Certified Original: Peggy Guggenheim

Collector, bohemian, socialite. The list of Peggy Guggenheim's accomplishments goes on and on, as does her enduring legacy to the world of fine art.

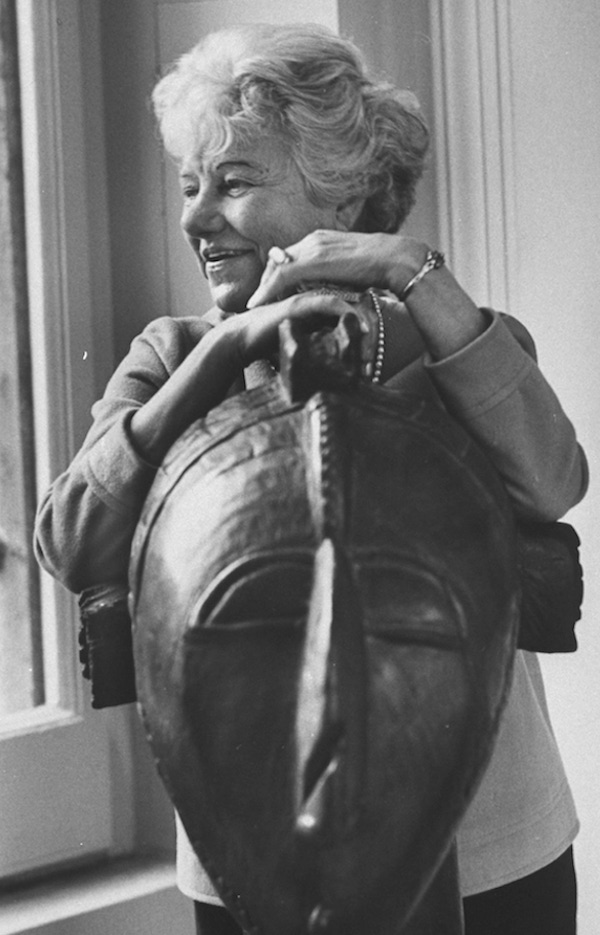

Peggy Guggenheim is said to have had a thousand lovers, but she only truly had one: art. Through a combination of privilege, ego, opportunism and drive, she didn’t buy art because she knew it’s intrinsic or predicted value, because when she built much of her collection there was simply no market to speak of. Instead, she bought because the art spoke to her, because she saw something in it that captured her intellect and imagination, that she knew was inherently worthy. In this way, perhaps no other mind of the 20th century has had such a singular impact on the definition of what constitutes modern art. She represented a new kind of serious collector - one who did not have roots in aristocracy or royalty; one who instead was relentlessly forward-thinking.

She was born into money of course. The daughter of Benjamin Guggenheim (metals) and Florette Seligman (banking), her childhood was one of privilege, though it was far from happy. She felt she could never fit in - something not helped by her neglectful mother, who left her in the care of strict and vindictive nannies. Her father died in the sinking of the Titanic, and thus she inherited the not-inconsiderable sum of $450,000.00 - about $5 million today. In her early twenties, desperate to escape her upper-class social circle, she took a job at an avant-garde bookstore. She didn’t need the money, but it put her in the path of more creative thinkers, notably Alfred Steiglitz, future husband of Georgia O’Keeffe. It was at his gallery, being exhibited in America for the first time, that she encountered the works of Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso. She was hooked straight away.

Peggy relocated to Paris in the early 1920’s; it would become her home base of sorts for the next twenty two odd years. Collection was her primary motivator, both of art and of lovers. Independent, confident and curious, she was a great seducer and experimenter, and dabbled with almost every artist that crossed her path, and many more. Once asked how many husbands she’d had, she famously replied “Do you mean mine, or other people's?" She had two, disastrous marriages, first to failed author Lawrence Vail, with whom she had two children and who would rub jam in her hair when they fought, and then to painter and sculptor Max Ernst. Ernst was less deliberately brutal, though the marriage was still regarded as something of a catastrophe in retrospect. Thankfully both marriages ended relatively swiftly.

The great surrealist Marcel Duchamp had become a firm friend of Peggy’s during her time in Paris. He would often accompany her when she went buying, and she was a quick study, eager as she was with many of the artists she worked with - to understand his personal aesthetic eye. “I took advice from none but the best”, she said. “I listened, how I listened! That's how I finally became my own expert.” In 1938 she applied that expertise to opening her own gallery, Guggenheim Jeune, in London. Open for just over a year, it was one of the first modernist galleries, and hosted work by such luminaries as Duchamp, Henry Moore, Jean Cocteau, George Braque, Constantin Brancusi and Pablo Picasso. None of these artists were famous, far from it. But she knew.

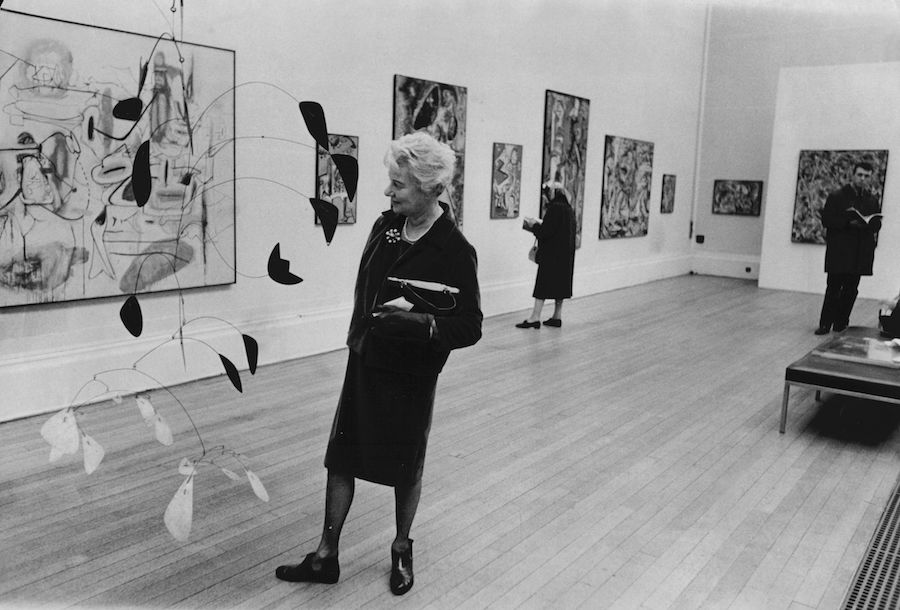

The looming spectre of war over Paris did not escape Peggy’s notice; with the Nazis inching closer to France, she committed herself to buying a picture a day, amassing much of what would become her collection for a mere. When conflict finally did break out, the Louvre refused to store it, claiming that none of the pieces were worth saving. After fleeing Paris, she opened the gallery she’s most famous for, New York (and later London’s) Art of This Century. Part gallery and part standing museum, it helped certify New York as a centre for modern art. It was also the vector through which she met what she regarded as her greatest discovery: Jackson Pollock.

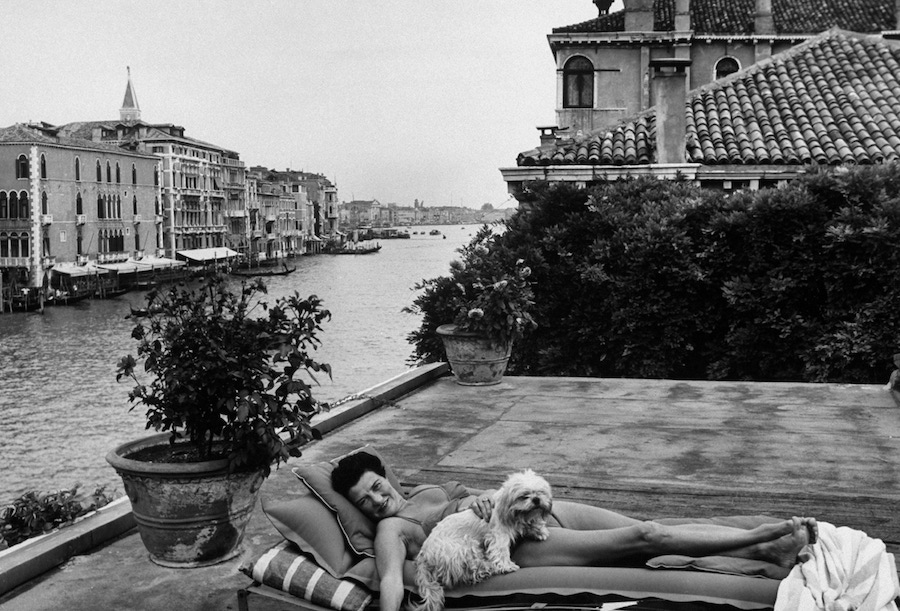

When World War II wound to a close, Peggy decided to relocate once more, to Venice. She purchased the beautiful (and forever half-finished) Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the bank of the Grand Canal in 1948, storing her collection there and using it to host huge parties (though she was notoriously cheap with the catering) and entertain lovers. Despite one Italian princess remarking that her place would be beautiful, if only she’d throw all that ugly art in the canal, Peggy’s presence made Venice a thriving modern art hub as well - something that continues to this day through the Venice Biennale.

It also continues through what had been Peggy’s raison d'etre for relocating to Venice - to build a museum. Sharing her passion for art had always been part of her nature, and her way of following in her family’s philanthropic footsteps was to open her palazzo up to the public in the early fifties. Towards the end of her life she donated her collection to her Solomon’s foundation (of New York’s Guggenheim Museum) - on the condition it stay in her house in Venice, where she would also be buried. “It’s horrible to get old,” she said not long before she died. “It’s one of the worst things that can happen to you. But I really felt I accomplished what I wanted to do, and I’ve done it very successfully, and I’m very happy about that.”

Hard to argue with that, Peggy.