Celluloid Heroes: Giorgio Armani In Cinema

Giorgio Armani has continued to push the sartorial boundaries and redefine how men and women should dress — all while staying true to himself.

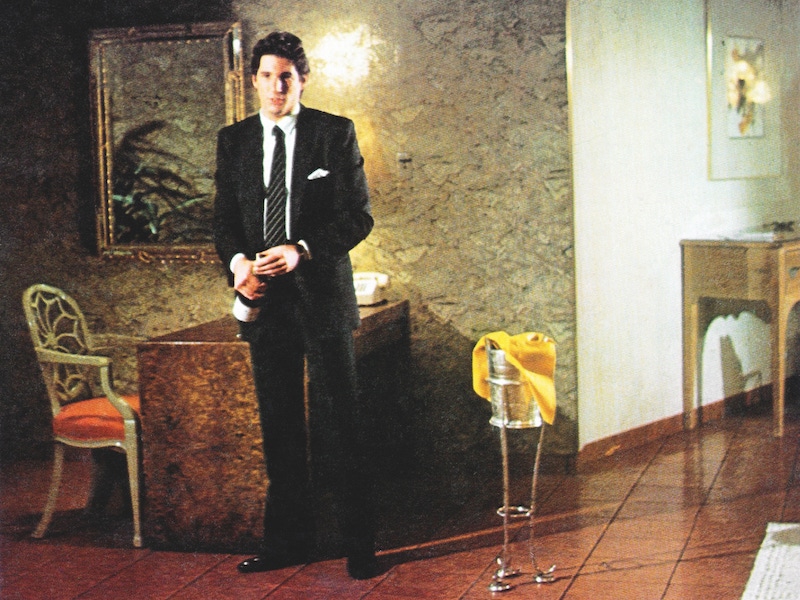

Even before the film American Gigolo had projected a single frame onto a single cinema screen, the world had already become seduced by the revolutionary vision of designer Giorgio Armani. Through engineering the ineffable arousal, the visceral tension, between masculinity and sensuality encoded into the movie’s poster and various publicity stills starring then-newcomer Richard Gere, Armani had already penetrated the consumer consciousness with a power that was nothing less than all-consuming: one that would define the way men dressed for the next four decades. He simultaneously revolutionised the methodology of image dissemination, transforming the silver screen and its denizens into his catwalk and his models.

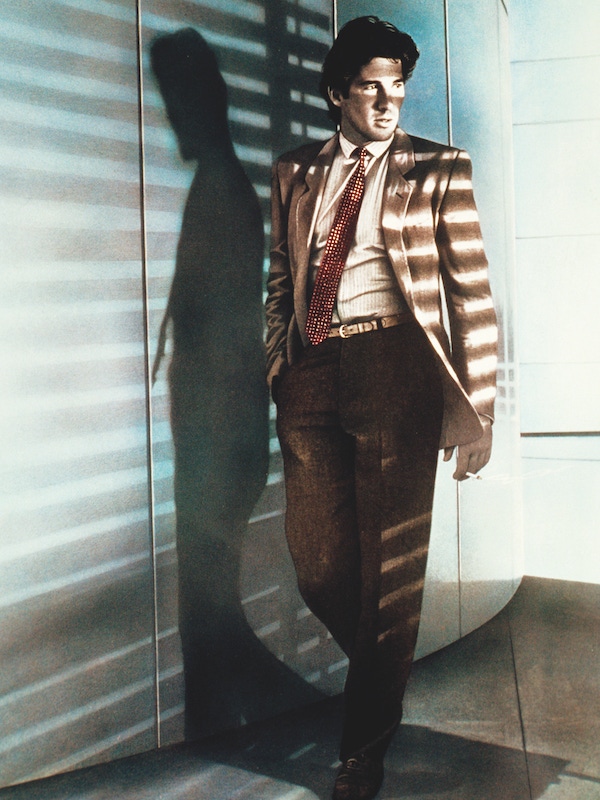

The poster projected the image of the modern-day dandy, a man who stood in sharp contrast to the prevailing deracination of formality from street wear in 1975. Gere wore, of all things, a tie and sport coat. But it was the way he wore them: with rakish dégagé, combined with the sensual élan of the clothes themselves that unleashed a renewed relevance and an all-new sexuality for formal clothes and classic style.

In the poster, Gere strides like a predatory cat, demonstrating the fluid equanimity of his Armani clothing. He is defined in motion by their deconstructed softness, transubstantiated in the commingling of flesh and fabric into a work of Italian modernism as groundbreaking as futurist Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space.

"Armani transformed the jacket from a male uniform into a mythological garment."His jacket is an apparent contradiction, simultaneously offering the cocksure shoulder and virile lapel of Milanese tailoring combined with the totally deconstructed body of the Neapolitan style — evoking strength bordering on arrogance but providing a liberation of form and a soft sensuality. In this one fell stroke, Armani transformed the jacket from a male uniform into a mythological garment, a lightning rod for contemporary culture, prophesising the new era of male body consciousness and burgeoning peacockism. Gere’s clothes foresaw and would be the first expression of the return of the suit as a power symbol that would reach its apogee in the ’90s: the reinterpretation of masculine codes towards a new modernism, the reinvention of fashion’s chromatic language and the birth of the 20th century’s most significant designer, Giorgio Armani. Interestingly, the thing that drove Armani — the cynosure of his philosophy regarding clothes — was the same thing that drove style icons like the Duke of Windsor or Fred Astaire, and legendary tailors like Frederick Scholte or Vincenzo Attolini: the concept of liberation. Over the greater part of its existence, men’s clothing had conspired to trap its wearer, the practical benefit to this being the transformation of an anaemic body into Herculean form through the use of padding and other structural trappings. The root of this constricting palimpsest is found in military dress, in which an Adonis-esque form is built upon its wearer regardless of the underlying reality. Said the Duke of Windsor, “It was my impulse… to rip off my tie, loosen my collar and roll up my sleeves.” His frustration with the physically hegemonic imprisonment of his clothes led Edward VIII, through collaboration with maverick tailor Frederick Scholte, to give birth to the British drape, a sartorial liberation which saw cloth flow over the human form as if poured. Similarly, in 1930, tailor Vincenzo Attolini and dandy ne plus ultra Gennaro Rubinacci created the Neapolitan jacket to better fit the needs of their warm climate. They stripped the jacket to its barest essentials, tossing aside shoulder pads, horsehair and interlinings to create coats that were as light as the winds over Vesuvius.

In Martin Scorsese’s documentary Made in Milan (1990), Giorgio Armani demonstrates the fundamental mimetic gesture related to his philosophy for men’s clothes. Through a series of dissolves, he tears away the padding, the canvas, the lining. In the script for the film, he states: “I wanted to find a way to make and wear clothes for a time that was less formal but still yearned for style. I had to start from the foundation. And for me, the foundation was the jacket. Taking away the structure of a man’s jacket was a way of loosening the form. The style has to be surreptitious. Not well pressed. Not perfect. Not rigid… My jackets change all the time… But I always want them to look as if they had hung in your closet for years. Like something that you’d owned forever.”

Through this one revolutionary gesture, Armani democratised the deconstructed style that the world’s most elegant men could previously find only at the most elite tailors. Says Armani, “I decided to get rid of all those ‘structures’ in jackets. This was what was making everyone look identical. I experimented with letting the clothing fall over a man’s body, bringing attention to this so-called ‘defect’. The idea was to deconstruct the suit, providing more freedom and movement. I thought this was essential, allowing men a more personal and real look.”

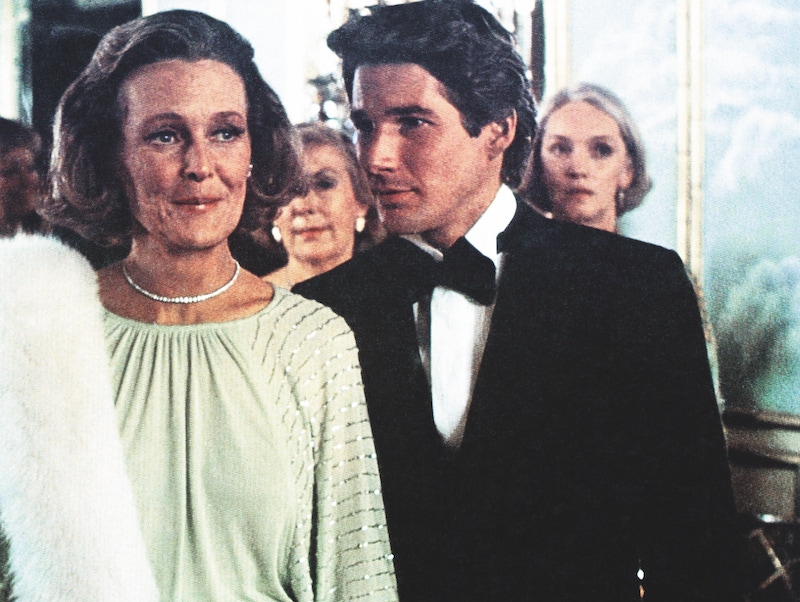

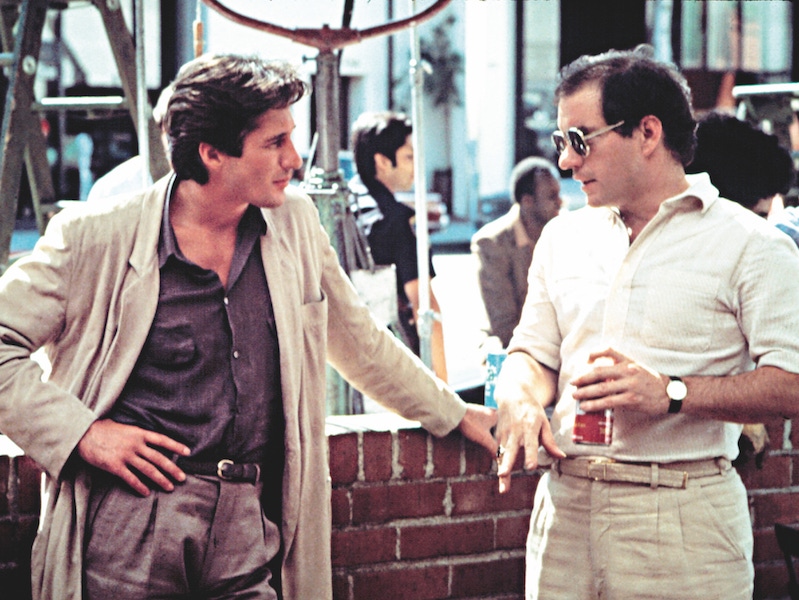

Now that he had the philosophy, one so saliently tapped into the zeitgeist of transforming male body culture, Armani had to find a way to project his vision into the world. He found the perfect vehicle for his expression in cinema. More than any other fashion designer, Giorgio Armani utilised the silver screen to project the message of his revolutionary vision for men’s fashion. His first and most iconic vehicle American Gigolo, directed by Paul Schrader — previously a writer best known for penning the screenplay for Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver — made Armani an instant legend and compelled the movie’s leading man, Richard Gere, to state: “Who’s acting in this scene, me or the jacket?” The movie — ostensibly about the fall from grace of Los Angeles’s most seductive gigolo — was more successful as a cinematic runway for Armani than as a cautionary tale. Onscreen, Armani unveiled the modern-day dandy, now clad in soft, unstructured clothing to complement his gym-toned physique.

But just as Armani ushered in a revolution in form, he also introduced an all-new vocabulary for colour. Unlike the florid palette the term ‘gigolo’ traditionally conjures up, Gere’s clothing — some 30 suits and jackets and a veritably Gatsbyian orgy of shirts and ties — expresses Armani’s mastery of subtly modulated monochromatic hues, and expresses a sense of minimalist reductionism as pronounced as George ‘Beau’ Brummell’s when he ushered in the era of the modern Regency dandy by paring away extraneous artifice and the rather unctuous overuse of colour.

As Suzy Menkes put it, “His principles are akin to the minimalist ideas of the Bauhaus: design free from meaningless ornament.” Says Armani of his fascination for this stone-hued language, which he referred to as the “colours of dawn and dusk”, “I think I succeeded in reintroducing the concept of sobriety into style.” When asked of his inspiration, he defers to his fondness of screen heroes like Cary Grant — the cinematic master of monochromatic style. The one example that instantly comes to mind when Grant’s name is conjured up is North by Northwest, in which he wears — in every single scene — the same grey, single-breasted suit, a white shirt and a grey tie.

On deeper exploration, it seems that Armani’s colour palette was also inspired by his mother’s innate sense of sobriety. He explains, “Before the war, she would wear a lot of grey. Her clothes were simple styles… She never gave way to exaggeration… She was a woman who had succeeded in matching her style to her temperament, rejecting artificiality, ostentation and caricatures.”

"The American gigolo — the character, that is — created by Armani represented a fracture in cultural progression."He also once stated: “I am known as the stylist without colour, the inventor of ‘greige’, a cross between grey and beige. I love these neutral tones, they are calm, serene. They provide a background on which anyone can express him- or herself.” However, the truth is that Armani’s colours are often created through the juxtapositioning of multiple shades of a similar hue, similar to the technique used by the legendary Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko. As Lauren Hutton would gush, “He takes seven colours to make just one.” The American gigolo — the character, that is — created by Armani represented a fracture in cultural progression. In the context of the Swinging Sixties and the disco-inflected ’70s, it was a revolutionary swingback to reductionist, classic style with the added comfort and personalisation offered by totally unconstructed clothing. In other words, Armani’s entrance into the world via the medium of American Gigolo was the single most important moment in late-20th-century men’s fashion, heralding a new era that was simultaneously the liberation from the oppression of suiting as a uniform and the introduction of a profoundly seductive, new, core dandy code that could instantly be accessed at boutiques and shops in every metropolis in the world. Significantly, his unstructured approach eliminated one of the major pitfalls in men’s prêt-a-porter — the fusing of fabric with interlining. Because of this, Armani clothes are unique in fashion for becoming more beautiful the more often they are worn. Through American Gigolo, Armani gave men the world over permission to dress entirely for themselves. The most seductive scene in the movie happens not between Gere and Lauren Hutton, but between Gere and his clothes. We see him dancing barechested and alone, a modern-day Narcissus completely immersed in the autoerotic selection and accessorising of his (mostly) Armani clothes. While Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby unveiled his cavalcade of haberdashery finery for his object of his desire, Daisy Buchanan, here Gere arrays his sartorial riches solely for himself. We are plunged, through his eye, into a sea of Armani’s signature tactility composed of camel hair, alpaca, crepe — fluid, soft sensual fabrics that compel us in, and which seem selected both for their look as well as where they fall on the scale of Young’s modulus of elasticity. And, through his eyes, we recognise the complexity of contrasting and complementing hues in each article of clothing. The garment that best expresses these new-world concepts is Gere’s camel-hair coat. Unlike the traditionally bulky double-breasted model with turnback cuffs originated by British polo players to wear between chukkas, Armani’s take is single-breasted and of minimalist purity, resulting in a highly contemporary, ultra-sleek garment that is so unstructured that it fits Gere more like a victory cape deftly grifted from a Gian Lorenzo Bernini statue. Underscoring its defiantly casual-cool factor is the fact that Armani’s coat has no button closures at all, and is only held in place by a single, sash-like belt. While Hollywood’s leading men have always had an intimate relationship with the world’s best tailors, this was, for the better part of the 20th century, a dialogue shrouded in secrecy. Few know that Steve McQueen sought out the sartorial arts of Douglas Hayward for The Thomas Crown Affair, or that Fred Astaire was a devotee of Anderson & Sheppard, or that Kilgour cutter Arthur Lyons (who also cut for the Duke of Windsor) made Cary Grant’s sublime grey suit in North by Northwest. But with Armani’s arrival onto the scene, for the first time, actors sought out a fashion designer to dress them both on the red carpet and, even more significantly, onscreen.

Armani did the costume design for several films — Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables and Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire, in particular, have created some of the most lasting images in contemporary cinema. For the former, which is set in Prohibition-era Chicago, Armani decided not to make replicas of clothing from that time, but, rather, to refract that period through his mind’s eye. He used his strong shoulders coupled with his signature soft bodies to dress Eliot Ness and his eponymous crew to great success. Who can forget Kevin Costner as Eliot Ness, in a suit and overcoat in varying monochromatic shades of intractable stoic blue and slate grey, racing down a long flight of stairs in slow motion — De Palma’s homage to the classic ‘Odessa Steps’ scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 Battleship Potemkin — his coat transformed into a billowing legionary’s cape. Though, here, it must be said that the irrefutable sartorial scene-stealer in The Untouchables is Robert De Niro as Al Capone. In this film, as with American Gigolo, it is a camel-hair coat that best embodies the persona of its wearer. Fittingly, in Capone’s case, his coat is fitted with a sinister black velvet collar and swells with ursine gravitas.

Time and again, Armani has collaborated with directors to create some of the silver screen’s most lasting imagery. The list of films which he designed costumes for include Hurlyburly, The Object of Beauty, The Grifters, Jerry Maguire, Entrapment, Gattaca and many more. Even more significantly, Armani has been unofficially co-opted onscreen by actors such as Mickey Rourke to create his character in the seminal 9½ Weeks, as well as by director Michael Mann for his cast in the seminal television series Miami Vice. Offscreen, there has been an innumerable litany of stars who have donned Armani, though Tom Cruise asserted himself particularly well in a high-gorge, wide, peaked lapel, double-breasted, four-button tuxedo at the 2009 Golden Globes — one of the most classically handsome garments ever to be walked down the red carpet.

Demonstrating his enduring relevance, almost a full 40 years after the debut of his very first men’s collection in Milan, Armani is still a major force in cinematic costume design, most recently dressing Christian Bale in Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy. The caped crusader, created by the DC Comics artist Bob Kane, has proven to be one of popular culture’s most enduring heroes, as well as its most complex. While heroes like Superman are largely one-dimensional, Batman was the first superhero widely believed to be affected by dissociative identity disorder: by night, a crime-decimating vigilante, clad in macabre costume and inspired equally by ancient samurai armour and the darkest recesses of the Freudian id; by day, the playboy-millionaire Bruce Wayne. But even in this latter guise, Bale’s Armani Made to Measure suit’s deconstructed principles constantly hint at his underlying musculature, and the alter ego that lies just beneath the grey pinstripes, pacing restlessly like a caged predator.

In 2001, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York enacted a retrospective on Armani’s “radical innovations in the realm of clothing design that have transformed the face of contemporary fashion”. Now, over a decade later, we’ve seen that Armani has never stopped innovating. As the world reverts to classical ideals, there is no single fashion designer who is more relevant or more creative.

oNZglEtDBmc