IN SICKNESS AND IN WEALTH: THE GOLD DIGGER

And that goes for women and men alike. Despite the efforts of the old-boys’ clubs in finance, politics and other establishment professions, women’s earning power is only increasing, and that means the male-female power ratio is changing. In other words, male gold diggers are operating in your area now. You may know one, or be having a relationship with one. A few of them may be con men, like the Swiss investment banker Helg Sgarbi, who seduced BMW heiress and Germany’s richest woman Susanne Klatten and then blackmailed her; or Peter Chan, feng-shui consultant to Nina Wang, once the richest woman in Asia, who claimed to be her sole beneficiary but was found to have forged her signature on the alleged will. A few may be clowns like Alfonso Díez, the 62-year-old toyboy of the 87-year-old Duchess of Alba (current worth somewhere between $800 million and $5 billion); or Frédéric Prinz von Anhalt, the German policeman’s son who had himself adopted by a hereditary princess and then married Zsa Zsa Gabor. But most of them are just men, doing what some men have been doing for centuries.

In days gone by, women didn’t have the power to move their social position: it was granted to them by their fathers or husbands. Now, women are not only more likely to inherit money directly, but they could well be making more money than the men in their social circle. Figures from the UK’s Centre for Work-Life Policy show that the number of women outearning their husbands is now in the millions. This has resulted, quite naturally, in the rise of the trophy husband. Where previously a successful woman felt the need to find a man as successful as herself, now both sexes have begun to adjust to the idea that she can simply choose a man she finds attractive, just as successful men have been doing for centuries. Rather than having the affair with the tennis coach of old clichés, she can marry him. Men of the old school have a problem with this, but most of us have realised that it’s fair enough and that we’re going to have to shape up — literally. Women want someone who looks good on their arm at a social function and who can turn on the charm, and if they’re the ones paying for the new suit (or even the firm abs, courtesy of that nice man in Harley Street), then that’s fine.

"Where previously a successful woman felt the need to find a man as successful as herself, now both sexes have begun to adjust to the idea that she can simply choose a man she finds attractive."

There are plenty of men looking for that kind of position. It beats working for a living, after all. And in many ways, it’s back to business as usual. Our reflex may be to think of the gold digger as a woman, but the boys were in there first. Change it to ‘fortune hunter’ and the whole enterprise becomes instantly more masculine. Literature is full of roguish fortune-hunters, from Petruchio in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew in the 16th century, to Sir Lucius O’Trigger in Sheridan’s The Rivals in the 18th. By the time we get to Jane Austen in the 19th century, the idea of marriage as a business contract is as powerful as George Wickham’s desire for Georgiana Darcy’s £30,000 in Pride and Prejudice. Charles Dickens, too, gave us a parade of fortune hunters. Often they were used to satirical ends, such as the deluded Alfred Lammle in Our Mutual Friend, who secures the hand of Sophronia Akersham, only to find out that she was after his (equally non-existent) fortune herself. But there is also the spirited and undeniably practical defence of the mercenary approach in Barnaby Rudge. “All men are fortune-hunters, are they not?” asks Sir John Chester of his son Edward. “The law, the church, the court, the camp — see how they are all crowded with fortune-hunters, jostling each other in the pursuit… You ARE one; and you would be nothing else, my dear Ned, if you were the greatest courtier, lawyer, legislator, prelate, or merchant, in existence.”

Sir John is only telling young Ned the way of the world. Until all too recently, the wealth of a bride was a consideration that ranked alongside any other factor in her desirability. The ancient concept of the dowry may have evolved into the more euphemistic concept of ‘making a good marriage’, but it endured well into the 20th century. In her new book, The English in Love, historian Claire Langhamer argues that the romantic idealisation of marriage became commonplace only amid the prosperity that came after World War II. “The willingness to marry for love above all else was strongly linked to economic security,” she says. Love is a luxury, in other words — and not such a great basis for wedded bliss, either. Langhamer links it to the rise in divorce rates, adding, “A matrimonial model based upon the transformative power of love carried within it the seeds of its own destruction.”

In a capitalist system, it’s only natural that marriage is prey to market forces like anything else. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the financial centre of the world shifted from Europe to America, the British aristocracy turned fortune hunters almost overnight. As the Industrial Age created previously unimaginable wealth in the new world of America, they were happy to trade in their heritage to keep their palaces running and the wine cellars stocked. Thus was Spencer-Churchill joined with Vanderbilt, Curzon with Leiter. Winston Churchill’s mother, Jennie Jerome, was American; so was Frances, the great-grandmother of Diana, Princess of Wales. The story was the same on the continent, where Alice Heine of New Orleans became first Duchesse of Richelieu, then Princess of Monaco; and Nonie May Stewart Worthington, the Ohio-born widow of America’s ‘Tin King’ William Bateman Leeds, was reborn as Princess Anastasia of Greece and Denmark. The trade may have seemed to be a fair exchange to both parties, but if any gold was being dug, it was by the grand old houses of Europe, and the men.

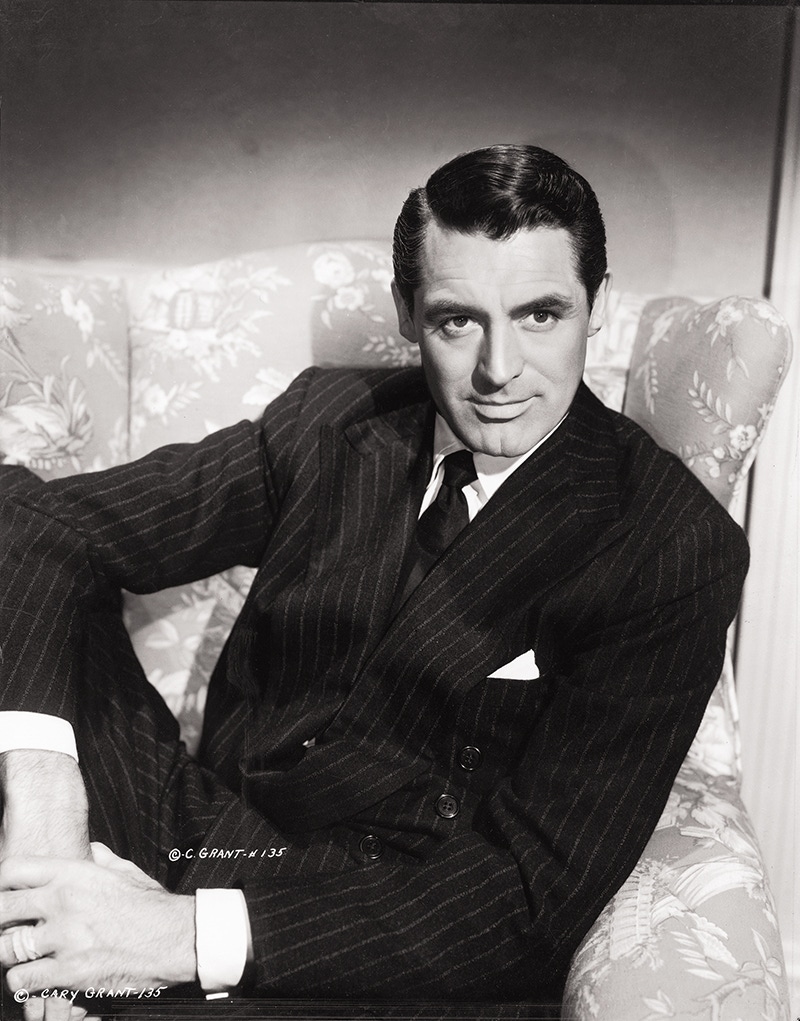

And in this golden age of gold digging, it wasn’t just titles that were being traded. Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton’s seven marriages included three princes, a count and a baron, but her other two husbands were the world’s biggest film star, Cary Grant, and the great playboy Porfirio Rubirosa. Rubirosa, the Dominican polo player, racing driver and occasional diplomat, took up with her just a short while after his divorce from another of America’s richest women, tobacco heiress Doris Duke. Grenada-born bandleader Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson made his way in society as much by using his gift for pleasing well-heeled ladies as by his music, squiring Lady Mountbatten among others.

"Even 20 years later, when Marilyn Monroe went on the hunt for a rich husband in three movies, the world didn’t hesitate a moment before falling in love with her."

Such shady shenanigans were the inspiration for the 1988 film Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, in which two con men, played by Michael Caine and Steve Martin, target a naive American heiress on a French Riviera imbued with 1930s atmosphere. This was itself inspired by the 1964 film Bedtime Story, in which David Niven played the suave Englishman, and Marlon Brando, the American charmer. In both movies, despite their plans for deception, these characters are wholly sympathetic, so firmly set was the idea of the fortune hunter as a lovable rogue. And why not? Even Cary Grant, the world’s sweetheart as well as (briefly) Barbara Hutton’s, could get away with playing the cad marrying for money in Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion in 1941.

When, comparatively recently, the female gold digger came along, she was an even more positive figure. The term may have come from the California Gold Rush of 1848, assigned to the women who waited in bars for miners with something to celebrate, but the women depicted in plays and films, such as the 1933 Gold Diggers of 1933, were heroines — feisty young female Robin Hoods taking back the cash hoarded by the greedy billionaires in the Great Depression of the 1930s. Even 20 years later, when Marilyn Monroe went on the hunt for a rich husband in three movies — Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, How to Marry a Millionaire and Some Like It Hot — the world didn’t hesitate a moment before falling in love with her. After all, it was no more surprising that a girl like her would be after a rich man than it would be that a silly, boorish, old man would be after a girl like her. It’s something for us all to think about — men and women alike.