Eric Giroud - the man with time on his hands

The Rake caught up with legendary watch designer Eric Giroud to dial into his creative process.

“The funny thing is,” says Eric Giroud, “I’m not that into watches. I remember receiving my first watch when I was about 13, probably a cheap one, but the watch itself wasn’t so important as what it signified - which was becoming a man. Before I took up watch design I didn’t wear really a watch at all. Oops. I do wear one sometimes now, but I don’t like to change my watch too often, as some men do.”

Giroud, as this little irony would have it, is one of the world’s leading watch designers, despite the fact that you’ve probably never heard of him. He’s the man behind pieces for the likes of Vacheron and Boucheron, Van Cleef & Arpels and Harry Winston, Romain Jerome, MB&F and Tissot, among some 60 brands - most of which he isn’t allowed to name, but most of which you probably can. He’s won at the Geneva Watchmaking Grand Prix - the Oscars of watchmaking. He is, some say, the spiritual heir to Gerald Genta.

Yet Giroud came to watch design something by accident. Trained and working as an architect - “I wasn’t very good,” he concedes - it was only during his 30s, when his wife suggested they go skiing with her extended family, that life took a turn. “There was this very cool old guy there, who wanted to talk about watches and show me some books about watches,” laughs Giroud. The man - Giroud’s wife’s uncle - was Jack Heuer, the watch industry legend behind Tag Heuer. It opened his mind to a new, rather quiet line of work.

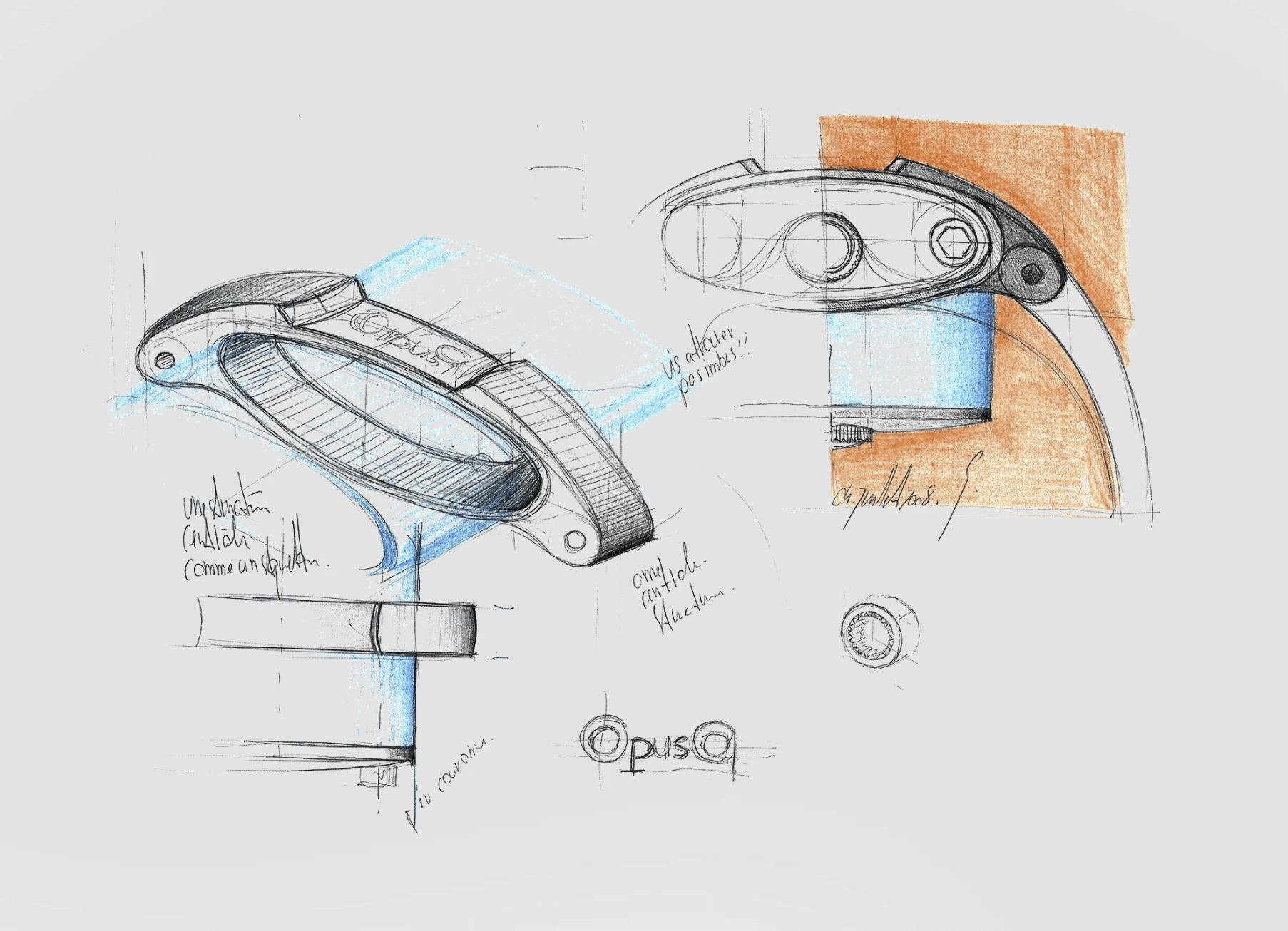

“I work in a monastery, in effect,” he says, of his isolated office, where he sits down at 5am, and sketches through to lunchtime, when he might print out a to-scale image of his latest design, cut it out and wrap it around his wrist to see how it feels about it. “That’s why I stop properly for lunch and go out. I need to spend time around some other people. It’s good for ideas too. And the ideas can come from anywhere. I was struggling with one project the other day and then I saw these amazing cookies, and that was enough to get me thinking afresh about the dial.”

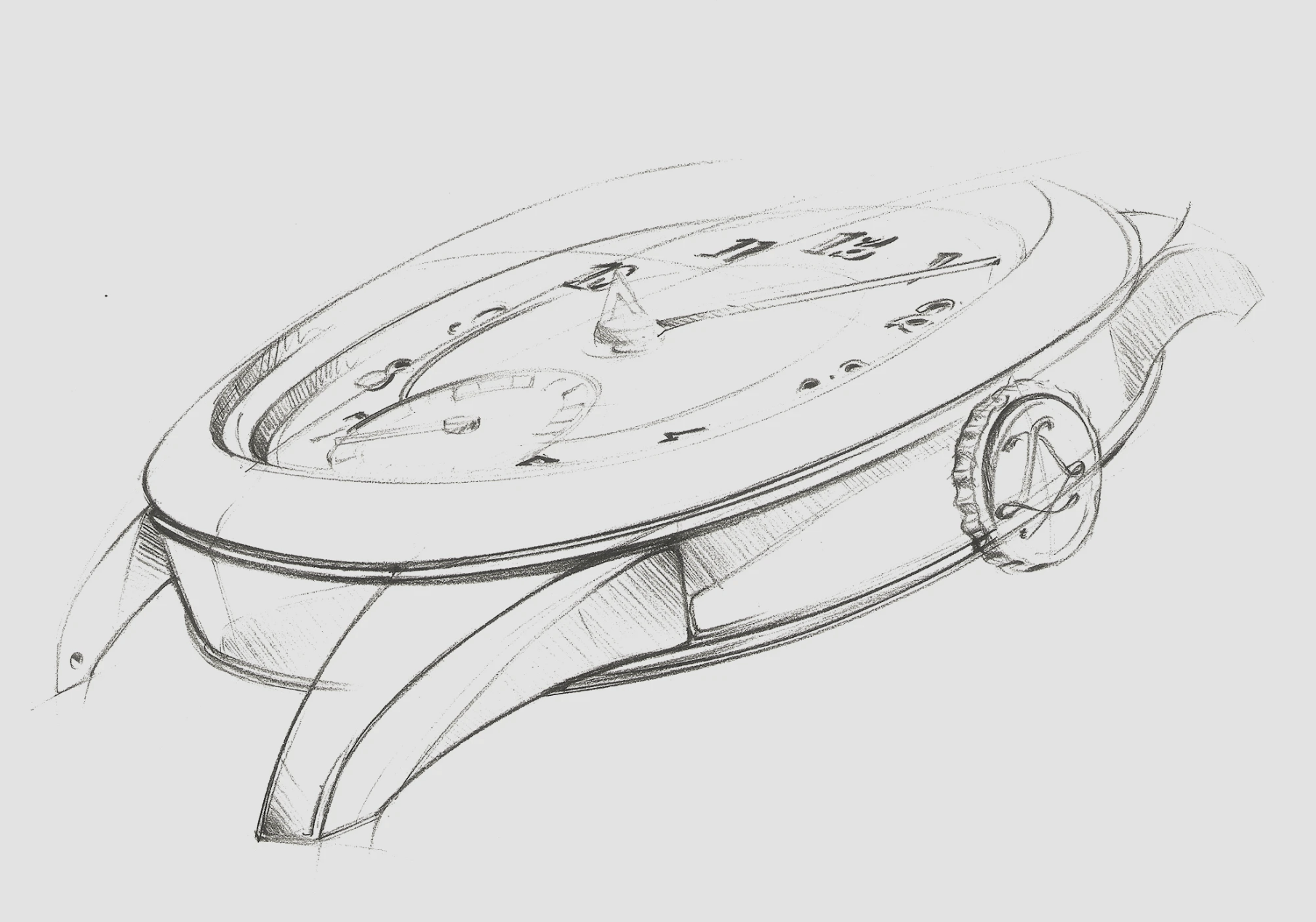

The Eric Giroud-designed MB&F HM8

The Eric Giroud-designed MB&F HM8

Giroud’s success arguably comes precisely from the fact that he’s not obsessed with timepieces - he approaches designing one of them much as he would any other object, be that a perfume bottle or kitchen knife, objects that he’s also had commissions to design, along with lighting and mobile phones. It is, he contends, that so many watch designers come up through the watch industry that they tend to have such a narrow focus; it’s why there’s an endless run of what he calls “nice but boring” classic designs.

“But, as an independent designer, when you’re designing someone’s house, you have to remember it’s not your house,” he says. “You can’t impose your own vision of what a watch should look like on every design. You have to design what the client wants for their customer. Of course, at the end of the day all watch companies tell me they want the same thing - they want a watch that is ‘beautiful’. Well, OK. But sometimes a really great design is the product of luck. There’s a magic to the process.”

That’s why Giroud insists he has no design signature, though he does always seek to introduce what he calls “a certain tension” to every design: he cites an edition of Jaeger Le Coultre’s famed Reverso, one that came with a bold red dial. “That tension between this modern, atypical colour and what is an old-fashioned looking watch is what makes it interesting. Look at any iconic watch design and that tension is there.”

Indeed, what he’d really like to design is clothing - with the exception perhaps, of socks, which he almost never wears, and black, a dour shade he’s never liked, “and I say that as an architect,” he jokes. He says he envies the greater freedom fashion designers have - to explore combinations of shapes, colours and materials - even if his style is rather minimalistic and masculine, with the occasional giving vent to his love of Gallic stripes. “And, as someone who designs watches every day, which can feel like you’re doing the same thing all the time, you need to have your mind opened by looking at the way other design works,” he says. “I need to restart like a computer now and then. I need to go clothes shopping.”

“Really every product has its own design criteria,” Giroud explains, “and, of course, a watch is something you wear too, and that’s regardless of how crazy the look of the watch may be - it has to be something you can put on. It’s also very small. It’s a limited canvas to work on. And it usually has to be waterproof, so there are technical limitations too. In fact it’s easy to design a watch that looks good on paper. But I know a design has to work in 3D - and that’s very different. It’s like seeing a shirt in a magazine and thinking ‘wow!’. And then you get it on and it’s ‘no, no, no!’.”

Is watch design getting better? Might we be tempted to step away from the watch world’s design icons in favour of something more progressive, more interesting, less historical? Giroud says there’s been a sea-change over the last decade, in large part because of a flurry of new, internet-enabled brands, “so it’s getting harder to stand out without good design,” he stresses.

“That said,” he adds, “when I go to present a design - when I’m looking for that light in their eyes, or not - often there’s still not that much said about it. All anyone really wants to talk about is the celebrity attached to the launch, or the movement. All that talk of tourbillons and complex mechanisms. I sit in the car after a meeting and think ‘what was that all about?’.”