Crowning Glory

Originally featured in Issue 2 of The Rake, Wei Koh expertly examines how Steve McQueen’s magnificent wardrobe stole the show in classic 1968 heist film, The Thomas Crown Affair.

There’s a reason many of the smartest names in men’s elegance regard The Thomas Crown Affair, the 1968 film starring Steve McQueen, as one of the most influential moments in men’s style. To this day, the film remains one of the most empowering intersections between masculinity and sartorial expression ever captured by the camera’s lens.

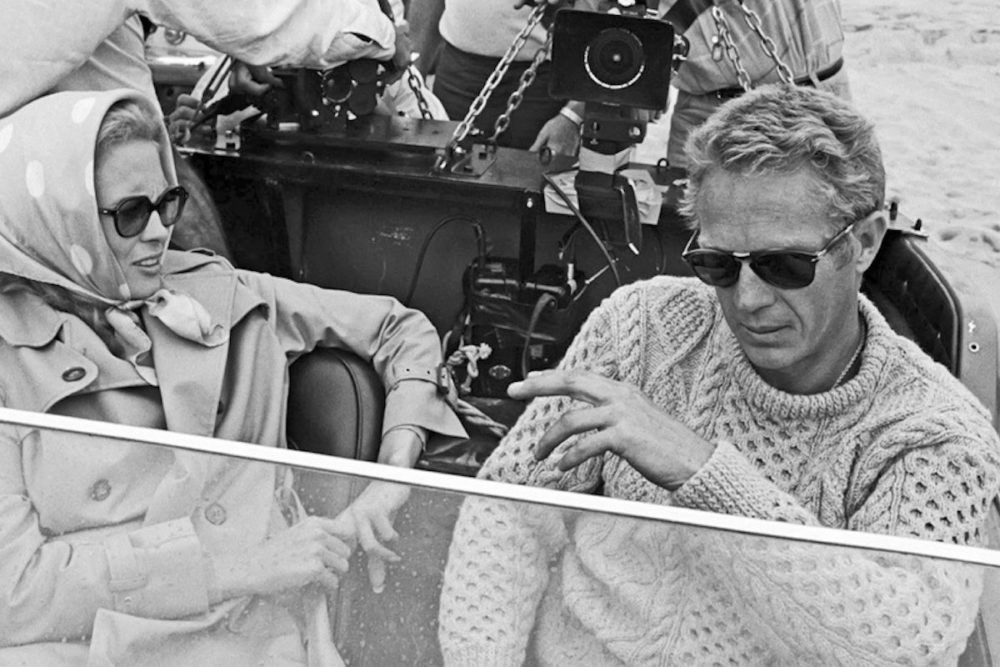

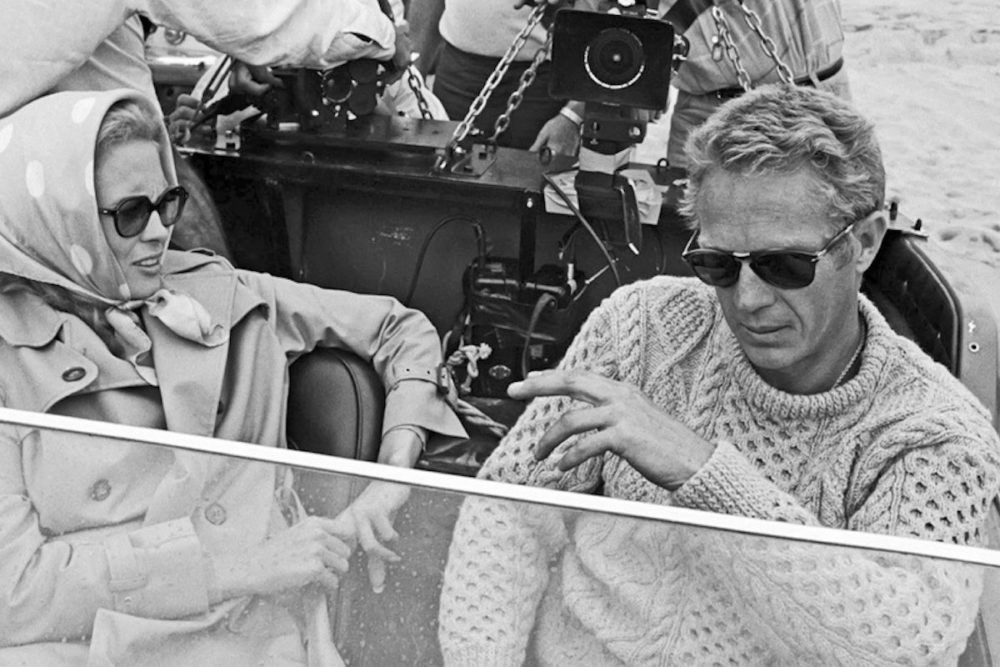

Created during an era when American cinema was focused on gritty social realism, it was perhaps understandable for reviewers to dismiss a movie like The Thomas Crown Affair — replete with Faye Dunaway’s 31 costume changes, Ferrari GT 250s, Rolls-Royces and, in particular, Steve McQueen’s British-tailored splendour — as mindless eye-candy.

Admittedly, the narrative foundation of the film is not the strongest. Its central character is a new-world Boston brahmin — the 36-year-old, divorced, polo-playing arbitrage specialist and self-made millionaire, Thomas Crown. Because his life is so coloured with ennui, he’s compelled to get his adrenaline double-tap by masterminding a daring daylight bank robbery using unwitting henchmen who don’t know his true identity. Enter Faye Dunaway, who plays a cagey insurance investigator — the cat to his mouse, engaging Crown in a duel of wits, emotion, and stylistic one-upmanship.

Agreed, the characters are underdeveloped and the plot is without true genius. As one reviewer put it, “If style could be purchased,” director Norman Jewison “has turned out a glimmering, empty film reminiscent of an haute couture model: stunning on the surface, concave and undernourished beneath.”

However, this comment entirely misses the point of The Thomas Crown Affair which, as a pure exercise in style, is as significant to cinema as Kazimir Malevich’s experiments in total non-objectivity are to art — which is to say, instrumental. Style is expressed in everything from the languid cool score, to the split-screen technique of the credits and bank robbery (a first unveiled at the World’s Fair of 1964 and used only once before in commercial film, by John Frankenheimer in McQueen’s Le Mans). The message is clear from the multiple images flashing in the opening credits: What’s more beautiful than one image of a perfectly tailored Steve McQueen? Well, multiple images of him as the bank-robbing Savile Row-suited Narcissus!

“There is none higher. It is the most stylish movie ever created,” says Mark Powell, the British sartorial impresario who invented the gangster-chic tailoring seen in the cult film, Gangster Number 1. Says James Sherwood, author of definitive Savile Row tome The London Cut, “It reconnects us with the passion we derived from military dress or court uniforms. It reminds us that in the centuries before, it was always the man, and not the woman, that was the style star.”

A joyous celebration of male sartorial self-expressionism, the movie resonated with a broad audience because of McQueen’s unique union of virility and elegance. There is nothing fey or foppish about ‘Tommy’ Crown. He is every bit an Alpha male clad in bespoke armour. McQueen had to overcome a great deal of studio scepticism on whether (given his rugged persona, both on- and off-screen) he could pull off the portrayal of a dashing, urbane tycoon. Yet, in much the same way that wardrobe transformed former bricklayer Sean Connery into a convincing gentleman spy, exquisite suits empowered McQueen to confound typecasting. Here, the clothes definitely made the man.

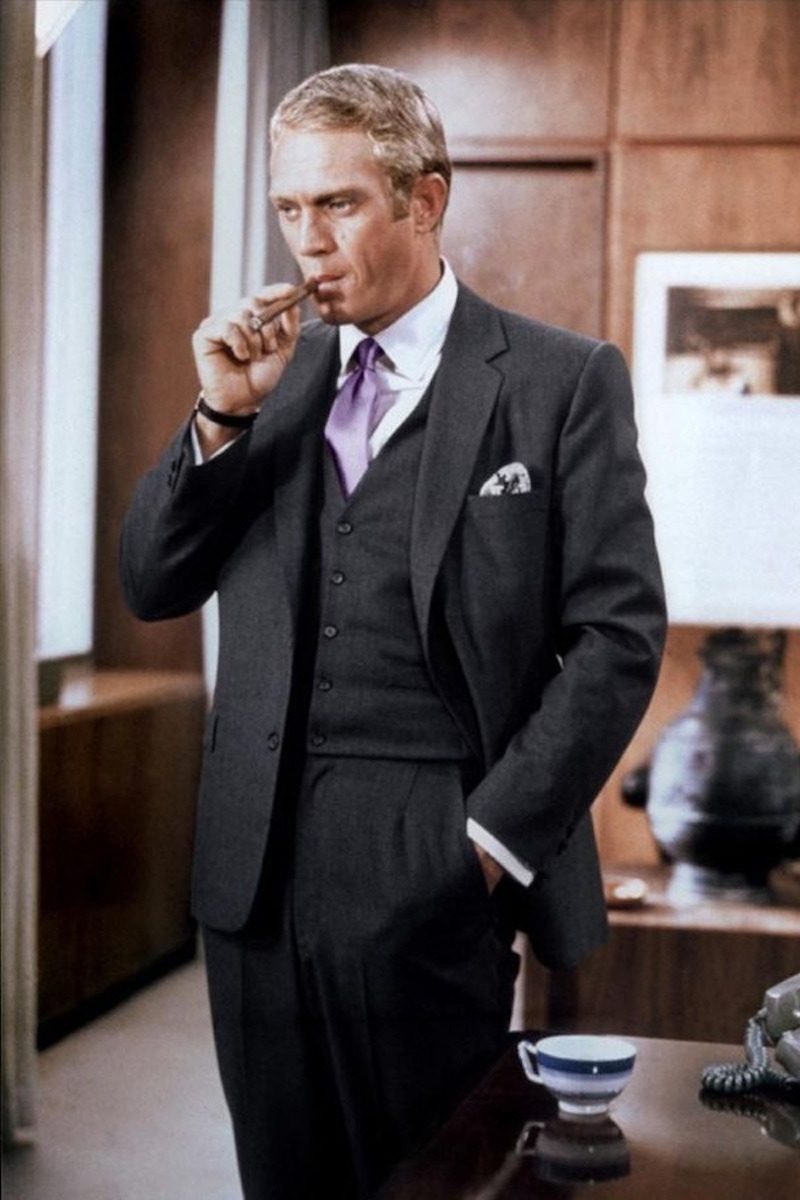

Every detail of his dress in the film is executed with perfect sartorial precision. There is never a misstep, though certain colour combinations (such as the outfit he wore to seduce Dunaway’s character: a soft-pink striped shirt, mauve necktie and silver black pocket square combined with a grey three-piece suit) certainly flirt with hyperbole.

It was British tailoring legend Doug Hayward, who also created Michael Caine’s suits in The Italian Job, that was tasked with outfitting McQueen in an array of attire to dazzle the senses. While there is a belief that McQueen’s suits follow the lean silhouette popular in men’s tailoring of the era, our examination of the film proves this inaccurate. Indeed, the suits created by Hayward are quite the opposite. They are perfectly representative of classic British tailoring, and as such would be completely relevant and stylistically correct today.

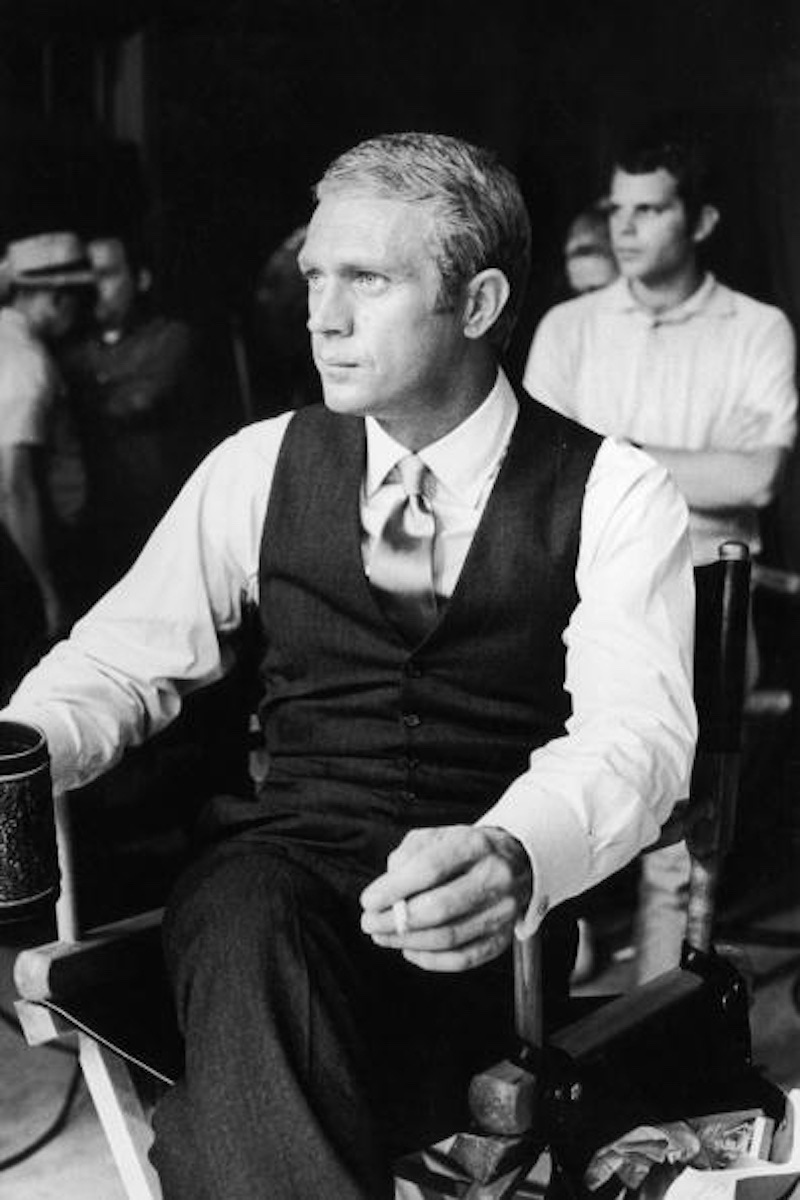

They are all three-piece suits that create an air of brash formality in sharp contrast to the rapidly devolving late-’60s world around McQueen. The shoulders are well structured and feature light roping to create a powerful, almost predatorial stance. Slightly slimmer lapels serve to build the expanse of chest. The coats are two-button with well-suppressed waists to create a more Atlas-like silhouette. They feature bespoke hallmarks such as large sleeveheads and slightly more voluminous backs to aid mobility. There are even some downright cheeky details like the single-button, fishtail-sleeve cuffs on several suits, including the legendary grey Prince of Wales suit in the opening scene.

The waistcoats in the movie are generally without lapels and are straight-cut at the hem with a slightly higher line to give greater length to McQueen’s legs. The waistcoats are all buttoned at the last button, which is correct for a straight-cut hem. Though McQueen’s plain-front, high-waisted trousers are relatively full, they end in narrower hems to marry with his slim British benchmade shoes.

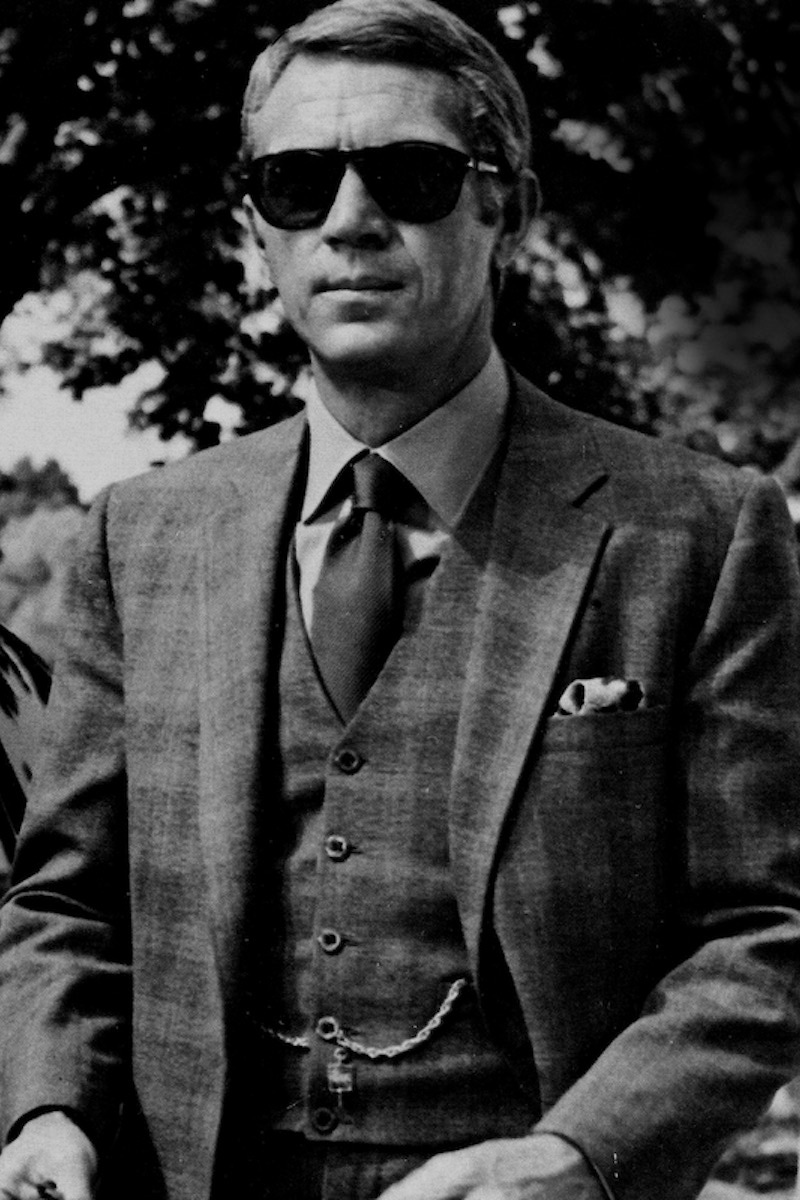

Masculine elegance has never found a more pure expression than in the film’s first scene. Here, Crown checks his gold Patek Philippe pocket watch, which is hung double-Albert style with a fob drop. He is resplendent in a glen plaid three-piece in contrasting shades of grey. The details of his suit are extreme, from the super-high side vents to his roped shoulders to his single-button cuffs. His light blue shirt with large mother-of-pearl cufflinks is counterpointed by a royal blue silk tie knotted with a dimpled half Windsor. The lenses of his Persol shades match the shocking blue lining of his suit. A dove-grey pocket square, staged ‘Astaire Puff-style’ fills his breast pocket. Full of devil-may-care cool, it’s a crazy ensemble, an almost totally over-the-top piece of sartorial bravado… but it works. Says tailor and cinematic costumier Timothy Everest, “It’s this outfit that made me want to become a tailor.” McQueen’s clothes continue to shape-shift in each scene, from the charcoal-grey three-piece in the Swiss airport, to the oddly centre-vented blue/grey pinstripe three-piece in his banker’s office, to what is perhaps the most stylish of the suits in the film: a midnight-blue outfit with a gorgeous double-breasted waistcoat worn with a subtly striped shirt with a collar pin and a four-in-hand-knotted, double-pleated tie. Faye Dunaway’s character is asked, “Do you find him handsome?” “Yes,” she gushes — and we can’t help but agree. Today, as men get reconnected with classic elegance, the film is more relevant than ever. Because encoded in its every frame is the message that it is your right to look magnificent. This article originally appeared in Issue 2 of The Rake.