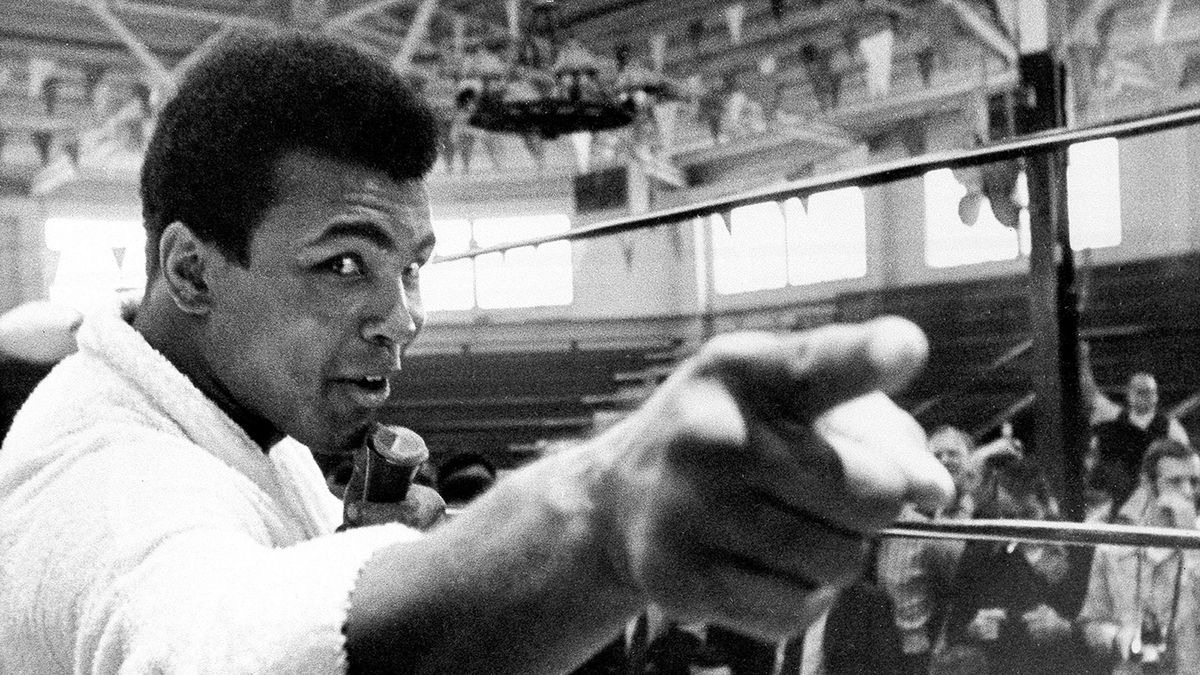

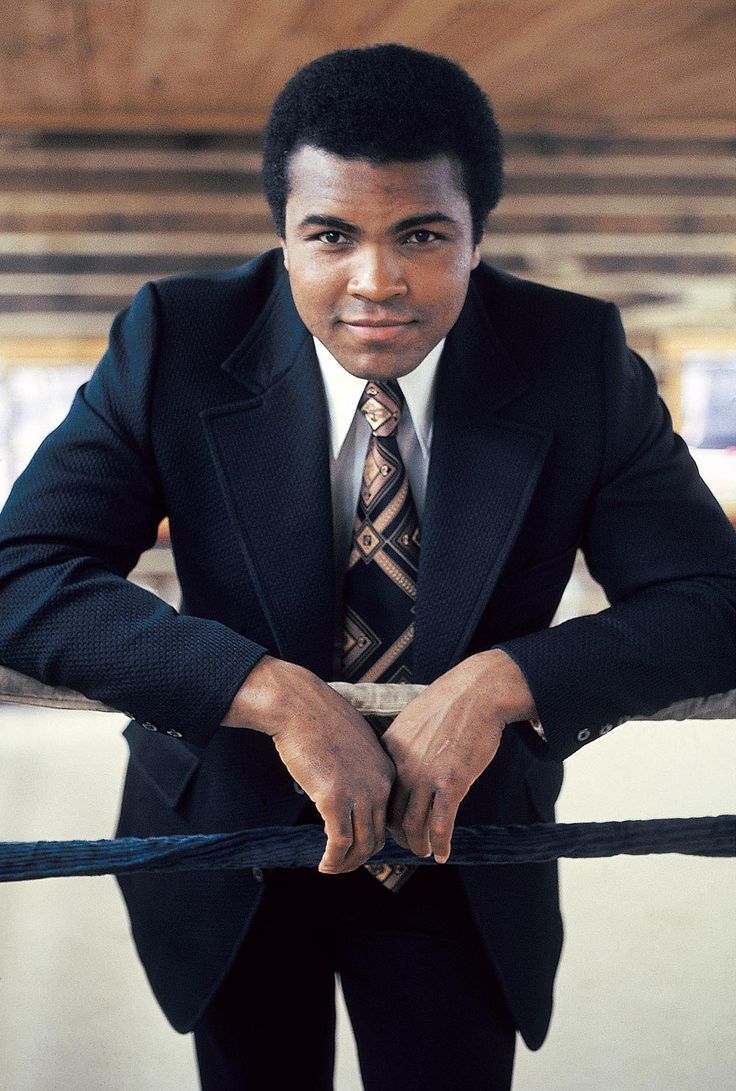

Heavyweight Gamechanger: Muhammad Ali

The Rake pays tribute to Muhammad Ali, one of the most influential sportsmen of the century.

“Impossible is just a big word thrown around by small men who find it easier to live in the world they’ve been given than to explore the power they have to change it. Impossible is not a fact. It’s an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It’s a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.”

It’s hard to overstate the profundity of these words. Particularly when they are the words of a man who lived the life that Muhammed Ali did. Born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. in Kentucky in 1942, Ali’s life was one characterised almost entirely by unimpeachable triumphs over adversity. The child of a billboard painter and household domestic, his childhood was a simple and happy one, shared with his sister and four brothers. He discovered boxing young and began training to compete at 12 years of age, racking up a series of amateur victories throughout his teens. It was apparently a Louisville police officer who put him on to the sport, upon discovering the young Cassius kicking a wall and cursing another boy who’d stolen his bike. Declaring to the officer that he’d give the boy a good “whupping” when he caught up with him, the policeman suggested to Ali that he ought to learn to box first. The idea evidently stuck.

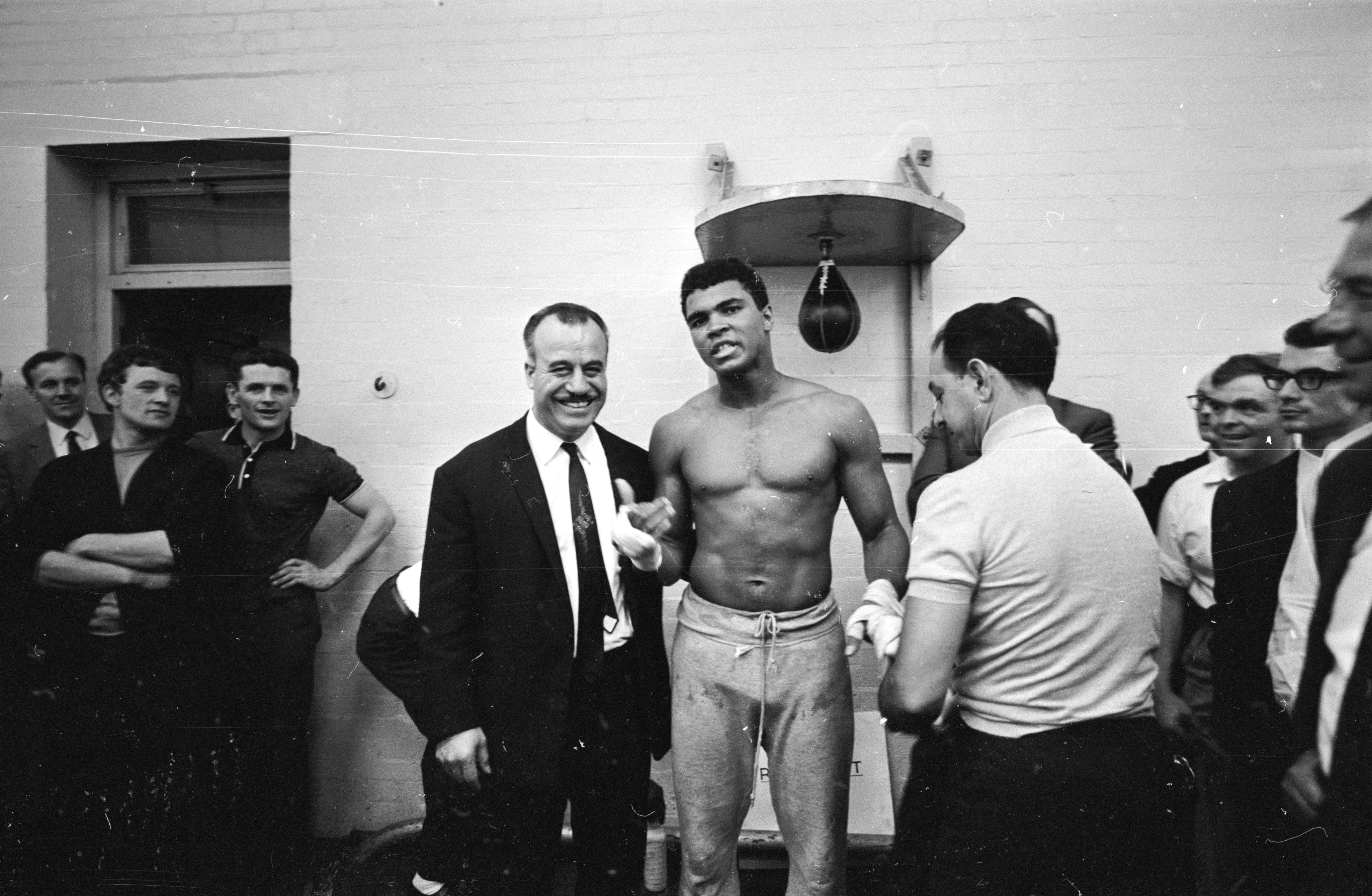

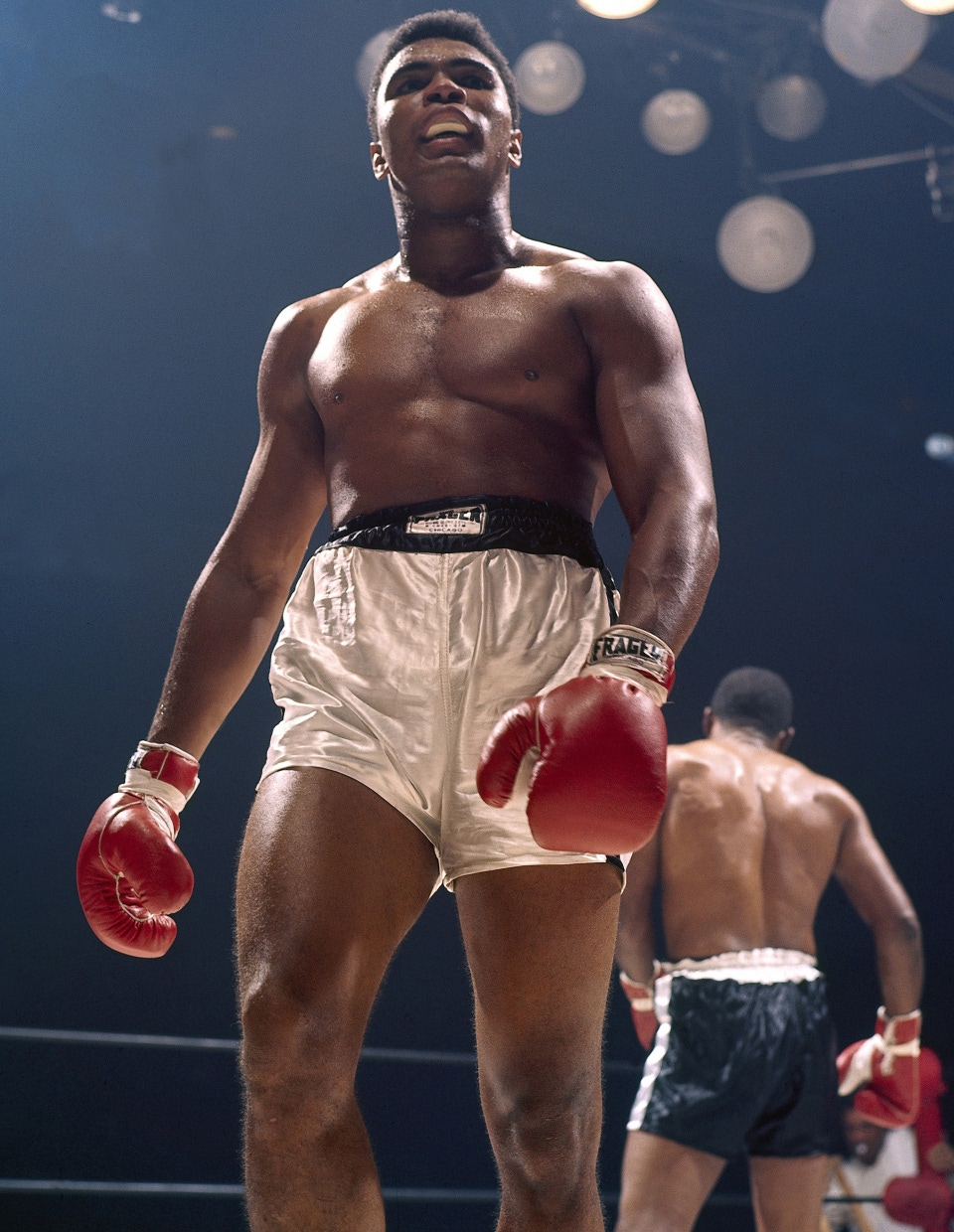

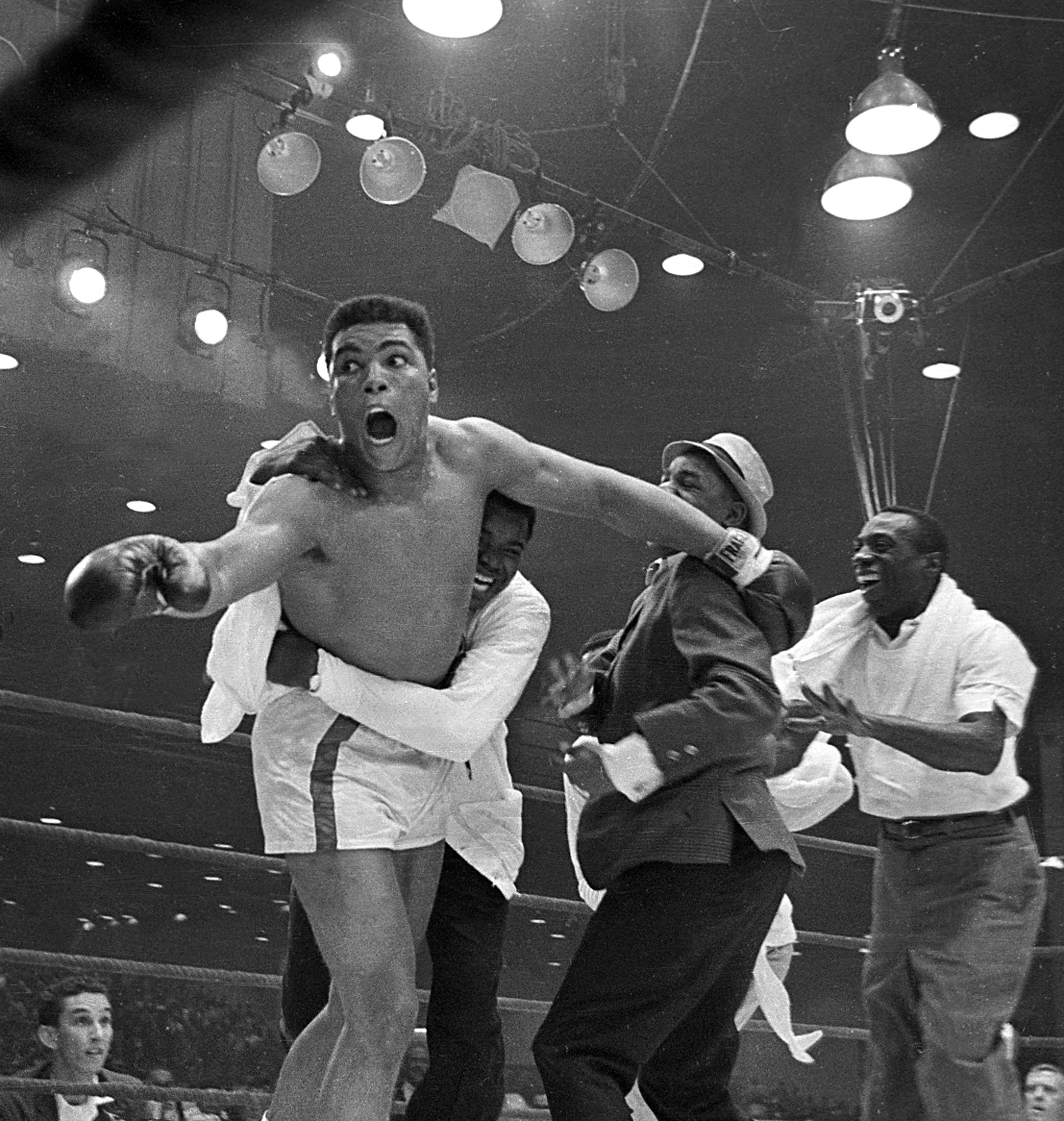

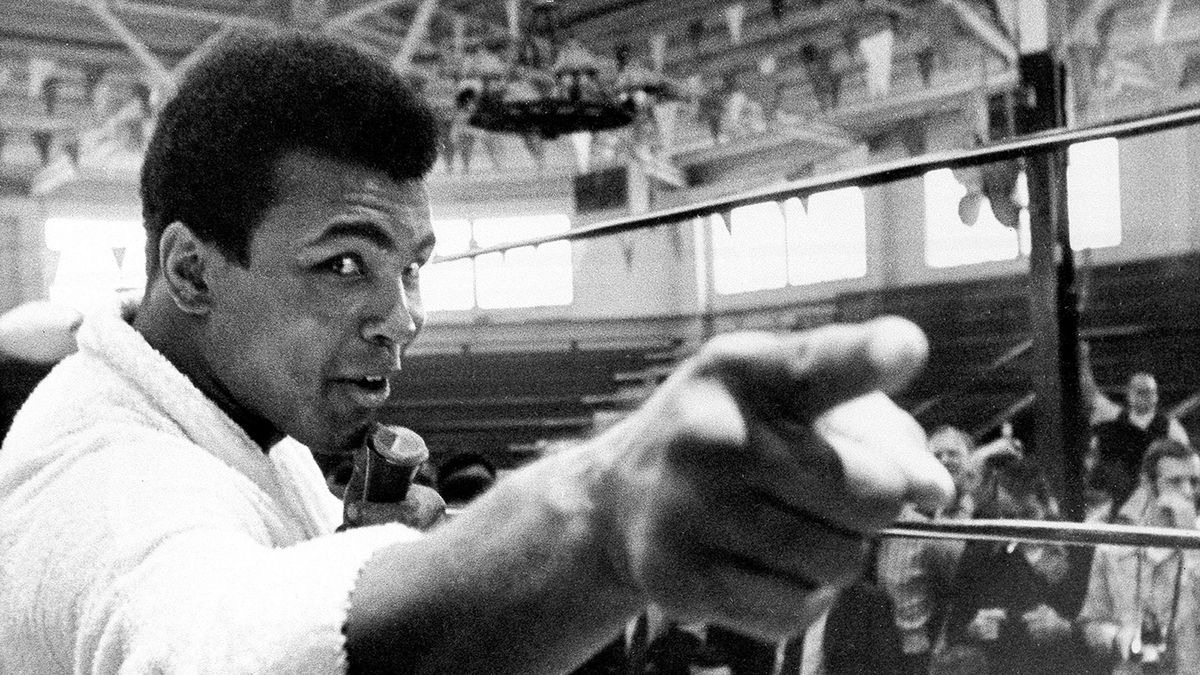

"He combined an extraordinary humility and deep religious sensitivity with a controversial sense of bravura."The achievements of his boxing career are of course the stuff of legend, and almost too numerous to bear repeating here; three times World Heavyweight Champion (the first at the tender age of 22 no less), in the two years before this, he amassed a record of 19–0 with 15 wins by knockout. In addition to his three hard-won World Heavyweight Titles, he can lay claim to beating just about every notable Boxer of the past sixty years; he felled major rival Joe Frazier three times and bested George Foreman during the iconic ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ by knockout in the 8th round, retaining his titles in the process. In 1999 he was awarded Sportsman of the Century by Sports Illustrated and Sports Personality of The Century the BBC. Small wonder then that he should be nicknamed simply as ‘The Greatest’ in recognition of his many quite phenomenal achievements inside the ring. He was also of course known as ‘The People’s Champion’, and it is arguably his life surrounding these professional triumphs that reflects the strongest elements of his personality. He combined an extraordinary humility and deep religious sensitivity with a controversial sense of bravura and unashamed amour propre. He popularised the notion of ‘talking tough’ in sport, and verbally intimidating his opponents became a powerful psychological weapon for Ali. Before taking-on the utterly terrifying Sonny Liston for his first attempt at the World Heavyweight title, Ali dubbed him the “big ugly bear” and caused no small amount of stir in proclaiming “after I beat him I’m gonna donate him to the zoo”. Let’s bear in mind here that Liston was not only a phenomenal physical specimen, but he was also a dominating personality with a shadowy past and ties to organised crime – not a man to be taken lightly.

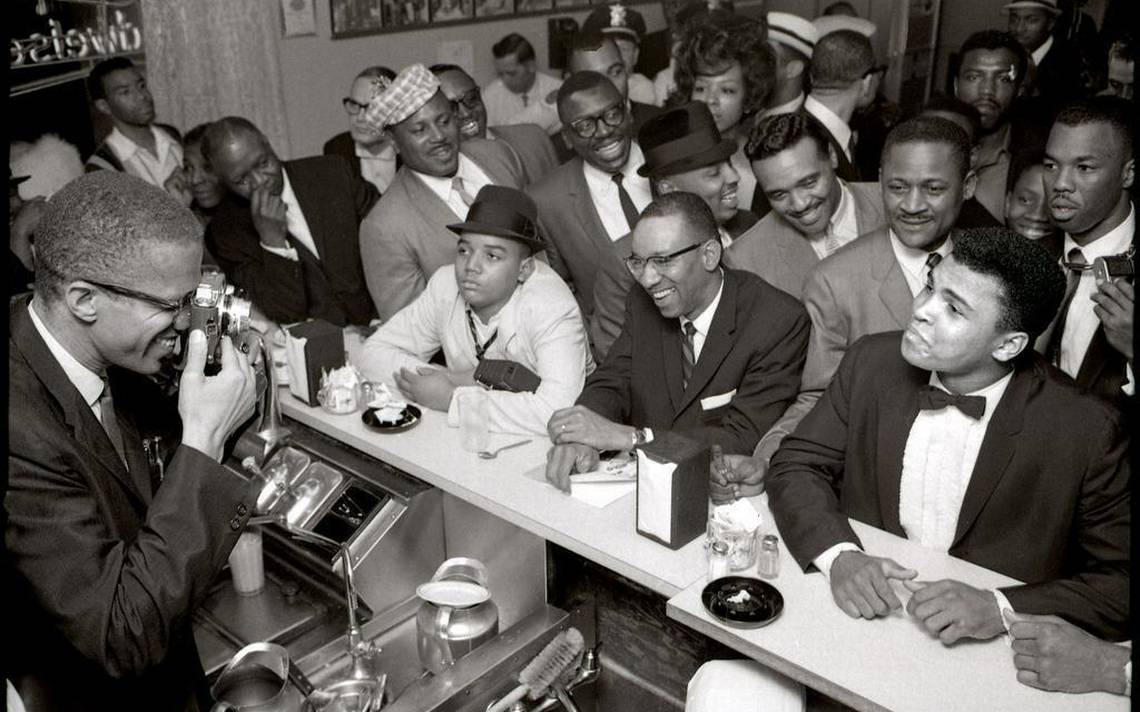

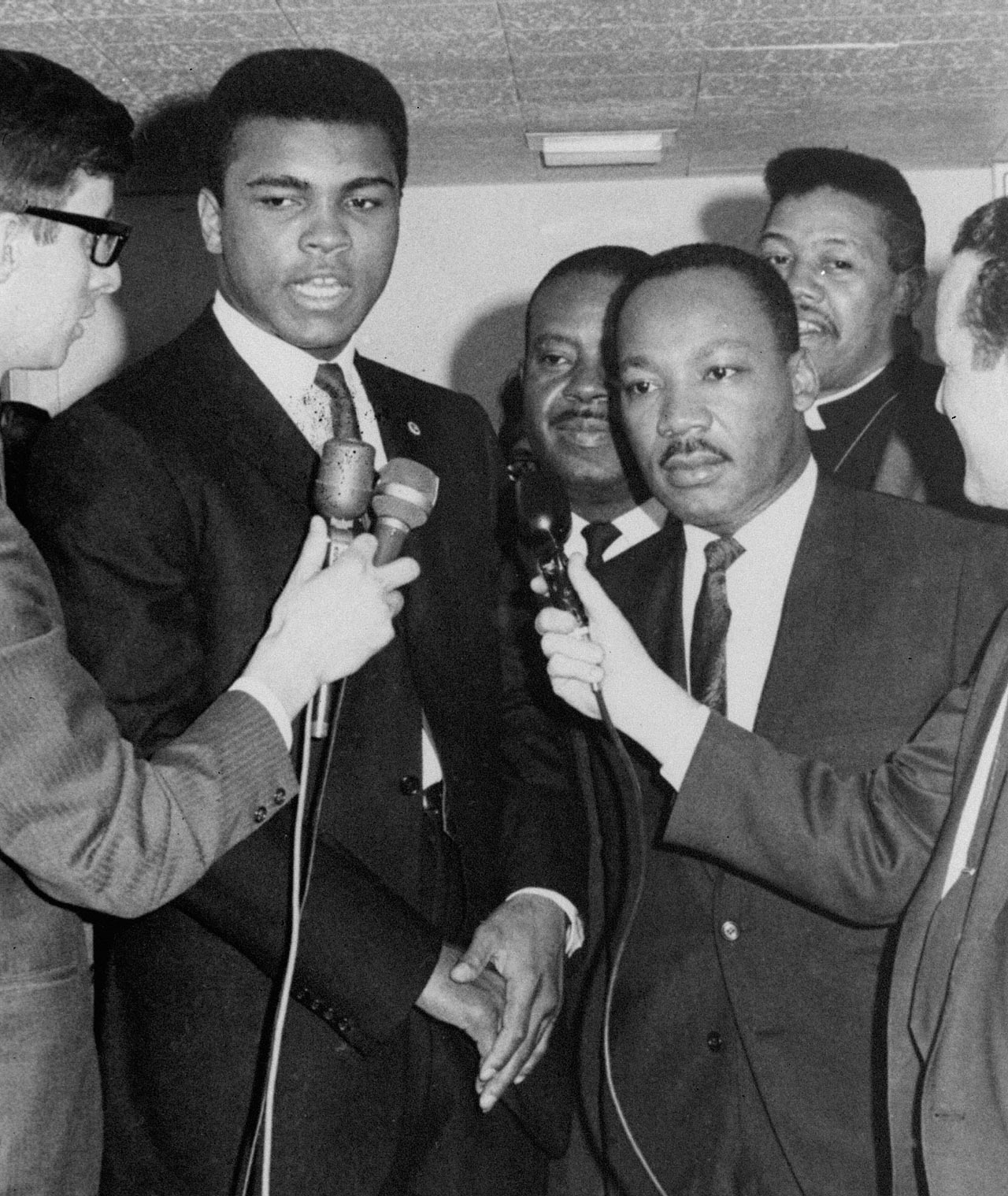

But Ali’s strength of personality more than showed through, and he became an icon not only for his extraordinary sporting achievements, but for his willingness to stick his head above the parapet for those issues of the day which mattered the most to him. Shortly after his first fight with Liston, Ali converted to Islam upon joining the Nation of Islam – an organisation founded in Detroit to work for ‘the spiritual, mental, social, and economic condition of African Americans in the United States and all of humanity’ – but which nonetheless brought with it a definite political dimension, care of the NOI’s leading proponent Malcolm X, who was to become Ali’s long-time political and spiritual mentor. Ali’s religious beliefs became inextricably interlinked with his politics in subsequent years and his influential voice was lent both to the sensitive subject of African-American civil rights, and famously to the Vietnam War.

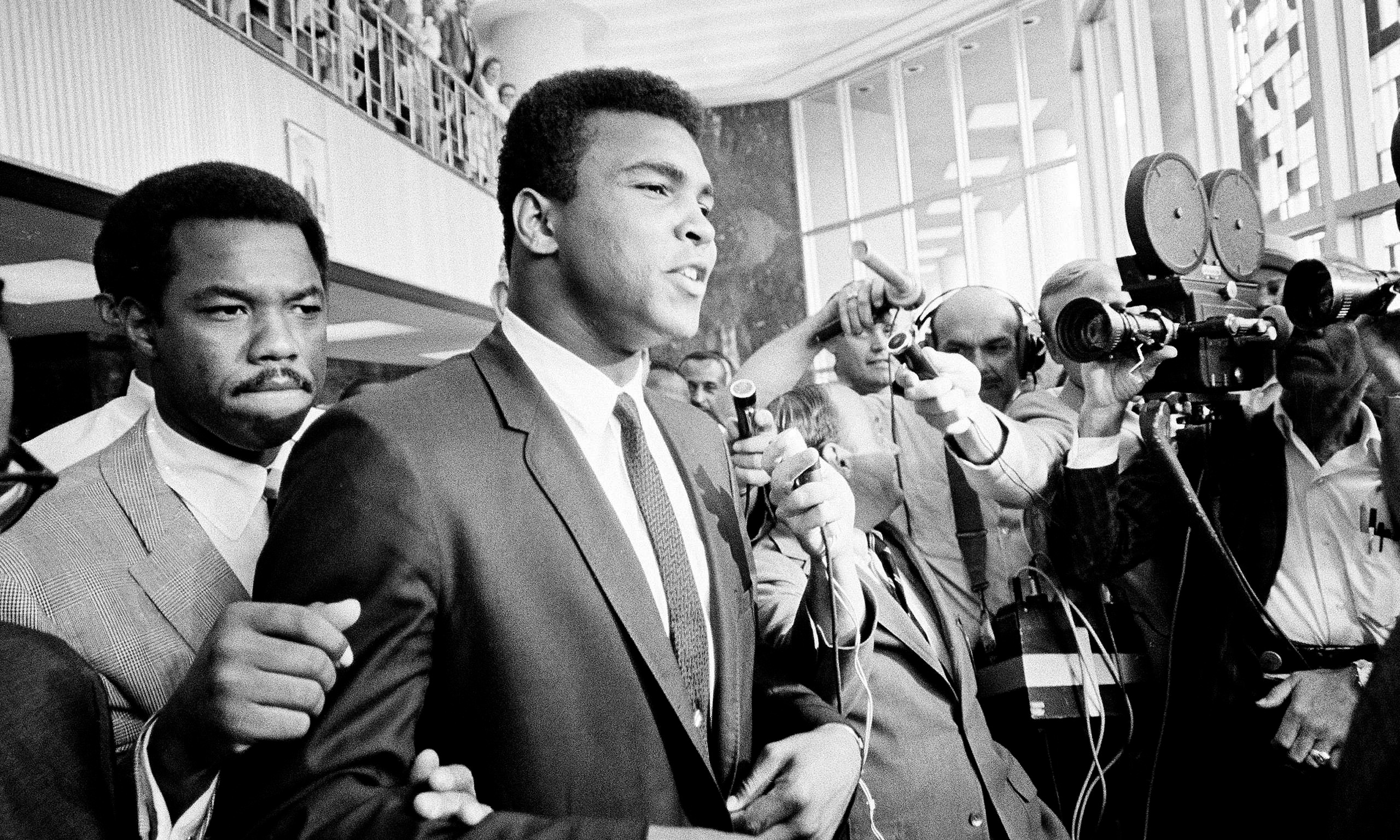

He refused to enlist in the American armed forces on the basis that “my conscience won't let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me ni***r.” The state’s response was to strip him of his titles, suspend his boxing licence and convict him of draft evasion. He was sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. He paid a bond and remained free while the verdict was being appealed – but he was unable to box for almost four years whilst his case worked its way through the appeals courts. To quote a cliché though, he was down but not out – in 1971 at the age of 29 he came back swinging – as the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in a unanimous 8-0 ruling (even Thurgood Marshall recused himself, as he had been the U.S. Solicitor General at the time of Ali's conviction). Here again, it seems that Ali’s forthright ambition and unimpeachable steadfastness allowed him to win through.

"His ability to take an unequivocally rakish stand was awe inspiring, and touchingly it seems to have made many a friend of an enemy."This steadfastness seems in large part to have been the trait which his competitors and fans alike found most endearing – his ability to take an unequivocally rakish stand was awe inspiring, and touchingly it seems to have made many a friend of an enemy. In 1996 for example, Ali had trouble walking to the stage at the 1996 Oscars to be part of the group receiving the Oscar for When We Were Kings, a documentary of the fight in Zaire, due to his Parkinson's disease. His famed opponent George Foreman helped him up the steps to receive the Oscar in what could be one of the most touching and gentlemanly acts of professional twentieth century sportsmanship. The simple fact is this. He was participating in arguably one of the most brutal and thuggish sports he could have chosen, and yet at all times outside of the ring he retained a very deep sense of gentility for the world around him – and for his fellow man. Tender images of him kissing his baby granddaughter days before his death speak volumes about the man’s sensitivity and decency. Ali was in every sense much more than a sportsman, he was a polymath; a great fighter, spokesman and a living testimony to the values of ambition, toil and an unwavering commitment both to sport, his religious beliefs and his fellow man. He put boxing on the map, spoke out for peace and for civil rights, he even taught himself to read and write. The instant global reaction to his death, and out-pouring of heartfelt tributes to him is as clear an indication of his influence as anything else could be. So permit The Rake to add one more tribute to his swelling tide – Muhammad Ali is undoubtedly one of the most rakish sportsmen of the century.