Excess All Areas: Federico Fellini

In a month dedicated firmly to maximalism, The Rake commences a three-part exploration of the life and work of some undisputedly rakish individuals for whom understatement was a foreign concept.

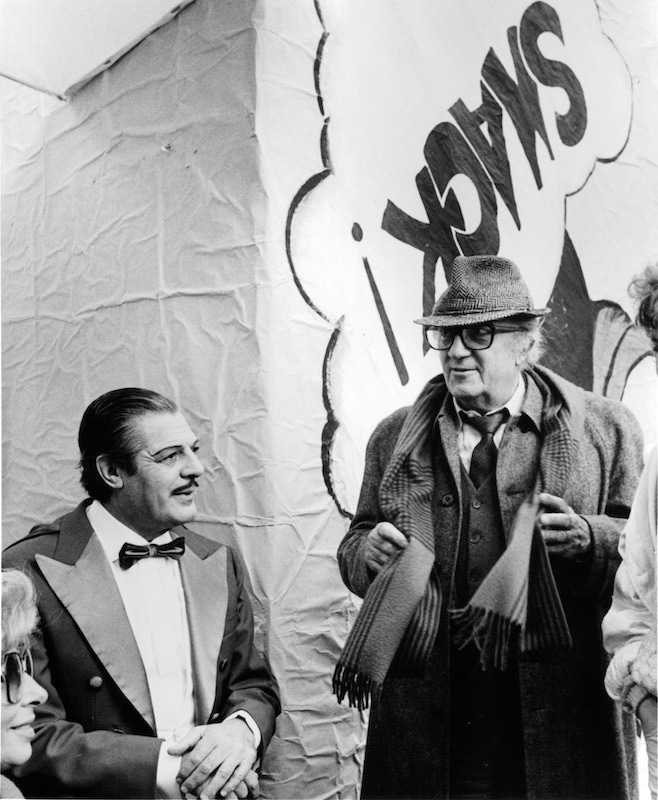

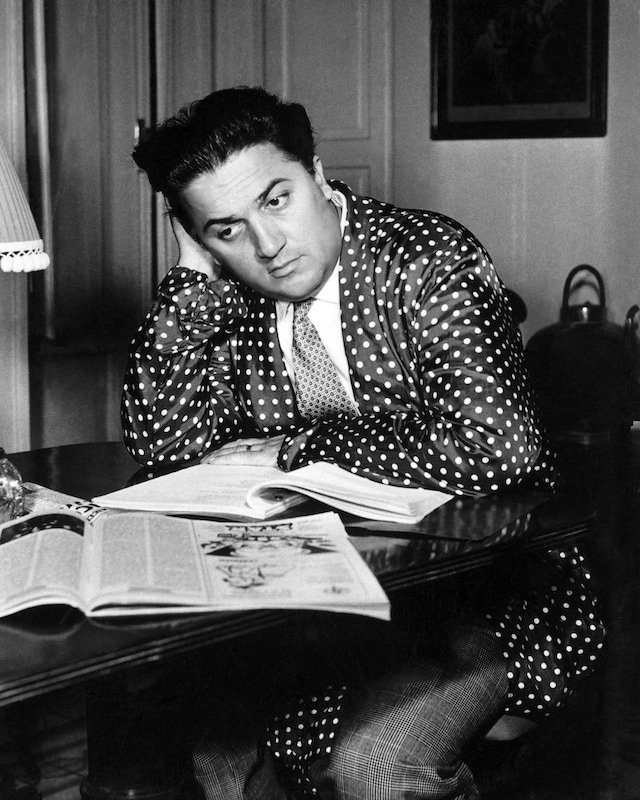

Federico Fellini was the most excessive Italian director of the twentieth century. In films packed with dreams, fantasy, surrealism, artifice and a sort of circus rococo, he created some of cinema’s most luxuriant images, the apogee Anita Ekberg’s dance in the Trevi fountain. Born into a middle-class family in Rimini, a town on the Adriatic coast that has since named its airport after him, Fellini poured an early infatuation with Grand Guignol and Dante into caricatures he drew and jokes he wrote for the satirical magazine Marc’Aurelio; at 19 he toured Italy with a vaudeville troupe, a year he considered the most important of his life. Conscripted into the Avanguardista (a compulsory fascist group for young men), the apolitical Fellini managed to evade the military draft with a gift for deceit he would sharpen over the decades.

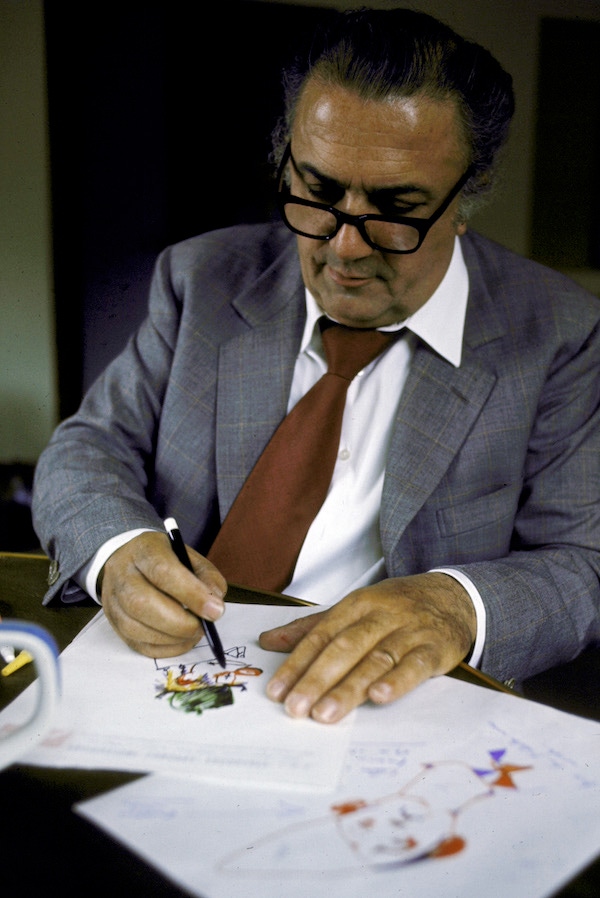

In 1945, Fellini broke through as a scriptwriter for neorealist master Roberto Rossellini on Rome, Open City, which Martin Scorsese has since called “the most precious moment of film history” (Jean-Luc Godard also quipped “all roads lead to Rome, Open City”). His screenplay was nominated for an Oscar (he eventually won five), but Fellini would lapse from neorealism, as ambivalent to Italian cinema’s accepted house style as he was to national politics, football and Catholicism. One biography suggests he wanted to give Paisà, his next collaboration with Rossellini, “the feel of a de Chirico landscape”. Gore Vidal thought him “essentially a painter rather than a narrative artist”, a theory borne out by Fellini’s own touchstones. “We must make a film like a Picasso sculpture”, he told fellow writer Tullio Pinelli. “Break the story into pieces, then put it back together according to our whim.”

A solipsistic perfectionist, he wrote all of his own scripts and claimed he didn’t need producers: “I need only a man who will give me money.” He obsessively rewatched his own films many times and rarely those of other directors (though he openly admired Buñuel, Bergman and Kurosawa). “Even if I set out to make a film about a fillet of sole”, he claimed, “it would be about me”. Though these days his canon is critically revered, at the time each new Fellini release met splutters of outrage, particularly in Italy. His producer on I Vitelloni (1953) called him a “sadist, and you like ugliness”. In La strada (1954), for which he won his first of five Oscars, he cast American actor Anthony Quinn as a strongman and his own wife, Giuletta Massina, as a little clown. He grew disenchanted with their social symbolism: previously clowns were the “caricature of a well-established, ordered, peaceful society. But today all is temporary, disordered, grotesque. Who can still laugh at clowns? All the world plays a clown now.” (Goodness knows what he’d make of the current spate of creepy clown sightings…)

His two most beautiful films, La Dolce Vita (1960) and Otto e Mezzo (1963), are highpoints of post-war Italian art. The former foams with class and iconoclastic imagery, like the statue of Christ dangled from a helicopter, but (like Saturday Night Fever) has a far darker tone than the glossy social movement it spawned; the film won the Palme d’Or, but Fellini was condemned as a “public sinner” and spat at in the street. From its extraordinary opening sequence, Otto e Mezzo, or 8½, deconstructs the romantic and artistic conflicts of a film director (played by Fellini’s on-screen alter ego Marcello Mastroianni) through a Jungian, dreamlike filter. After Otto e Mezzo won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, the imagery of Fellini’s films became even more deranged, with traces of parapsychology and the LSD he took under the supervision of his psychoanalyst. Satyricon (1969) spiced ancient orgies with beheadings and ephebophilia; the poster for Buñuelian vignette-romp Roma (1971) had a faceless woman on all fours with three rows of breasts; Amarcord (1973) featured a religious fashion show whose nuns roller-skate past cobwebbed skeletons; Donald Sutherland’s lusty old buffer in Casanova (1976) seduces a nun, a hunchbacked nymphomaniac and a mechanical doll.

Unsurprisingly, this outlandish virility coursed through his private life. Fellini was a notorious philanderer who referred to the "insatiable dragon" inside his trousers and claimed it was “easier to be faithful to a restaurant than it is to a woman”. One-time lover Germaine Greer, whom he cast in Casanova, said he turned up at her tiny Tuscan house and slipped into a pair of brown silk pyjamas with white piping. “Sexual athletes are tuppence a dozen. Fellini was a many-sided genius. I do not hope to meet his like again.” Every couple of hours he’d ring his poor wife Giuletta, whom he married in 1943 and who stayed with him until his death.

Indeed, Fellini was a consummate liar. Wary of journalists (and no coincidence that he named La Dolce Vita’s celebrity photographer Paparazzo after Italian slang for ‘mosquito’, a word now part of the international lexicon), he often teased their obsession with “meaning” and simplistic answers: he invented a story he'd run away to the circus as a boy (to “explain” his fondness for circuses) and joked “8½” was the age he lost his virginity. According to The Telegraph, he also told countless medical white lies to avoid social engagements: legs in plaster, accidents, a sick wife or mother, an ankle sprained at the airport, sudden dizzy spells and a number of heart attacks. He eventually died of a stroke at 73, on the same day as River Phoenix. Sophia Loren, who had presented Fellini with an honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement, said “a great light has gone out and now we are all in the dark”.

But are we, Sophia? Many of today's most distinctive innovators, from Terry Gilliam to David Lynch, are backlit with Fellini’s influence, what he called his “infinite passion of life”. According to his New York Times obituary (one so full of fine phrases it’s hard not to steal), Fellini likened his craft to applying a thermometer to a troubled world and finding a high fever. “I would like to be as good as nature, which with a shower produces flowers and grass to cover the destruction. But we are surrounded by human fragmentation, by pessimism, and it is difficult to talk of other things.” For him, all art was autobiographical: “the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.” His filmography is one of the gleaming capstones of modern European cinema, a ruby to Bergman’s obsidian and one that repeatedly fractured his own reflections. Federico Fellini was a tolerant overseer of sets of Babel, a poet who sang a song of himself, a dreamer who flew above the traffic jam of his peers, the Ahab of his own dolphin-torn imagination, and the ship sails on.