A DANDY LION

He was only alive for seven of the 50 years the Stones have been rolling. But founder Brian Jones was the defining force of the band during what would prove to be, both musically and sartorially, their most potent period

It's one of human nature's more morbid foibles that we glamorise premature death. Alexander the Great famously struck a pact with the gods that saw him suffer a young but glorious demise: 'It is a lovely thing to live with courage and to die leaving behind an everlasting renown,' he supposedly asserted, presumably in a spot of downtime between crucifying insurgents, catapulting boulders into Persian fortresses and dying of fever aged 32. It's possible the Macedonian marauder was borrowing, here, from his paragon of choice: Achilles, who, the blood seeping from a spear wound in his famously vulnerable heel as he clambered over the gates of Troy, also reputedly thanked the Fates for sparing him a life of protracted obscurity.

If untimely demise was fashionable among warriors in the ancient world, more recently it has been the preserve of foppish creatives: poets during the romantic era (John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron died at the ages of 25, 29 and 36, respectively) and, of course, rock stars in the modern age. When it comes to the latter, 27 is the number that has numerology buffs dribbling all over their abacuses, with Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain and, most recently, Amy Winehouse all bowing out three years shy of becoming tricenarians.

Croaking in their prime clearly cements a rock star's status in pop-culture mythology, and one of the reasons for this is people's assumption that, as with the cases of Alexander and Achilles, there's some kind of willingness - consent, even - involved. Clearly there was in the case of Cobain, but the others have fallen to death-by-revelry - which, despite there being little discernible glamour in heroin, vomit-choking or liver failure, is often seen as some kind of noble concession to a greater artistic good. Especially in the callow eyes of those still young enough to have delusions of their own immortality, a flower choosing to be plucked at the apex of its own bloom to spare it the ignominy of withering in front of its admirers is seen as being wholly commendable.

The death of Brian Jones, as ruthlessly hedonistic as he may have been, entirely undermined any such absurd notions of Byronic legend, of pacts with the artistic gods. There remain clashing theories about how the Rolling Stones' founding guitarist was found dead at the bottom of a swimming pool (at a home previously owned by the author of Winnie-the- Pooh books, A. A. Milne, curiously enough) at the entirely coincidental age of 27. 'Death by misadventure' was how the coroner's report described it, blaming 'immersion in fresh water under the influence of drugs and alcohol'. Some still insist that foul play was involved, pointing the finger at his builder, his minder and even a Voodoo priest in a small North African village (Jones was convinced that a curse was put on him while he was producing Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Panat Joujouka in Morocco in 1968).

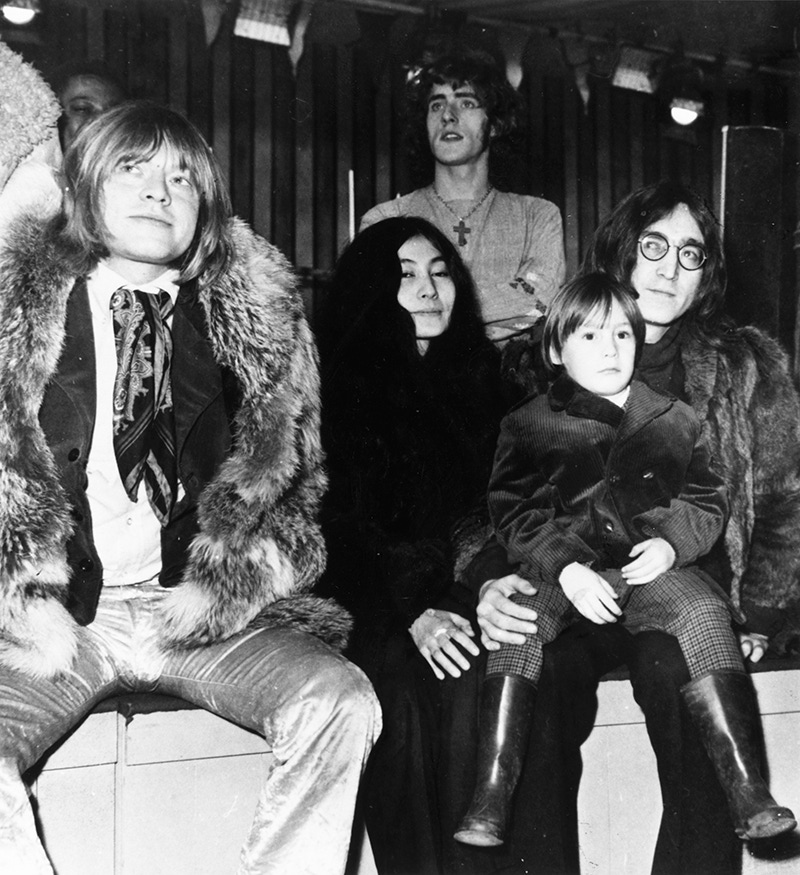

Another commonly pedalled theory is that he took his own life. Jones had been ejected from the Stones three weeks previously, having often been absent from, or inept at, recording sessions due to his drug habit. He had also recently lost the sublimely beautiful Anita Pallenberg to Keith Richards (plus, according to some insiders, another lover to Mick Jagger), just at the point when that duo's talent for co-writing catchy rock ditties had diminished to zero Jones's own role within the band he had formed seven years previously.

Suicide seems unlikely, though. Many who knew him (including his father) report that he was in a regenerative state of mind at the time of his demise, and bursting with enthusiasm over new musical projects on the horizon. All that is certain is that there is nothing romantic, or edifying or artistically ordained about the death of Brian Jones. This was a case of a young man bursting with musical innovation and charisma being snuffed out at the height of his creative powers. 'Tragic' barely scratches the surface.

Jones grew up in Cheltenham, a middle-England spa town in the Cotswolds. The son of an aeronautical engineer and a piano teacher, he was devoted to music to the point of obsession by his mid-teens. It was the fizzing, hard-bop jazz of Cannonball Adderley that prompted him to nag his parents to buy him a saxophone aged 15; his first guitar followed on his 17th birthday. The night that Jones' musical legacy was set in motion in came in 1961, when he went to see Alexis Korner - the founder of British blues - play at Cheltenham Town Hall. Had Jones never attended this gig, the Stones would never have happened.

Korner's performance, and a chance meeting with him afterwards, impelled him to leave his sleepy hometown for the British capital, just as that city was about to give birth to a cultural phenomenon. It was a good few miles away from the West End glitz that won the hearts of Sixties London swingers, in a grungy, downbeat jazz club in Ealing, that Jones - playing as 'Elmo Lewis' - was introduced to a couple of aspiring rocker types from Kent, Messrs Jagger and Richards.

It's difficult to say just how fervently Jones would blench were he still alive in 2013, well into his 70s, standing at the back of Wembley Stadium watching the latter-day Rolling Stones play a repertoire of mostly boorish, clunky rock songs to middle-aged lighter-wavers at the start of their muted 50th- anniversary celebration tour. The same band - in a manner of speaking, anyway - that he formed, recruited and named at its outset and defined in its heyday. Easily the most gifted Stone in terms of performance and sonic innovation, he was probably Britain's first slide guitarist (the exquisite bottleneck accompaniments on 'Little Red Rooster' is to the 'Jumpin' Jack Flash' riff as cashmere is to sackcloth). Also highly accomplished on keyboards and harmonica, his musical curiosity and ability

to turn his hand to anything that had an auditory effect gave early Stones hits their distinctiveness, catchiness and durability - think the sitar on 'Mother's Little Helper' and 'Paint It, Black'; the Mexican marimba in 'Under My Thumb'; the cello on 'Ruby Tuesday'; the Mellotron on 'She's a Rainbow'. Feeling excluded by his not being a songwriter, he responded by tinkering with Jagger and Richards' no-frills rock blueprints, tireless in his quest to make them richer, more idiosyncratic.

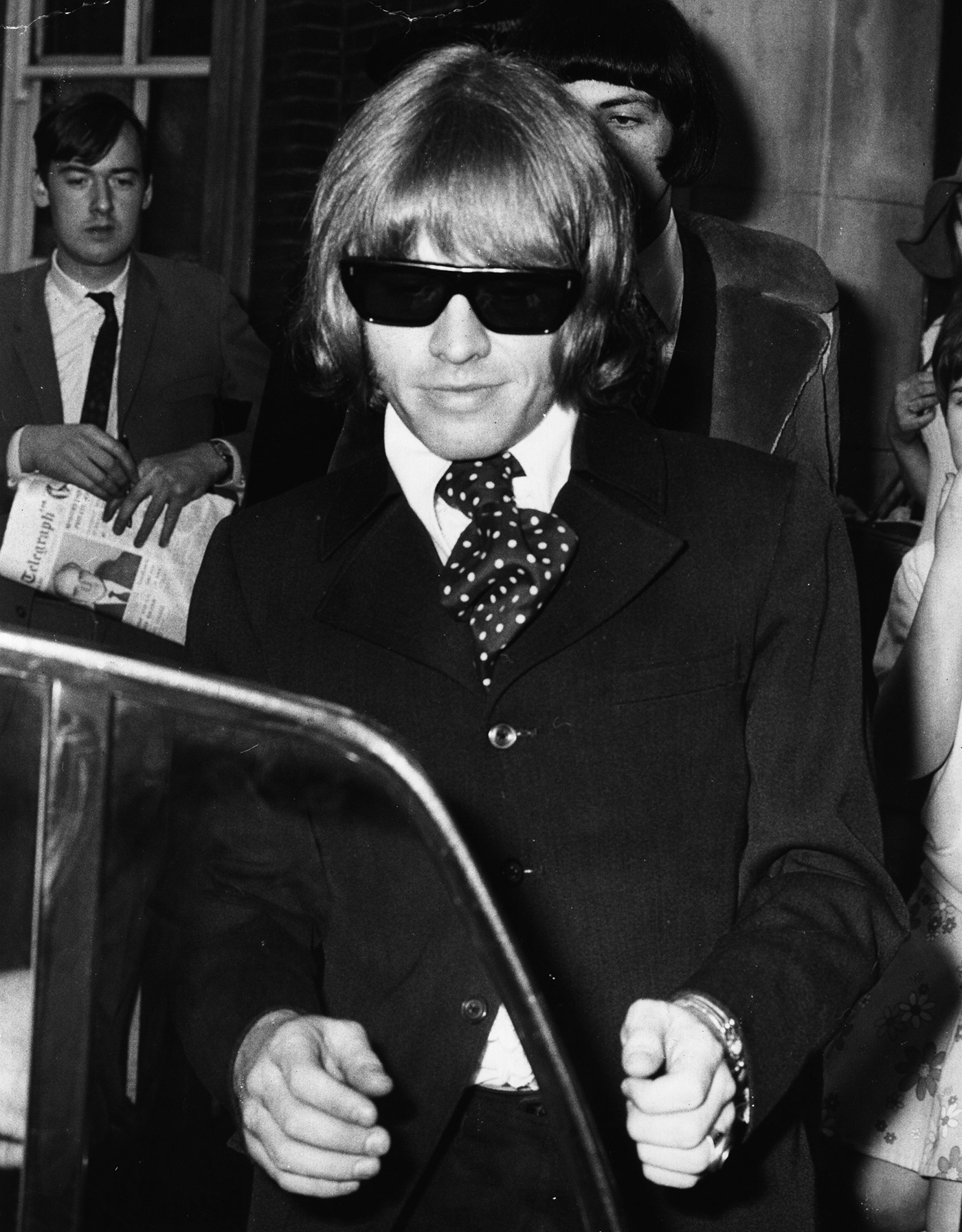

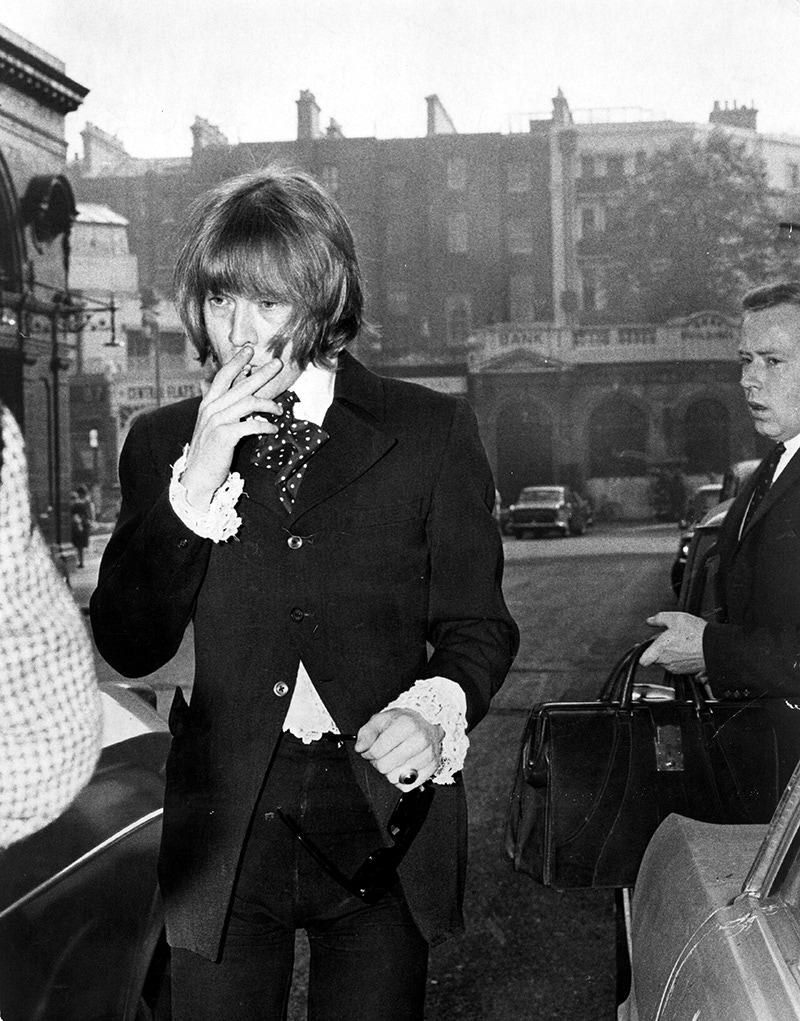

And, as the photos on these pages testify, this pathological brio extended to Jones' wardrobe, too. London's unofficial Peacock Laureate, he revelled in the bizarre and unorthodox, and was successful in an industry which afforded him the means to delve eccentric gems from the city's boutiques such as Granny Takes a Trip, Hung on You and Dandie Fashions. 'Jones would parade the streets of London wearing a Victorian lace shirt, floppy turn-of-the-century hat, Edwardian velvet frock coat, multi-coloured suede boots, accessorised scarves hanging from his neck, waist and legs along with lots of antique Berber jewellery,' writes one of his many biographers Geoffrey Giuliano.Jeremy Reed-author of Brian Jones: The Last Decadent - is one of many to compare him to Oscar Wilde.

Indeed, there's much that put him in the tradition of great British decadents: his brushes with sartorial androgyny (some reports suggest he based his look on Françoise Hardy); the appetite for mind-benders, notably marijuana, LSD and alcohol; his love of literature; the expensively acquired brogue and vocabulary. And, of course, his heavily notched bedpost. Thought to be the father of at least six children, Jones' notoriety on that front began during his teens, when his 14-year-old girlfriend, a Cheltenham schoolgirl, became pregnant. (The same year, a married woman fell pregnant by him during a one- night stand following a gig in Guildford; Jones went to his grave not knowing of this offspring's existence.) He only got started on the models (Pallenberg, Amanda Lear, Suki Potier) once the Stones took off, of course. Not bad for a former bus conductor.

He also suffered from crippling mental frailty. Petulant, ultra-sensitive and borderline paranoid when it came to establishment figures, Jones' substance abuse - '[He] lived on a higher planet of decadence than anyone I would ever meet,' as The Who guitarist Pete Townshend once said - probably was, at least at times, induced by a need to self-medicate. That said, 'He had little patience with authority, convention and tradition,' as Canon Hugh Evan Hopkins put it in a eulogy that continued in a vein of sanctimonious pique. 'In this he was typical of many of his generation who have come to see in the Stones an expression of their whole attitude to life. Much that this ancient church has stood for in 900 years seems totally irrelevant to them.'

Nearly half a century on, the influence and legacy of the original Stone - the founding and most creatively exuberant Stone; the guy who may have stopped them gathering unwieldy clumps of moss at so many points of their frankly erratic career - would these days only seem so insidious to the most prudish and blinkered of cultural observers.