Bruce McLaren: Motorsport's Overachiever

The life, death and extraordinary legacy of Bruce McLaren, founder of the eponymous marque and all-round motorsport icon.

The glorification of untimely death is nothing new. “It is a lovely thing to live with courage and to die leaving behind an everlasting renown,” was supposedly Alexander The Great’s take on the matter, before he carked it age 32. A couple of centuries before Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix vomited their mortal coils into the abyss in return for a “27 Club” membership card, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron died at the ages of 25, 29 and 36, respectively.

In motorsport mythology, though, premature demise provokes an altogether different level of reverence. There can only be one reason for this. Practitioners of motorsport – in a bygone age, at least – put their lives on the proverbial green baize when carrying out their actual raison d'être. Fifty-one drivers have died on the F1 track alone, from Britain’s Cameron Earl in 1952 to France’s Jules Bianchi three years ago, via, most famously, Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna’s deaths on the same weekend in 1994. So it was both poignant and apposite when motorsport writer Eoin Young remarked that New Zealand motorsport legend Bruce McLaren “virtually penned his own epitaph” with a passage in his 1964 book From the Cockpit, dedicated to the death of his teammate Timmy Mayer:

“Who is to say that he had not seen more, done more and learned more in his few years than many people do in a lifetime?” McLaren wrote. “To do something well is so worthwhile that to die trying to do it better cannot be foolhardy. It would be a waste of life to do nothing with one's ability - for I feel that life is measured in achievement, not in years alone.” Six years after its publication, aged 32, McLaren was killed while testing a Can-Am McLaren at Goodwood Circuit (on the Lavant Straight, just before Woodcote Corner, his vehicle was destabilised when rear bodywork flew off and McLaren hit a marshal’s post).

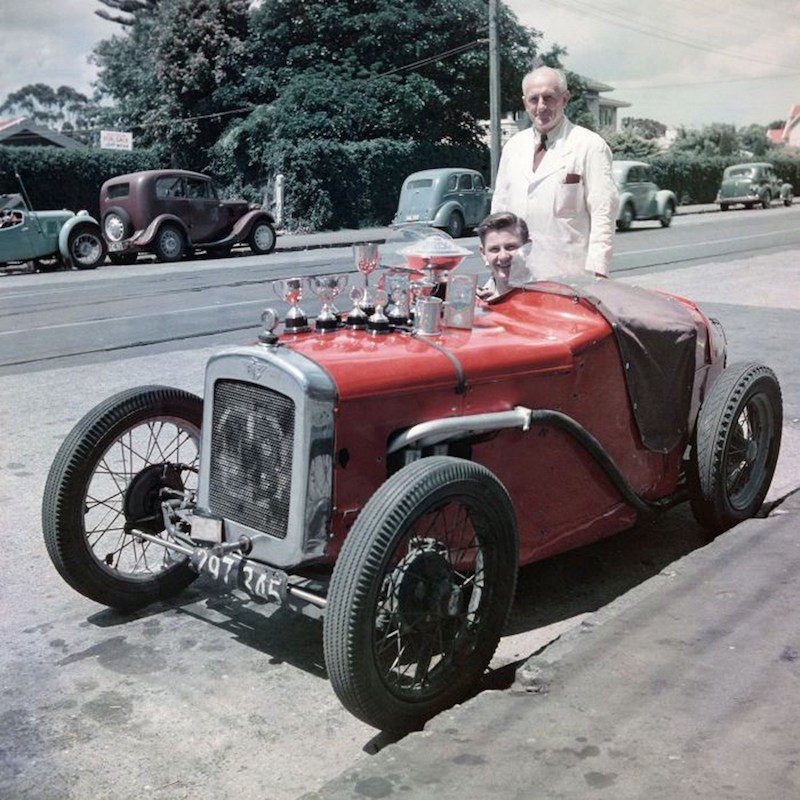

McLaren is a member of a club far more illustrious than the one populated by rock stars who stepped into the abyss three years shy of their thirties thanks to ingestion of booze and mind-benders. Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson, Vincent van Gogh and Franz Kafka are all among his peers when it comes to achieving Alexander The Great’s ‘everlasting renown’ posthumously - and McLaren did it in the face of more adversity than most. Born in Auckland in 1937, having contracted Perthes Disease, a hip joint problem, he spent two precious childhood years on a rectangular metal orthopaedic device called a Bradford Frame in the family home in Takapuna. His fascination with all things automotive began with his father bringing a decrepit 1929 Austin 7 back home one day, which became a plaything for both father and son. The 13-year-old McLaren Junior cut his driving teeth by thrashing the vehicle around the lemon trees in the back yard.

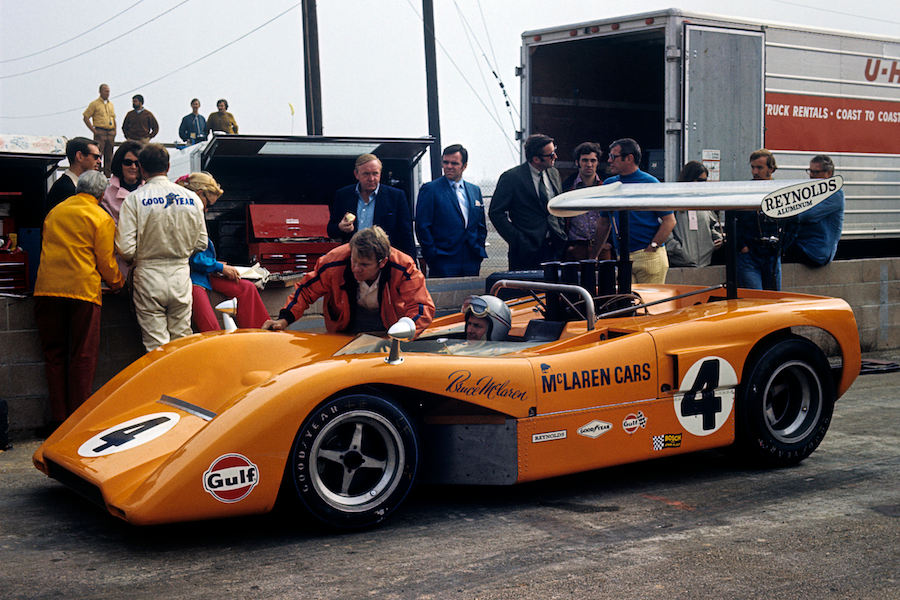

The driving career that followed was modest – at least in terms of trophy hauls. McLaren won only four Grand Prix over a 12-year Formula 1 career (although he was just 22 years and 104 days old when he won the 1959 United States Grand Prix, making him then the youngest ever GP winner), and he also clocked up a victory at Le Mans in 1966 and two Can-Am championship titles in 1967 and 1969.

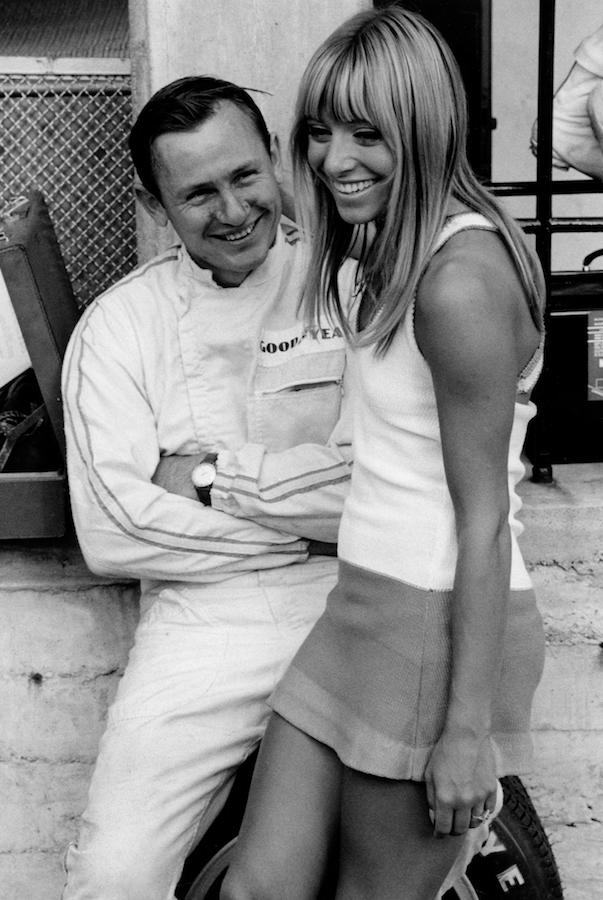

But it was his capacity as a racing car constructor that makes Bruce McLaren a household name to this day. His engineering nous is the stuff of ardent oily-rag sniffers – the introduction into car design of ‘nostrils’ that enhance airflow and stop flapping filler caps, and the like – but his sheer charm, charisma and grace had universal and timeless appeal. On the day of his death, Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd consisted of a handful of employees, who assembled to hear the news in a humble workshop in Colnbrook, Berkshire: that day, they lost not just their founder but their driver, designer, engineer, chief mechanic, mentor and friend (he was godfather to a number of his employee’s children).

One of the McLaren team’s co-founders Tyler Alexander, having heard the news in Indianapolis the day after the Indy 500, flew back to England immediately in order to galvanise the team. “It’s times like these when you have to get a hold of yourself and keep people together - in this case, the people who helped to make Bruce McLaren Motor Racing the team that it was,” he wrote in his book, A Life & Times With McLaren. “It was now time to use the things that we all had learned from Bruce, without showing personal sorrow.”

A little shy of half a century on, McLaren’s F1 team has won 20 World Championships (12 for drivers, eight for constructors), 182 Grand Prix, and also triumphed in the Le Mans 24 Hours and the Indianapolis 500. “Everlasting renown”, it’s fair to say, barely scratches the surface.

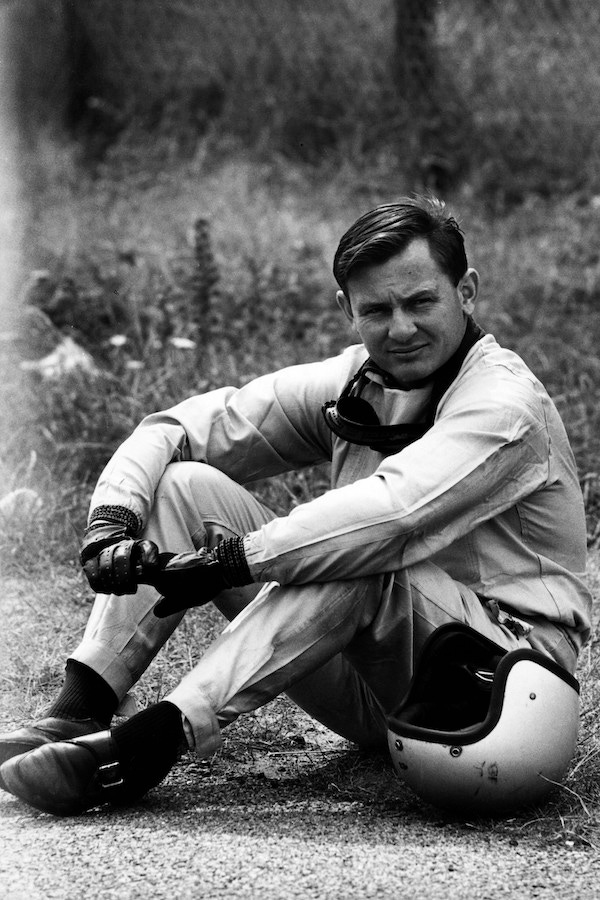

McLaren enjoying a few laps during testing at Goodwood in 1964. He would suffer a fatal crash at the same circuit six years later.

McLaren enjoying a few laps during testing at Goodwood in 1964. He would suffer a fatal crash at the same circuit six years later.