The Director's Cut: Sam Peckinpah

The Rake continues its celebration of rakish artistry, with a toast to the life and work of the troubled auteur and unofficial king of the posthumous director’s cut.

“It was merely a changeover from dishonesty to at least looking at the fact that people do bleed and are hurt,” Sam Peckinpah told Barry Norman in 1976, when the British film critic quizzed him about a reputation for on-screen violence which had furnished Peckinpah with the epithet ’Bloody Sam’. “I made The Wild Bunch because I still believed in the Greek theory of catharsis – that by seeing this we will be purged… and get this out of our system. I was wrong.”

It’s not certain what overturned Peckinpah’s view that violence gilds realism with probity, but the catalyst may well have been the nausea he felt upon learning that his 1969 epic western The Wild Bunch was being shown to Nigerian soldiers to inspire them before battles. Either way, his reputation is reductive - many are surprised to learn that Peckinpah’s reputation as a man not disposed to letting a bucket of theatrical blood go to waste only really stems from a handful of pictures from his 14-movie oeuvre: notably The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia – the last of which, admittedly, sees a lone protagonist driving around Mexico with a severed head in a sack. It’s a shame, as his reputation for blood and guts is one that clouds the beauty of his artistry.

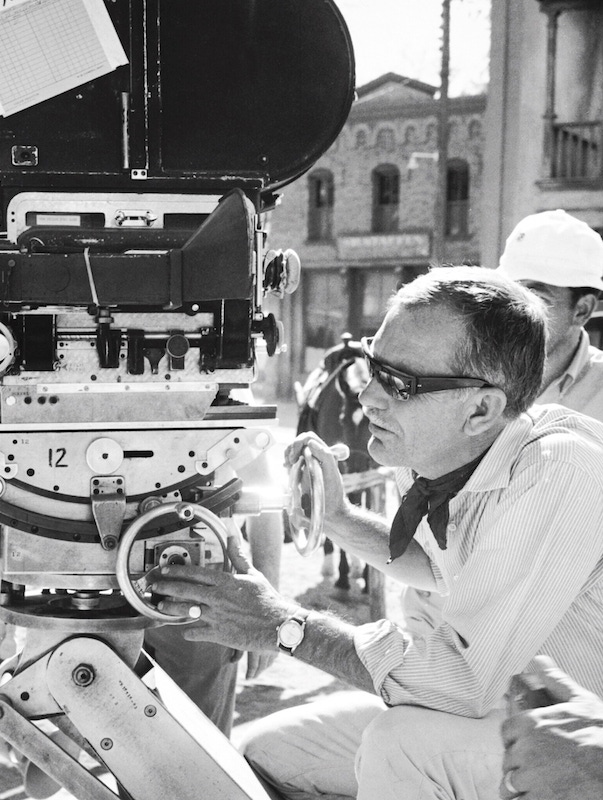

"It’s a shame, as his reputation for blood and guts is one that clouds the beauty of his artistry."Peckinpah’s filmic texts are magisterial in their crafting and guile. The hyper-frenetic action scenes which became one of his many trademarks sometimes involved running several cameras at various frame-rates, then stitching the results together in cuts often less than a quarter of a second in length. (John Woo – one among a list of Hollywood notables who acknowledge Peckinpah’s influence that also includes Kathryn Bigelow, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino.) His dissections of the male psyche and brotherly bonds were gritty, adroit and apposite (although his depiction of women furrows the eyebrows more, the further we stride away from the gender politics of the 70s). Meanwhile, by dint of being gentler and more nuanced, many of his better works are the lesser-known of his canon: Junior Bonner, which came between Straw Dogs and The Getaway, is a warm and poetic eulogy to western life eliciting a measured performance from Steve McQueen, while Noon Wine – Peckinpah’s mesmerizing, 50-minute forgotten masterpiece – has a dark and delirious poignancy to it.

This is a man who would over-research and over-shoot then over-whittle, such was his vociferous attitude to his work, and who refused to stop working despite abject health inflicted by alcoholism and cocaine abuse (he once admitted he could no longer direct while sober) had reduced his health to tatters.

It was artistic integrity – buoyed by a firecracker temperament - that made him tussle endlessly with studio honchos. “A little judicious censorship is like a little syphilis,” he once said of producers’ and financiers’ tendency to tinker with his work (the Wild Bunch was subjected to more than 3,500 cuts, the most of any colour film in history), and one theory even has it that Peckinpah vilified and scrapped with the studio purse-string holders in order to generate friction and tension with which to infuse his work.

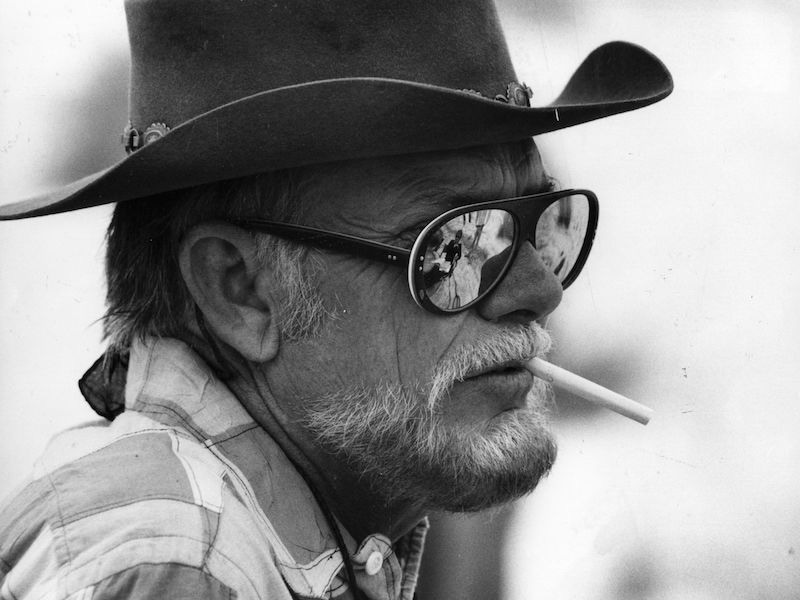

Perhaps it’s more simple than that, though, and the on-screen gore, grit and body-counts, as well as the turbulent relationships off it – Peckinpah was married five times, to three different women - were merely a result of old fashioned existential turmoil: inner torment which stemmed at least in part from chronic feelings of alienation. “I think of Sam as a man out of his time,” as Dustin Hoffman, who Peckinpah directed in Straw Dogs, once put it. “It’s ironic that he’s alive now, a gunfighter in an age when we’re flying to the moon.”

""A little judicious censorship is like a little syphilis,” he once said of producers’ and financiers’ tendency to tinker with his work."Peckinpah wouldn’t have argued. The son of a highly successful lawyer and judge, his ancestors – originally from the Frisian Islands off Denmark - had crossed the continent from Illinois in a covered wagon in the 1850s then made a fortune from logging and lumber. Peckinpah’s was a childhood spent riding hunting and fishing in the foothills of a mountain named after his family in Madera County, California, while summers were spent taking in the rough stoicism of ranch-hands and cowboys by osmosis. This world that characterised Peckinpah’s formative years – as depicted so evocatively in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – was declining into anachronism by the time Peckinpah took the baton from the man who directed it, John Ford. Any feelings of angst at one’s milieu disappearing over the horizon would have been deepened when his mother sold the ranch Peckinpah and his siblings had expected to inherit – something which may, observers have pointed out, contributed towards what many perceive as rampant misogyny in his work. The rampant substance abuse surely served as paraffin to the fire in his belly: it was during a stint in the marines in post-war China that he cemented a penchant for boozing (as well as whoring), and an attempt later in life to replace the latter with cocaine soon saw him addicted to both. Whatever stoked his fabled temperament, though, it had an alchemic effect on his work, and Peckinpah’s reputation as “The Hemingway of Hollywood” is as apposite today as it was when he died of heart failure in 1984, aged just 59.