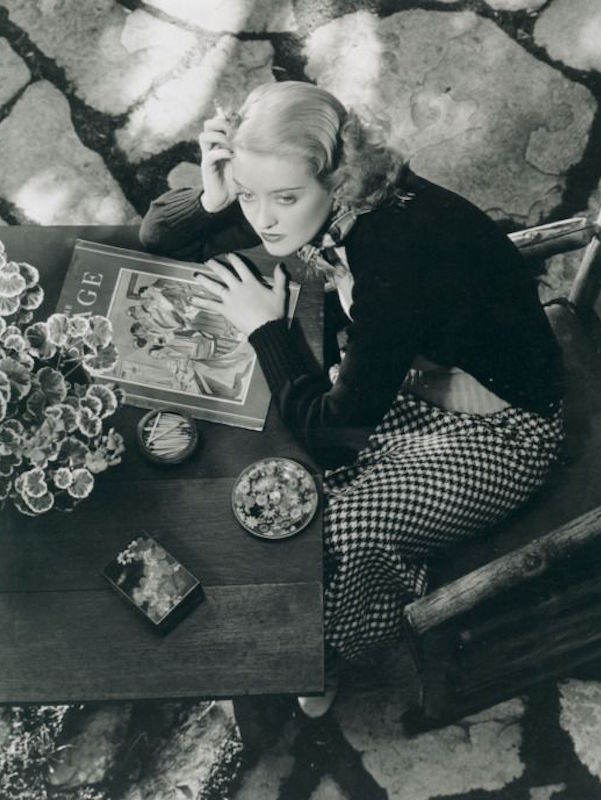

Bette Davis: Stars in Her Eyes

Willful, cutting, smart, ballsy, and all amid a cloud of cigarette smoke, Bette Davis was iconic for all the right reasons.

Bette Davis was an unlikely screen star. During her time in theatre - before cinema’s shift from silent to talkies brought a new demand for actors who also sounded good - she was dubbed the “little brown wren”, both for her unconventional looks and her retiring manner. But the person who grew out of that transformative shift was anything but meek. While she always fought shy of her status as a screen legend - “unless I’m performing I don’t think of the professional part of my life, so there’s no way you can think of yourself as a legend,” she argued - shy in coming forward with an opinion she certainly was not. “Fasten your seat belts - it’s going to be a bumpy night”, indeed.

It was an attitude that would suit her screen persona: willful, cutting, smart, ballsy, and all amid a cloud of often maliciously-directed cigarette smoke. But it was real too, even when she remained relatively unestablished. The actress who in time would receive ten Oscar nominations and two wins (Davis claimed to have named the golden statuette - after her husband, since they shared the same shapely behind) described herself - in a kind of anti-hagiography of the kind Hollywood stars are not used to - as “insufferably rude and ill-mannered.” She was, she said, “uncompromising, peppery, intractable, monomaniacal, tactless, volatile and ofttimes disagreeable.”

Standing her ground was hugely risky to a movie career - she would have been dropped by Universal were it not for a cinematographer noting to the studio heads that she had “lovely eyes”; such was the fragility of her position. Take her breakthrough movie, Of Human Bondage (1934), for example. This saw Davis take on a part that had been rejected by several actresses; ironically perhaps, given that it would be such better-written, more villainous parts that in time would win Davis such iconic standing. And yet, the same year, her future still uncertain, she was already bucking against Hollywood. Universal, the studio to which she was contracted, wanted to overhaul her image for the comedy Fashions of 1934, notably by remaking her in the look of Greta Garbo. Davis was having none of it.

“It was sickening because it wasn’t my type,” Davis recalled in interview in 1975. “And thank god I had brains enough to realise that. And I never let them do that again. I said either fire me or let me be what I am. I was a meddler for my own good. But really it becomes self-preservation. They did it with so many theatre people - changed their teeth, their nose, everything. And those with any individuality never made it because they looked phony.”

Such strong-headedness was perhaps all the more risky for Davis especially - a serious actress, unafraid to take on the less sympathetic parts her peers shunned, favouring a larger than life performance style and with little time for ‘the method’, work was eminently important to her. She even claimed that although you may have many disappointments in life, “the one thing that stands by a human being is their work." But her bullishness also won her great respect. “I was thought to be ‘stuck up’. I wasn’t,” she stressed. “I was just sure of myself. This is and always has been an unforgivable quality to the unsure.”

But her chutzpah was no doubt also a strain too -“when a man gives his opinion, he’s a man. When a woman gives her opinion, she’s a bitch,” she noted. In 1936 she complained about the film studios running what she called a “contract slave system", decided to break her contract, then with Warners, and go to England to make two movies. Jack Warner, one of the studio’s bosses, asked Davis not to leave, telling her that he’d just bought the film rights to a wonderful book - and that he wanted her to have the lead. “’I’ll bet it’s a pip!’,” she exclaimed haughtily, before walking out of his office. The role was Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind. Warner sued - preventing Davis from working. But when she returned to the US they offered her a new deal - fewer movies, for much more money. The films that followed through the 1940s - culminating in All About Eve - arguably made them her golden years.

As she put it: “Without things to overcome, you don’t become much of a person, do you? I know what I want as my epitaph. Here lies Ruth (her given name) Elizabeth Davis - she did it the hard way.”