Soft Wear: Steven Hitchcock

As our month exploring travel and speed draws to a close, The Rake proposes an alternative source for lightweight, travel-friendly tailoring, namely the leading proponent of modern British drape, Steven Hitchcock.

It’s a rare thing in menswear to discover clothing that brings with it a palpable sense of nostalgia and tradition, and yet which also feels particularly current. One might think me mad for comparing the generous lines and gently flowing silhouettes of the finest drape suits to the undulating curves of the statues in the Piazza della Signoria, or the golden locks flowing effortlessly over the shoulders of a Botticelli, but there is unquestionably something effortless about the drape cut. A school of tailoring originating at the turn of the twentieth century, characterised by softness and fullness of shape (as pioneered by London-based Dutch tailor Frederick Scholte) and its literal ‘drapey’ quality, English drape at its best harks back to a former era of glamour, prestige and discreet tastefulness.

I’m pleased to report moreover, that these values continue to form the cornerstone of the drape-school of British tailoring today, at the forefront of which is one particular denizen of soft suiting, Steven Hitchcock. A stalwart of British tailoring, Steven spent years plying his trade under his father, John Hitchcock, former Head Cutter and near-mythical figurehead for Anderson & Sheppard. Indeed, it was his father that introduced him to the art form in the first place – and the drape cut. Even so, despite school holidays spent in Savile Row workrooms, Steven didn’t set out to a be a tailor, “I always liked working with my hands” he quips, “so I started a course in mechanics, but my granddad said ‘why don’t you go and work for your dad for a week?’ I did one day, and saw Elton John pull up and go into Richard James next door and then Dario from Huntsman nearly got run over by Robbie Williams in his Rolls Royce.” Evidently such bizarre events were intriguing to the young Steven: “I just thought ‘this is alright, this’ – living in Enfield you don’t really see much, but if you come round to Savile Row and Piccadilly with all the lights and everything – I just thought it was really interesting.” From there, it was apprentice coatmaking, “my father said the best thing to do was to learn coats” and thence on through nine years of cutting and tailoring at Anderson & Sheppard.

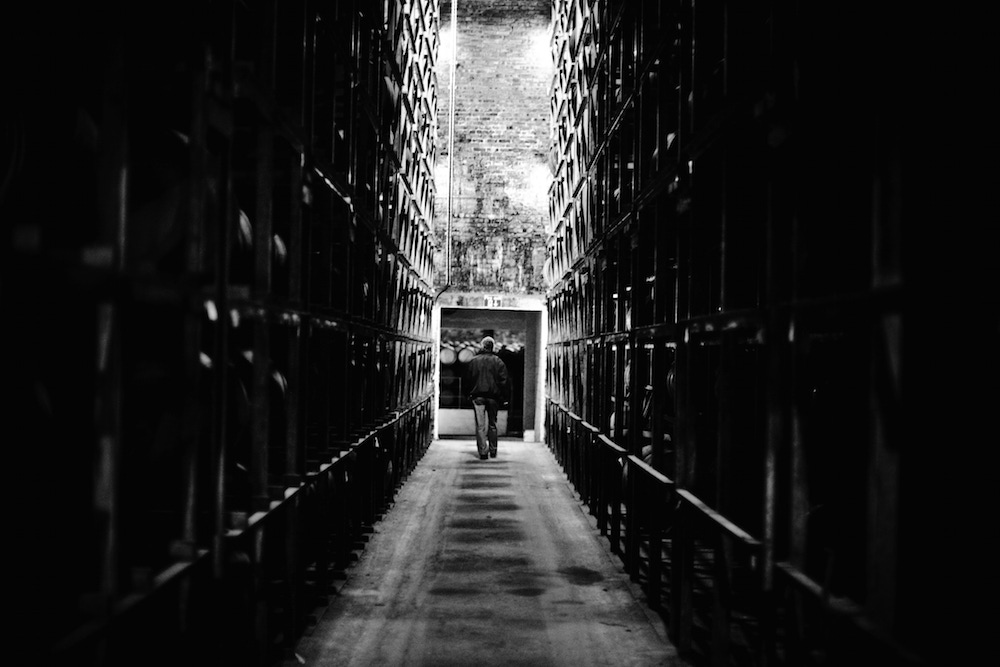

Steven made the momentous decision to leave Anderson & Sheppard in 1999 and never looked back, occupying a number of different premises on Savile Row before settling in the renowned ‘tailors den’ on St George St, sharing the shop with Denman & Goddard. What’s more, having his name over the door has always allowed him to (as he puts it) keep control of his work. “I’m seeing every job through myself. I make three suits a week completely by hand, with a small team. I’m just trying to make the best suits I can with my name on them”, he explains. What he really means, is that as a small independent tailor, he doesn’t send work out to other workshops – all the work is done under his eye, ensuring consistency of make and quality.

What’s more, when Steven set up on his own, he decided to use his independence as an opportunity to take what he’d seen and learned on the Row, and to elevate the traditional British drape cut. Taking the fullness of a conventional drape coat and an almost radical lightness of canvassing, he works more shape into the coat through the waist and front than has otherwise been achieved. “Traditionally, a drape-cut suit uses two fish-cuts in the front of the coat, which adds a minimal amount of shape. I put a belly cut in, a pocket and a side-body that creates shape. I’m still cutting a drape coat with a soft round shoulder, but there’s more shape running through the waist". As you’d expect, Steven’s shoulder padding is also minimal (no pre-fabricated pads are used) and are designed to feel soft and form fitting on the body. For his canvasses he uses only a single layer of the best Silesia, which keeps his chests feeling light and natural “it’s expensive, but well worth it” he notes, padded with “long, loose” stitches. “Coatmakers that haven’t worked with me before laugh when I ask for these stitches”, he says, “but I ask for them because they keep the chest soft but give it springiness and a hint of three dimensionality.”

Also crucial to Steven’s cut is the interplay between collar, back-neck and armhole. The armhole is particularly high, skimming one’s armpit as it were (not something that one might expect of a drape suit) and the suit’s collar and back-neck are both cut as close to the body as can be – ensuring that the distance between arm and neck is as small as possible. This keeps the coat firmly anchored on the neck for maximum manoeuvrability – one can’t help but get the impression that you could swing along a set of monkey bars in a coat with such a tight collar. Fred Astaire used to dance in drape coats and tails cut like this on the silver screen, specifically because he could jig about in the confidence that his collar would stay put with no danger of it standing off the neck.

"You can roll it up, get off a plane and it behaves beautifully."In short, Steven’s work represents a deceptively simple and elegant concept, but is composed with a technically demanding cut, designed to achieve an effortlessly clean, smooth aesthetic. Moreover, because lightness and comfort are so important to soft tailoring, Steven’s work travels effortlessly. It makes sense then that more and more of his customers have been coming to him for clothes to travel in: “A lot of clients are after travel clothes and that’s why we sell high-twist worsteds and fresco. You can roll it up, get off the plane and it behaves beautifully. We’ve made a lot of blazers from it this year for customers who want something slightly more casual, and something that travels easily. “We’ve also been making more sports coats – you can always wear a jacket even when a suit is too much – they’re ideal for clients that want to look elegant when they go out somewhere, or when they’re on the move.” In a world that is moving ever more quickly then, the deeply traditional aesthetic of drape suiting takes on an entirely new relevance, and that’s key to what Steven offers. As Steven says, “it makes you look like you – it doesn’t make you stand up straight like a soldier. That’s the danger with a military tailor, all the shoulder pads are exactly the same and everyone walks out looking the same. Soft tailoring is very individualistic, it’s very elegant and it relies on a more natural use of shape.” Naturally Steven is biased, but there’s no doubt that he has a point - the lack of firm padding in his clothes does lend itself to an easy-wearing aesthetic. It is no great secret that the lightweight, unstructured approach mastered by so many significant Italian tailors is a seminal go-to style for the frequent traveller and rightly so. Nevertheless, Hitchcock’s work demonstrates that this need not be the only way; the travelling rake in search of a truly elegant look, which nonetheless offers mobility, comfort and breathability, could do a lot worse than pay a visit to No. 11 St George Street this season.