HYMNS OF THE REPUBLIC

His classic songs might try to gauge the ‘distance between American reality and the American Dream’, but Bruce Springsteen’s belief in the U.S., and his attraction to its totemic power, has been the consuming force of his life.

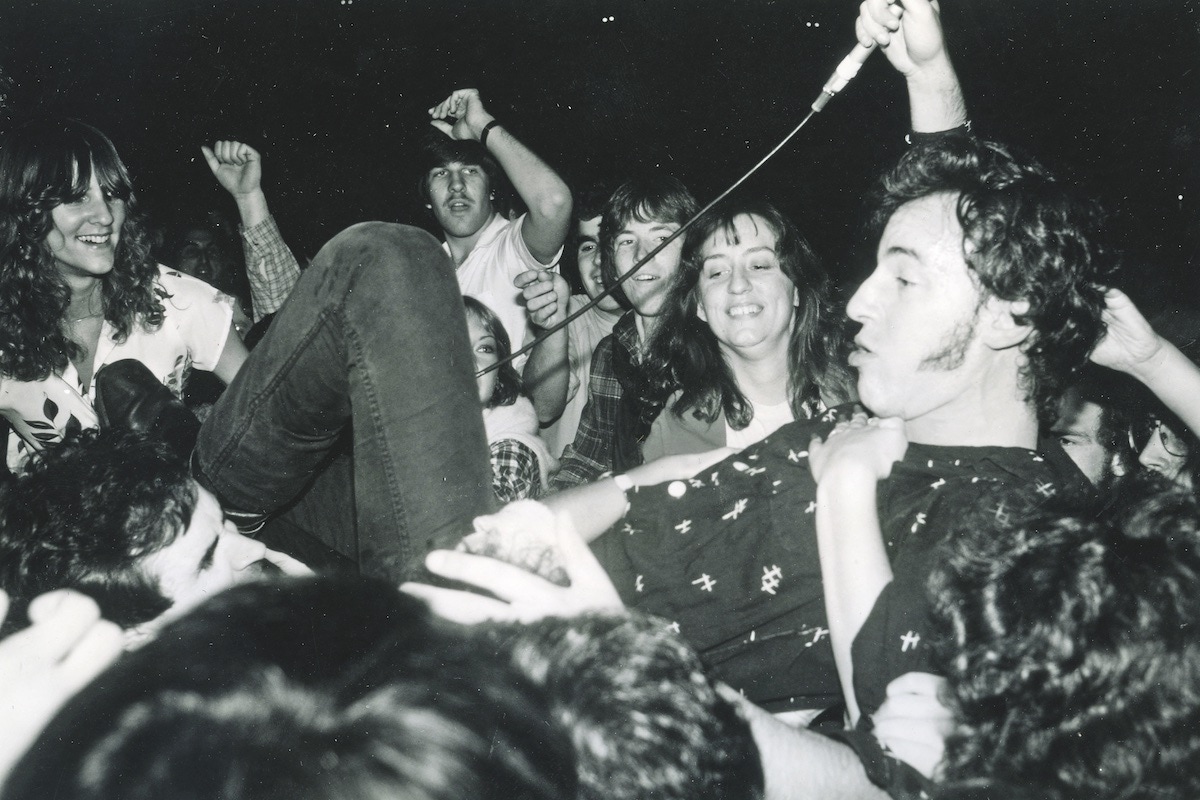

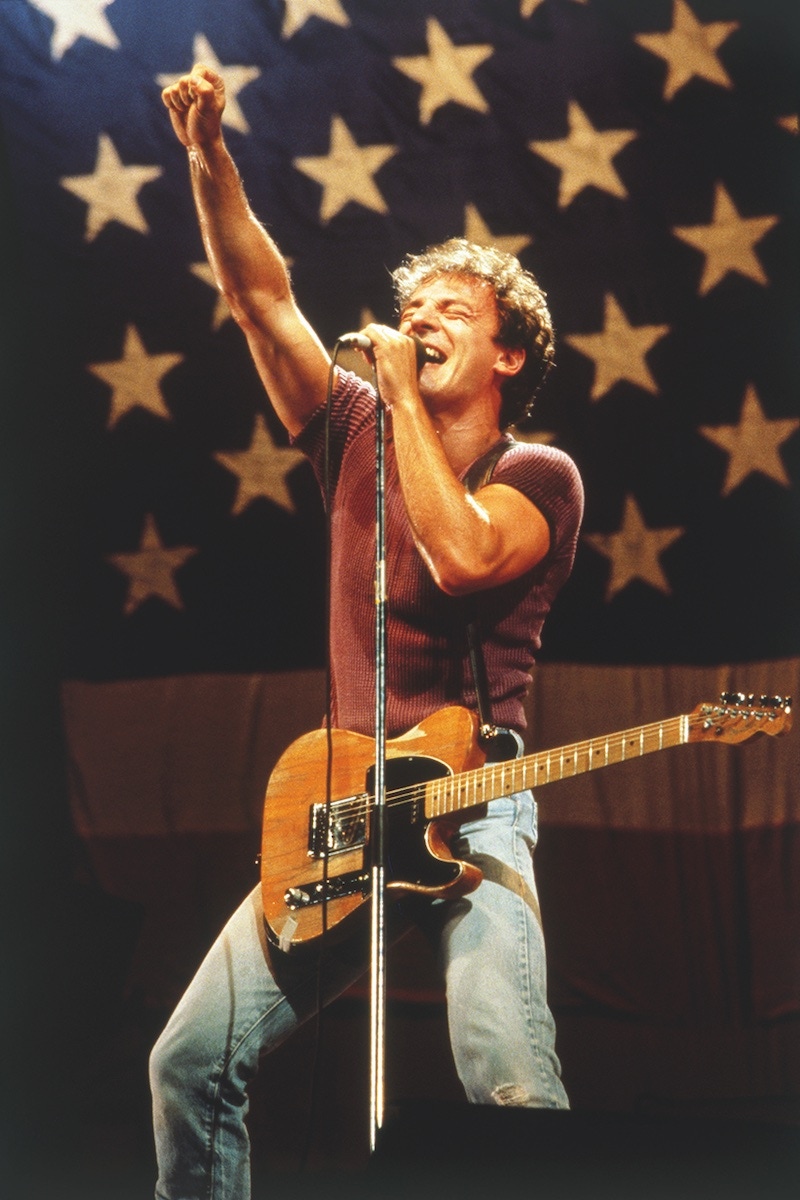

We get him now, of course, but in September 1984, Bruce Springsteen must have felt like the most misunderstood man in America. Every musician wants a hit, but the success of his album Born in the U.S.A., then on its way to selling 15 million copies and reaching far beyond his usual fan base, had provoked reactions he could never have expected. Anyone who listened to the title track with any attention would see that, beside the stadium chant of its chorus, this was a protest song: the blue-collar guy who’s sent off to kill the yellow man returns to find he can’t get a job in the refinery and is left with nowhere to go. What Springsteen hadn’t realised is that most people don’t listen with attention, which is why lately he’d begun to see stars-and-stripes flags at his concerts. Now Ronald Reagan, a right-wing president seeking re-election, was aligning himself with the song and with Bruce himself, talking about how “America’s future... rests in the message of hope” he was giving out.

Poor Bruce. With hindsight, you can understand the mistake Reagan — and half the world — made: that chorus, delivered with pomp and defiance by a man dressed as a redneck, was a misinterpretation waiting to happen. That’s not to reckon with the fact that you’d have to listen all the way to the end (or know your Springsteen) to be sure that there was no happy ending to this hard-times tale. And besides, they had a point: beneath it all, Springsteen was every bit the cheerleader for American values that Reagan was. Both wanted, borrowing a phrase from 30 years on, to ‘make America great again’ — the only difference was the degree of certainty with which they delivered their message. Springsteen said it himself in 2012: “There is a real patriotism underneath the best of my music, but it is a critical, questioning and often angry patriotism. I have spent my life judging the distance between American reality and the American Dream.”

In 2018, under a president who makes Reagan look like The West Wing’s Jed Bartlet, even the most romantic or patriotic U.S. citizen might admit the American Dream is looking more like a mirage. But belief in the land of opportunity, where anyone can achieve anything they like, sustained America for more than two centuries. It was the motor for the can-do attitude, industry and entrepreneurship that revolutionised every aspect of the consumer world. And, perhaps just as importantly, its failures and disappointments inspired a huge proportion of the great American art of the last half-century, Springsteen included.

For a handle on Springsteen, you really need only three albums and their title tracks. Born in the U.S.A. is the most recent of those (although he’s done great work since, from its follow-up, 1987’s Tunnel of Love, to The Ghost of Tom Joad in 1995). The first was Born to Run, from 1975. With the song’s opening line, “In the day we sweat it out in the streets of a runaway American Dream”, it embodies his teenage romance era, the focus on the “cars and girls” with which another sect of non-believers characterise him.

At the time he was 26, so this no-one-understands-me adolescent fantasy was an exercise in nostalgia, as almost all his records would be. Nostalgia is all over pop music, which thrives on mourning and self-consolation and still worships youth above all, but Springsteen’s yearning for some lost Eden isn’t just personal and emotional, it’s political. For all his liberal democrat principles, it makes him deeply conservative. In 1975, he wasn’t thinking on the scale of Reagan’s deluded ambition to turn the clock back to the pride and self-belief of pre-sixties apple-pie America, but the scope of the record meant this was about more than a memory of first love.

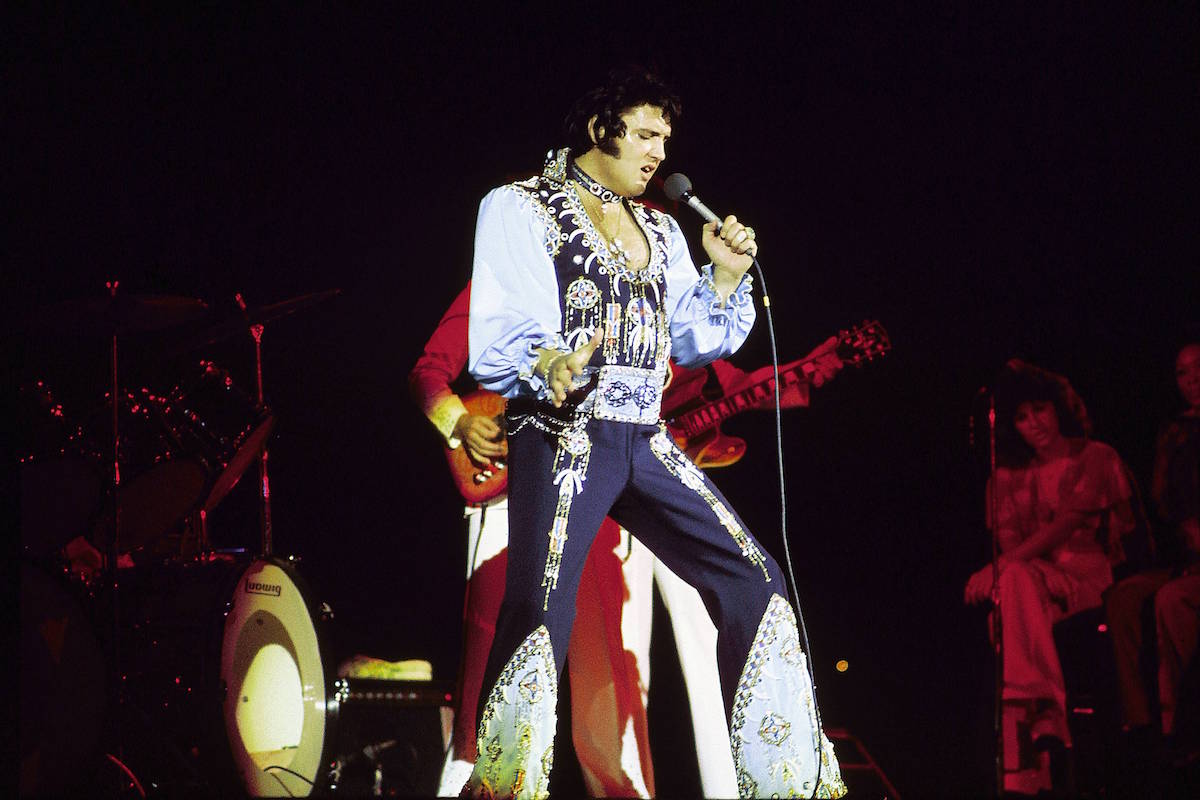

Born to Run is also nostalgic in its musical setting — a rebooting of the sixties’ pop operas of Phil Spector performed with the overwrought spirit of rock ’n’ roll’s first cries of freedom. No one could say Springsteen was pushing any musical envelopes here, or that he would go on to do so at any point in his career; his usual fare is sturdy, conventional rock of the kind that doesn’t usually translate to the U.K.’s admirably perverse palate, and tends to remain massively popular in the more featureless parts of the United States. What makes him great, apart from his delivery, is his understanding of the importance of imagery, significance and romance. On the surface, Born to Run is housed in much the same overblown pastiche style as Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell, released two years later; down below, in its lyrics, however, it’s aiming for something higher. There’s the glamorous rebellion of James Dean but also the tough-times grit of Scorsese’s Mean Streets, the story of two kids who think they’re too big for their small town, but also the idea, incarnate in that first line, that even American dreams can turn sour.

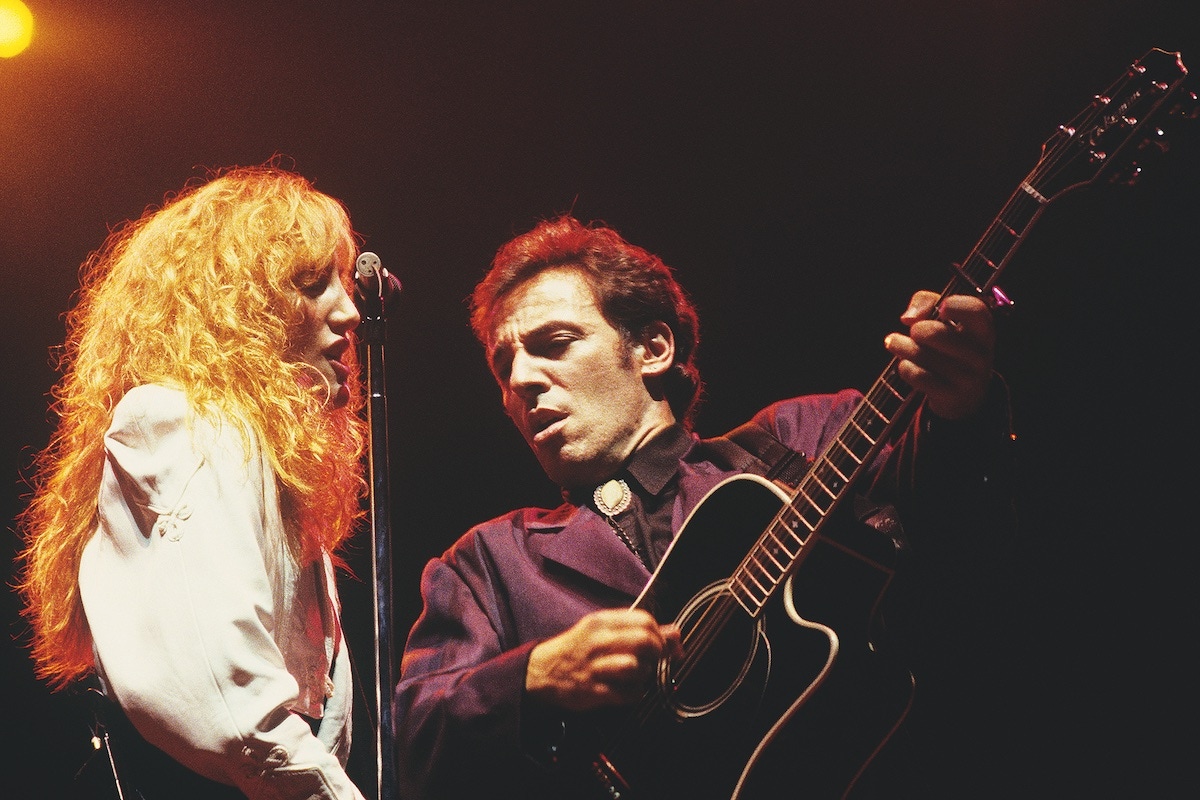

That idea was only amplified on the second of his key releases, 1980’s The River. This double album ranged wide (lead single Hungry Heart was a sledgehammer-catchy rocker he originally wrote for The Ramones), but the epic title track was its essence. For this, he pulled the focus wider, to the decline of America’s industrial power, lowered the tempo to stately balladry, and eased the tone from melodramatic to melancholic. After the introduction of a soul-razing harmonica howl, it tells the story of a couple who obediently trudge through a just-about-managing cycle of birth, marriage and living death, haunted by their one experience of freedom, swimming together in the river outside town. The song’s key line, “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?”, could be the most Springsteen thing he ever wrote. Rather than Meat Loaf and Phil Spector, this is Tennessee Williams and John Updike, a portrait of those who don’t get to live the American Dream that only serves to reinforce it as an ideal.

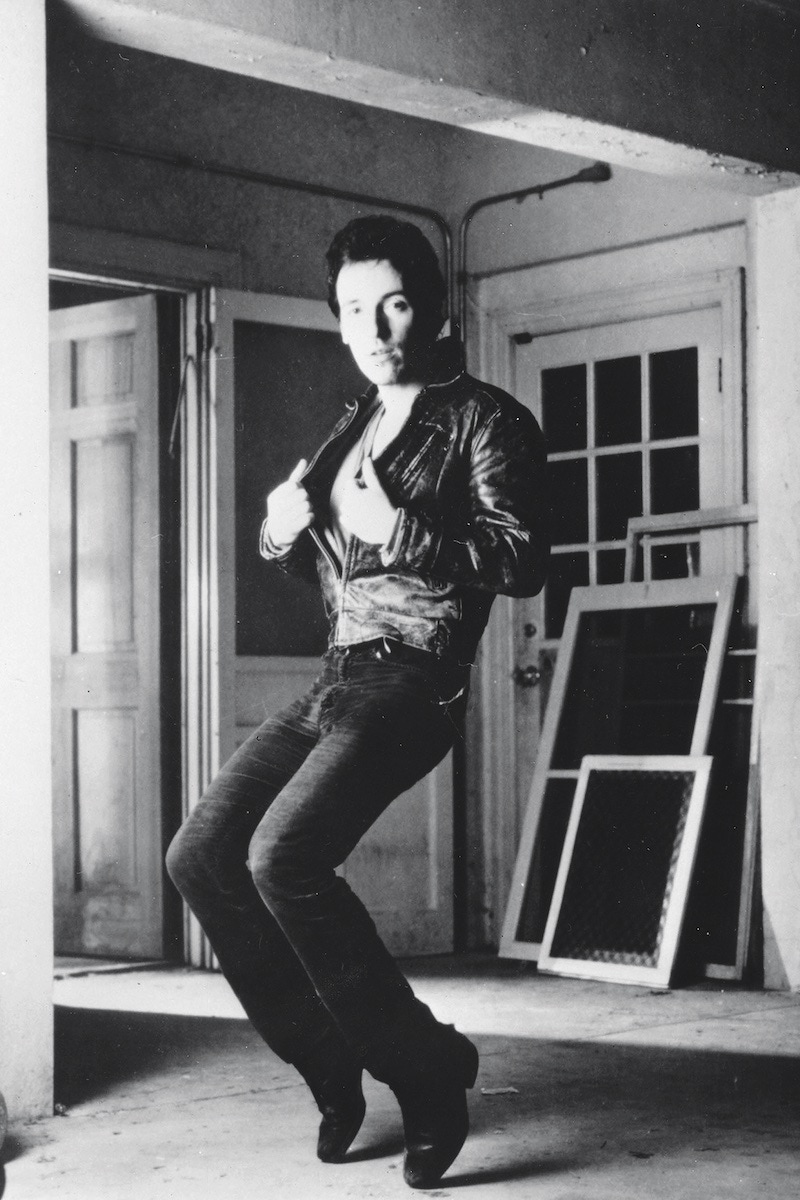

By then, the lantern-jawed New Jersey boy was not only sounding more like himself but was looking it, too, dressing to suit the message. He’d lost the leather jacket of the Born to Run era, paring back to the checked workshirt as if he’d moved from big-city N.Y.C. to smalltown Midwest, taking the cross-country pioneer trail like a John Steinbeck character. This evolution from local hero to American Everyman was at least partly down to his manager, Jon Landau. As a journalist, Landau had written the legendary 1974 review that contained the line, “I saw rock and roll future, and its name is Bruce Springsteen”.

Though Springsteen’s record company used it to sell their kid as the next big thing, what Landau really meant was that he’d seen the vehicle for preserving his own romantic idea of rock ’n’ roll’s past. Once he began to guide Springsteen’s career, he helped remodel his protégé as his own personal American Dream, telling him what to wear, what to read and how to talk, and urging him to keep his music direct and simple.

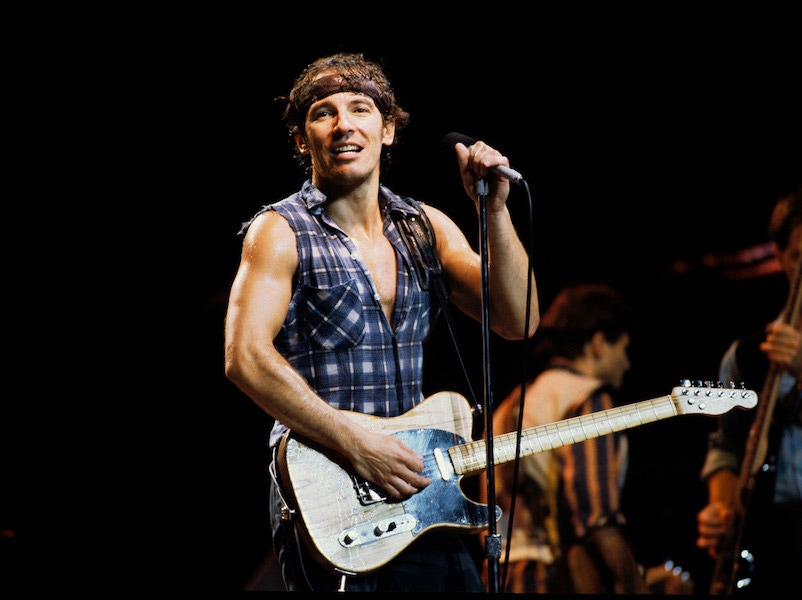

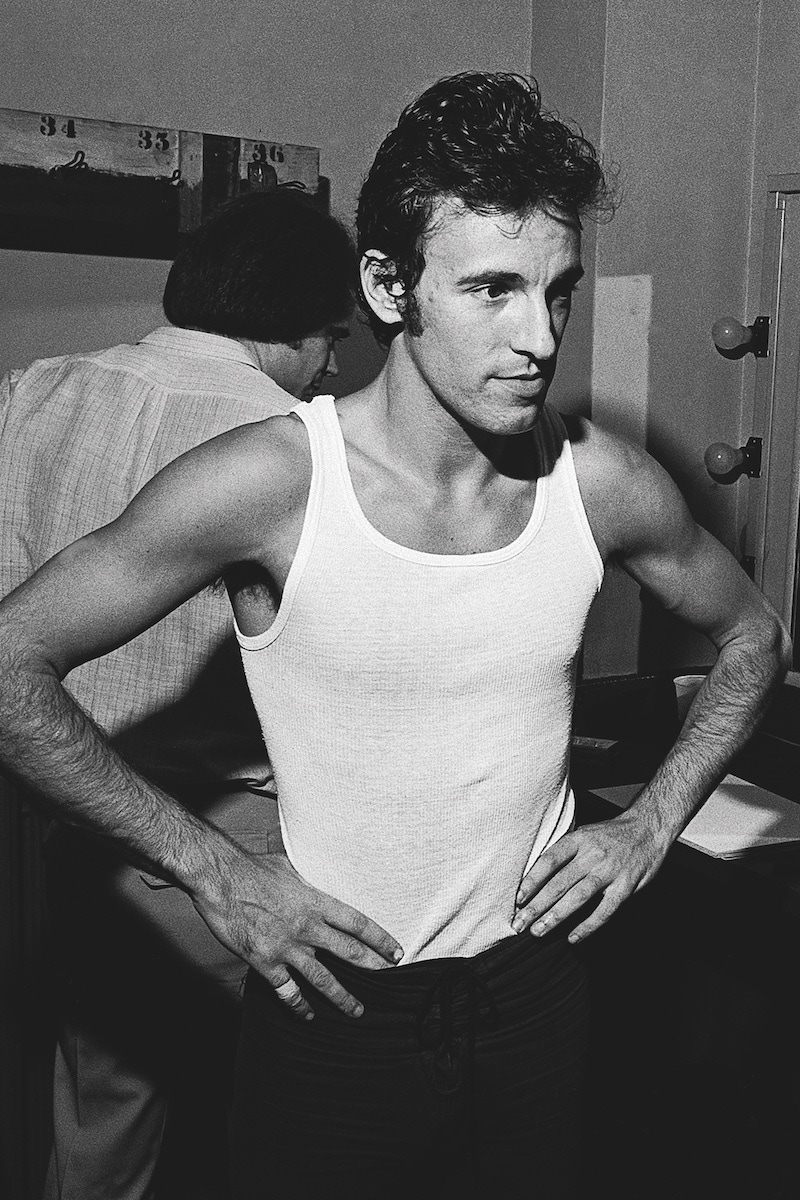

By Born in the U.S.A., the check shirt had been reduced to a cap-sleeved white T-shirt, stretched over newly pumped-up biceps, and Springsteen’s workwear combinations had become more than clothes. The jeans, plaid, Frye biker boots and cut-off denim jacket were the uniform of smalltown America, but they were also his costume. Springsteen, in the words of his biographer, Peter Ames Carlin, gave this workaday look “a mystique that seemed to capture the essence of America’s shattered dreams”. Through sheer consistency and association with his image, his anti-fashion gesture became fashion.

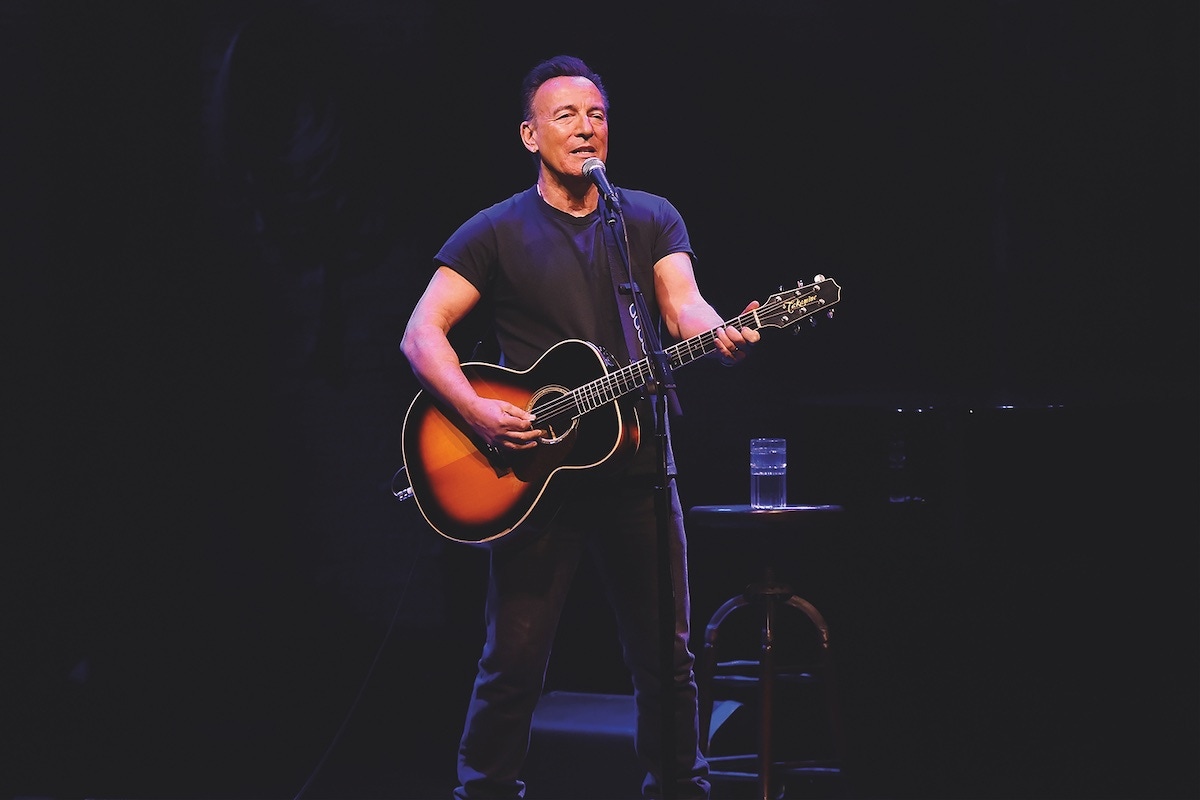

If, these days, as Carlin says, “his shirts are custom-designed and hand-stitched, just as his new guitars are distressed to give them that classic look”, that’s no longer the point. Springsteen’s music and image are now to be seen in the same spirit as another great American dreamer, Ralph Lauren, who offers luxe versions of work clothes that create an idealised version of the American life — the weekend glamping rather than the month backpacking. It’s no coincidence that Bruce’s daughter, Jessica, is a brand ambassador for Polo Ralph Lauren, her career as a showjumper covering the preppy blazer-and-chinos side of the brand while dad takes care of the urban-cowboy sector. Indeed, Bruce Springsteen and Ralph Lauren are now so linked that on the opening night of Springsteen’s run of solo shows on Broadway in October last year, the afterparty was hosted at Lauren’s Polo Bar.

The connection may go deeper still. For those keen to unpick the layers of invention and argue over the authenticity, they are equally hollow, unoriginal and reactionary. But no one can deny their straight, clear-eyed positivity. As Vanity Fair once put it, Ralph Lauren’s clothes are “the best advertisements for America that you could ask for”. Likewise, Springsteen, for all his tales of broken promise and disappointment, is its best advertiser. Through all the melodrama, misery and protest, he still believes in America and he still has hope for its future — even if, to quote another of his songs, it’s just dancing in the dark.

This article originally appeared in Issue 60 of The Rake.