A Flair for Funk

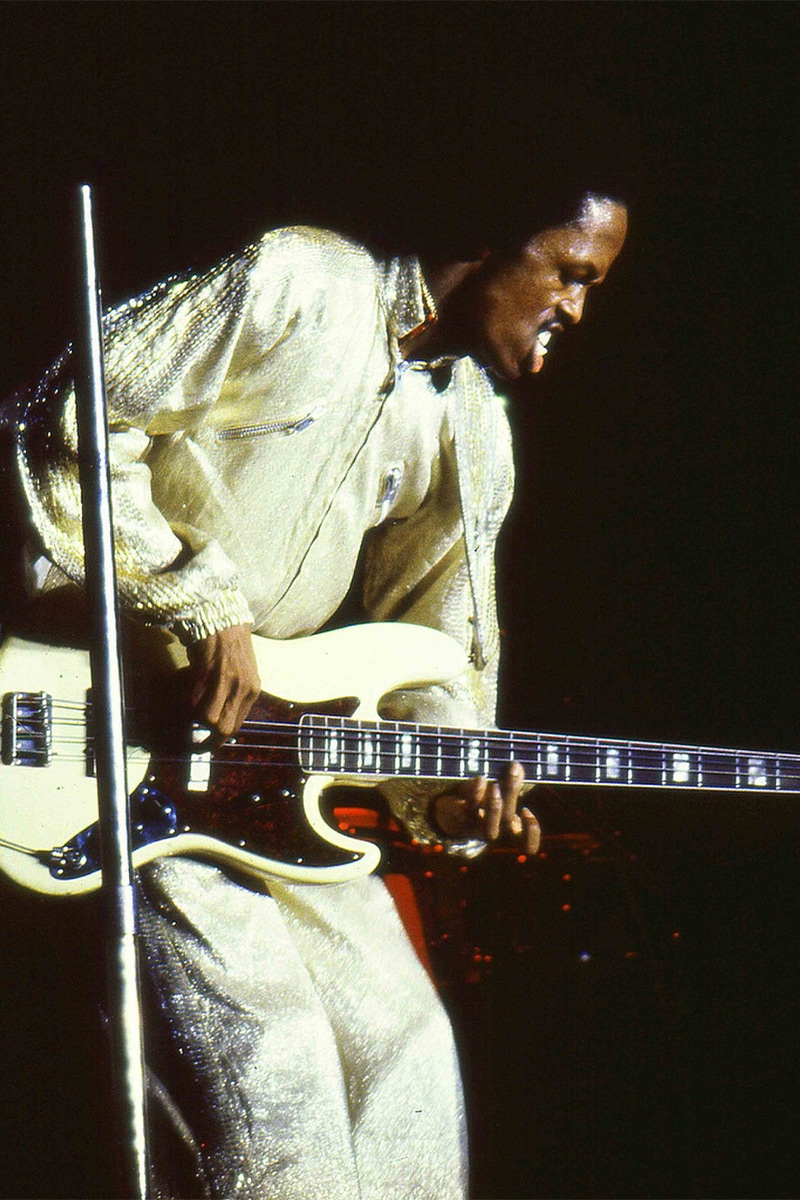

To understand the origins of funk, one must go back to James Brown. With its vivacious sound and sexuality, his 1967 record Cold Sweat is often cited by critics as the first funk record. But in his autobiography, Brown himself says that his sound changed in 1964, with Out of Sight. It was another beginning, Brown noted: “You can hear the band and me move in another direction rhythmically…” In this record, we can hear the birth of a groovy, and innovative, new beat. Unlike RnB, it isn’t driven by a series of chords, but instrumental interactions—Brown focused on the first downbeat in the rhythm (listen to the drums in 1971’s Make it Funky for a clearer example) and created a space where his vocals and the band could improvise. Brown was preaching to his audience, sometimes provoking them, and inadvertently seducing them. Like a lot of early rap music—and funk is the foremost influence of hip-hop—his lyrics were about being a hustler, a lady’s man, and in live performances they were usually dropped for moments of improvisation to ride the beat.

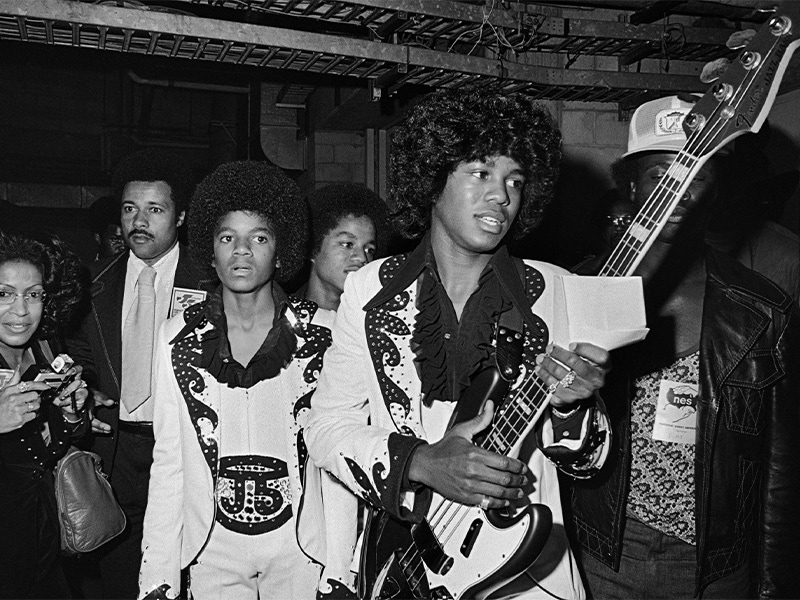

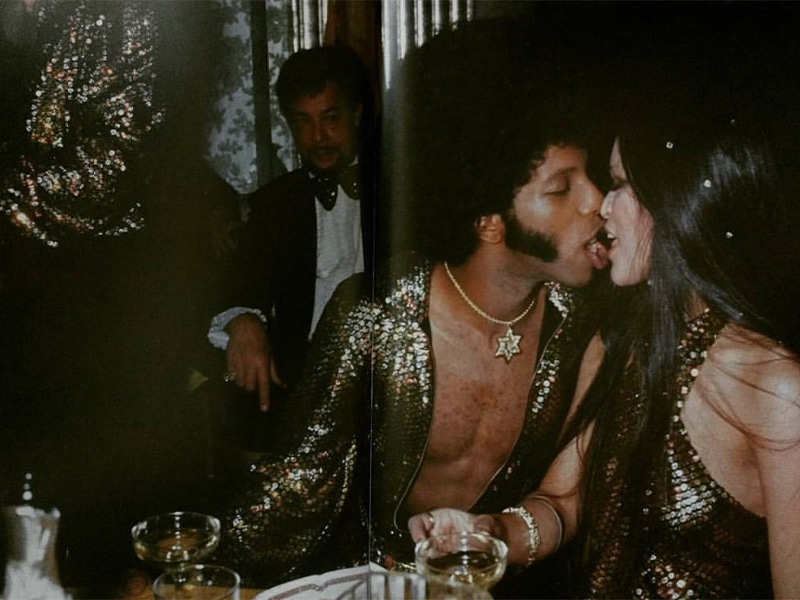

This sexuality would make funk music a dominant sound in the discos during the 1970s. There was a wave of groups following the template Brown had created, from Kool and the Gang, Funkadelic, Earth Wind and Fire, and The Brothers Johnson. But the sound would be pioneered again by Sly and the Family Stone, who would introduce psychedelic influences from rock-groups and the distinctive bass-slapping technique. As a group that represented a mix of different races, their lyrics called for peace, love, and progress in a post-Civil Rights America. Large mainstream social protest movements had faded by the late 60s and early 1970s, and so a counter-protest for change emerged through rhetorical means of funk music. James Brown’s The Black Panther Movement had the thrilling cry, ‘Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud’—while Sly and the Family Stone’s record There’s a Riot Goin’ On became the soundtrack for a divided and tense America—torn by police brutality, inequality, and the Vietnam War.

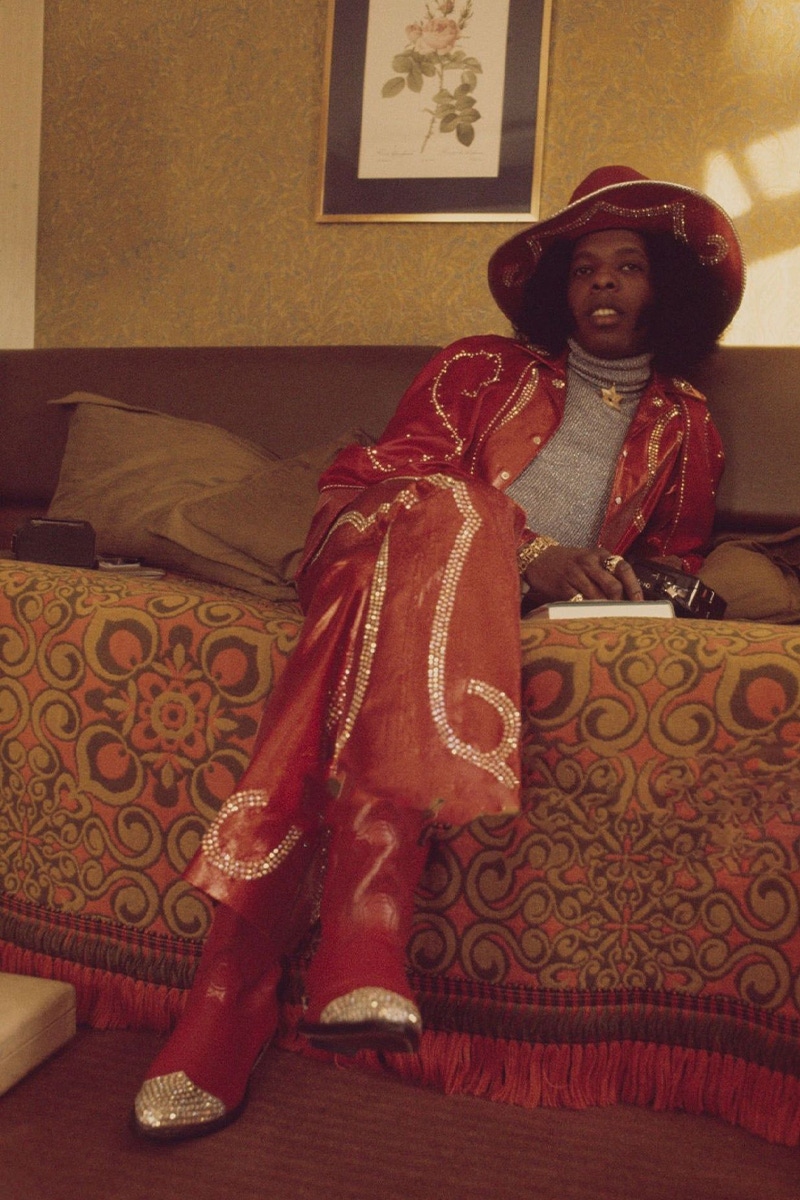

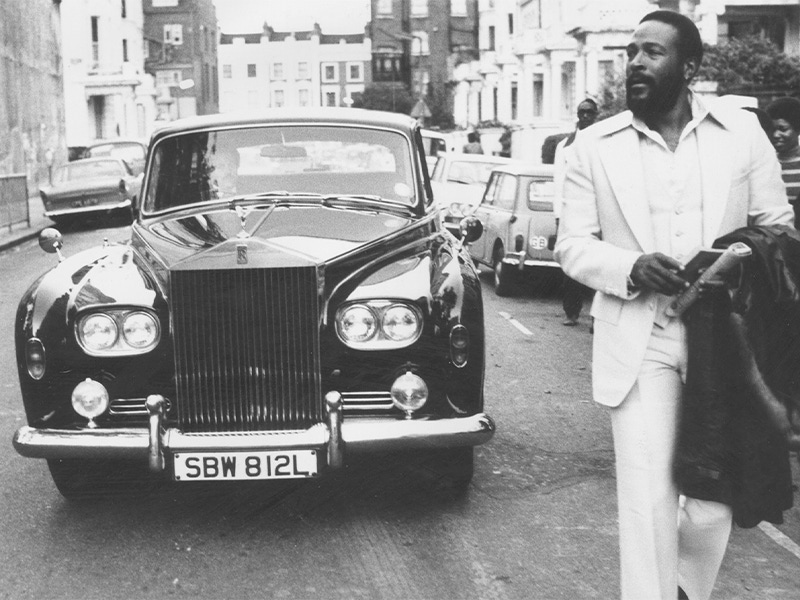

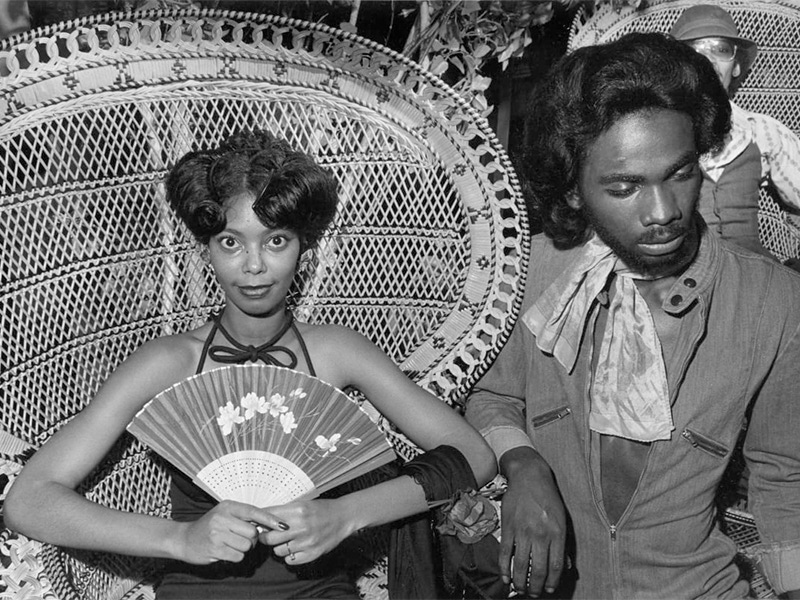

Young people began to emulate the fashions they saw on the funk record covers, political posters, and live on-stage. This was a less buttoned-up image than the Motown and soul singers of the decade, and there was an emphasis on extravagance, colour, and loud prints. As with funk lyrics, there was a sense of improvisation in the fashion—even though this was a group who intended to be seen as stylish on the streets and in the clubs. Flare trousers, silk shirts, flat-caps, and check-motifs were the image of a flourishing anti-establishment subculture who only allied themselves to the funky sound.

Cinema was paying attention to what was happening in funk music. Suddenly, a series of films were released that portrayed the tough and sexually-charged ‘soul brother’ character in Blaxploitation movies. The soundtracks for Supafly, Shaft, Foxy Brown, and Sweet Sweetback were funky and cool, and represented the contemporary sound for African-American stories on-screen—most of which depicted the racial inequalities in 1970s USA. The nature of these films were political. They showed empowered black people in a way that wasn’t being presented in Hollywood, and Blaxploitation cinema would later be homaged famously by Quentin Tarantino in Jackie Brown, which featured its own original funk score.

Funk resonated so successfully with all types of people that it would inspire music genres across the world. Afrobeat was a Nigerian melding of funk and local singing and rhythms. Many of the most prominent Disco music artists in the late 70s and 80s, including Chaka Khan and Barry White, had their origins in funk—songs like ‘Kung Fu Fighting’ and ‘Every Woman’ have funky bass sounds. But no genre is more inspired by the rhythms and freestyle approach of James Brown and his contemporaries than rap music. Today it is the largest genre in the USA, and is among the most popular all over the globe. In the early days of hip-hop, with the Sugar Hill Gang and Afrika Bambaataa, the MC spoke over danceable funk rhythms. Los Angeles G-Funk, by Dr Dre, Snoop Dogg and Tupac Shakur would follow in the 90s, once again introducing political themes to the otherwise-optimistic songs, bringing new light on police brutality and inequality, and becoming the soundtrack for a new wave of Black Panthers and activists.

Funk had its biggest, most recent hit with Pharrell William’s ‘Happy’—a song that trended globally in 2013 (and still reverberates in our ears now). This was a return to that classic, sexually-driven, optimistic sound from the 1970s, and artists like Mark Ronson and Bruno Mars would follow with another funk hit in 2018, the more obviously-titled ‘Uptown Funk’.

There is still something about the genre that persuades us to get up and dance or loosen up when they appear on the radio. When James Brown emphasised the first downbeat back in the 1960s, perhaps he couldn’t anticipate the way it would change how people dressed, spoke, and campaigned in America. It’s even less likely he understood the way it would take over the rest of the world. Funk music is more than a period of magic sandwiched nostalgically between jazz and hip-hop. It was the catalyst that made the magic happen.

Listen to The Rake Records, Volume Two

Now on Spotify.