American Psycho Analysis

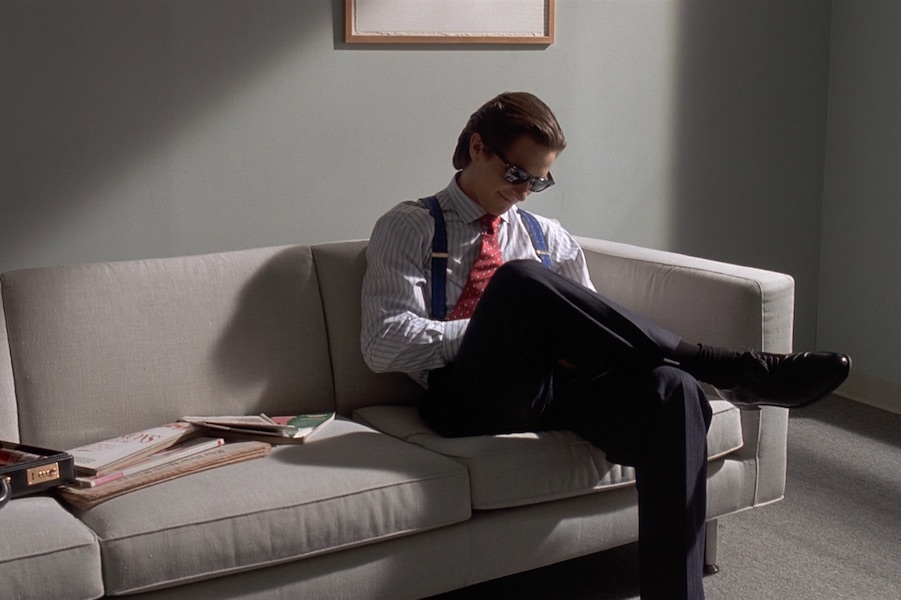

Looking for some rakish Halloween inspiration? Look no further than Bret Easton Ellis’s controversial novel American Psycho, which turned 25 last year but remains as relevant as ever.

Though the tale was intended as a snapshot of the conformist, consumerist, superficial late-1980s cultural landscape, American Psycho’s vision of modern urbane life has proven scarily prescient. Today, the world’s gone just a little bit Patrick Bateman.

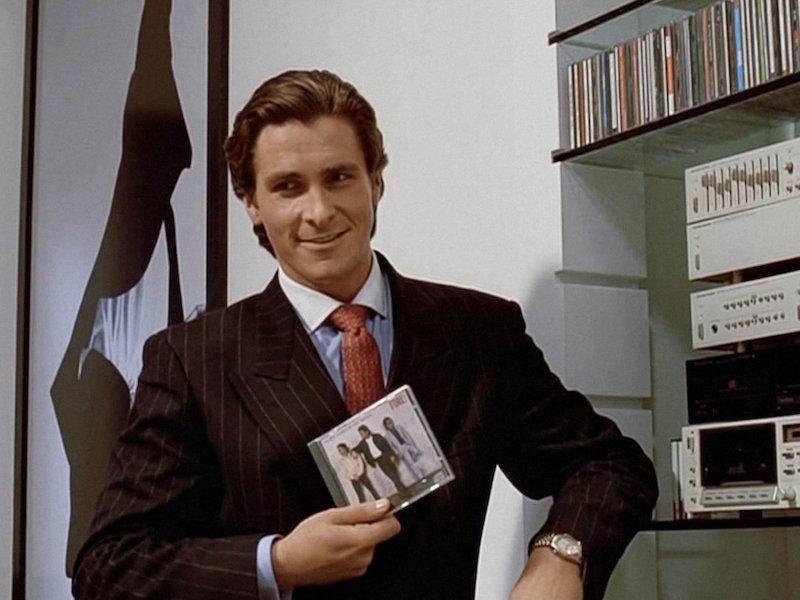

Of that dashing yuppie psychopath, author Bret Easton Ellis said following the book’s release, “it was very clear to me when I started writing that this was going to be a character who was so obsessed with appearances that he was going to tell the reader in minute, numbing detail about everything he owns, everything he wears, everything he eats.” Many of us do much the same today via social media, fixated — like Bateman — with wearing the right thing, getting the hot reservation, eating the haute cuisine, and ensuring our circle is acutely aware of our access to these tasteful status symbols. Facebook et al have made flaunting so much easier than it was in 1991.

This year, marking American Psycho’s quarter-century anniversary, Ellis pondered whether — were he transported to 2016 — the sociopathic Bateman would be fiercely engaged with social media. “Would he have a Twitter account bragging about his accomplishments? Would he be using Instagram, showcasing his wealth, his abs, his potential victims? Possibly. There was the possibility to hide during Patrick’s ’80s reign that there simply isn’t now; we live in a fully exhibitionistic culture… The idea of Patrick’s obsession with himself, with his likes and dislikes and his detailing — curating — everything he owns, wears, eats, and watches, has certainly reached a new apotheosis. In many ways the text of American Psycho is one man’s ultimate series of selfies.”

Ellis explained that the book “was really about the dandification of the American male.” (A phenomenon the #menswear-obsessed Rake reader may well be familiar with.) “It was really about what is going on with men now, in terms of surface narcissism. Beginning in the ’80s, men were prettifying themselves… they were taking on a lot of the tropes of gay male culture and bringing it into straight male culture — in terms of grooming, looking a certain way, going to the gym, waxing, and being almost the gay porn ideals. You can track that down to the way Calvin Klein advertised underwear, a movie like American Gigolo, the re-emergence of Gentlemen’s Quarterly.”

Indeed, the pages of GQ provided rich source material for the excruciatingly detailed descriptions of designer style found in American Psycho. “GQ was inordinately helpful in costuming the characters in the book. They should have gotten credit,” Ellis said. Researching the characters’ wardrobes was a matter of “looking through GQ and seeing what the guys on Wall Street were wearing, since every other pictorial during those two years had guys hanging out in front of various office buildings downtown.”

The writer — who admits “I don’t like clothes” — said he deliberately combined the garments he saw in magazines in haphazard, mismatched fashion. “What a lot of people don’t realise, and what I had a lot of fun with, is that if you really saw the outfits Patrick Bateman describes, they’d look totally ridiculous. He would describe a certain kind of vest with a pair of pants and certain kind of shirt, and you think, ‘He really must know so much,’ but if you actually saw people dressed like this, they would look like clowns. It was a subtle joke. If you read it on a surface level and know nothing about clothes, you read American Psycho and think, ‘My God, we’re in some sort of princely kingdom where everyone just walked out of GQ.’ No. They look like fools. They look like court jesters, most of them.”

Living in New York while writing the novel, Ellis’s other core form of research involved spending time with the sort of strutting young financial ‘Masters of the Universe’ that form Patrick Bateman’s social set. Initially having no plans to make the protagonist a specialist in Murders & Executions, “the longer I hung out with these guys,” Ellis said, “the more the aspect of the serial killer came into view. I don’t know why; I just suddenly thought, ‘Oh, my God. He’s going to be a serial killer.’” Bateman commits his horrific crimes with utter disregard for humanity, and total impugnity, ending the book (spoiler alert!) unchastened, unpunished, and free to continue enjoying his privileged, luxurious lifestyle. Not so dissimilar to the careless, irresponsible bankers who wreaked havoc on the world economy during the 2008 financial crisis… Which played a major role in precipitating the dandy #menswear revolution Patrick Bateman also acted as a harbinger for.

Repudiating the cult of the sharp-dressed modern-day #gentleman, Ellis explained “American Psycho is a book about becoming the man you feel you have to be, the man who is cool, slick, handsome, effortlessly moving through the world, modeling suits in Esquire, having babes on his arm. It’s about lifestyle being sold as life, a lifestyle that never seemed to include passion, creativity, curiosity, romance, pain. Everything meaningful wiped away in favour of surfaces, in favor of looking good, having money, having six-pack abs, dating the hottest porn star, going to the hottest clubs… I think Fight Club is about this, too — this idea that men are sold a bill of goods about what they have to be in order to feel good about themselves, or feel important. No one can really live up to these ideals, so there’s an immense amount of dissatisfaction roiling through the collective male psyche. Patrick Bateman is the extreme embodiment of that dissatisfaction. Nothing fulfills him. The more he acquires, the emptier he feels.”

Ellis recently wrote that although “moneyed, beautifully attired, impossibly groomed and handsome,” Bateman is also “morally bankrupt, totally isolated and filled with rage, a gorgeously dressed and empty thing, a young and directionless mannequin hoping that someone, anyone, will save him from himself.”

Kinda strikes a chord, right, Rake reader? Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a lunch meeting with Cliff Huxtable at the Four Seasons in 20 minutes. (Check out the #foodporn and #menswear on my Instagram: @christianbbarker).