How to harmonize separates

Disenchanted with wearing a suit every day, coordinating separates requires a certain dexterity to achieve the right balance and as Josh Sims examines there's many more fusions to envisage than people might think.

Tailoring is, no doubt, the apex of smart dressing for men. It’s hard to maintain any degree of formality to one’s attire without it. And yet the suit, specifically, while enjoyed for the craft, can leave one feeling a little corporate. It is, in part, why the idea of sprezzatura exists - the art of dressing with a certain considered nonchalance to affect individualism. But it’s also why a less well-known, equally Italian philosophy of men’s style also exists, that of spezzato.

That’s the splitting up of a suit in order to wear the jacket with the trousers of another suit (or vice versa). And while that might conjure outlandish images of a houndstooth worn with a bold check - risking that you look rather more like you’ve simply muddled your suits than rearranged them in some creative melange - this is not as crazy an idea as it might as first sound.

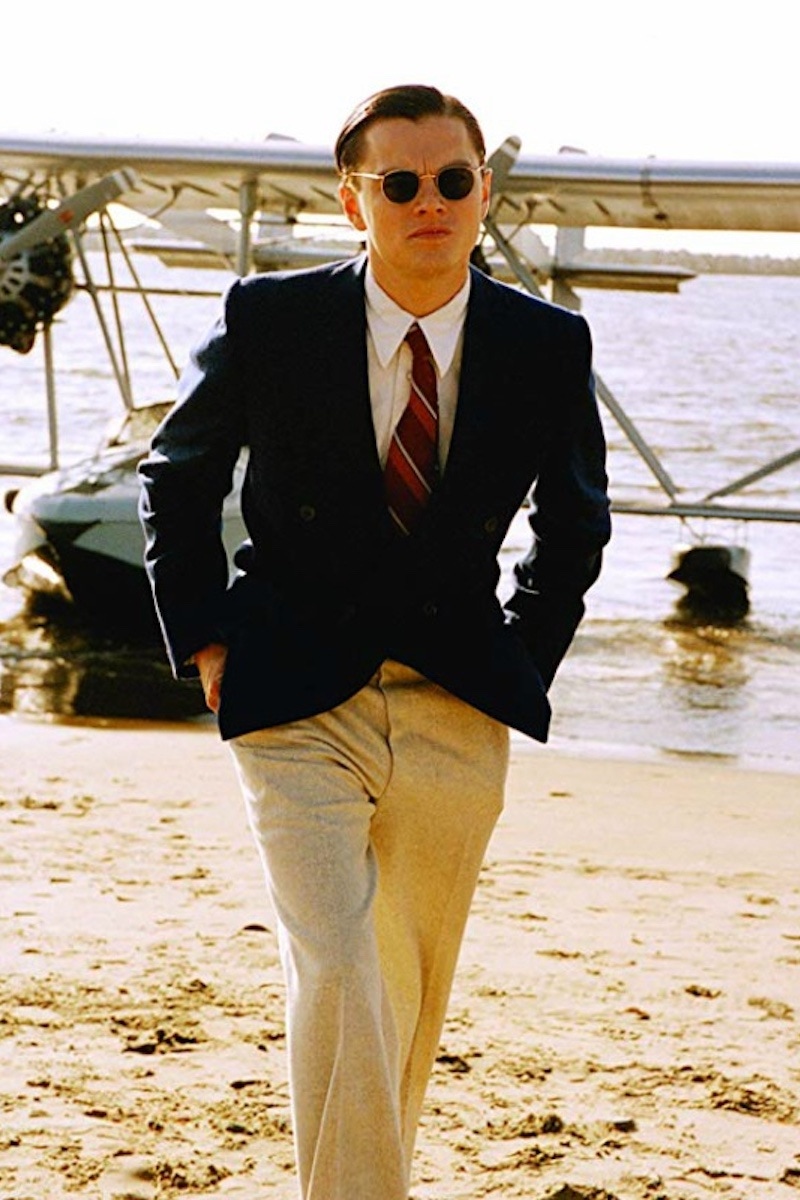

It works easiest with plains in complementary shades - a plain navy jacket worn with mid-grey or khaki trousers, for example - and likewise in complementary fabrics - lighter cottons with linens, wools with moleskins or other heavier weight cloths. Or when the pattern, or perhaps just the more textured cloth, is confined to the jacket. Indeed, that’s when your houndstooth or your bold-check might best come into play. Picture, for example, the jacket of a brown check suit from B Corner with the trousers from a charcoal grey suit from Cifonelli; or the jacket from Sciamat’s double-breasted suit in sand, worn with light grey trousers from a suit by Daks.

Certainly, while it pays to keep proportions in balance as well - a fitted jacket with more fitted trousers, a more relaxed cut with looser trousers, and so on - most important to spezzato is that there is some contrast between your upper and lower halves. A jacket and trousers that look as though they might belong to the same suit until closer inspection are not distinct enough to work.

But why go to the effort - and it is an effort - of trying to pair these two key components of more formal attire when there’s already something that was designed to do just that perfectly, commonly known as the suit? The problem is two-fold. For one, the suit, while highly practicable, can have less appealing connotations: conformity, for example; that cookie-cutter style in which self-expression would be somewhat contained were it not for a dashing way with accessories. Secondly, done well, it extends your wardrobe. Thirdly, there’s a case to make that, with work dress increasingly casual - softer, less structured - and yet often required to still have a degree of what recruitment types call ‘presentability’, spezzato is the way men’s dress is going.

Suggest the idea to a woman, of course, and she may well wonder quite what the big idea is. With the woman’s suit potentially even more loaded with unwelcome if complex associations - not least a supposed lack of femininity, which is why satirists often portrayed Margaret Thatcher in pinstripes - women have long worn what are called ‘separates’. It’s a term used since the early post-war years - and one that drives home precisely how such garments are worn too.

It was back in the early 1970s that US men’s clothing manufacturer Haggar first pushed the idea of men wearing tailored ‘separates’ too, rather than a suit - ever the pioneer, Haggar reputedly created the first pre-cuffed ready-to-wear trousers tin the 1940s and later introduced the first ‘wrinkle-free’ cotton trousers. The company saw its ground-breaking plan to sell jackets and trousers separately as having two advantages: it allowed those men who wanted to buy an off-the-hanger suit to get a better fit - and, by the way, Haggar also invented the trouser hanger that first allowed retailers not to display their trousers laid flat on tables; but it also allowed men to mix and match them too.

For all that the 1970s is typically derided for its men’s style - or supposed lack thereof - it all chimed with both a growing confidence in men dressing for self-expression, but also for comfort. Boomers didn’t want to dress like their dads. And their dads - if they were office-bound - wore suits.

Yet it’s also a term that has been largely absent when speaking of menswear for just as long. And that’s a shame: because a Camoshita United Arrows cobalt blue double-breasted jacket looks the bomb with, say, King & Tuckfield’s nutmeg brown trousers; much as does Magnus & Novus’ grey Donegal tweed jacket might with Edward Sexton’s Hollywood tapered trousers. Such jackets don’t have to be worn with just jeans or khakis. Such trousers don’t have to be worn with some nice knitwear.

Of course, the idea of wearing tailored clothing in a more casual manner was not a new one, even then: the combo of blazer and flannels was a classic look a century ago. Indeed, peruse menswear catalogues of the 1920s through to late 1930s especially - back when mail order was the way most men shopped - and well-drawn gents in separates were as commonplace as those in suits.

Following the rules laid down for the most formal of attire - black tie, but back when it was more typical to wear a white dinner jacket with black trousers - wearing, say, a plain Norfolk jacket in mint green with grey trousers, or a peak-lapeled double-breasted jacket in camel with trousers in ivory, would have been considered merely stylish. There’d even be a three-way use of un-matching separates: jacket, trousers and waistcoat. There was a sportiness to such dressing, naturally - hence ‘sports jacket’. But it was perfectly acceptable dress for all but the most formal of occasions.

So how did we become so dependent on the traditional suit, as far as our conception of smart dressing goes? One theory has it that the post-war labour excess - all those returning soldiers - demanded the suit’s more deliberate formality in order to get ahead. It was a ‘demob suit’, after all, that they were kitted out with for their return to civilian life. But then another has it that economic boom times - the 1950s for America, say, or the 1980s for the UK - saw the suit more as symbolic of getting ahead, so it was embraced even by those who weren’t.

But that was then. Menswear has undergone evolutionary leaps since then. Yes, the suit is still with us. But it’s time we rediscovered the joy of separates as well. Divide and conquer.