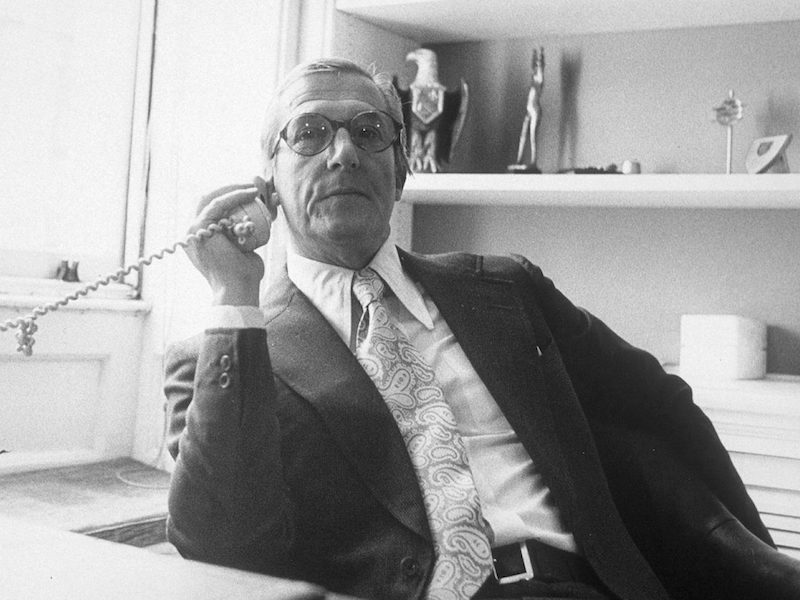

By Royal Appointment: Sir Hardy Amies

Arguably one of the most influential designers of the 21st century, Sir Hardy Amies' refined tastes extended far beyond the end of the catwalk.

“I have absolutely no desire to do anything too revolutionary with men’s fashion,” as the tailor and couturier, gent and roue, Hardy Amies once explained, before going on to do just the opposite. “I think men have just got used to the idea of where the pockets are.” But then again, in the 60s Amies’ idea of future style foretold of us wearing slim bow-ties, high-buttoning cutaway jackets and extra narrow trousers - all excellent predictions, were it not for the fact that he also suggested said trousers would be worn tucked into calf-length boots.

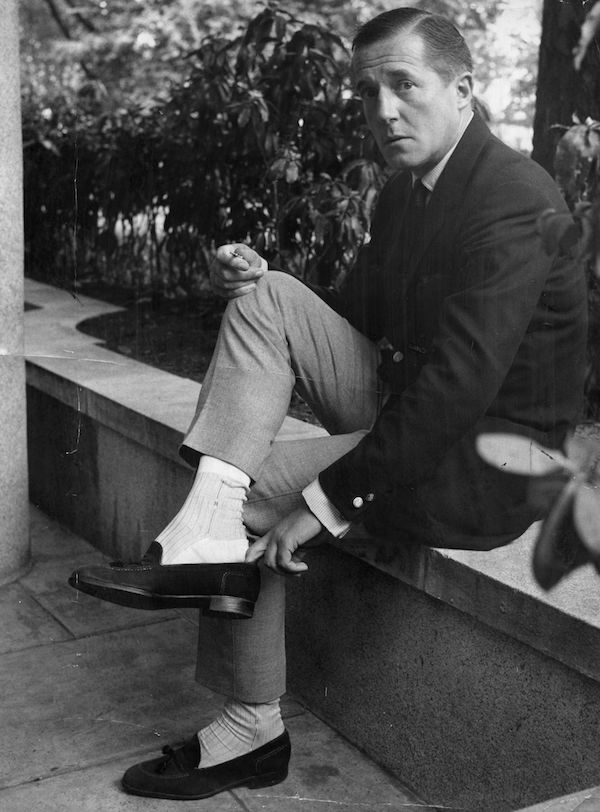

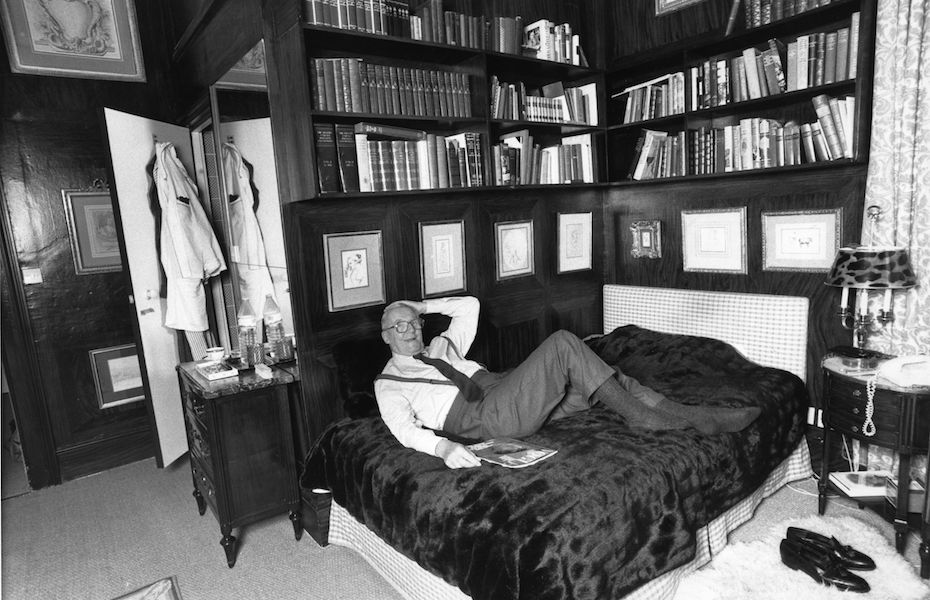

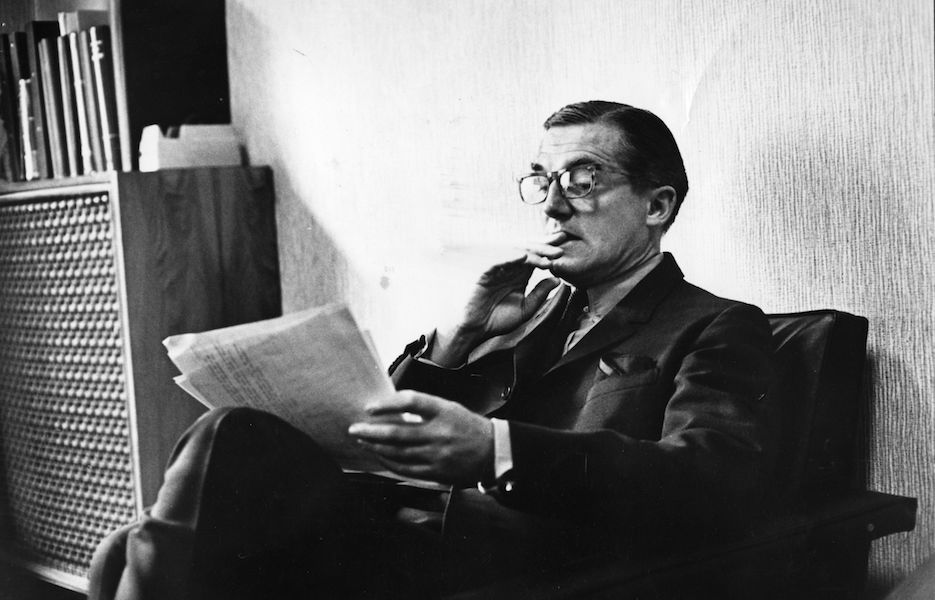

So the flamboyantly outspoken Amies - who died aged 94 in 2003, leaving the legacy of his design approach and company behind him - did not always get it right. But few could question the progressiveness of his vision, as a designer, businessman and, surely, a man after The Rake's heart. Amies - always tailored - would have considered much of today's wardrobe to be what he used to call "leisure clothes".

He, after all, once defined casualwear by the stark contrast to that which he considered proper - “clothes you wear when you aren’t wearing a suit".

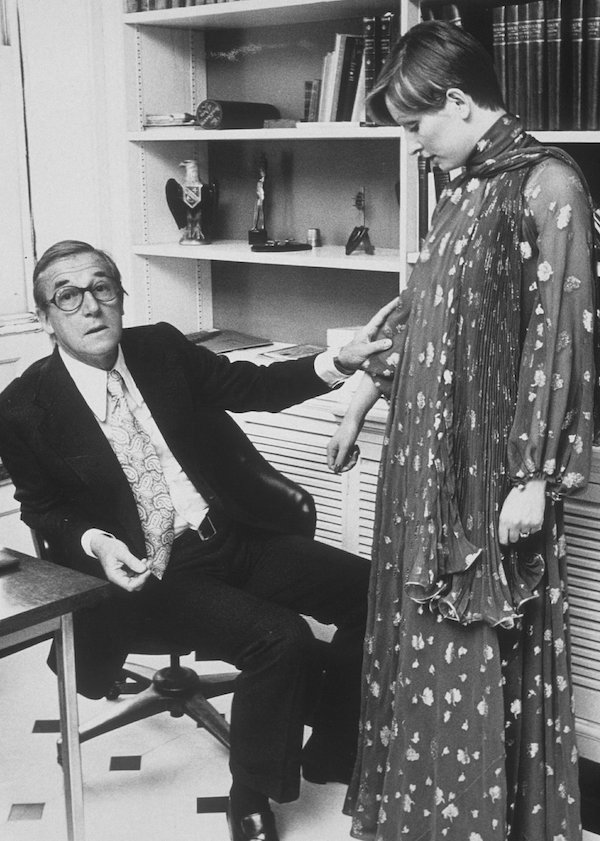

So attitudes to dress have changed too. But our very conception of menswear - its status today, its place in society - owes a debt to him. Often misunderstood as, primarily, a womenswear designer - remarkably, he was dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth from her accession to the throne to his retirement in 1989, and he did collect needlework, after all - Amies was far more dynamic in his approach to menswear.

This year, for instance, marks the 50th anniversary of his ground-breaking costume designs for Kubrick's ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ - not just the Pan Am space cruiser's stewardesses, with those clever grip shoes, or the signature boldly-coloured space suits, but those Prada-esque, high-buttoning, narrow lapelled, crop legged tweed suits worn by the likes of Leonard Rositer, recognisably not of the 1960s but not so futuristic as to date the film half a century either. Amies would go on to dress Patrick McNee in The Avengers TV series as well.

Amies was innovative in more than design too, but in business and brand-building. He dressed the 1966 World Cup England team, a first in sport for a fashion designer of his standing. He was the first fashion designer to expand into homewares. He was the first designer to host a menswear catwalk show, at the end of which, with tongue firmly in cheek, a huge papier mache hand once appeared out of the wings. That, Amies would later explain to a perplexed audience, was the Queen waving. Amies would also take a bow at the conclusion to his catwalk presentation. Now the done thing for designers, he was the first to do this as well.

Given menswear's reputation then as the purview of the decidedly unmasculine, Amies - a self-described "clever old queen", while his rival Norman Hartnell was, he said, merely a "silly old queen" - bucked that stereotype too, at least if you dug into the personal history of which he rarely spoke, a stance that was common to a generation that had seen horrors.

Clearly a talented designer from the off - without formal training, Amies saw a photo of a Lachasse dress, wrote to the company commenting on the draping effect, was offered a job and was managing designer within a year - the interruption of World War Two saw him joining the Belgian section of the Special Operations Executive.

For this he trained agents, ran assassinations and all, naturally, using the names of fashion accessories as code words. He saw brutal close action himself too, garrotting at least two men. His efforts saw him knighted by the Belgians in 1946, long before he was recognised by his mother country. When he launched his eponymous business after the war his main backer was Virginia Cherrill, an American actress and the first wife of that other man of style, Cary Grant.

One military report summed Amies up to a tee: "This officer is far tougher, both physically and mentally, that his rather precious appearance would suggest". Likewise his bon mots on correct dress - his ABC of Men's Fashion remains seminal and, of course, made him one of the first designers to put his pronouncements print - suggest a man far more frivolous than he actually was.

Indeed, Amies was a master of role play and reinvention from the off - born Edwin Amies, he took his mother’s maiden name as his first. It sounded better, he mused. And he was good with musings, off-hand, haughty, often hilarious, perhaps only rarely meant. "A man should look as if he's bought his clothes with intelligence, put them on with care and then forgotten all about them," may be his most famous, but it is far from being his most memorable, or his most funny. Underwear, he noted, "should be as brief as wit and as clean a fun". But, best of all: "Remember," he noted, "every time you sit down you are ironing a suit in the wrong places". His kind is missed.