Getting To Know Yul

Famed for his role as King Mongkut of Siam, which he played for over 30 years, it was perhaps inevitable that Yul Brynner also often expected the royal treatment in real life. Vain, demanding and arrogant, the flamboyant actor successfully channelled his charms and energies to great success both with the ladies and his tirelessly adoring audience.

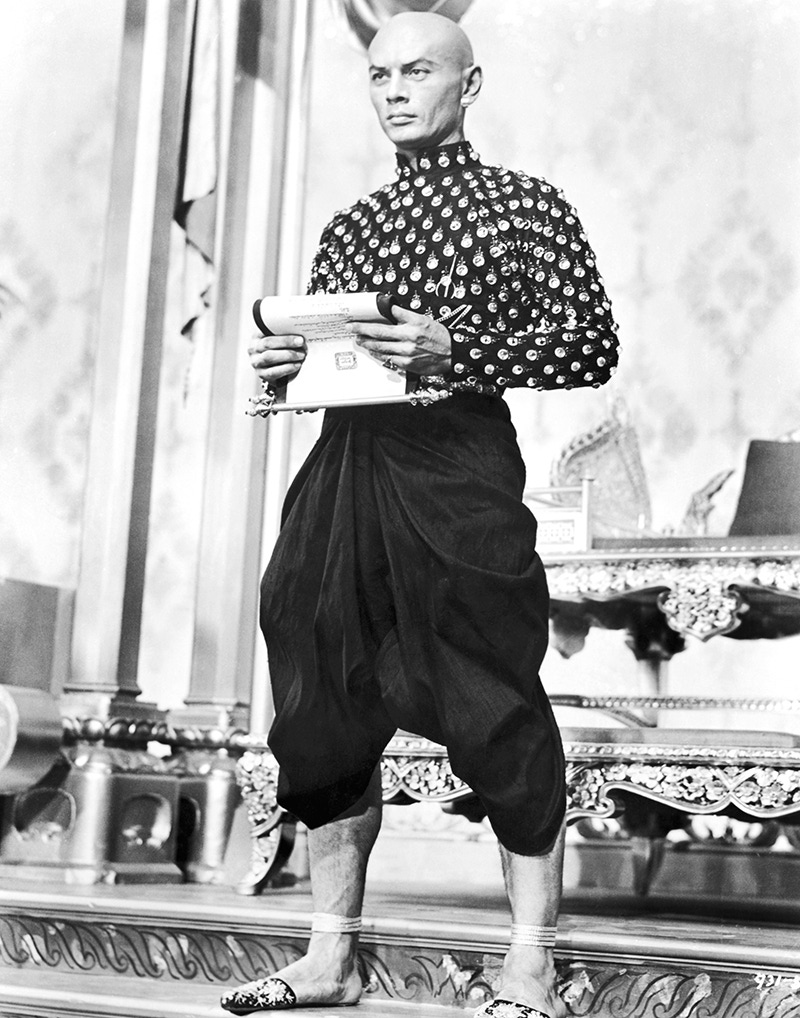

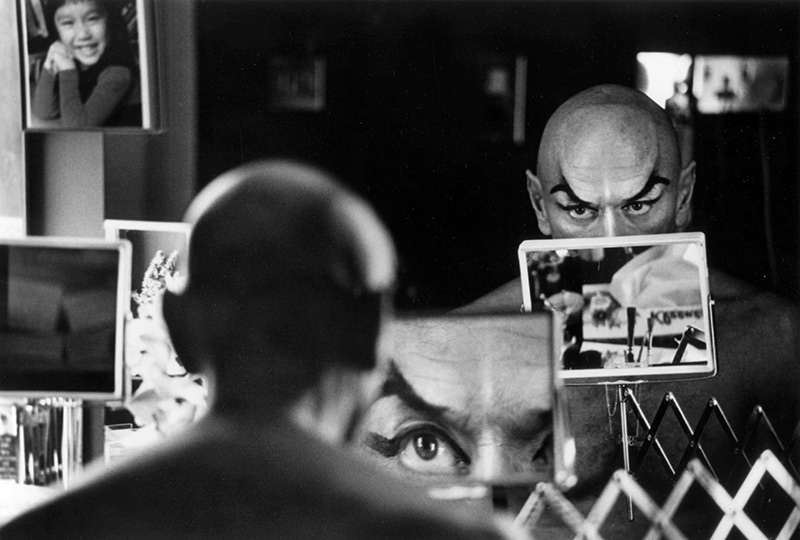

When, towards the end of his life, Yul Brynner was challenged to explain the conflicting accounts of the time and place of his origins that he'd given in almost every interview, he declared imperiously: 'Ordinary mortals need but one birthday.' The quote is an indication of how assiduously Brynner worked at burnishing his own legend. His name was already a byword for an outré kind of Hollywood exotica - he was the first shaven-headed movie idol, and his gimlet stare, precipitously arched eyebrows and all-purpose arcane mien saw him equally at home in bell-sleeved silk tunics (as the King of Siam in 1956's The King And I), pleated skirts and leopard-skin pashminas (as Pharaoh Rameses I in The Ten Commandments, released the same year), or the darkest outlaw double-denim (in 1960's The Magnificent Seven). In a rare moment of levity, he described himself as 'just a nice, clean- cut Mongolian boy'. He at least got the middle bit right.

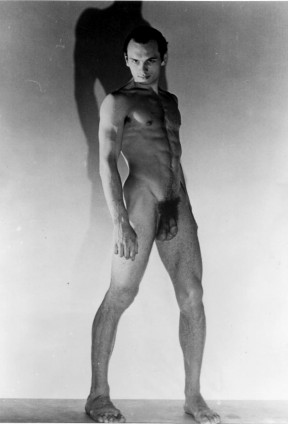

He was actually born Yuliy Borisovich Briner in 1920 in Vladivostok, of Swiss-Eurasian ancestry; his father was a mining engineer and his mother was a singer and actress. His malleable sense of identity - at times he called himself 'Julius Briner', 'Jules Bryner' or 'Youl Bryner' - was surely the product of a peripatetic childhood. His father abandoned the family when Brynner was three, and his mother took him and his older sister Vera to Manchuria, and later to Paris, where Brynner played Russian and Roma songs on his guitar in Russian nightclubs, worked as a trapeze artist with the touring Cirque d'Hiver (until a back injury put him out of commission), studied philosophy, and eventually, under the patronage of his best friend Jean Cocteau (their relationship sparked lifelong rumours of Brynner's bisexuality), joined a repertory theatre company. In 1940, the Brynners immigrated to the United States, and he enrolled in acting classes with the Russian teacher Michael Chekhov (nephew of Anton), whilst nude modelling for renowned photographer George Platt Lynes on the side; the pictures revealed that a more-than-generous endowment could be added to Brynner's swelling list of accomplishments.

By the mid-'40s, the buzz around Brynner was building: he married the first of his four wives, actress Virginia Gilmore, in 1944, and played a Chinese student named Tsai-Yong in the musical Lute Song on Broadway, alongside Mary Martin, a couple of years later. After a brief diversion directing shows for US TV - including a kids' puppet show with the deathless title of Life with Snarky Parker - Brynner was recommended by Martin for the role of King Mongkut of Siam in Rodgers and Hammerstein's new Broadway musical. The King and I was supposed to be a vehicle for Gertrude Lawrence as Anna, governess to Mongkut's children, but so indelible was Brynner's performance (and so incandescent his dome, newly depilated for the part) that his role was beefed up; he went on to play the part 4,625 times on stage over a span of 30 years, winning two Tony Awards, plus an Oscar for the 1956 film version. He even reprised the role in a short-lived TV reboot (Anna and the King) in the early '70s. Shall We Dance? was Brynner's big number, and his own answer was a resounding yes, not only embarking on an affair with Lawrence at the height of their joint success (whilst maintaining a concurrent affair with Marlene Dietrich), but also developing a robustly untrammelled ego. Rodgers and Hammerstein were fond of telling the story that, when Lawrence died during the run of the show and Brynner finally got top billing, he burst into tears at the news - of getting top billing. Meanwhile, Frank Langella, one of his later costars, opined in his memoir Dropped Names that Brynner was unmatched in his ability to wax lyrical about himself, adding, for good measure, that he was'never far from a full-length mirror'.

He was actually born Yuliy Borisovich Briner in 1920 in Vladivostok, of Swiss-Eurasian ancestry; his father was a mining engineer and his mother was a singer and actress. His malleable sense of identity - at times he called himself 'Julius Briner', 'Jules Bryner' or 'Youl Bryner' - was surely the product of a peripatetic childhood. His father abandoned the family when Brynner was three, and his mother took him and his older sister Vera to Manchuria, and later to Paris, where Brynner played Russian and Roma songs on his guitar in Russian nightclubs, worked as a trapeze artist with the touring Cirque d'Hiver (until a back injury put him out of commission), studied philosophy, and eventually, under the patronage of his best friend Jean Cocteau (their relationship sparked lifelong rumours of Brynner's bisexuality), joined a repertory theatre company. In 1940, the Brynners immigrated to the United States, and he enrolled in acting classes with the Russian teacher Michael Chekhov (nephew of Anton), whilst nude modelling for renowned photographer George Platt Lynes on the side; the pictures revealed that a more-than-generous endowment could be added to Brynner's swelling list of accomplishments.

By the mid-'40s, the buzz around Brynner was building: he married the first of his four wives, actress Virginia Gilmore, in 1944, and played a Chinese student named Tsai-Yong in the musical Lute Song on Broadway, alongside Mary Martin, a couple of years later. After a brief diversion directing shows for US TV - including a kids' puppet show with the deathless title of Life with Snarky Parker - Brynner was recommended by Martin for the role of King Mongkut of Siam in Rodgers and Hammerstein's new Broadway musical. The King and I was supposed to be a vehicle for Gertrude Lawrence as Anna, governess to Mongkut's children, but so indelible was Brynner's performance (and so incandescent his dome, newly depilated for the part) that his role was beefed up; he went on to play the part 4,625 times on stage over a span of 30 years, winning two Tony Awards, plus an Oscar for the 1956 film version. He even reprised the role in a short-lived TV reboot (Anna and the King) in the early '70s. Shall We Dance? was Brynner's big number, and his own answer was a resounding yes, not only embarking on an affair with Lawrence at the height of their joint success (whilst maintaining a concurrent affair with Marlene Dietrich), but also developing a robustly untrammelled ego. Rodgers and Hammerstein were fond of telling the story that, when Lawrence died during the run of the show and Brynner finally got top billing, he burst into tears at the news - of getting top billing. Meanwhile, Frank Langella, one of his later costars, opined in his memoir Dropped Names that Brynner was unmatched in his ability to wax lyrical about himself, adding, for good measure, that he was'never far from a full-length mirror'.

He was actually born Yuliy Borisovich Briner in 1920 in Vladivostok, of Swiss-Eurasian ancestry; his father was a mining engineer and his mother was a singer and actress. His malleable sense of identity - at times he called himself 'Julius Briner', 'Jules Bryner' or 'Youl Bryner' - was surely the product of a peripatetic childhood. His father abandoned the family when Brynner was three, and his mother took him and his older sister Vera to Manchuria, and later to Paris, where Brynner played Russian and Roma songs on his guitar in Russian nightclubs, worked as a trapeze artist with the touring Cirque d'Hiver (until a back injury put him out of commission), studied philosophy, and eventually, under the patronage of his best friend Jean Cocteau (their relationship sparked lifelong rumours of Brynner's bisexuality), joined a repertory theatre company. In 1940, the Brynners immigrated to the United States, and he enrolled in acting classes with the Russian teacher Michael Chekhov (nephew of Anton), whilst nude modelling for renowned photographer George Platt Lynes on the side; the pictures revealed that a more-than-generous endowment could be added to Brynner's swelling list of accomplishments.

By the mid-'40s, the buzz around Brynner was building: he married the first of his four wives, actress Virginia Gilmore, in 1944, and played a Chinese student named Tsai-Yong in the musical Lute Song on Broadway, alongside Mary Martin, a couple of years later. After a brief diversion directing shows for US TV - including a kids' puppet show with the deathless title of Life with Snarky Parker - Brynner was recommended by Martin for the role of King Mongkut of Siam in Rodgers and Hammerstein's new Broadway musical. The King and I was supposed to be a vehicle for Gertrude Lawrence as Anna, governess to Mongkut's children, but so indelible was Brynner's performance (and so incandescent his dome, newly depilated for the part) that his role was beefed up; he went on to play the part 4,625 times on stage over a span of 30 years, winning two Tony Awards, plus an Oscar for the 1956 film version. He even reprised the role in a short-lived TV reboot (Anna and the King) in the early '70s. Shall We Dance? was Brynner's big number, and his own answer was a resounding yes, not only embarking on an affair with Lawrence at the height of their joint success (whilst maintaining a concurrent affair with Marlene Dietrich), but also developing a robustly untrammelled ego. Rodgers and Hammerstein were fond of telling the story that, when Lawrence died during the run of the show and Brynner finally got top billing, he burst into tears at the news - of getting top billing. Meanwhile, Frank Langella, one of his later costars, opined in his memoir Dropped Names that Brynner was unmatched in his ability to wax lyrical about himself, adding, for good measure, that he was'never far from a full-length mirror'.

He was actually born Yuliy Borisovich Briner in 1920 in Vladivostok, of Swiss-Eurasian ancestry; his father was a mining engineer and his mother was a singer and actress. His malleable sense of identity - at times he called himself 'Julius Briner', 'Jules Bryner' or 'Youl Bryner' - was surely the product of a peripatetic childhood. His father abandoned the family when Brynner was three, and his mother took him and his older sister Vera to Manchuria, and later to Paris, where Brynner played Russian and Roma songs on his guitar in Russian nightclubs, worked as a trapeze artist with the touring Cirque d'Hiver (until a back injury put him out of commission), studied philosophy, and eventually, under the patronage of his best friend Jean Cocteau (their relationship sparked lifelong rumours of Brynner's bisexuality), joined a repertory theatre company. In 1940, the Brynners immigrated to the United States, and he enrolled in acting classes with the Russian teacher Michael Chekhov (nephew of Anton), whilst nude modelling for renowned photographer George Platt Lynes on the side; the pictures revealed that a more-than-generous endowment could be added to Brynner's swelling list of accomplishments.

By the mid-'40s, the buzz around Brynner was building: he married the first of his four wives, actress Virginia Gilmore, in 1944, and played a Chinese student named Tsai-Yong in the musical Lute Song on Broadway, alongside Mary Martin, a couple of years later. After a brief diversion directing shows for US TV - including a kids' puppet show with the deathless title of Life with Snarky Parker - Brynner was recommended by Martin for the role of King Mongkut of Siam in Rodgers and Hammerstein's new Broadway musical. The King and I was supposed to be a vehicle for Gertrude Lawrence as Anna, governess to Mongkut's children, but so indelible was Brynner's performance (and so incandescent his dome, newly depilated for the part) that his role was beefed up; he went on to play the part 4,625 times on stage over a span of 30 years, winning two Tony Awards, plus an Oscar for the 1956 film version. He even reprised the role in a short-lived TV reboot (Anna and the King) in the early '70s. Shall We Dance? was Brynner's big number, and his own answer was a resounding yes, not only embarking on an affair with Lawrence at the height of their joint success (whilst maintaining a concurrent affair with Marlene Dietrich), but also developing a robustly untrammelled ego. Rodgers and Hammerstein were fond of telling the story that, when Lawrence died during the run of the show and Brynner finally got top billing, he burst into tears at the news - of getting top billing. Meanwhile, Frank Langella, one of his later costars, opined in his memoir Dropped Names that Brynner was unmatched in his ability to wax lyrical about himself, adding, for good measure, that he was'never far from a full-length mirror'.

Brynner's triumphal arrogance was an essential part of his appeal, and he gave it free rein as he entered his imperial phase, both on and off screen. It survived intact through multiple indignities - from side ponytails to flannelette headpieces - in The Ten Commandments, and it burned up the screen in The Magnificent Seven, fuelled by Brynner's constant feuding with co-star Steve McQueen as to who was topmost dog. For one scene, Brynner fashioned a plinth of dirt to stand on so that he would tower over McQueen, only for the latter to surreptitiously kick a little more of it away each time he paced past (eventually, Brynner hired an assistant expressly assigned to call out any instance of McQueen's attempted scene-stealing). His demands became legendary - while filming the World War II drama Morituri aboard a freighter, he stipulated that a landing pad be built on the ship so that a private helicopter could take him ashore after each day's shoot. Likewise, he had a special lift installed in the theatre where The King and I played, big enough to accommodate his 20-foot-long white limo, to spare him the daily ordeal of rubbing shoulders with eager fans. His dandyishly-cut suits - all roped shoulders, generous lapels and jetted hacking pockets - emphasised his imposing figure and urbane air (he even gave his morning porridge a foppish twist, adding a chunk of butter and salt).

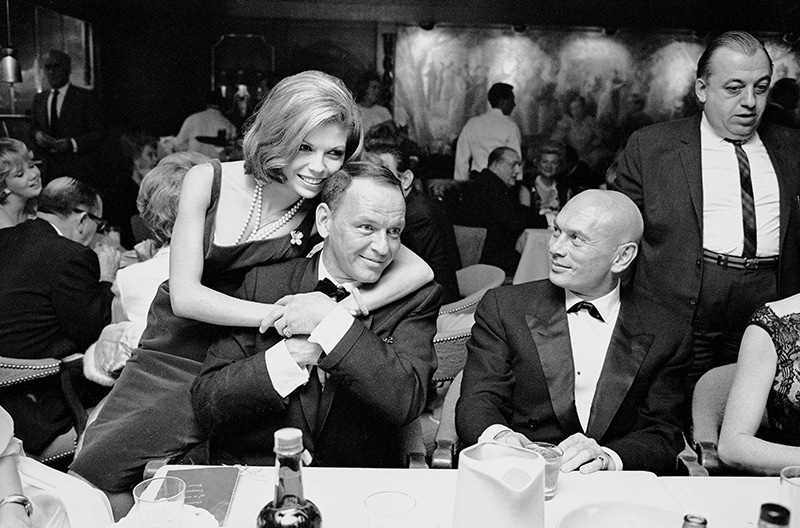

Brynner met his second wife, the Chilean model Doris Kleiner, on the set of The Magnificent Seven; she was a sleek, Balenciaga-clad contemporary of Marella Agnelli, Gloria Guinness and Lee Radziwill, and Brynner wooed her with a suitcase full of cashmere sweaters in multiple colourways. Their daughter, Victoria, had no less than Elizabeth Taylor as her godmother; Taylor was one of the subjects of the more than 8,000 photos Brynner took from the '50s through to the '70s, in both saturated colour and gritty black and white, of his co-stars and friends in moments of downtime (Frank Sinatra descending from a helicopter, Audrey Hepburn in a gondola). Many of the shots were used in magazine spreads or as studio-production stills, and exhibitions of Brynner's work have been mounted since his death (some at the behest of his friend and fellow photographer Karl Lagerfeld). Brynner's third wife, Jacqueline Thion de la Chaume, was a socialite and the Fashion Editor of French Vogue. She and Brynner adopted two Vietnamese children, Mia and Melody, and bought the 16th-century, 50-acre Manoir de Criqueboeuf in Normandy - the first house the nomadic Brynner had ever owned. His newfound domesticity encompassed the cultivation of bullfrogs and pigeons, and the keeping of penguins, as well as the planting of Oriental flora and the frequent entertaining of exotic fauna like Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin (Brynner became godfather to their daughter Charlotte).

Hollywood was changing radically in the '70s - gritty, character-driven vérité was in, and the larger-than-life fare in which Brynner thrived was out (with his brooding expressions and sinuous movements, one could almost make a case for him being the last silent-movie star). His final filmic hurrah was the sci-fi thriller Westworld (1973), in which he played a murderously malfunctioning robot; his all- black gear and steely-eyed automaton glare acted as a kind of valedictory tribute to his screen canon of ice-cool icons. He spent most of his final decade reprising Mongkut in endless tours and Broadway reruns of The King and I, and maximising merchandising opportunities therein with the likes of the not-at-all-clunkily-titled The Yul Brynner Cookbook: Food Fit for the King and You (including such regal treats as pork ribs and Strawberries Romanoff). A by-now-familiar story of continuing affairs and extended absences precipitated the breakup of his marriage to de la Chaume, and in April 1983, Brynner, then 62, married his fourth and final wife, Kathyyam Lee, a 24-year-old Malaysian ballerina who'd had a small part in The King and I's chorus line. Later the same year, he found a lump on his vocal cords - the test results showed that his throat was fine, but he had inoperable lung cancer (although Brynner had quit smoking the previous decade, he'd taken up the habit at the tender age of 12). Radiation therapy left him breathless and sidelined at the various performances that he insisted on honouring (the packed houses were a testament to his enduring popularity), but Brynner was quietly making his preparations for departure, embracing Buddhism and recording a dramatic public service announcement, to be broadcast after his death, warning of the dangers of nicotine ('Now that I'm gone, I tell you: don't smoke. Whatever you do, just don't smoke.')

Brynner eventually succumbed on 10 October 1985, in a New York hospital (the same day, curiously, as Orson Welles, with whom he'd co-starred in The Battle of Neretva; many commented on Brynner's unfortunate timing, and how he'd have hated playing second fiddle in the obit stakes). Following his death, his murky origins were finally enshrined by a statue erected outside his birthplace in Vladivostok's Aleutskaya Street. He stands, Social Realist hero-style, in a Mongkut- esque tunic and harem pants, shiny pate glinting in the evening sun. It's a singular figure, and one that - all his life - Brynner was proudly conscious of cutting. 'I have never played anyone I thought was like me,' he once said, with, one suspects, just the right amount of move-over-mere-mortal presumption.