The Bootleg Brethren: Prohibition's Heroes

How the lesser-known ne'er-do-wells of The Prohibition wove, with their antics, some of the richest folklore in American history.

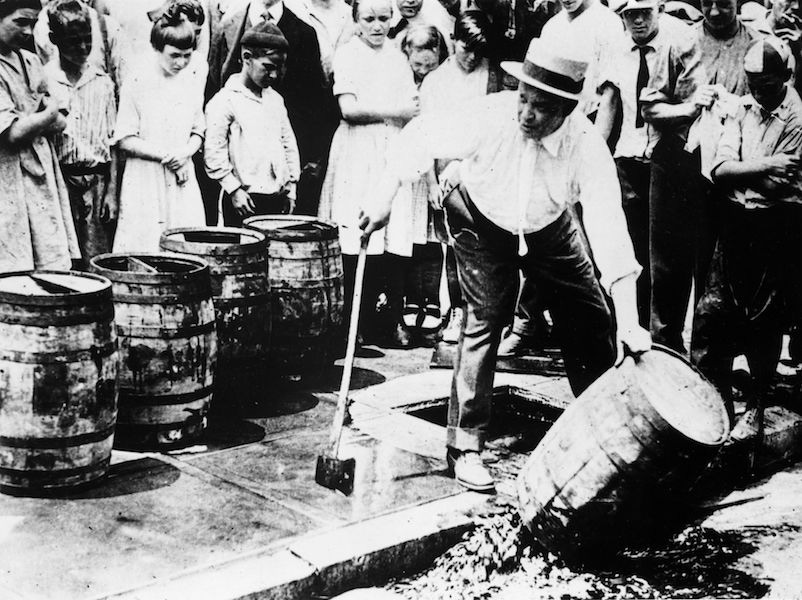

It was meant to be a moral crusade that would cleanse depraved cities, bolster public health and promote temperance amongst the “wretched refuse” from distant lands. It would, proponents believed, overwhelm the whiff of Sour Mash with the musty smell of the Protestant priggery. Instead, it dragged America into a state of prolonged lawlessness: “There’d never been a more advantageous time to be a criminal in America than during the 13 years of Prohibition,” as author Bill Bryson once commented. “At a stroke, the American government closed down the fifth largest industry in the United States - alcohol production - and just handed it to criminals.”

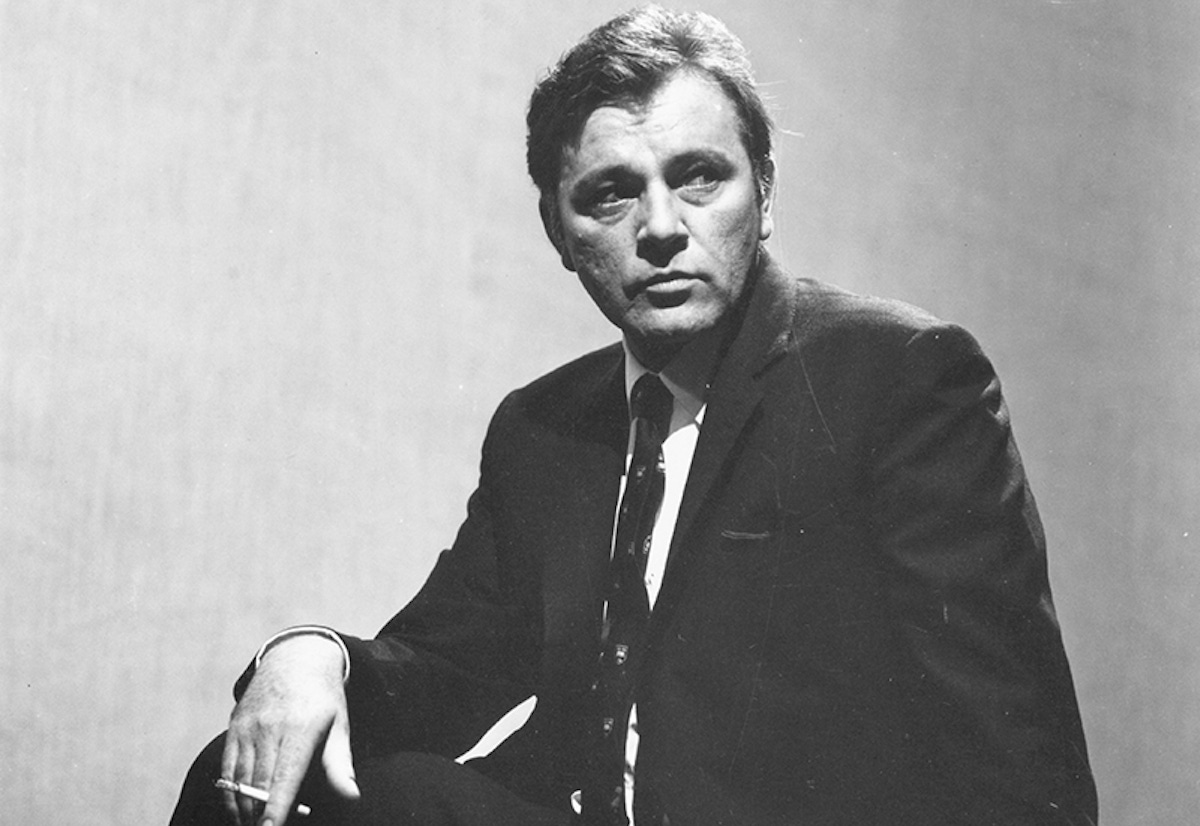

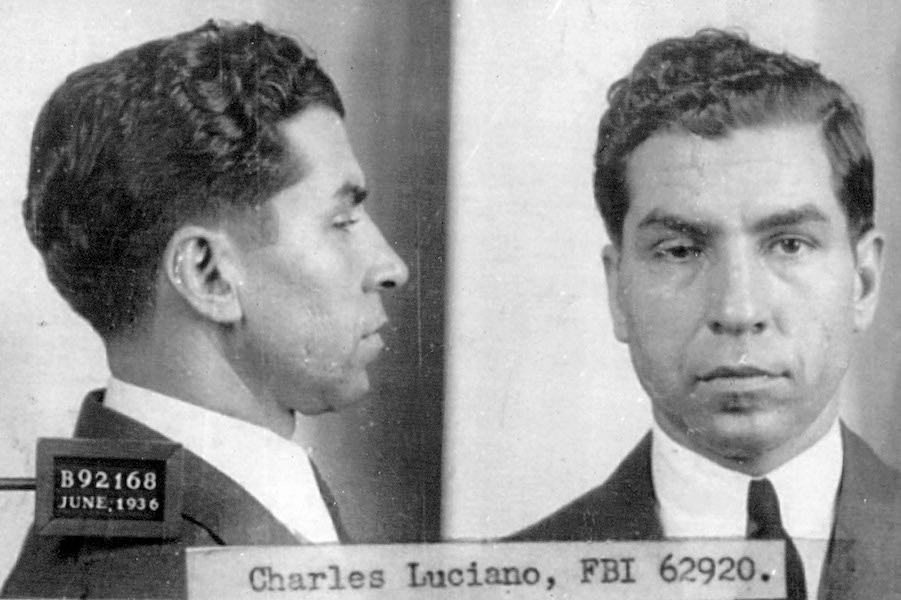

The passing of the Volstead Act was a remarkable act of folly, undoubtedly: but it also turned out to be one of pop-cultural alchemy. Criminal entrepreneurialism makes for a cracking story, hence the escapades of big-name gangsters of the time - Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, as immortalised in Boardwalk Empire – being ingrained in American folklore almost a century after the incidents which made these men infamous took place.

Gangsters tend to hog the limelight - but what of the other system-flaunting rascals? Many others’ escapades during this freakish window of American history are equally deserving of a wry, retrospective giggle. Al Capone – who ran an illicit drinking hole out of the Biltmore Hotel while staying in the 13th-floor Everglades suite, as well as owning the Garden Club in Chicago - certainly doesn’t have a monopoly when it comes to rakish antics by speakeasy proprietors. Take Lee Chumley, for example - “a laborer, soldier of fortune, stage-coach driver, ‘wagon tramp’, artist, waiter, newspaper cartoonist and editorial writer”, according to his New York Times obituary.

"The American government closed down the fifth largest industry in the United States - alcohol production - and just handed it to criminals.”Ernest Hemingway, Dylan Thomas, F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Steinbeck were among the literary giants who would sink illicit Gin Rickeys and Sidecars in Chumley’s Greenwich Village establishment, the walls of which were lined with framed dust jackets of their works, and whose owner – distinctive with his dapper floppy hat and necktie worn with an open shirt – was such a incandescent radical, he made his establishment HQ for the fiercely anarchist Industrial Workers of the World labour union. If Chumley was one of the Prohibition’s more radical protagonists, its most cunning were surely cousins Jack Kriendler and Charlie Berns - Austrian-Yiddish immigrants from New York’s Lower East Side who opened their first watering hole in 1922 in Greenwich Village to pay for night school. No one circumvented the Prohibition’s laws with as much guile as this pair: they changed their establishment’s name constantly to befuddle authorities; they installed a button that flicked the shelves over so that the liquor would all fall into a shaft at a second’s notice; they disguised a 4,000-pound door leading to a wine cellar as a brick wall. Kriendler and Berns were only arrested once, and in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pardoned Berns for his conviction. Make of that what you will. One man who didn’t escape the wrath of the law was Tony Marino, owner of the speakeasy at 3804 Third Avenue at which he and four other miscreants hatched a plan in 1932: to insure the life of barfly Mike Malloy, a dipsomaniac from Donegal, then hike up his bar tab allowance, watch him slowly imbibe himself to death and share the pay-out. Malloy turned out to be made of sturdier stuff than the consortium had anticipated: Marino added wood alcohol, antifreeze, rat poison and turpentine and even pure poison to his drinks, and still the Irishman kept coming back for more.

So Marino gave him a sardine sandwich with ground tin sprinkled between the bread slices: Malloy quaffed it down and asked for another. One below-freezing January night, they doused him in cold water and left him in the middle of Claremont Park - Malloy swaggered into the bar the next morning needing something medicinal to combat a minor sniffle. Even the impact of a speeding taxi didn’t do for him. Eventually, carbon monoxide administered via a gas jet proved that Malloy was, after all, mortal. Marino and his accomplices were slain - at the first attempt - by the electric chair shortly afterwards.

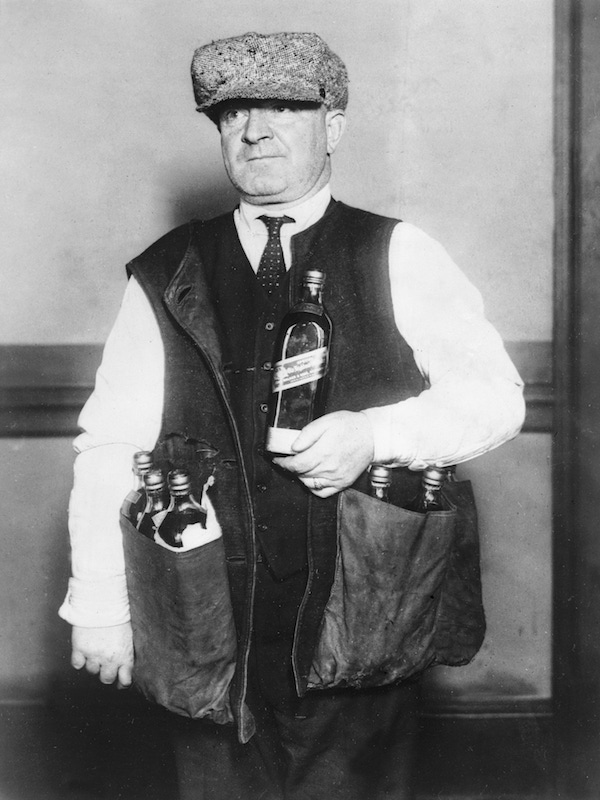

Of course, there would be no speakeasies, and therefore no colourful idiosyncratics to run them, without bootleggers to provide them with a commodity: men such as Bill McCoy - a builder of luxurious speedboats until a one-off shipment of rum from the Bahamas to Georgia in 1921 saw him trouser $15,000, and quickly realise the lucrative potential of trafficking bona fide Caribbean rum as opposed to the homemade swill and moonshine generally bleaching palates in the US at the time (hence the still popular phrase ‘The Real McCoy’). McCoy made $300,000 in profit each time he made the journey to the Bahamas from Martha's Vineyard and back on his vessel the Arethusa. A kind of early 20th Century Walter White, he never indulged in his own product himself, and took pride in the fact that he never paid a cent to organized crime, politicians, or law enforcement for protection.

"McCoy quickly realised the lucrative potential of trafficking bona fide Caribbean rum as opposed to the homemade swill and moonshine."The man behind a vast amount of grog supply to the Pacific Northwest region, meanwhile, was one Roy Olmstead, who began to bootleg part-time while still a young, promising lieutenant on the Seattle police force. Sacked for his misdemeanours soon after federal agents raided a tugboat full of Canadian whiskey on a beach in Edmonds, Washington State, he was soon making more in a week as Seattle’s “Rum King” then he would have done on the right side of the law. Rumours abound that Olmstead’s wife Elsie wove coded messages to rumrunners on Puget Sound into children’s stories which she broadcast each night from a makeshift radio station installed in their mansion. Perhaps the king of all the Prohibition’s picaresque characters, though, is Charlie Birger – a man whose extraordinary life neatly demonstrates the amorphous nature of human morality. Born Shachna Itzik Birger to a Jewish family in Russia around 1880, Birger, having been brought to the US aged eight, enlisted with the 13th Cavalry Regiment in South Dakota before deciding to make a hefty living supplying southern Illinois with whiskey and beer. Charismatic, insouciant and whimsical, Birger would frequently take to the street with a cigar box full of coins and throw handfuls in the air for neighbourhood children to scoop up. During the various violent scrapes into which his profession landed him, he slayed several members of the passionately pro-Prohibition Ku Klux Klan, an act which few today would proscribe. “It's a beautiful world” were his final words on the gallows. Despite the lawlessness and homicidal tendencies, it’s tempting to suggest that Birger and his ilk helped to make it so.