Contrarian: Joint Effort

“Every child,” Pablo Picasso once said, “is an artist." The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” The answer, says this month’s pub table slapper, is a steady stream of freshly plucked ganja.

For the record, I’m no beanie-wearing dope hound. As a student, I pretended to like smoking joints out of peer-group pressure – an act of quasi-volition that frequently left me prostrate, chewing tufts of underlay and vainly trying to suppress volcanic surges of paranoia whose lava deposits still encrust my psyche to this day. For me, the finger-wagging warnings of Harry Anslinger – the unscrupulous government official who, when the most pitifully unsuccessful booze ban in history ended, whipped America into a frenzy of panic about cannabis in order to give the Department of Prohibition a new raison d’etre – ring true: “If the hideous monster Frankenstein came face to face with marijuana, he would drop dead of fright.”

Weed, spliff, draw – whatever you care to call it - is a massive de-motivator. It’s loaded with carcinogens, and turns lots of sensible people into hood-eyed conspiracy theorists whose limp philosophical spewings utterly trash the notion that tetrahydrocannabinol broadens all minds into which it seeps. (Take the dope-soaked bohemians who spurn modern medicine, for example: people who have been drugged into shunning thousands of years’ worth of peer-reviewed human endeavour in favour of dabbing coconut oil on their shakras are surely among the most pitifully narrow-minded on the planet. There’s a reason it’s called “dope”.)

And yet, for a small, select group of people with vastly more fertile minds than mine, marijuana – whose plant matter, hemp, has been used for centuries to make incense, cloth and rope – is far more useful as a professional aid than any other natural substance on earth. I’m talking, of course, about artists. Not desk-jockey commercial creatives who consider themselves “a bit arty”: real artists – canvas-slashing, self-harming Gallic modernists; eccentric pioneers who changed popular music forever; poets whose muses take them on phantasmagorical journeys to places the rest of us will only visit vicariously, through their work. It is they for whom artistic endeavour and an arduous affair with Mary Jane are so sinuously entwined. And it’s time this reality was sanctified by law.

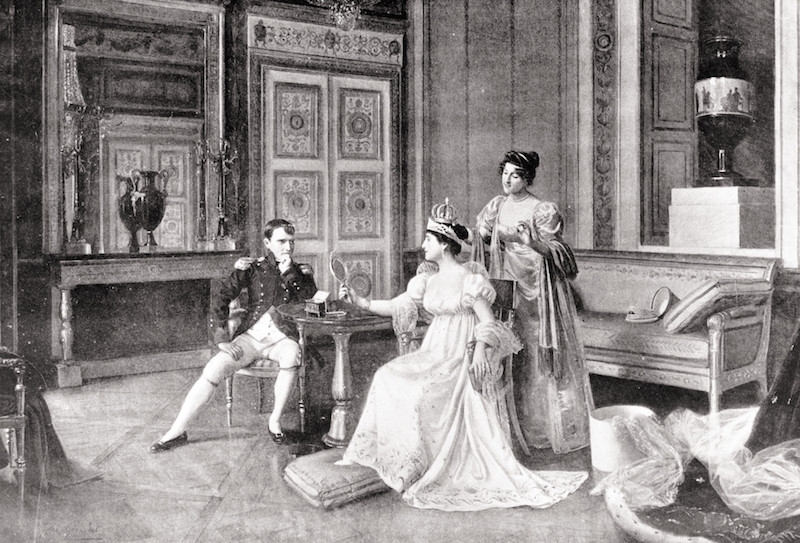

“You know that hashish always evokes magnificent constructions of light, glorious and splendid visions, cascades of liquid gold.”In fact, marijuana should not only be legal for artists – it should be compulsory. Failing to equip our zaniest creative minds with a steady stream of it would be like depriving scientists of a substance that sent their innate inquisitiveness into overdrive. OK, the idea that cannabis stimulates the Dionysian side of the brain sounds like beanbag posturing from someone overly proud of the blim-burns on his LP sleeves: but there have been studies, proper ones, and it all boils down to the way in which dope sends users' “semantic priming” into overdrive. In other words, it’s a cognitive catalyst that allows free-associative streams of consciousness to turn into torrents. Users with an artistic bent have also reported weed’s capacity to silence their inner critic and aid concentration. This latter claim seems implausible – as anyone who’s ever played chess against a stoner will testify – but neuroscience supports the claim: THC binds with cannabinoid receptors in the hippocampus, temporarily colonising that whole zone of your grey matter and interfering – in a positive way, if one is engaged with creative endeavour – with what is and isn't worth remembering at any given time. ”Cannabis is an assassin of referentiality inducing a butterfly effect in thought,” is how Rich Doyle, author of Darwin's Pharmacy (a book which may enrage the young-Earth creationist who has never asked himself, “Why did God make marijuana?”) puts it. “It induces a parataxis wherein sentences resonate together and summon coherence in the bardos between one statement and other, rather than through explicit semantics.” No wonder Alexandre Dumas and Charles Baudelaire hosted parties where fellow members of the creative intelligentsia would get through roughly the amount of hashish that Napoleon’s troops had bought back from India roughly 50 years before. “You know that hashish always evokes magnificent constructions of light, glorious and splendid visions, cascades of liquid gold,” wrote Baudelaire in Artificial Paradises, and Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali and William Shakespeare – yes, traces of it were found in clay pipes excavated from The Bard’s garden in Stratford-Upon-Avon – are all among those who would concur with a slightly dreamy nod. I’m not suggesting that all illicit substances enhance creativity. If there is anyone other than William Burroughs, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lou Reed or David Bowie who has produced works which would have been better without heroin use, then I’ve yet to come across them. Art stimulated by cocaine would be in danger of becoming as bombastically solipsistic as its regular users’ bar-room anecdotes. Ecstasy stupefies its users into enjoying the most artless creative spew ever to be vomited from speaker cones, and seems unlikely ever to inspire anything more soul-enriching than music which sounds like a primate banging a biscuit tin to the squeals of a car alarm. But weed? We need to wake up, acknowledge how conducive the sweet leaf is to artistic endeavour, and get it flowing freely between the synapses and neurons of those whose cerebral fruits prompt us all, collectively, to ponder the human condition. If that’s too much to ask, then we really may as well pour some ochre into the shell of a giant sea snail, and trudge humbly back to the cave wall.