Absolute Power: Gene Hackman

To close our three part series exploring the work of some of the most rakish American actors of all time, we felt it only appropriate to end on an individual whose performances are understated, though not underpowered.

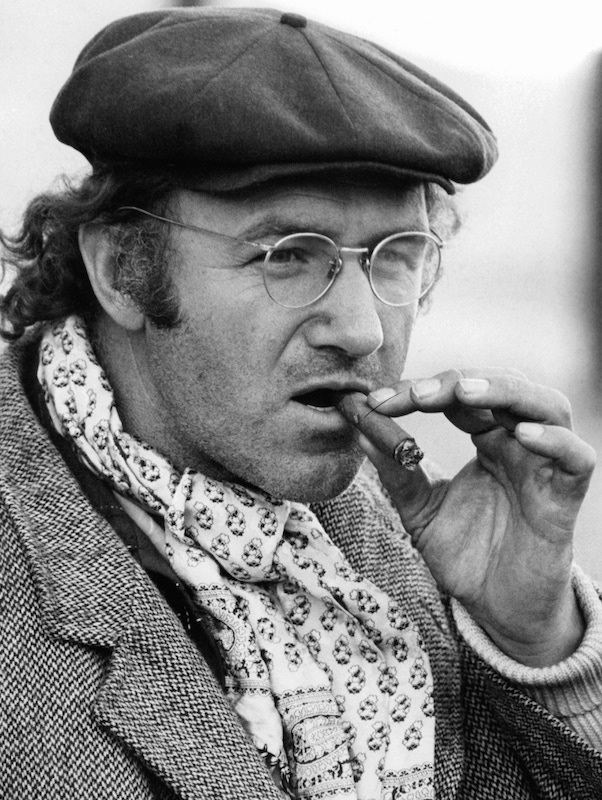

In the seventies, a cubist decade when the likes of Al Pacino and Jack Nicholson reinterpreted the face of the Hollywood lead, Gene Hackman was a droll ploughman of nonfiction poetry: doughty, thin-eyed, thinner-haired, a screech-red enforcer in horse-high grass. His voice, that famous voice, has dropped octaves over the years, from reedy tenor to grit-paved bass, but he’s always had that little laugh, an ambiguous punctuation mark of comic menace.

Like many of his peers, his screen personae were forged by his upbringing. Hackman’s father abandoned his family with no more than a wave to his 13-year-old son, who was playing in the street at the time (Hackman has since said the moment seeded an actor's sensitivity to the significance of small gestures). At 16 he lied about his age to enlist in the Marines and was stationed in China, Hawaii and Japan before he was kicked out for fighting. In 1962, his mother died as a result of a fire she accidentally started by smoking.

Hackman channelled this emotional repertoire, along with his idolisation of James Cagney and Errol Flynn, into the Pasadena Playhouse, where he met a young Dustin Hoffman. The two shared a flat and shot the breeze with another aspiring actor, Robert Duvall. According to a Vanity Fair piece on the trio, they would pretend to beat each other up to attract women and play drums on the roof as a tribute to Marlon Brando. Sometimes after a film or dinner together, Hackman would excuse himself to find a bar to start a fight in: "There's a kind of catharsis about it. I don't want to get hit, but I don't like to take any shit." Hackman worked as a hotel doorman to make ends meet and was voted “least likely to succeed” at school, but he, Hoffman and Duvall would rack up nineteen Oscar nominations and five wins between them.

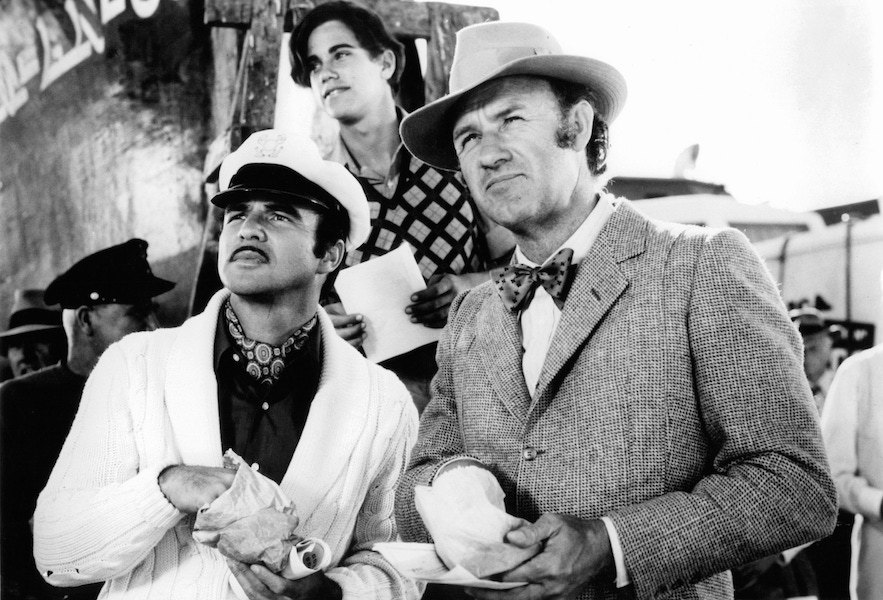

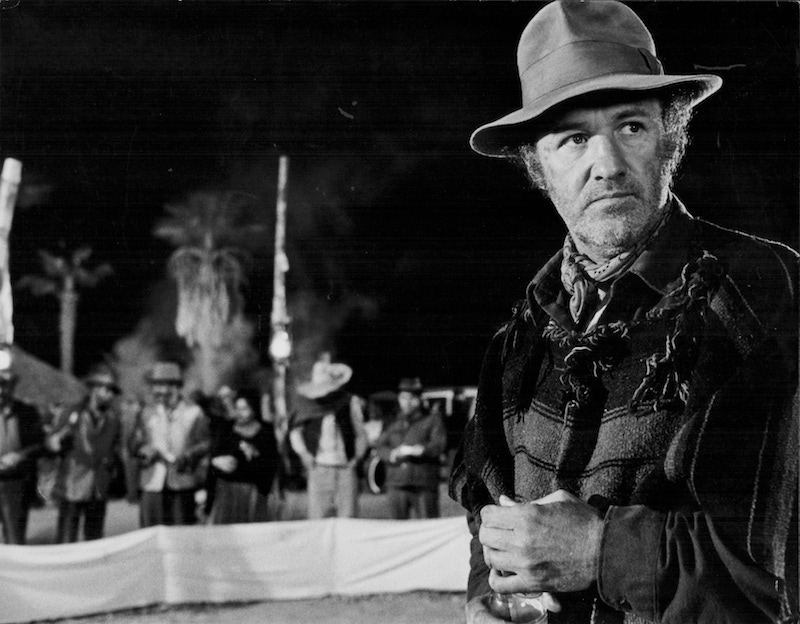

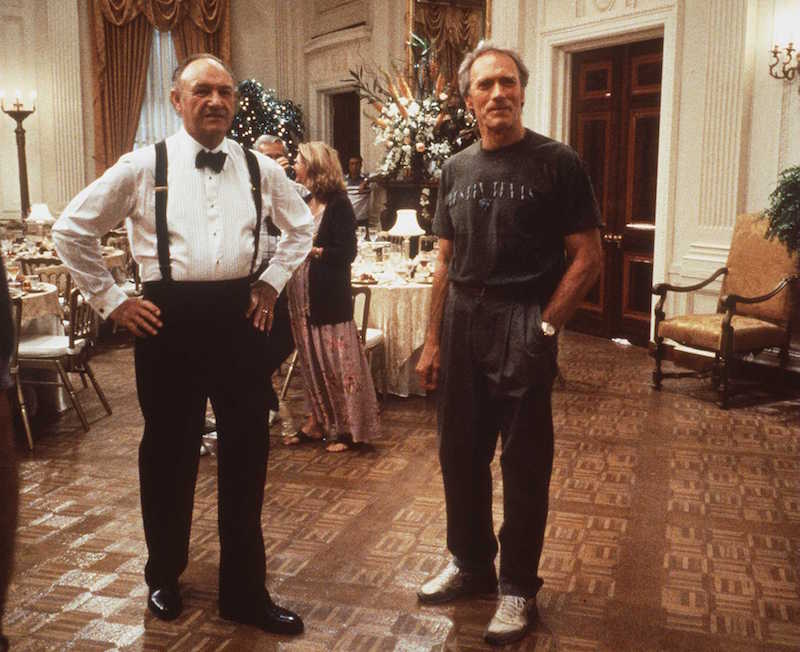

"He’s always had that little laugh, an ambiguous punctuation mark of comic menace."As a Grantland profile put it, for over three decades audiences paid to watch Hackman take charge: he “taught Redford how to ski, DiCaprio how to shoot, and Keanu how to play quarterback”. But he tempered bravado with wit and vulnerability. Breakout macho roles as Buck Burrow in Bonnie and Clyde or Popeye Doyle in The French Connection (for which Hackman prepared by going on drug raids with Eddie Egan, the real-life inspiration for Doyle, and won his first Oscar) belies the subtler self-doubt of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (a masterclass in small gestures) and Palme d’Or winner Scarecrow (Hackman’s personal favourite of his films). This duality seeps beyond the screen: the bashful introvert on the Oscar stage is a photo negative to the kind of actor on set who, according to Hoffman, would “throw a director from one end of the room to the other”. His earthy, bitter gravitas doesn’t create anti-heroes so much as thwarted anti-villains: a sheriff-turned-FBI agent in Mississippi Burning, sheriff-turned-gunfighter Little Bill in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (another Oscar) and a usurped submarine captain in Crimson Tide. The latter – one of the most intelligent, morally complex action films ever – smuggles in a neo-Shakespearean character-tussle with Denzel Washington, whose mutinous “I do not recognise your authority” is the most creative kind of baton-wrest from one generation of male lead to the next. Weighty thrillers like Enemy of the State preceded his perfect swansong in 2001 as Royal Tenenbaum, a glorious mix of ego, duplicity and charm and the most rakish patriarch in modern cinema. Retirement hasn’t diluted Hackman’s approach to life. In 2001, he punched a driver who overtook him; he recently slapped a homeless man who threatened his wife. A love of fast cars has been a leitmotif: in the seventies he drove an open-wheeled Formula Ford in the Sports Car Club of America races. In 1983, he took a Dan Gurney Team Toyota to the 24 Hours of Daytona Endurance Race, and he has won the Long Beach Grand Prix Celebrity Race. Car chases bookend his films, from The French Connection's opera of choreographed chaos to The Royal Tenenbaums' go-kart race with his grandchildren. Hackman told GQ he’d love to have played Robert Jordan from Hemingway’s For Whom The Bell Tolls or The Count of Monte Cristo’s Edmond Dantès, tough-sensitive adventurers for the late-life novelist in him. Rumour has it he was even first choice for Hannibal Lecter - an exhilarating prospect. But Hackman seems at peace with his canon and focused on the present: he doesn't watch his own films, told Larry King he doesn’t have any future film projects, and suggests his epitaph would be the modest “he tried”. All three of the actors in this series – De Niro, Nicholson, Hackman – shower cinema with expansions from inside themselves, as if from dreams of rain. Now 86, Hackman has contoured an iron-butter charisma in predawn after-darkness, flogged half-insane by his own standards. His reputation remains foam-white, his filmography a fireless jumble of sabres in ground coral. We absolutely recognise his authority.