bedsheets draped over the body in an Etruscan manner, you will think, ‘Oh, it’s a toga party’. Hussars wore a pelisse off the shoulder. The Bloods and the Crips sport red and blue respectively, as do Manchester United and Manchester City football clubs, another two parties with an ongoing blood feud, this side of the Atlantic. The Ghostbusters don jumpsuits and the New Zealand All Blacks wear, well…

None of these, however, have the resonance, the blood-summoning potency, the flash, the dash and the statement that are borne by tartan (plaid to our American cousins). Tartan is a statement of sovereignty, of kinship, of rebellion, and now, it seems, of fashion. Tartan has entered the style zeitgeist, with tartan making a cameo in the collections of celebrated maisons.

Bespoke has its idiosyncrasies, contingent as it is on the preferences of a specific client. It is only from a high-street perspective where things get more interesting. For ready-to-wear, tartan will carry a rationale and a story from the designers who have decided to incorporate it into their collections, and who believe that, ultimately, people are interested in wearing it. Acase in point is the tartan-patterned jacket in the autumn/winter ’14 Goodwood collection from British behemoth Belstaff.

Duke of Windsor 'Wearing the Balmoral Tartan' in 1936. (Photo courtesy of Alamy).

Duke of Windsor 'Wearing the Balmoral Tartan' in 1936. (Photo courtesy of Alamy).

Duke of Windsor 'Wearing the Balmoral Tartan' in 1936. (Photo courtesy of Alamy).

Duke of Windsor 'Wearing the Balmoral Tartan' in 1936. (Photo courtesy of Alamy).

Outerwear has been an impetus for many of the recent collections in menswear, and for a while now, the Belstaff revival — the vroom-vroom adventure-luxury aesthetic of a brand repatriated — has been at the vanguard of this. The commandeering of Goodwood to give it grounding and direction adds some lifeblood to the designs, especially with a recent tartan number. The home of the Festival of Speed is also home to the Earl of March and Kinrara, heir to four duchies, one of which is the Duchy of Gordon in the county of Inverness. The Gordon tartan has a subtle, patina-ish effect on the jacket, making it look like it had once been proud and bright, but several thousand miles on the road have worn it down to an understated, pusillanimous tone. And I don’t mean this pejoratively. Belstaff’s Vice President of Design, Frederik Dyhr, has fashioned a nuanced design: the parched brass buttons, army smock-like skirt and thinned collar, and the perfect dark green and blue hue of the tartan blending gracefully into the classic design of the Trialmaster jacket. You find yourself entranced by the subtle tonality and elegant new palette added to the usually monochrome jackets. “We deliberately wanted to create a design language which was linked to Goodwood,” he says. “The Gordon tartan is a great vehicle to unite the world of Goodwood with the world of Belstaff.” Dyhr describes the aesthetic oeuvre of tartan itself as “instantly recognisable”. “It’s branding without a label or logo”, which is the crux of the argument and a simple justification for its usage.

Pitching in as expected, employing his shtick of doing British style better than the British, is Ralph Lauren. The Black Watch tartan three-piece suit from his upcoming Purple Label collection is the brand at its absolute best. With a sweeping double-breasted waistcoat that gives it just the right degree of formality, it is certainly one of the contenders for this season’s (and the foreseeable future’s) defining rakish suit.

As for the political history of tartan in fashion, we turn to our MVP for these sorts of nuggets: The Rake’s Fashion History Editor, James Sherwood. “At its most visceral level, tartan speaks about patriotism, loyalty and fighting for a cause,” he says. “Perhaps this was its appeal for the punk movement in the ’70s.” Further evidence that the punk era is pretty much dead: Johnny Rotten recently said, “I never preached anarchy, it was just a novelty in a song.” Sherwood goes on to say, “I don’t see any punk spirit in the resurgence of tartan for autumn/winter ’14. Neither does tartan tailoring reflect any social commentary on the recent Scottish Independence vote, which is a pity, because British fashion was rabidly political in the ’70s and ’80s. What we’ve seen in recent seasons is an appetite for colour and texture in tailoring cloth that tartan takes to a natural extreme. In the language of clothes, tartan still speaks with a gruff, heroic brogue, so it delivers pattern without prettiness or femininity.”

So just what is this iconic pattern? Well, first and foremost, it isn’t Scottish. Don’t get me wrong — as with the thistle, the Scots have the current cultural custodianship of it, but it isn’t actually Scottish. In fact, the practice of the weave dates back several thousand years, as far away from Scotland as western China.

As for the age-old question of the difference between tartan and check, well, tartan is woven in a conventional ‘2/2 twill’, meaning that the warp and weft are woven at right angles to one another. The weft is woven under two warp threads, and then over two warp threads — hence the term ‘2/2’. The result is a diagonal stepped pattern, and a tough, smooth cloth that quite naturally.

With tartan cloth, thanks to the relatively loose weave and the use of bold, contrasting coloured yarns, the twill forms visible diagonal lines where different colours cross. This gives the unique appearance of new tones blended from the individual yarns, which is what distinguishes a tartan from an ordinary check. Each complete repeat of the tartan’s pattern is called a ‘sett’.

Tartans are also frequently made with brushed yarns to add a light nap and to soften the handle. Most commonly in the case of tartan, the yarns themselves are combed before being woven, rather than the cloth being brushed as a stage in the finishing process. Essentially, it has always been a means of identification.

Regrettably, it also befalls on me to bust the romance of tartan being the representative colours of ancient and noble clans — they weren’t. The Scottish Tartans Museum states that, “By the end of the 18th century, large-scale commercial weavers had taken up the production of tartan. At first they assigned numbers to identify the patterns, but soon began to give them names. These included not only names of Highland clans, but also town names. The names were not meant to be representative in any way — they were there as a sales tool, to identify one tartan pattern from another. In the early 19th century, the idea began to gel that the names borne by the tartans represented actual connections to these clans.”

So we have all, I am afraid, been the victims of a scam of Wolf-of-Wall-Street-meets-Bernard-Madoff-Ponzi-scheme proportions. In 1815, the Highland Society of London wrote to the clan chiefs, asking them to submit samples of their clan tartans. Many had no idea what this was. Apparently, a lot of clansmen simply chose something arbitrary or wrote to tartan manufacturers to choose something they liked.

Nevertheless, the royals picked it up and ran with it as only they could: Queen Victoria made one her own, and the tradition filtered down through the aristocracy from there. If you happen to be reading this as a subject of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II: firstly, lucky you; secondly, you have a tartan. You are entitled to wear the tartan of your chief, the aforementioned Queen, and this is the Royal Stewart tartan. This now brings us in a rather nice circle back to fashion — from Queen to McQueen, if you will.

Prince Charles wearing tartan at Balmoral Castle.

Alexander McQueen was one of two of the most prominent names who incorporated tartan into their eponymous brands; the other being, of course, Vivienne Westwood. Both designers were self-proclaimed rebels from the median of fashion, destabilising what was familiar and changing it to something that was more visceral, entertaining and au courant. You could argue that McQueen’s break away from his Savile Row training to his trailblazing approach to his creations — which ended up in a posthumous return to Savile Row — was the greatest achievement in menswear since Tommy Nutter rewrote the rulebook on traditional tailoring.

His emblematical tartan is very similar to the Royal Stewart, using as it does a blood-red base with green and yellow weaving. It was exhibited admirably by the doyen of dandyism, Vogue’s International Editor-at-Large Hamish Bowles, who sported a tartan cape and suit from McQueen’s autumn/winter 2006 collection at the Met Gala — soon after the designer’s sudden death. Westwood, too, took her fondness for Scottish textiles and employed it for her punk-fashion mien. “I am English, so it is impossible for me to ignore British culture in my designs. The fabrics I use are often traditional British fabrics — English flannel and barathea wool, Irish linen, Scottish tartan. These fabrics benefit from classic British manufacturing techniques, as represented by the Savile Row tradition,” says Dame Vivienne.

Poetically she adds, “Harris tweed and tartan are as indispensable as a lion would be to a painter of the animals in paradise. Tartan looks great with more tartan, along with every other material from velvet to lace and metal. It tells a heroic tale of crags and glens, mists and locks, and sea and the sun on the heather. The Scottish mills that weave, enhance and develop traditional fabrics are among the most exciting and versatile factories in the world, and wonderful to work with.” If you take a look at this season’s Morning Glory suit, it is a faultless example of Westwood’s virtuoso ability to find order in chaos. It features a proud purple and red tartan on the arms and side panels, a new lighter purple and faded scarlet tartan weave on the foreparts that merge into the patch pockets, and then straight down to match the trouser, so it all tunes together beautifully. The combination of the avant-garde and traditionalism is both contemporary and relevant to the sartorially absorbed.

Prince Charles wearing tartan at Balmoral Castle.

Alexander McQueen was one of two of the most prominent names who incorporated tartan into their eponymous brands; the other being, of course, Vivienne Westwood. Both designers were self-proclaimed rebels from the median of fashion, destabilising what was familiar and changing it to something that was more visceral, entertaining and au courant. You could argue that McQueen’s break away from his Savile Row training to his trailblazing approach to his creations — which ended up in a posthumous return to Savile Row — was the greatest achievement in menswear since Tommy Nutter rewrote the rulebook on traditional tailoring.

His emblematical tartan is very similar to the Royal Stewart, using as it does a blood-red base with green and yellow weaving. It was exhibited admirably by the doyen of dandyism, Vogue’s International Editor-at-Large Hamish Bowles, who sported a tartan cape and suit from McQueen’s autumn/winter 2006 collection at the Met Gala — soon after the designer’s sudden death. Westwood, too, took her fondness for Scottish textiles and employed it for her punk-fashion mien. “I am English, so it is impossible for me to ignore British culture in my designs. The fabrics I use are often traditional British fabrics — English flannel and barathea wool, Irish linen, Scottish tartan. These fabrics benefit from classic British manufacturing techniques, as represented by the Savile Row tradition,” says Dame Vivienne.

Poetically she adds, “Harris tweed and tartan are as indispensable as a lion would be to a painter of the animals in paradise. Tartan looks great with more tartan, along with every other material from velvet to lace and metal. It tells a heroic tale of crags and glens, mists and locks, and sea and the sun on the heather. The Scottish mills that weave, enhance and develop traditional fabrics are among the most exciting and versatile factories in the world, and wonderful to work with.” If you take a look at this season’s Morning Glory suit, it is a faultless example of Westwood’s virtuoso ability to find order in chaos. It features a proud purple and red tartan on the arms and side panels, a new lighter purple and faded scarlet tartan weave on the foreparts that merge into the patch pockets, and then straight down to match the trouser, so it all tunes together beautifully. The combination of the avant-garde and traditionalism is both contemporary and relevant to the sartorially absorbed.

Blue and brown Modern Douglas tartan cashmere single-breasted sport coat, Kiton (available at Uomo Collezioni); brown cashmere single-breasted waistcoat, navy wool spotted wool tie, navy wool pocket square with white trim, and brown and leather belt, all Brunello Cucinelli; grey and brown wool-cashmere trousers, Ermenegildo Zegna Couture; brown Sartorial leather loafers, Tod's. Grey cotton shirt with wide-spread contrast collar, Charvet (property of The Rake).

Blue and brown Modern Douglas tartan cashmere single-breasted sport coat, Kiton (available at Uomo Collezioni); brown cashmere single-breasted waistcoat, navy wool spotted wool tie, navy wool pocket square with white trim, and brown and leather belt, all Brunello Cucinelli; grey and brown wool-cashmere trousers, Ermenegildo Zegna Couture; brown Sartorial leather loafers, Tod's. Grey cotton shirt with wide-spread contrast collar, Charvet (property of The Rake).

Prince Charles wearing tartan at Balmoral Castle.

Alexander McQueen was one of two of the most prominent names who incorporated tartan into their eponymous brands; the other being, of course, Vivienne Westwood. Both designers were self-proclaimed rebels from the median of fashion, destabilising what was familiar and changing it to something that was more visceral, entertaining and au courant. You could argue that McQueen’s break away from his Savile Row training to his trailblazing approach to his creations — which ended up in a posthumous return to Savile Row — was the greatest achievement in menswear since Tommy Nutter rewrote the rulebook on traditional tailoring.

His emblematical tartan is very similar to the Royal Stewart, using as it does a blood-red base with green and yellow weaving. It was exhibited admirably by the doyen of dandyism, Vogue’s International Editor-at-Large Hamish Bowles, who sported a tartan cape and suit from McQueen’s autumn/winter 2006 collection at the Met Gala — soon after the designer’s sudden death. Westwood, too, took her fondness for Scottish textiles and employed it for her punk-fashion mien. “I am English, so it is impossible for me to ignore British culture in my designs. The fabrics I use are often traditional British fabrics — English flannel and barathea wool, Irish linen, Scottish tartan. These fabrics benefit from classic British manufacturing techniques, as represented by the Savile Row tradition,” says Dame Vivienne.

Poetically she adds, “Harris tweed and tartan are as indispensable as a lion would be to a painter of the animals in paradise. Tartan looks great with more tartan, along with every other material from velvet to lace and metal. It tells a heroic tale of crags and glens, mists and locks, and sea and the sun on the heather. The Scottish mills that weave, enhance and develop traditional fabrics are among the most exciting and versatile factories in the world, and wonderful to work with.” If you take a look at this season’s Morning Glory suit, it is a faultless example of Westwood’s virtuoso ability to find order in chaos. It features a proud purple and red tartan on the arms and side panels, a new lighter purple and faded scarlet tartan weave on the foreparts that merge into the patch pockets, and then straight down to match the trouser, so it all tunes together beautifully. The combination of the avant-garde and traditionalism is both contemporary and relevant to the sartorially absorbed.

Prince Charles wearing tartan at Balmoral Castle.

Alexander McQueen was one of two of the most prominent names who incorporated tartan into their eponymous brands; the other being, of course, Vivienne Westwood. Both designers were self-proclaimed rebels from the median of fashion, destabilising what was familiar and changing it to something that was more visceral, entertaining and au courant. You could argue that McQueen’s break away from his Savile Row training to his trailblazing approach to his creations — which ended up in a posthumous return to Savile Row — was the greatest achievement in menswear since Tommy Nutter rewrote the rulebook on traditional tailoring.

His emblematical tartan is very similar to the Royal Stewart, using as it does a blood-red base with green and yellow weaving. It was exhibited admirably by the doyen of dandyism, Vogue’s International Editor-at-Large Hamish Bowles, who sported a tartan cape and suit from McQueen’s autumn/winter 2006 collection at the Met Gala — soon after the designer’s sudden death. Westwood, too, took her fondness for Scottish textiles and employed it for her punk-fashion mien. “I am English, so it is impossible for me to ignore British culture in my designs. The fabrics I use are often traditional British fabrics — English flannel and barathea wool, Irish linen, Scottish tartan. These fabrics benefit from classic British manufacturing techniques, as represented by the Savile Row tradition,” says Dame Vivienne.

Poetically she adds, “Harris tweed and tartan are as indispensable as a lion would be to a painter of the animals in paradise. Tartan looks great with more tartan, along with every other material from velvet to lace and metal. It tells a heroic tale of crags and glens, mists and locks, and sea and the sun on the heather. The Scottish mills that weave, enhance and develop traditional fabrics are among the most exciting and versatile factories in the world, and wonderful to work with.” If you take a look at this season’s Morning Glory suit, it is a faultless example of Westwood’s virtuoso ability to find order in chaos. It features a proud purple and red tartan on the arms and side panels, a new lighter purple and faded scarlet tartan weave on the foreparts that merge into the patch pockets, and then straight down to match the trouser, so it all tunes together beautifully. The combination of the avant-garde and traditionalism is both contemporary and relevant to the sartorially absorbed.

Blue and brown Modern Douglas tartan cashmere single-breasted sport coat, Kiton (available at Uomo Collezioni); brown cashmere single-breasted waistcoat, navy wool spotted wool tie, navy wool pocket square with white trim, and brown and leather belt, all Brunello Cucinelli; grey and brown wool-cashmere trousers, Ermenegildo Zegna Couture; brown Sartorial leather loafers, Tod's. Grey cotton shirt with wide-spread contrast collar, Charvet (property of The Rake).

Blue and brown Modern Douglas tartan cashmere single-breasted sport coat, Kiton (available at Uomo Collezioni); brown cashmere single-breasted waistcoat, navy wool spotted wool tie, navy wool pocket square with white trim, and brown and leather belt, all Brunello Cucinelli; grey and brown wool-cashmere trousers, Ermenegildo Zegna Couture; brown Sartorial leather loafers, Tod's. Grey cotton shirt with wide-spread contrast collar, Charvet (property of The Rake).

It is not hard to draw a link between the roguish, outlandish, rebellious and mutinous behaviour with which tartan was associated during England and Scotland’s quarrelsome history, and see what these two geniuses were thinking when taking tartan and formulating it as their own symbol of disobedience. The notion of the princess of the punk movement and her prodigy protégé both using tartan to such great effect, is one of the finest fashion faits accomplis since the Duke of Wellington decided his Hessian boots needed a redesign for muddier fields.

All this talk of pugnaciousness and sticking it to the man may give the impression that there are no traditional high-street options available to the conformists and formal eccentrics out there. But, fear not: there are more than just heavy waxed-cotton jackets available. Oliver Spencer, the eponym of the modern men’s clothing label, is also the creative mind behind the more classical men’s brand Favourbrook. He was pretty concise when explaining how tartan could be summed up: “Fun. Colour. Attitude. Punk. Dance. Wearing tartan is about having fun and kicking up a little bit. At Favourbrook, we embrace colour, and tartan trousers are very colourful.” “Kicking it up a little bit” is exactly what he has done, and the inclusion of tartan trousers in the mix was all the more credit to him, as the trousers are a blend of foible and primness. Add a velvet smoking jacket, G.J. Cleverley black-tie pumps, an Emma Willis dress shirt and a bow-tie, and you have a rakish black-tie outfit right there.

Subtly entering the fray is Dunhill with their sophisticated tartan three-piece suit. The design of the suit itself — notch lapel and regular flap pockets — is classically cut, as if to sit back on the details to let the tartan do the talking, which is what it does best. Dunhill has always observed a reverence for the traditions of the brand and British designs, and this suit is a representation of the tremendously exciting future for Dunhill, with John Ray at the helm.

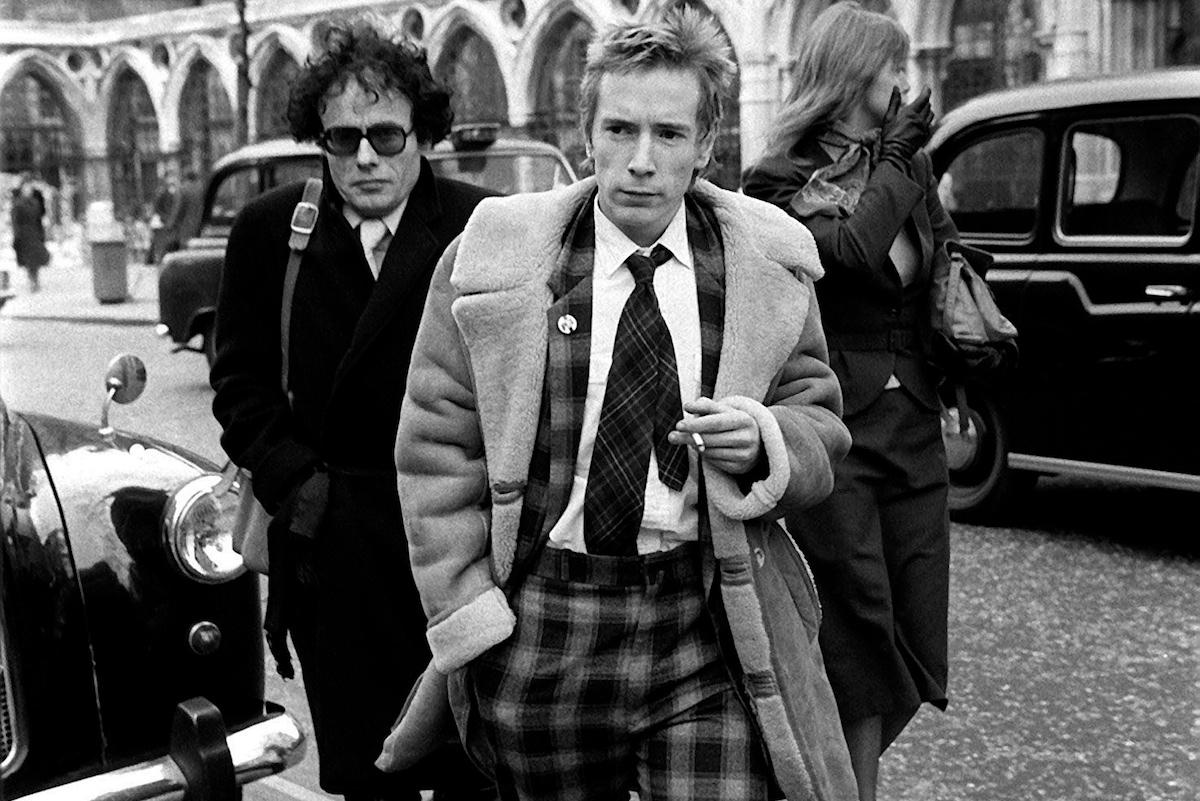

John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols attends court in 1979 wearing a bold tartan suit, clashing tie and shearling overcoat.

Well inside their comfort zone is the denizens of Hackett, who have produced a Black Watch smoking jacket all bedecked in frogging to give a distinctly Scottish military look. The fainthearted ought not try this: it is a bold piece of “kit”, as Jeremy Hackett likes to refer to his creations in customary understatement. The cords and patterns of the frogging give the tartan a whole new lease of life. In fact, in this jacket, the tartan becomes a supporting act. That being said, employing Black Watch tartan — by far the most accessible of tartans on the mainstream market — is a shrewd tactic.

If you’re looking for more evidence, try the frequent outings of Marc Jacobs in a kilt. There is provenance in his designs involving tartan, though not all of them particularly successful. He was fired from Perry Ellis in 1993 when his ‘grunge’ didn’t quite become the talk of the town. He started wearing kilts after asking his assistant to buy a pair of “funny pants” from Barneys, and the assistant returned with a Comme des Garçons kilt. Since then, his hirsute legs are often seen poking out from underneath the hem of a tartan kilt. Jean Paul Gaultier is still, after all these years, showcasing tartans, such as the tablecloth-white, gold, red and black pattern in his autumn/winter ’14 collection in Paris Fashion Week earlier this year. This was a Britannia-inspired punk-rock look that was straight out of the Vivienne Westwood instruction manual — and it looked fantastic. Chic but dangerous all at once.

To be frank, the revival in tartan seems to be a calling card in the renaissance of men’s fashion. It signals the about-turn from Charles Tyrwhitt, Suitsupply, Reiss and Topman, and is an indication that men care about garments of longevity, of provenance and of eccentricity. For a long time now, tartan has been overlooked as a stuffy niche of the old aristocracy, and whilst in part that is certainly true, it’s nice to see them still proudly sporting their colours (however erroneous this notion is, as pointed out earlier). The thrust of the movement into tartan is a tryst between functioning flâneurs and daring designers, the result of which The Rake is hugely proud and to watch develop. Maybe now that the secret is out, the mills in Scotland can create a special tartan for The Rake, and you shall henceforth see Wei Koh, and myself fully clad in our clan colours.

This article originally appeared in Issue 37 of The Rake.

John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols attends court in 1979 wearing a bold tartan suit, clashing tie and shearling overcoat.

Well inside their comfort zone is the denizens of Hackett, who have produced a Black Watch smoking jacket all bedecked in frogging to give a distinctly Scottish military look. The fainthearted ought not try this: it is a bold piece of “kit”, as Jeremy Hackett likes to refer to his creations in customary understatement. The cords and patterns of the frogging give the tartan a whole new lease of life. In fact, in this jacket, the tartan becomes a supporting act. That being said, employing Black Watch tartan — by far the most accessible of tartans on the mainstream market — is a shrewd tactic.

If you’re looking for more evidence, try the frequent outings of Marc Jacobs in a kilt. There is provenance in his designs involving tartan, though not all of them particularly successful. He was fired from Perry Ellis in 1993 when his ‘grunge’ didn’t quite become the talk of the town. He started wearing kilts after asking his assistant to buy a pair of “funny pants” from Barneys, and the assistant returned with a Comme des Garçons kilt. Since then, his hirsute legs are often seen poking out from underneath the hem of a tartan kilt. Jean Paul Gaultier is still, after all these years, showcasing tartans, such as the tablecloth-white, gold, red and black pattern in his autumn/winter ’14 collection in Paris Fashion Week earlier this year. This was a Britannia-inspired punk-rock look that was straight out of the Vivienne Westwood instruction manual — and it looked fantastic. Chic but dangerous all at once.

To be frank, the revival in tartan seems to be a calling card in the renaissance of men’s fashion. It signals the about-turn from Charles Tyrwhitt, Suitsupply, Reiss and Topman, and is an indication that men care about garments of longevity, of provenance and of eccentricity. For a long time now, tartan has been overlooked as a stuffy niche of the old aristocracy, and whilst in part that is certainly true, it’s nice to see them still proudly sporting their colours (however erroneous this notion is, as pointed out earlier). The thrust of the movement into tartan is a tryst between functioning flâneurs and daring designers, the result of which The Rake is hugely proud and to watch develop. Maybe now that the secret is out, the mills in Scotland can create a special tartan for The Rake, and you shall henceforth see Wei Koh, and myself fully clad in our clan colours.

This article originally appeared in Issue 37 of The Rake.

John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols attends court in 1979 wearing a bold tartan suit, clashing tie and shearling overcoat.

Well inside their comfort zone is the denizens of Hackett, who have produced a Black Watch smoking jacket all bedecked in frogging to give a distinctly Scottish military look. The fainthearted ought not try this: it is a bold piece of “kit”, as Jeremy Hackett likes to refer to his creations in customary understatement. The cords and patterns of the frogging give the tartan a whole new lease of life. In fact, in this jacket, the tartan becomes a supporting act. That being said, employing Black Watch tartan — by far the most accessible of tartans on the mainstream market — is a shrewd tactic.

If you’re looking for more evidence, try the frequent outings of Marc Jacobs in a kilt. There is provenance in his designs involving tartan, though not all of them particularly successful. He was fired from Perry Ellis in 1993 when his ‘grunge’ didn’t quite become the talk of the town. He started wearing kilts after asking his assistant to buy a pair of “funny pants” from Barneys, and the assistant returned with a Comme des Garçons kilt. Since then, his hirsute legs are often seen poking out from underneath the hem of a tartan kilt. Jean Paul Gaultier is still, after all these years, showcasing tartans, such as the tablecloth-white, gold, red and black pattern in his autumn/winter ’14 collection in Paris Fashion Week earlier this year. This was a Britannia-inspired punk-rock look that was straight out of the Vivienne Westwood instruction manual — and it looked fantastic. Chic but dangerous all at once.

To be frank, the revival in tartan seems to be a calling card in the renaissance of men’s fashion. It signals the about-turn from Charles Tyrwhitt, Suitsupply, Reiss and Topman, and is an indication that men care about garments of longevity, of provenance and of eccentricity. For a long time now, tartan has been overlooked as a stuffy niche of the old aristocracy, and whilst in part that is certainly true, it’s nice to see them still proudly sporting their colours (however erroneous this notion is, as pointed out earlier). The thrust of the movement into tartan is a tryst between functioning flâneurs and daring designers, the result of which The Rake is hugely proud and to watch develop. Maybe now that the secret is out, the mills in Scotland can create a special tartan for The Rake, and you shall henceforth see Wei Koh, and myself fully clad in our clan colours.

This article originally appeared in Issue 37 of The Rake.

John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols attends court in 1979 wearing a bold tartan suit, clashing tie and shearling overcoat.

Well inside their comfort zone is the denizens of Hackett, who have produced a Black Watch smoking jacket all bedecked in frogging to give a distinctly Scottish military look. The fainthearted ought not try this: it is a bold piece of “kit”, as Jeremy Hackett likes to refer to his creations in customary understatement. The cords and patterns of the frogging give the tartan a whole new lease of life. In fact, in this jacket, the tartan becomes a supporting act. That being said, employing Black Watch tartan — by far the most accessible of tartans on the mainstream market — is a shrewd tactic.

If you’re looking for more evidence, try the frequent outings of Marc Jacobs in a kilt. There is provenance in his designs involving tartan, though not all of them particularly successful. He was fired from Perry Ellis in 1993 when his ‘grunge’ didn’t quite become the talk of the town. He started wearing kilts after asking his assistant to buy a pair of “funny pants” from Barneys, and the assistant returned with a Comme des Garçons kilt. Since then, his hirsute legs are often seen poking out from underneath the hem of a tartan kilt. Jean Paul Gaultier is still, after all these years, showcasing tartans, such as the tablecloth-white, gold, red and black pattern in his autumn/winter ’14 collection in Paris Fashion Week earlier this year. This was a Britannia-inspired punk-rock look that was straight out of the Vivienne Westwood instruction manual — and it looked fantastic. Chic but dangerous all at once.

To be frank, the revival in tartan seems to be a calling card in the renaissance of men’s fashion. It signals the about-turn from Charles Tyrwhitt, Suitsupply, Reiss and Topman, and is an indication that men care about garments of longevity, of provenance and of eccentricity. For a long time now, tartan has been overlooked as a stuffy niche of the old aristocracy, and whilst in part that is certainly true, it’s nice to see them still proudly sporting their colours (however erroneous this notion is, as pointed out earlier). The thrust of the movement into tartan is a tryst between functioning flâneurs and daring designers, the result of which The Rake is hugely proud and to watch develop. Maybe now that the secret is out, the mills in Scotland can create a special tartan for The Rake, and you shall henceforth see Wei Koh, and myself fully clad in our clan colours.

This article originally appeared in Issue 37 of The Rake.