I Drink, Therefore I Can

Alcohol, the abstemious naysayers claim, is a harmful depressant which impairs cerebral faculty. Try telling that, though, to the manifold writers, artists and other luminaries - not to mention a former world leader voted the greatest Briton of all time - who have reached the peak of their powers while knocking back the sauce.

'My tastes are simple,' Winston Churchill once averred. 'I am easily satisfied with the best.' He certainly bore this out when it came to alcohol, where the best - Hine brandy, Pol Roger champagne, Johnnie Walker Red Label scotch - was constantly on tap. Churchill's appetite for a tipple was prodigious by anyone's - and would be regarded as ruinously reckless by today's - standards. Tony Blair's confession in his memoirs that he used alcohol as a 'prop' to cope with pressure in his time as prime minister was hailed as an audaciously candid admission, but Churchill would have speared him on his cocktail stick and dunked him in one of the famous wartime martinis he was wont to consume, along with the scotches, champagnes, brandies and highballs, while directing operations against the Nazis. 'I drink champagne at all meals, and buckets of claret and soda in between,' he attested, with only minimal exaggeration; but unlike, say, Herbert Asquith, the Liberal premier during World War I who was often observed swaying and slurring at the dispatch box, and acquired the nickname 'Squiffy' rather than fog it. 'Always remember,' he enjoined in his memoir The World Crisis, 'that I have taken more out of alcohol than it has taken out of me.'

Many looked upon that statement as an addict's wilful blindness, but a fair number of the greatest writers, painters and musicians have also been assiduous in getting their rounds in, keen to exemplify Arthur Rimbaud's dictum that 'The Poet makes himself a seer by a long, gigantic and rational derangement of all the senses' (if not to go the whole lock-in hog with Charles Baudelaire's more hardcore 'be drunk always'). William Faulkner claimed not to be able to face a blank page without a bottle of Jack Daniels to hand, and, many tumblers later, had filled his A4 sheets with portions of future Penguin Modern Classics like As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury. Beethoven fell heavily under the influence in the later - and many would say the greater - part of his creative life. It's hard to divorce Jackson Pollock's compulsive drips, Francis Bacon's bodily contortions or Vincent van Gogh's pulsating cornfields from the scotch - and absinthe - fuelled maelstrom of their creation. And then there's American painter Robert Rauschenberg, who typically drank a bottle-and-a-half of Jack Daniels a day over the course of a long and phenomenally productive life (83 years, at least 6,000 artworks). At one time, he checked himself into the Betty Ford Center; following his stay, a writer visited his studio to find him partly through his revised daily intake of a bottle of white wine and several vodka and sodas.

'One of the things they teach you at Betty Ford is, 'Don't ever be without something to drink,'' explained Rauschenberg to The New Yorker's Calvin Tomkins. The writer demurred. Surely the draught(s) in question should be non-alcoholic? 'That's what she means!' he laughed.

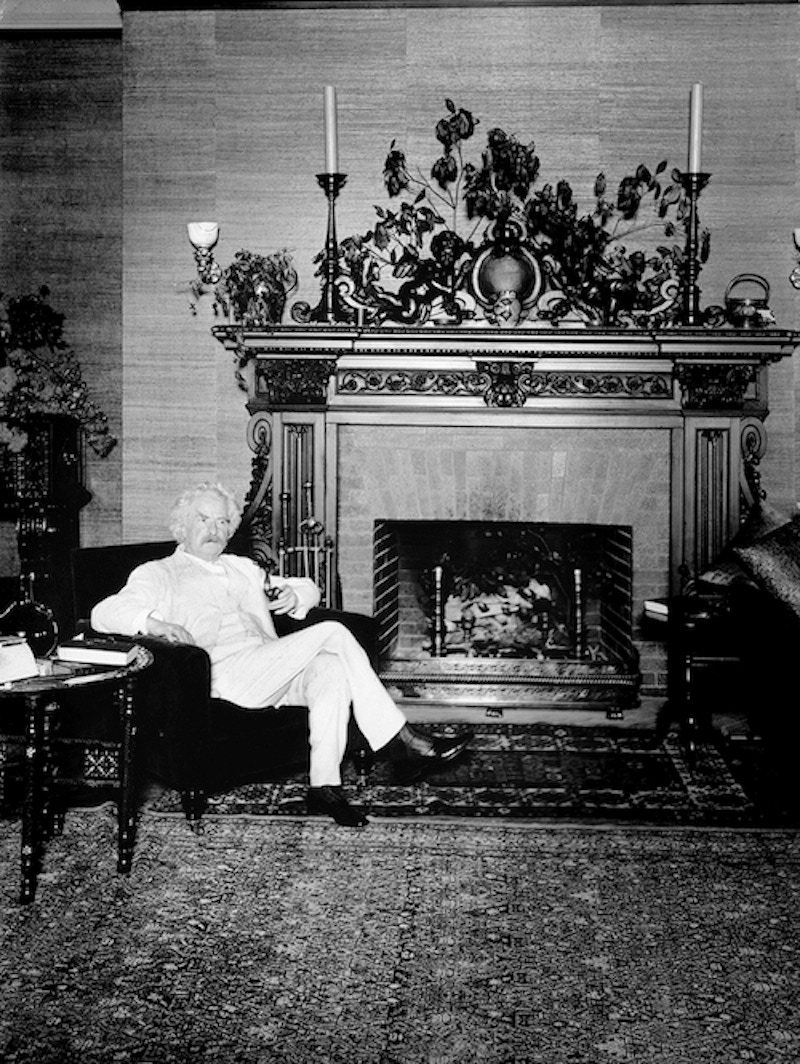

Such thriving in the face of seemingly toxic adversity has led to speculation that a 'Churchill gene' may allow some people to remain focused and creative despite a unit consumption level that would seriously stymie the vast majority. Mark Twain believed it - 'My vices protect me, but they would assassinate you!' - and now science seems to have vindicated the brigade of booze-aliers. A 2004 study at the University of Colorado found that around 15 percent of Caucasians have a genetic variant - the G-variant, as in G-spot - that makes ethanol behave more like an opioid drug, such as morphine, with a stronger-than-normal effect on mood and behaviour. Alcohol was injected directly into the subjects' bloodstreams, and those with the G-variant reported stronger feelings of happiness and elation, with the euphoria followed by a state of relaxation lasting several hours, during which their creative processes blossomed.

On a less exalted plane, a study from the University of Illinois earlier this year suggested that alcohol's buzz could also improve problem-solving skills by enhancing what scientists call our 'working memory capacity' - the ability to remember one thing while thinking about something else - encouraging lateral-thinking strategies and left-field solutions. Test subjects with a blood-alcohol content of 0.07% (just under legally drunk in most US states) perhaps unsurprisingly struggled with attention-intensive trials, but excelled at questions that required more flexible thinking (what word links 'blue', 'cottage' and 'Swiss', for example - the answer being 'cheese', although 'porn' might have got you extra left-field points), solving 40-percent more posers than their stone-cold control group, and three-and-a-half seconds faster to boot. This everything's-going-my-way phase of buzzy inebriation has variously been christened the 'Ballmer Peak' (named for Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, who allegedly discovered that a few nips wondrously enhanced his programming abilities) and the 'Slingshot Effect'.

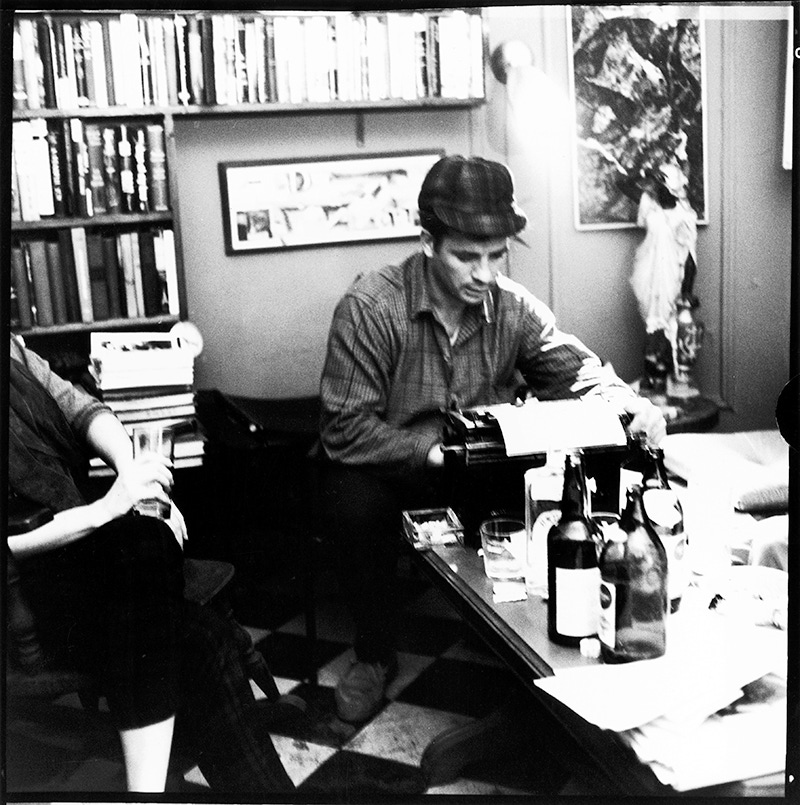

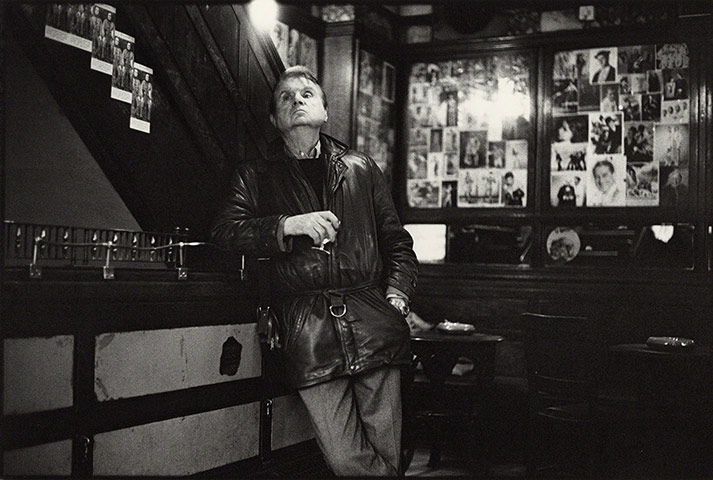

There are some in the Churchill/Rauschenberg camp whose G-variant seems capacious to the point where, as William James said of drunkenness in The Varieties of Religious Experience, no less, 'It is... the great exciter of the Yes function in man.' Look at Hunter S. Thompson, starting his days on the campaign trail with a six-pack of Heineken and a bottle of gin, or disposing of 20 double Wild Turkeys in three hours at his first meeting with his New York publishers (on their tab, natch), then sauntering out as if he'd been gently sipping green tea (in fact, he preferred Chivas Regal when driving or relaxing, and Wild Turkey when cranking up the fun or churning out his speed-freak prose). Charles Bukowski, meanwhile, lived 74 years and published over 45 books of poetry and prose, the majority of which were composed under the (very considerable) influence. The poet laureate of alcoholic lowlives noted that, over the years, he'd spilt copious amounts of 'beer, wine, whiskey, vodka and ale' into his IBM Selectric typewriter. He was immortalised by a bleary, mumbling, farting Mickey Rourke in a 1987 movie called, inevitably, Barfly.

So, as William Blake almost said, the road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom - provided you're lucky enough to have a high expression of alcohol dehydrogenase and tolerance of booze-breakdown products such as acetaldehyde. You'll scale the Ballmer Peak; your Churchill gene may enable you to write a masterpiece or save the world from the dark forces arrayed against it while having a seriously jolly time into the bargain. Churchill himself, perhaps for his own wry amusement, once invited a group of Mormons to his countryseat of Chartwell. The chief Mormon observed: 'Mr Churchill, the reason I do not drink is that alcohol combines the kick of the antelope with the bite of the viper.' Churchill, G-variant in the ascendant, replied: 'All my life, I have been searching for a drink like that.'