The Director's Cut: Vittorio De Sica

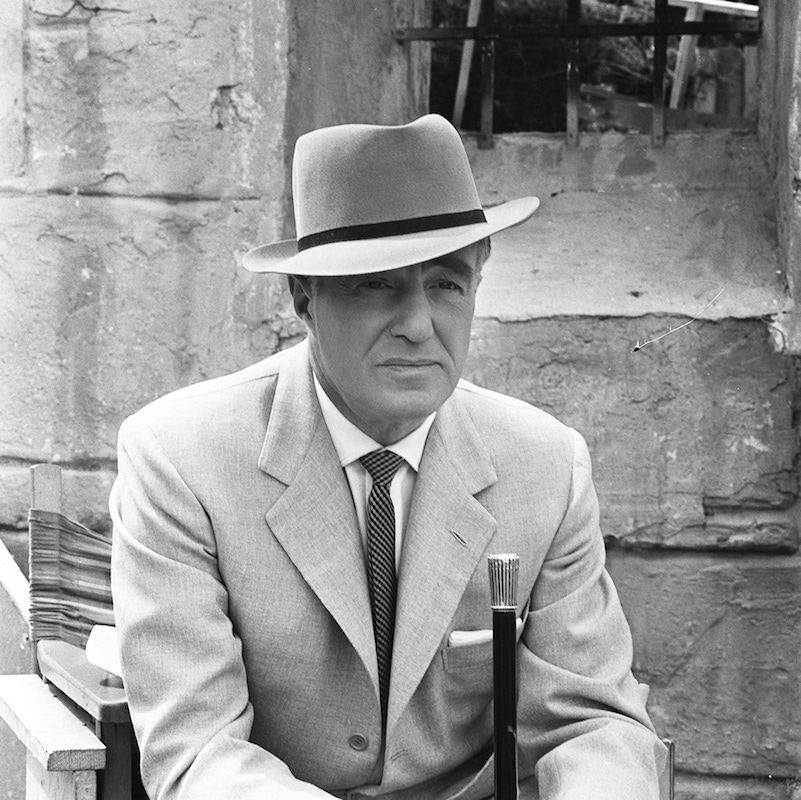

The Oscar winning Italian director may have been known for his double life and fiery dual personality, but that didn't stop De Sica from being heralded as one of the great story-tellers of the age.

The Italian Vittorio De Sica was a cinematic split personality, a debonair player of froth on-camera, an incomparable chronicler of political injustice behind it. As Michael Newton’s excellent Guardian piece on him put it, “it’s as if Hugh Grant were to suddenly metamorphose into Ken Loach.” Having grown up in a poor Neapolitan family, he started as a theatre actor, moved into film and found his richest seam with the screenwriter Cesare Zavattini. Four of the films they made together won Oscars and, by the end of his career, the esteemed novelist Cesare Pavese suggested that De Sica was the greatest Italian storyteller of their time.

Three post-war gems – Shoeshine, Umberto D. and The Bicycle Thieves, the latter regularly held up as one of the greatest films of all time - are universally gut-wrenching, deceptively artful fables (Umberto D. was said to be Ingmar Bergman’s favourite film). But they are also quintessentially Italian responses to the country’s own brand of fascism (compare the directness of Italian “neorealism” and the hanging of Mussolini from a Milan service station to Spain’s more oblique, Spirit Of The Beehive approach to its own dictatorship and the semi-deification of Franco in the monumental Valle de los Caídos). De Sica’s late masterpiece The Garden Of The Finzi-Continis (1970) became as elegiac a swansong as Visconti’sThe Leopard, the garden itself a complicated metaphor overgrown with innocence and nostalgia.

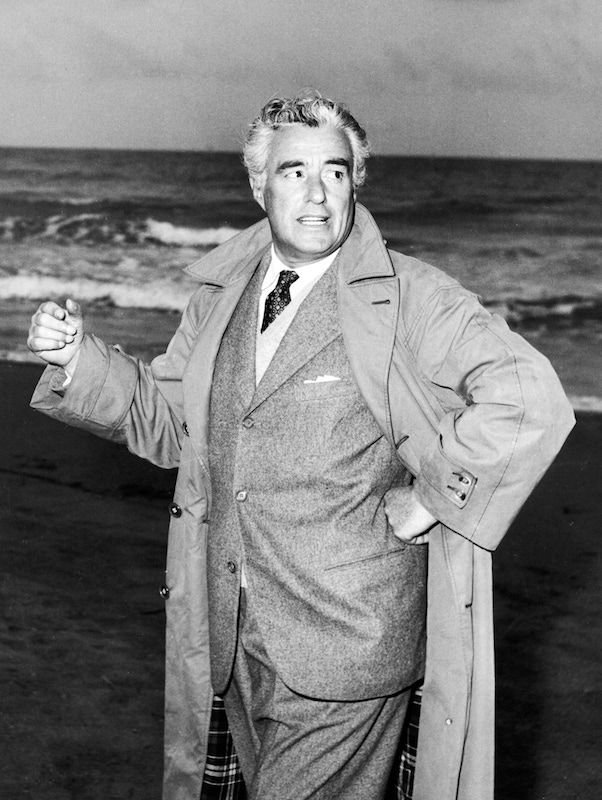

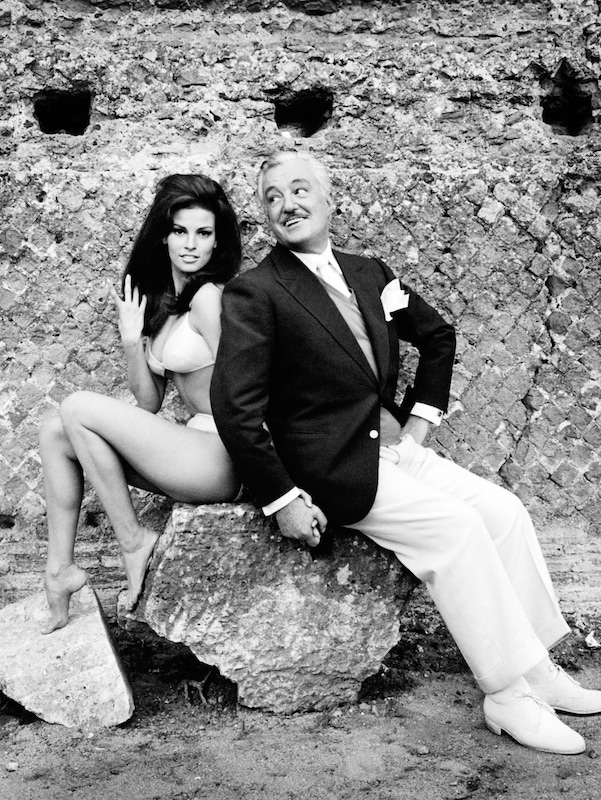

De Sica himself was an unusually handsome man and an accomplished international actor, nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for the 1957 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and star of the British action series The Four Just Men. Like a proto-Clooney, his charisma and understanding of actors enriched his ability to direct: on Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow, he showed no less than Marcello Mastroianni how to perform a sex scene with Sophia Loren by jumping into the bed and ravishing her.

"He showed Marcello Mastroianni how to perform a sex scene with Sophia Loren by jumping into the bed and ravishing her."Another De Sican duality was his acceptance of roles in mediocre films to finance the weightier films he wanted to direct; his love of gambling also meant he’d accept material beneath him to pay off his debts. The most curious is After The Fox with Peter Sellers, a hypnotically bizarre sixties sub-Pink Panther crime caper with wayward Italian accents, pratfalls, plonky theme tune and Britt Ekland – neorealism this is not. His fondness for a flutter was even channelled into his films: as critic Peter Bondanella notes in his book on Rossellini, the personality of Vittorio De Sica (inveterate gambler and likeable lady’s man) matched the role embodied in Rossellini’s General Della Rovere, just as the protagonist of De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves was chosen for the part because his experience and appearance suggested the kind of worker he was to play in the film. Perhaps the most personal duality was his Mitterand-style double family life. In 1937, De Sica married Italian actress Giuditta Rissone, who gave birth to their daughter Emi. Five years later, he met and started dating the Spanish actress Maria Mercader (whose brother Ramon, fun fact, had assassinated Trotsky!) After divorcing Rissone, De Sica married Mercader in 1959 in Mexico, but this union was considered void under Italian law, so in 1968 he took French citizenship and married Mercader in Paris, by which point he’d already had two sons with her. But even after his divorce, De Sica never fully left his first family: Giuditta liked the idea of their daughter still having a father figure, and De Sica would even put the clocks back at Christmas and New Year’s Eve to be able to toast both families the same night. Like Spencer Tracy’s relationship with Katharine Hepburn, this oddly progressive open-secrecy was contorted by a lifelong Catholicism, and religion saved De Sica’s life at least once. In the 1930s, he was asked by Goebbels to head the fascist cinema in Prague. Fortunately he was able to turn it down as the Vatican had just asked him to direct the religious film The Gates of Heaven. On the day he finished it, the American army arrived in Rome. A double-godsend. Italy has a rich tradition of rakish directors, some of whom (Fellini, Antonioni, Pasolini) roam from their neorealist roots more than others (Rossellini, Visconti). But none are as elegantly unpretentious as De Sica. There is something noble, or endearingly unashamed, about his “one for me, one for them” pragmatism, his weakness for any old part, the lack of career-vanity or ego. He worked with some of the most beautiful women in the world, directed one of the most enduring pieces of art of modern times, squandered almost all the money he made on bets, and somehow stayed true to his political, sexual, religious and artistic principles. In The Garden Of The Finzi-Continis, Giorgio’s father says “to really understand the world, you must die at least once. So it’s better to die young, when there’s still time left to recover and live again”. Vittorio De Sica reincarnated himself so often that he lived several lives all at once and reaped the benefits of each. What could be more rakish than that?