A Top Hat Investment

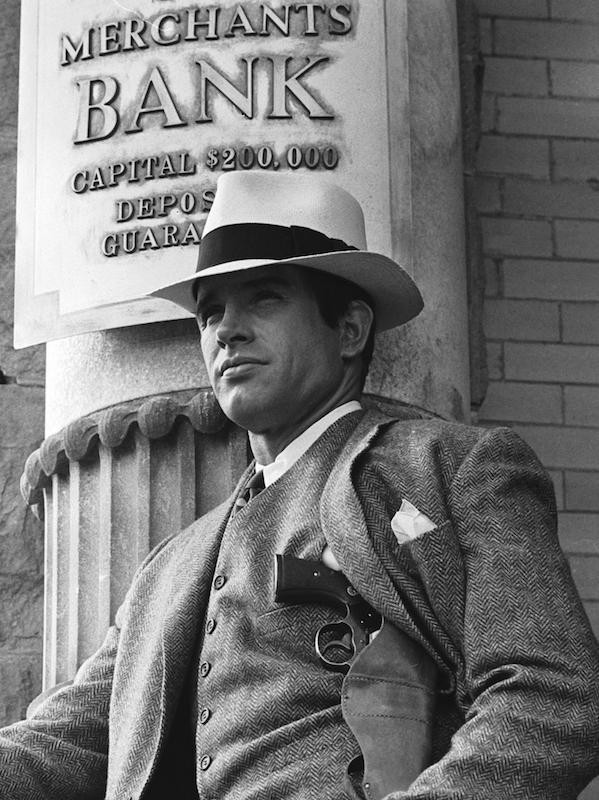

Purchase a straw hat for four or five figures? Assuredly, sir. Here’s why a finely crafted Panama is worth every penny of its price.

The trilby hat gets its name from the theatrical adaptation of the 1894 novel of that name by George Du Maurier — a stingy-brimmed lid was worn in the London stage production of the play, leading to ‘trilbies’ enjoying a surge in popularity. Another iconic piece of headwear also took its moniker from a play, Fédora, written by French author Victorien Sardou in 1882, which starred Sarah Bernhardt as a hat-fancying Russian royal. The Panama hat, meanwhile, takes its appellation not from a play, but a place — though rather confusingly, not its place of manufacture.

Produced in Ecuador, the best of them turned out in the province of Manabí, Panama hats bound for export in the 19th century were first transported to the Isthmus of Panama (the narrow South American landmass separating the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea, now bissected by the Panama Canal) before being laden on ships sailing to the United States, Asia and Europe. From the early 1800s onward, these fine plaited straw hats, woven from the leaves of the toquilla palm, began to be referred to by the name of their port of origin.

The highest quality, and most expensive, Panama hats are made in the Manabí town of Montecristi, which lends its name to the ‘superfinos’ that are the apotheosis of the Panama hatmakers’ art. These are made by the following process, unchanged for centuries:

1. The hatmaker hikes into the mountains and harvests carefully selected fronds of toquilla palms (known as ‘coggolos’, almost 50 are needed to make one hat), later removing the soft strips (‘tallos’) at their centre.

2. He boils and then gently drip-dries these spaghetti-like strips.

3. Smoking the tallos with sulphur bleaches the pale green vegetal matter off-white.

4. Cutting the fine, supple straw to the desired length, the weaver begins his laborious process, beginning with the crown of the hat (‘plantilla’) and meticulously working outwards and downwards, shaping the crown over a wooden form, then weaving outwards again for the brim.

5. Its edges left rough with about five inches of loose straw fringe around the brim’s rim, the hat is passed from the weaver to the ‘rematadora’, who loosely back-weaves the fringe to keep the hat from unravelling.

6. A craftsperson called the ‘azocadora’ then painstakingly, gradually pulls the weave tighter, working their way around the hat’s brim up to five times.

7. The ‘cortador’ cuts much of the excess fringe straw from the hat’s brim, saving the pieces to be used for seamless colour-matched repairs of the hat, should they ever be required.

8. The hat is then thoroughly washed with soap and water, line-dried, and again undergoes sulphur smoke bleaching.

9. A muscular gentleman known as an an ‘apaleador’ takes a hefty hardwood mallet and beats the hat — not too hard, nor too gently — against a stone to soften it, applying sulphur that will help give the hat its distinctive colour.

10. The cortador removes the remaining fringe from the brim and any other random straw, and finally, the ‘planchador’ irons wrinkles from the hat, pulling any stretch from it to permanently fix its size.

Though that all may sound deceptively straightforward, the process detailed in the steps above can take many months — and still, only results in an unblocked, unshaped hat: a veritable diamond in the rough. Today, there are only a handful of millinery maestros in existence (including America’s renowned Brent Black, and the artisans of storied British hatters Lock & Co, whose wares are purveyed here) possessing the savoir-faire required to do justice to these works of art, shaping them into one of the iconic Panama forms, such as the jaunty Havana, shady Plantation, classic Fedora, or rollable, centre-creased Optimo.

The time and craftsmanship involved understandably results in better Panamas fetching fairly hefty prices, anywhere between $400 for a very good example up to $25,000 for the most exquisite work. (Though Black says he’d part with the finest Panama he’s ever laid hands on, one that took its maker more than five months to produce, for no less than a hundred grand.) Of course, a half-decent, authentic Ecuadorian Panama can be had quite cheaply. But its weave will likely be disconcertingly uneven. Its colour a bit too white, indicating peroxide (rather than traditional sulphur) bleaching. It will probably have been hastily shaped and coated in a synthetic stiffening goop, instead of being lovingly hand-blocked over the course of a couple of days. Its sizing might be a stock-standard small, medium or large, not the minute increments that will guarantee a perfect fit for your one-of-a-kind cranium. None of that sounds terribly rakish, does it? All very off-the-shelf, industrial and distasteful.

We can’t imagine legendary Panama wearers such as Ernest Hemingway, Prince Charles, Sean Connery, Tom Wolfe, Peter O’Toole, or Teddy Roosevelt settling for anything less than the fully handmade real deal. Neither should you. Invest in a proper Panama, and enjoy the satisfaction of guarding dashingly against the sun’s damaging rays, while helping ensure the sun doesn’t set on this remarkable artisanal endeavour.