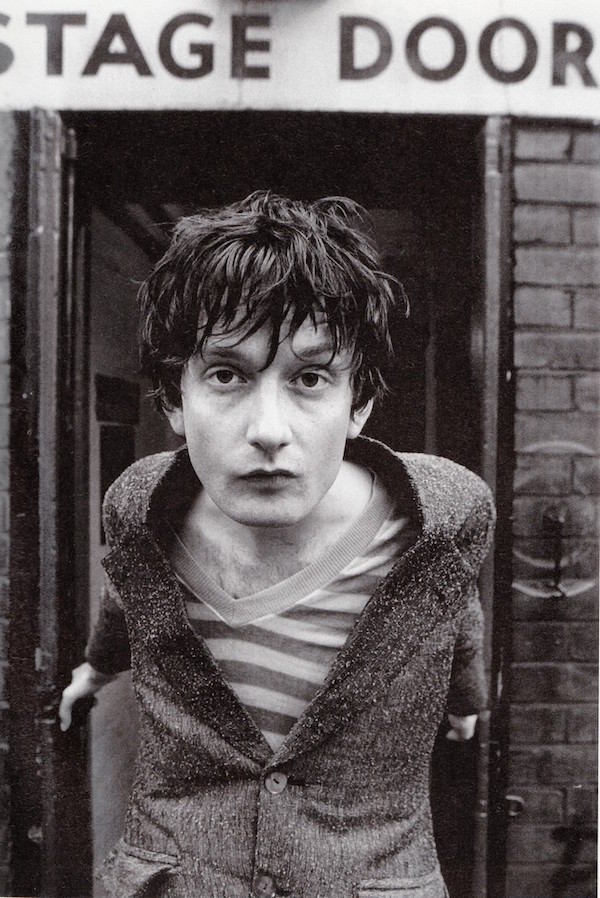

Jarvis Cocker: A Different Class

"The great thing about music is that anybody can do it", Jarvis Cocker once said. But if Cocker is the one setting the bar, we'd hate to test the theory of Pulp's lyrical frontman.

If Arctic Monkey Alex Turner is the semi-ironic Elvis of Sheffield, Jarvis Cocker is the city’s Gainsbourg. As the talisman of Pulp, the nineties English band who've aged the best, he wrote songs soothed in wit and brittled with erotic honesty. Lyrics dragonfly between the city and the country, steel and flowers, as attuned to the Yorkshire badlands as the Chateau Marmont, the luxury LA hotel that inspired the new album he released last week – an ideal chance to reappraise his influence.

In a decade reductively defined by Britpop, Cocker was a natural heir to Morrissey, a fey, playful, literary Northerner who brushed black diamonds of pessimism with a humour some missed. Having formed in 1978, Pulp didn’t really break through until 1994 with their fourth album His’n’Hers, whose tone coalesced romantic nostalgia with a regret for things before they’d happened: while ‘Happy Endings’ shivers and swoons, ‘Do You Remember The First Time?’ bites and teases. The band won the Mercury Prize for their next album Different Class, on which satire of poverty tourism (‘Common People’) meshed with low-key hedonism (‘Sorted For E’s and Whizz’).

Cocker’s voice on This Is Hardcore, Pulp’s masterpiece, eroticizes even the least promising subjects (‘Seductive Barry’ might be the sexiest song they made). For their last studio album before they split, the Scott Walker-produced We Love Life, Jarvis market-traded the urban for the pastoral, a summer field of sowthistles and cowslips seeded with weyrd-English absurdism. Beside the grassy cover art, the track-titles alone tell a grim narrative nature-cycle (‘Weeds I’, ‘Weeds II’, ‘Wickerman’, ‘The Trees’, ‘Birds In Your Garden’, ‘Roadkill’, ‘Sunrise’).

Noel Gallagher once admitted that lyrics were so low on his list of musical priorities that he often just chose words that had the right number of syllables to suit the tune. Not so Cocker, whose lyrics are so dense and evocative that Faber published a collection of them, blurbed with favourable comparisons to fellow Faber poets Larkin and Betjeman. In the pantheon of sex-lyricists, only Leonard Cohen (a hero of Cocker’s) comes close: “Still you’ve bought a toy to reach the place that he never goes”. Or: “She doesn’t have to go to work / But she doesn’t want to stay in bed / ‘Cos it’s changed from something comfortable / To something else instead”. Of his recent solo fare, the imagery of certain songs (‘Tearjerker’, ‘Salomé’) is more cryptic than others (‘Fuckingsong’, ‘Homewrecker!’), but here he is in his withering pomp, likening his ex’s new boyfriend to a ‘Bad Cover Version’ of himself:

“It's like a later Tom and Jerry

when the two of them could talk;

like the Stones since the eighties;

like the last days of Southfork

Like Planet of the Apes on TV;

the second side of 'Til the Band Comes In;

like an own-brand box of cornflakes

he's going to let you down my friend.”

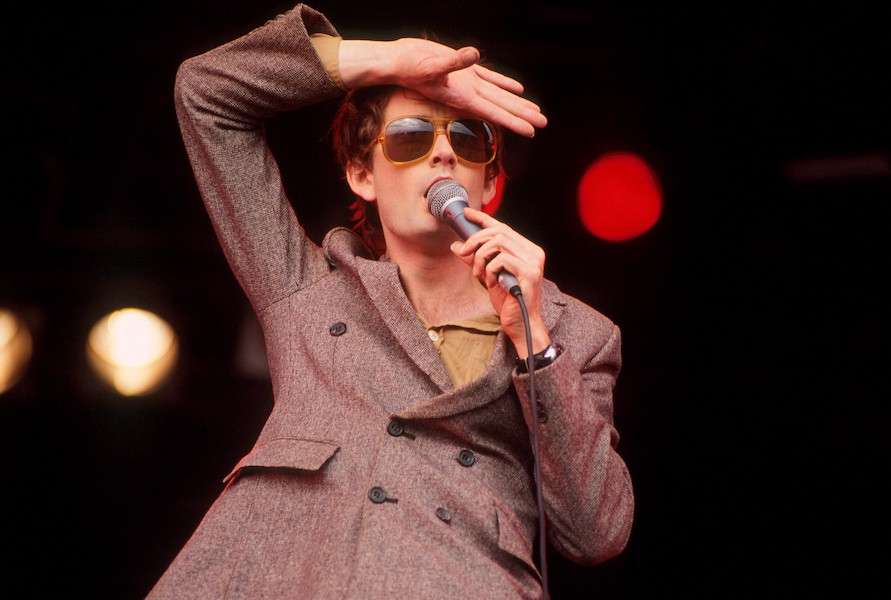

Unpretentious polymath and scruffy-chic enigma, Cocker occupies a unique position in the national consciousness. He wears middle age particularly well, the tweed-and-beard seamless accessories to the 6ft 4in figure, vintage specs and tousled mischief. In 1985, he fell out of a window when he pretended to be Spiderman to impress a woman. At the 1996 Brit Awards, he was so appalled by Michael Jackson’s performance of ‘Earth Song’, which Jackson played as a Messiah surrounded by children, that he took to the stage and mooned in protest. Although Cocker’s own following is quasi-religious, he refuses to navel-gaze: “I’d rather suck off a dog’s knob than listen to one of my own records”.

Francophile to the core, he dated actress Chloe Sevigny in the nineties, has lived in Paris with stylist Camille Bidault-Waddington (the mother of his son), contributed to Air’s Pocket Symphony, covered Serge for Monsieur Gainsbourg Revisited and even fronted a campaign for Eurostar. A Fine Art and Film graduate of Central St Martins (the London art school he immortalised in ‘Common People’), he has directed a music video for Aphex Twin, acted for Wes Anderson, worked as an editor-at-large for Faber, curated London’s Meltdown Festival, chaired last year’s Mercury Prize jury, hosted an award-winning Sunday Service radio show for BBC 6 Music and (alongside former Pulp guitarist Richard Hawley) fronted a campaign to save Sheffield’s trees.

Now he returns to his own music with Room 29, a “song-cycle” inspired by a suite at the Chateau Marmont with a piano in it. It’s a pared, soulful piece with the usual ashes of humour, a collaboration with Canadian musician Chilly Gonzalez, whom he met at a metro station after Cocker had been to the cinema to see Borat.

In the 2014 documentary Pulp: A Film About Life, Death and Supermarkets, Cocker compares his stage outfit to a suit of armour. It’s apt, as Jarvis has something of the aging knight about him, though he’s no deluded Quixote. Kitchen-sink surrealist, clear-eyed troubadour, urban naturist, a Gainsbourg cover even better than the original, he is the poet laureate of class-shadowed bedroom politics who, at 53, may just be hitting his prime.