Why aren’t poets cool any more?

From Ancient Greece to post-War America via 18th Century England, lyrical masters have led intoxicating lives and exuded hip factor from every pore. What happened?

What image does the phrase “modern poet” conjure up in the imagination of the reader? Call me a slave to lazy stereotypes, but for me, none of the character types that glide into view are encumbered by their own charisma. There’s the scruff-pot scholar, all ill-fitting, elbow-patched tweed and non-ironic horn-rims – possibly joined between the lenses by a sticking plaster – who pens Keats-lite odes to nature and death on damp park benches. There’s the pale, bedsit-dwelling pseudo-bard – a far younger species, but with hungrily acquired existential baggage to spare and piles of notepads full of tortured verse documenting unrequited love (“No one was laid”, to borrow from The Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby).

Then there’s the festival-hopping crusty with their confected controversialism (“Woman saying c*nt – that’ll ruffle ‘em”), the would-be mystics who claim to be “just a conduit for” their cod-spiritual otter-shit and the indulgent minimalists who think writing verse in moronbic twonkameter makes them avant-garde. Christ, at least three contemporary odists I’ve heard of only took up verse to badger their exes with plaintive sonnets on social media.

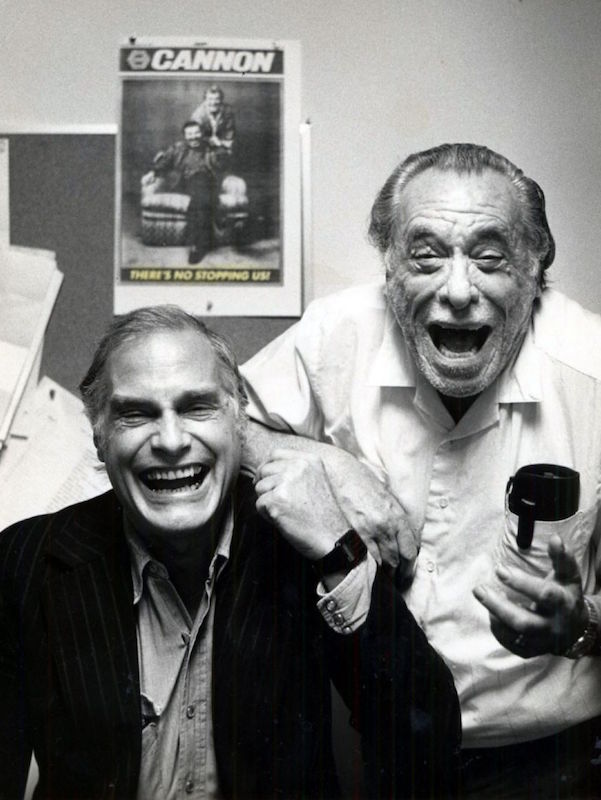

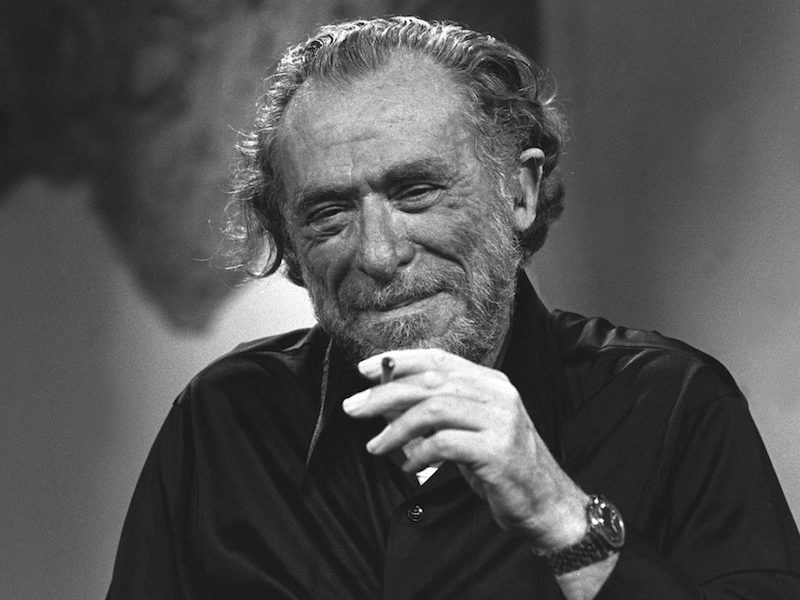

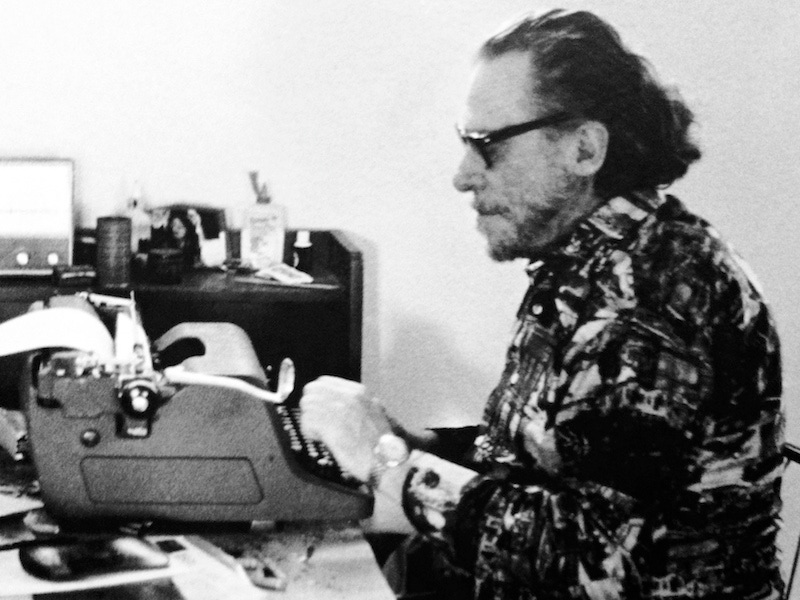

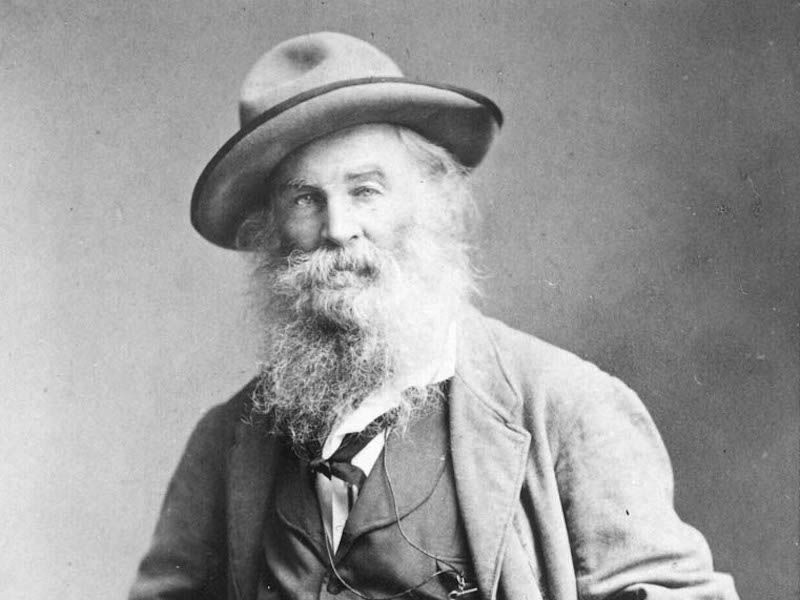

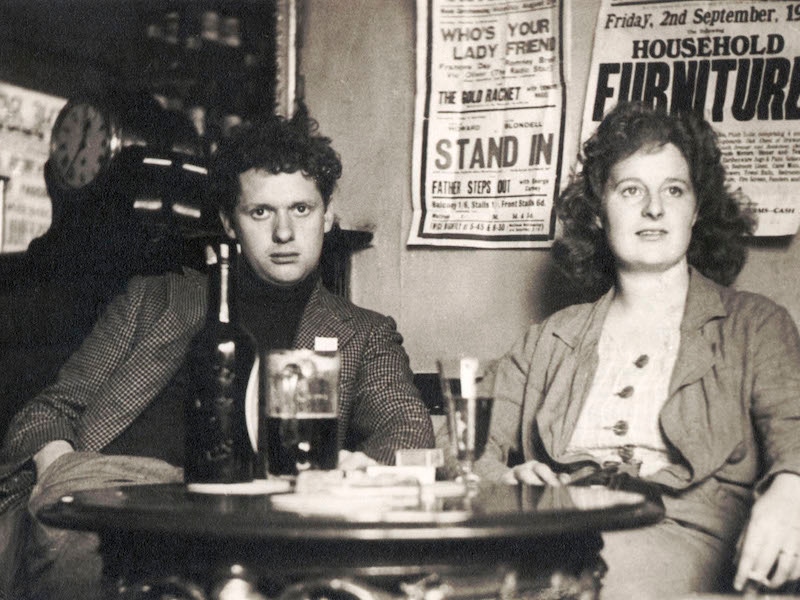

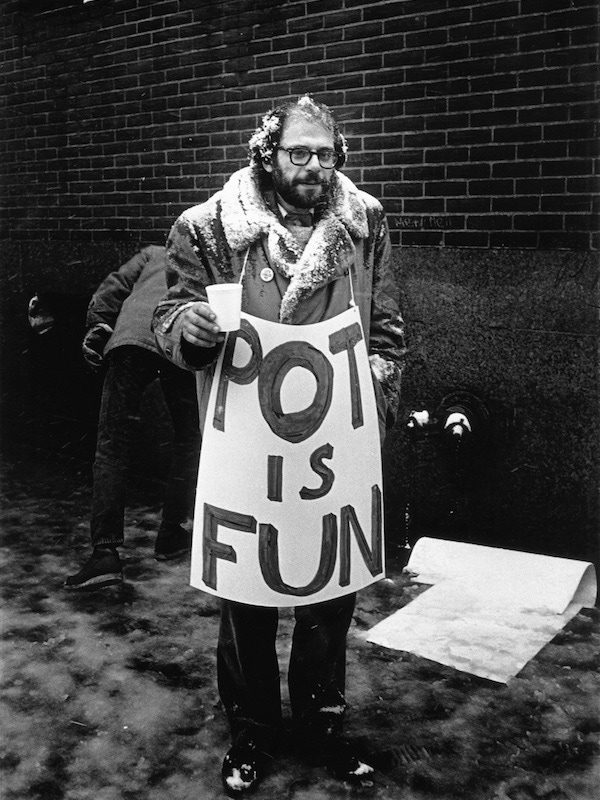

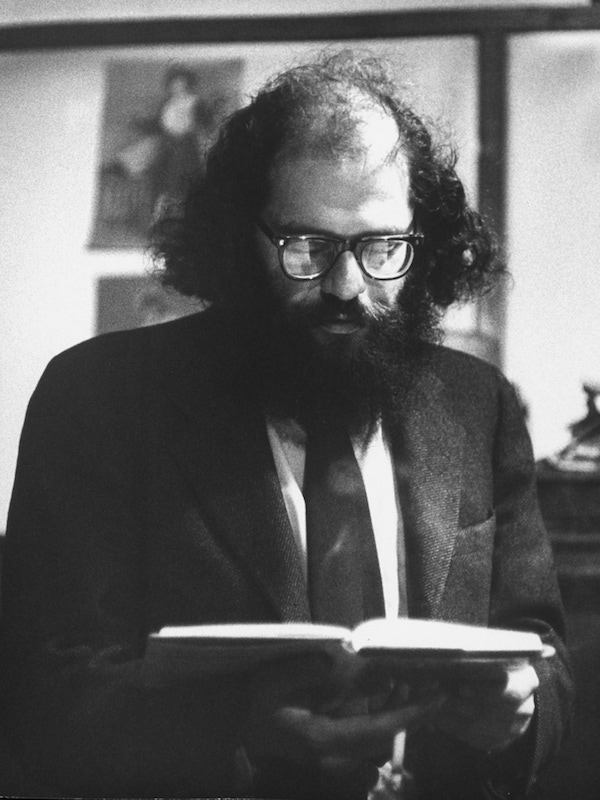

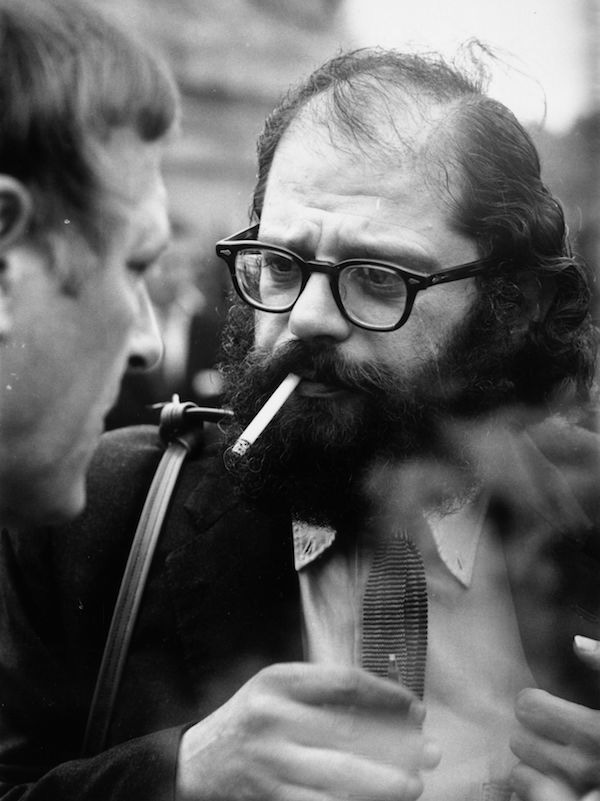

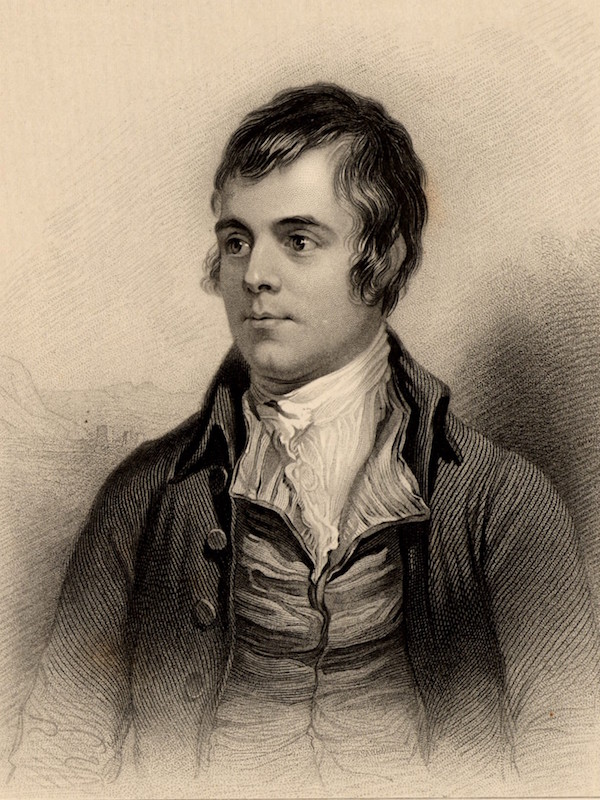

"There’s the pale, bedsit-dwelling pseudo-bard – a far younger species, but with hungrily acquired existential baggage to spare."Now let’s contrast the above with some of the past masters, in reverse chronological order. They didn’t all look the part - t-shirts bearing Allen Ginsberg’s image are never going to be sold in Camden Market - but the troubadours and beat poets who filled up Greenwich Village’s smoky late-night basement dives in the 1960s exuded countercultural cool. Dylan Thomas – who once quipped “An alcoholic is someone you don't like, who drinks as much as you do” – produced his stunning cannon of work so inebriated, he possibly spent much of his writing time with one eye looking at his verse, the other looking for it. So did Charles Bukowski – a man whose oblivion-to-cult-status story is so compelling, websites are now devoted to him all over the planet. Can you imagine any establishment-propped poet laureate achieving such ubiquitous cult status? Walt Whitman – who balanced giving birth to American bohemia with weaving a body of work which makes him a University syllabus staple to this day - is rightly described as “a proto-hippie and sensualist who celebrated the dignity of work, a gay man who wrote lyrically of the male body” by literary scholar Joel Dinerstein in his excellent 2014 tome American Cool: a description that becomes all the more surprising when one considers that Whitman’s most famous work, Leaves of Grass, was published in 1855. Robert Burns had 12 children by four women, is Bob Dylan’s greatest influence and had more nicknames than the average rapper ("Rabbie Burns", "The Ploughman Poet", "The Bard of Ayrshire").

And what of the coolest set of all – the romantic poets? Like the coke-addled rock stars of much more recent times, Lord Byron inspired fashionable young blades on British university campuses to emulate his look, cropping their hair and wearing it powderless and waxless and sporting open necked shirts and silk lounging garments. By 21 he was riddled with gonorrhoea and syphilis following affairs with actresses, society women and a few young men. His opiate use rivalled that of Lemmy, Ozzy or Keith, and he once tried to get a tame bear enrolled as a fellow student at Cambridge. Byron eventually died in Greece, having joined insurgents in their war of independence against the Ottoman Empire. “Cool” barely tickles the surface.

So what went wrong? Why are the words “I’m a poet” now about as much of an aphrodisiac as “I expose myself in playgrounds”? Sadly, at some point between the 1960s counterculture explosion and the present day, the penning of verse lost all of its hip factor, and recent movements like New Formalism – which promotes a return to metrical and rhymed verse – have done nothing to inject it back. Of course, the whole rap movement has piqued youthful interest in well-constructed verse: but the consumption of stanzas, printed in ink on paper – for pleasure? Zip.

"Phonaesthetics, metre and dense symbolism evoke the square root of nothing in the iPhone generation."Part of the problem is that verse, these days, is unchartered literary territory to the masses. Whereas a play resembles a film – a narrative unravels via an enactment of scenes by performers – and prose bears some resemblance to the coherent sentences and ideas structured by the grown-ups around them, phonaesthetics, metre and dense symbolism evoke the square root of nothing in the iPhone generation, and their demands for instant gratification are uncompromising. And so, they fkg h8 it. Meanwhile, people born in the early-90s are now old enough to enter the teaching profession - hence a recent Ofsted report in the UK finding that poetry is the worst taught of all literary forms, with many teachers lacking confidence even understanding it, let alone teaching it. With an entire generation’s exposure to poetry now generally limited to reading Kipling’s “If” on the back of a friend’s parents’ toilet door, it’s surely time to hike poets back up to their traditional position in the upper tiers of cool. This is a special breed of human who has been incarcerated the world over, thrown into Soviet gulags, for answering the call of their muse (or conversely, as in the case of Ancient Greek choral lyric poet Alcman, released from slavery for their talent). The poet, as a species, has suffered enough for his art, without suffering the ignominy of redundancy and irrelevance. Sadly, the only way I can see it happening is by forcing the young drips appearing on America/Britain’s Got X-Factor Idol, or whatever it’s called, to sing the words of Ode On A Grecian Urn to the tune of Taylor Swift’s latest bubble-gum ditty. And I can’t see Simon Cowell approving.