George Best: Dribbling Genius Who Lost His Footing

Nothing can diminish the memories of George Best's peerless, often breathtaking quality of football and his dazzling presence off the field, despite being dogged by an array of highly publicised problems.

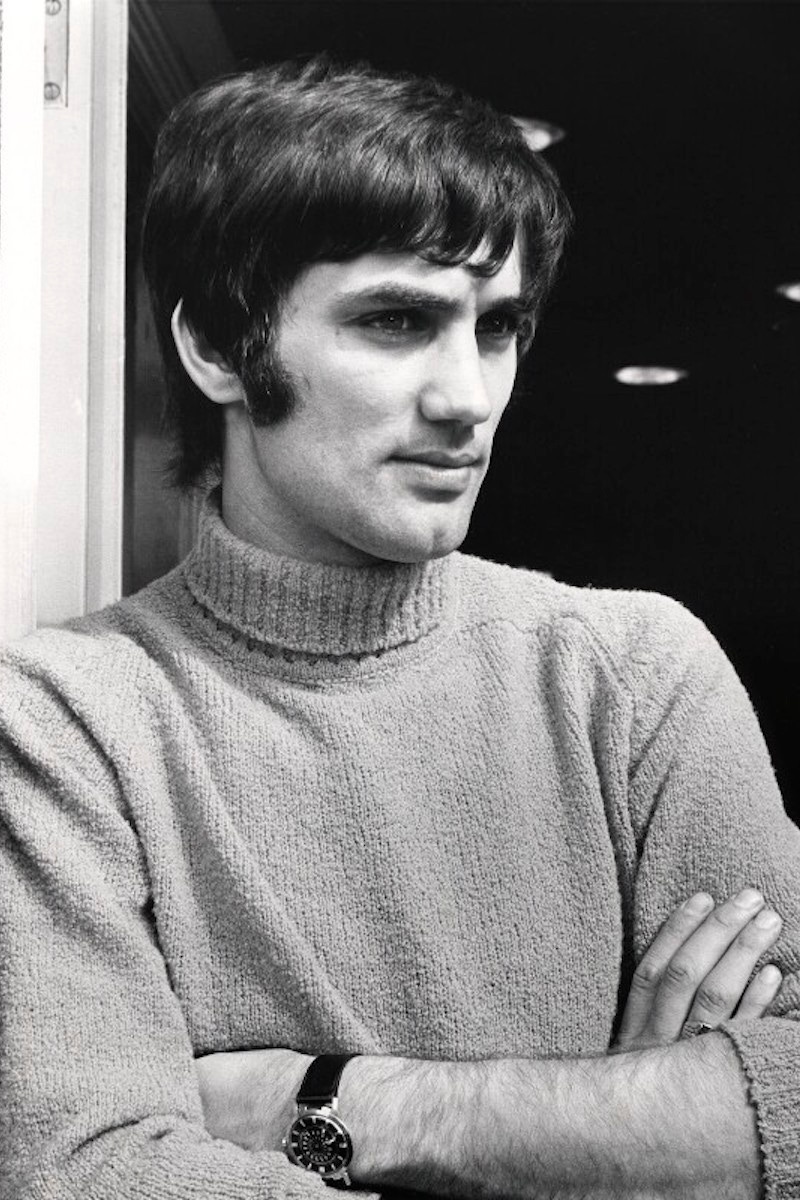

“Boss,” said talent scout Bob Bishop to Matt Busby in 1961, “I think I’ve found you a genius”. Bishop was not wrong. The 15-year-old Northern Irish lad he’d just seen play would go on to be called the greatest football player in the world - by Pele. Off the pitch he’d be referred to as ‘the fifth Beatle’, because he was, it seemed, just as big as the band. Indeed, Glentoran, his local club, had done an EMI, rejecting him as “too small and too light”. Manchester United wouldn’t make that mistake.

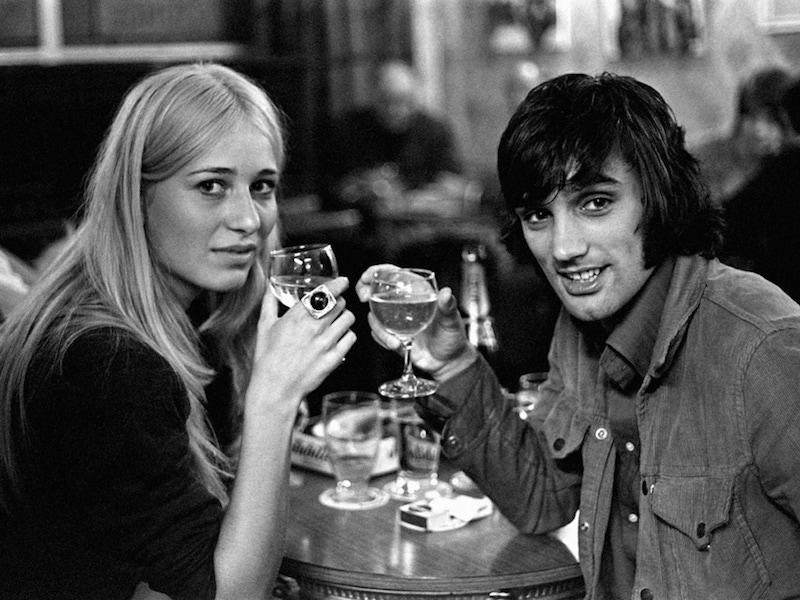

George Best was aptly named. His skills as a winger, dribbler of the ball and finisher were without parallel - next year marks the 50th anniversary of his legendary FA Cup record of six goals in a single match, which saw him invited to Downing Street to meet PM Harold Wilson, a man who’d written fan letters to the player. Best’s athletic talents, in fact, were trumped only by his reputation as a man about town, womaniser and - fatally - as a drinker. “If you’d have given me the choice of going out and beating four men and smashing a goal in from 30 yards against Liverpool or going to bed with Miss World, it would have been difficult choice,” he once noted. “Luckily, I had both.”

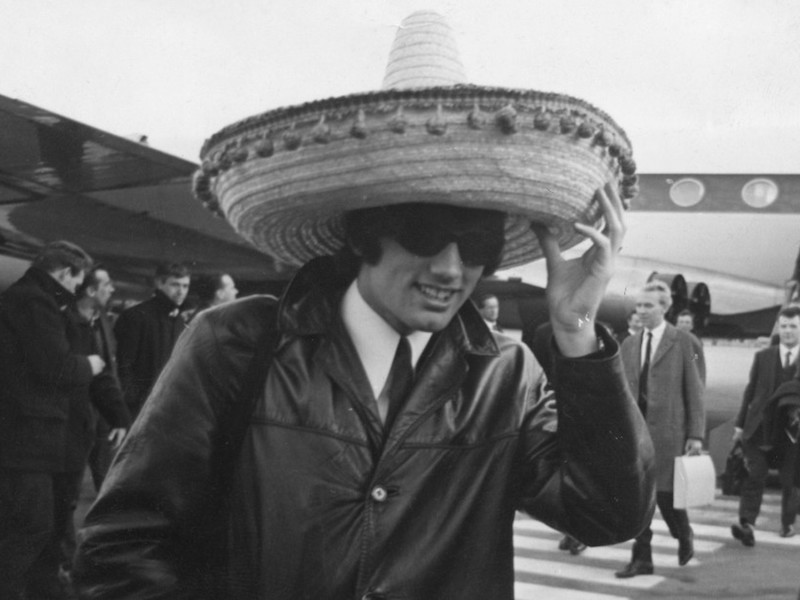

Indeed, Best set the bar for what was a new phenomenon: the celebrity player, one who re-purposed what had become a humdrum, grey, working-class sport for the era of swinging teens and pop culture, in Best’s case one who had to hire three full-time staffers to cope with the 10,000 letters he received every week. Best was also the first footballer to parlay his status and his looks - the allure of which he was all too aware - into other ventures.

It wasn’t just his unusually long hair - football was still a decidedly hetero world when he became a pro - that got Best football’s first fashion-led endorsement deal; though certainly his hair was much better than that captured by the widely-mocked life-sized bronze of the player, unveiled at Northern Ireland’s national football stadium Windsor Park earlier this year. It wasn’t his sideburns or even those celebrated blue eyes. It wasn’t just that he liked standing out - he was the first player to wear his football shirt not tucked into his shorts, a small but much-emulated act of defiance against the old guard.

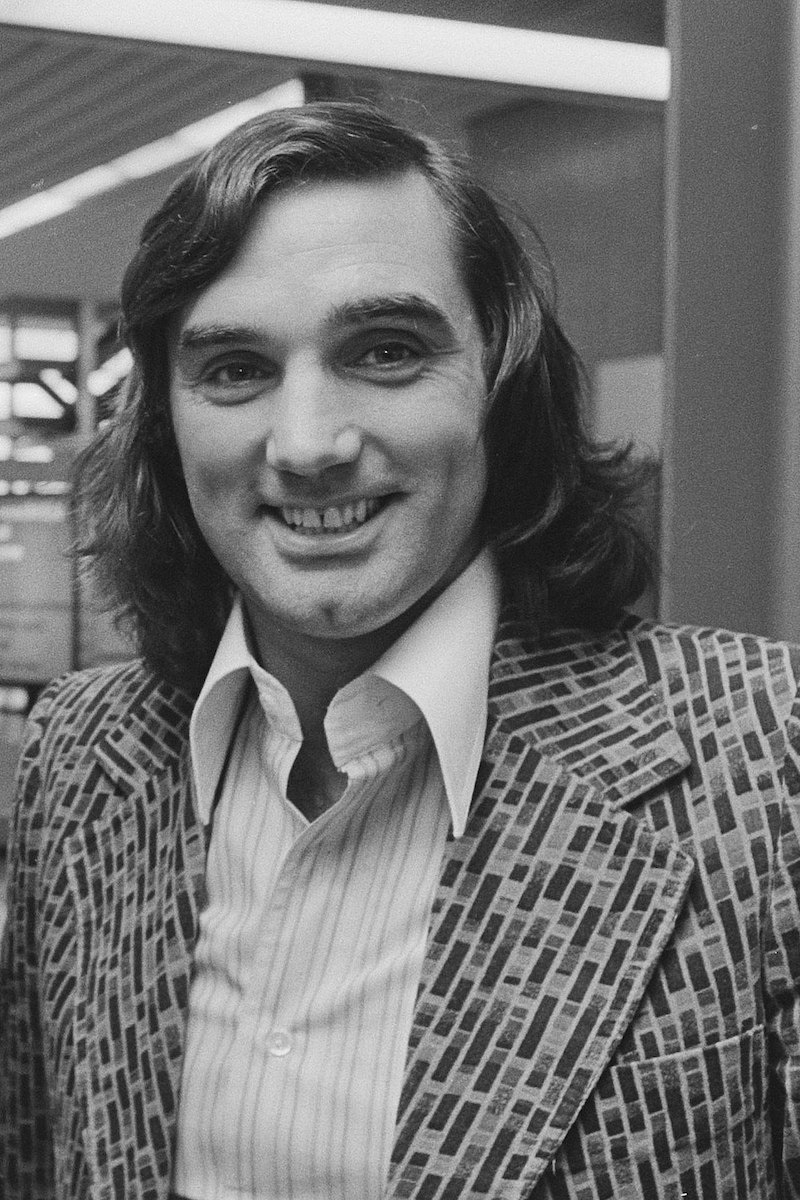

Rather, Best took his interest in fashion - and his eye for business - seriously, in 1967 going into partnership with fellow player Mike Summerbe to open his own chain of menswear shops, by turns called Edwardia, Rogue and the George Best Boutique. Then he opened hair salons and night clubs, the latter together with Malcolm Wager, his personal hairdresser, naturally. In times before celebrity was anything other than a US import, George Best pictured in a pink round-collared shirt and double-breasted velour jacket, leaving the grounds in his jet black E-type, was an image that defined British lives.

It was, of course, the excesses for which Best would be remembered, his talent for a one-liner defusing any envy, his undiminished talent as a player granting him a degree of free license. Such lines are so delicious, they’re hard to avoid repeating. But they define his life and times. “In 1969 I gave up women and alcohol,” he once noted. “It was the worst 20 minutes of my life”. “I spent a lot of money on booze, birds and fast cars. The rest I just squandered,” he once explained. Oscar Wilde, as far as we know, never played football. Best was outspoken too, about players he admired, but also those he thought were not up to much: “[David Beckham] cannot kick with his left foot, he cannot head a ball, he cannot tackle and he doesn’t score many goals. Apart from that he’s alright.”

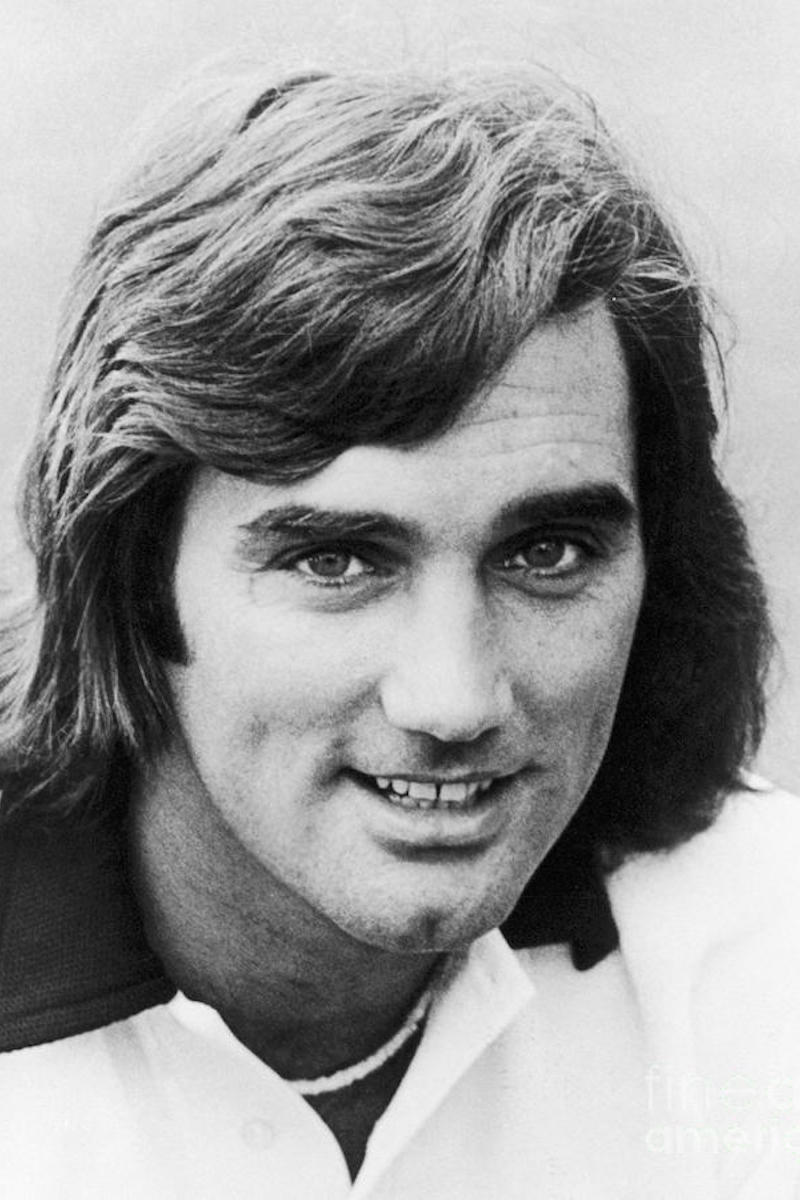

Those excesses, of course, are what did for him. The peak years of his playing career in Britain were all but over by the time he was just 27 - and that was five years after he’d won the league title, European Cup and European Player of the Year award. Famously, this flawed man was less the gentleman and struggled with the booze - he once took money from a woman’s handbag to pay for the next round, and he died, aged 59, following complications relating to the drugs he had to take after receiving a liver transplant (and, yes, he’d kept drinking afterwards).

But long before then he seemed torn between his immense skill and the lifestyle it afforded. He was regularly fined for misconduct. He was suspended by United after missing his train to match against Chelsea in favour of a weekend with Sinead Cusack. Later he’d fail to turn up for training for an entire week in order to spend the time with Miss Great Britain. He was finally put on the transfer list after going missing again - somewhere in London clubland. His priorities were some place other than on the pitch. That all came too easy.

Apologists have claimed that Best was simply frustrated with Manchester United’s failing performance - and on occasion Best said he felt that he was carrying the team. But old habits die hard: moving to South Africa to play for Jewish Guild, he’d miss further training sessions. He played more consistently in the United States through the 1970s but spent a lot of time at his new hangout, Bestie’s Beach Club, which he opened on Hermosa Beach.

At least it was sunnier than Manchester. But it seemed to many fans like an ignominious fading away for a man who, for sure, was a genius in sport and, perhaps, one in high living too. As the waiter put it in the the oft-told but no less apposite tale of delivering champagne to Best’s hotel room, only to find him in bed with Miss World and under a downpour of casino winnings, “Mr. Best, where did it all go wrong?”