Jean Genius: Jean Cocteau

Not only one of the greatest, most multi-talented creative minds of the 20th century, Jean Cocteau evinced elegance in every move, mode and mannerism.

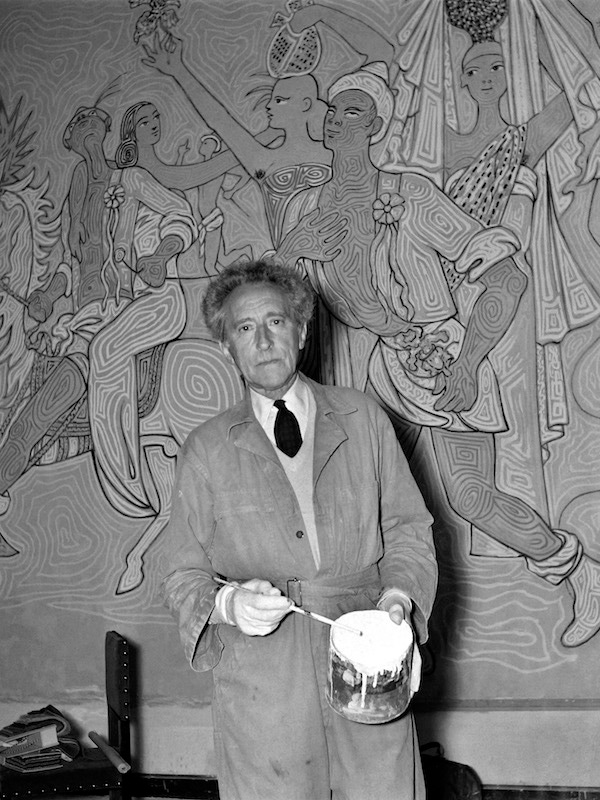

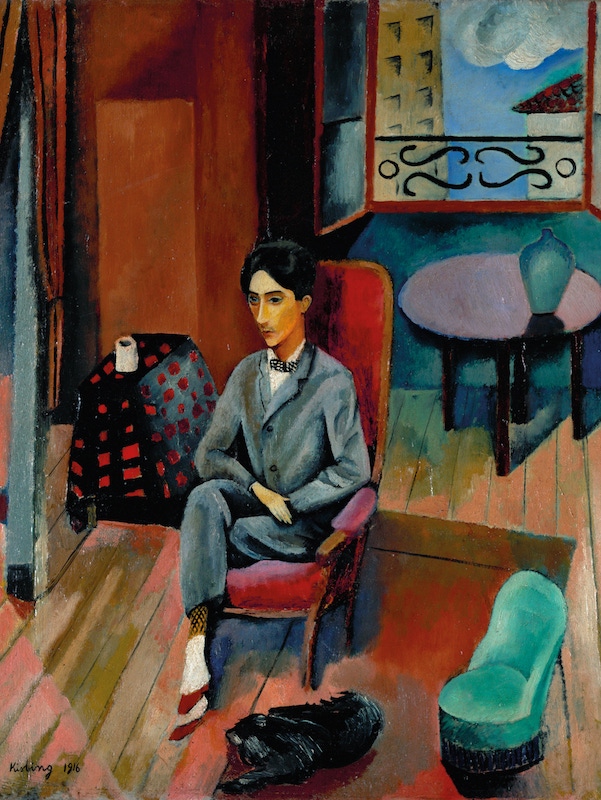

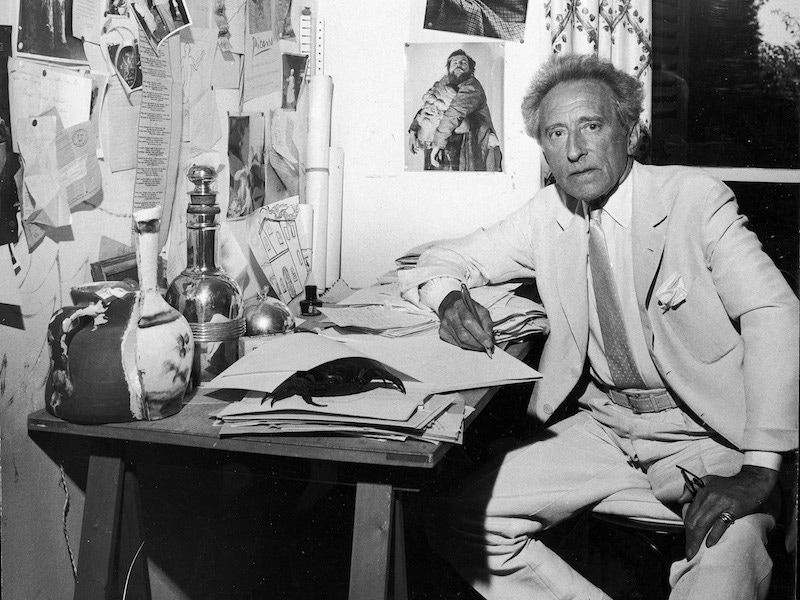

"Style is a simple way of saying complicated things,” wrote the film maker, poet, novelist, playwright, artist, designer, all-round dandy and aesthete Jean Cocteau, and one look at Irving Penn’s 1948 portrait of the man throws those words into sharp-tailored relief. Cocteau is perched on a chair, his beady glare boring disdainfully down on the viewer, his hawk-like profile accentuated by the drape of his beautifully cut jacket, artfully-casually draped over his shoulders and unfurling behind him like outspread wings. The crisp stripe of his tie is offset by a sharp sleeveless houndstooth pullover (Cocteau pioneered the sweater-beneath-suit look, and was an alchemist of creatively clashing pattern and texture). He hooks a thumb into the sweater while clasping a cigarette just-so in his tapering, bony fingers; his other hand rests on his hip, and the sinuous line is completed by a crossed leg flaunting one of the sharpest trouser creases ever captured on film.

This is the classic image of Cocteau — the Narcissus of Modernism and the movement’s first media darling; friend of Picasso’s, mucker of Man Ray’s, pal of Proust’s, disciple of Diaghilev’s, mentor of poets and actors like Raymond Radiguet and Jean Marais (the latter became his muse, starring in his best-known films, Orphée and La Belle et La Bête, as well as his lover), and idol/inspiration of future multimedia scenesters like Andy Warhol. A lapsed Catholic, he became the high priest of the avant-garde, officiating at Picasso’s wedding to ballerina Olga Khokhlova (he and the poet Guillaume Apollinaire held gold crowns over the heads of bride and groom; Picasso reciprocated by describing Cocteau as “the tail of my comet”), and taking up Diaghilev’s challenge to “surprise me” by writing the ballet Parade in 1917 (stage and costume designs by Picasso, music by Erik Satie), which garnered a gratifyingly emphatic first-night response: “The audience hissed and heaved,” Cocteau reported gleefully. “The women wanted to gouge our eyes out with hairpins.” Cocteau’s facility in a variety of mediums, allied to a love of mischief, left him pegged as a dilettante in the loftier boho circles of his day; he became known as the “Prince of Frivolity” after the title of a volume of poems he published at 21, but the fact that this epithet was usually prefixed by the word ‘boutonnièred’ is proof that, whatever his perceived artistic shortcomings, his sense of style remained unimpeachable.

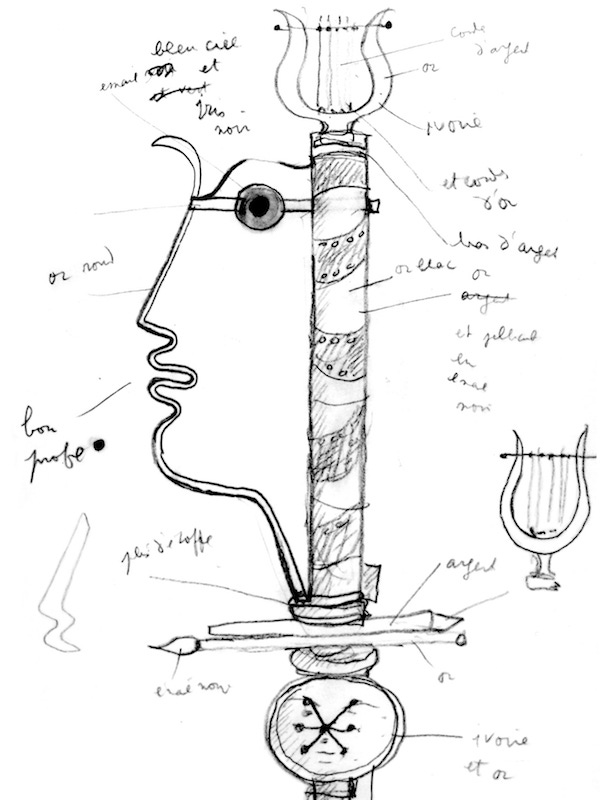

"Cocteau’s facility in a variety of mediums, allied to a love of mischief, left him pegged as a dilettante."What’s more, Cocteau’s gift for self-dramatisation and dogged pursuit of the modern attracted a coterie of like minds, from Modigliani to André Gide to Coco Chanel (who designed the costumes for his 1922 adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone). He promoted the work of the Surrealists, while denying he was one himself (like Groucho Marx, Cocteau rebuffed membership of any club that would have had the temerity to claim him). His recreational habits were also prescient; he became addicted to opium in the late ’20s following the death of his protégé Radiguet from typhoid fever, and many of his major works — the novel Les Enfants Terribles (1929), the film Le Sang d’un Poète (1930) — were written amid binges or furloughs. The latter film — part Surrealist primer, part anticipator of the French New Wave cinema of the ’60s — introduced what became Cocteau’s signature cinematic trope; an artist, in this case a poet played by Enrique Rivero, crashing through the surface of a large mirror, a door into the world of pure imagination, and a kind of narcissistic apotheosis. During World War II, Cocteau had the honour of being branded “decadent” by the collaborationist Vichy regime; riots attended performance of his plays, which were pre-emptively halted by the German police. He and Jean Marais then became post-war Paris’ pre-eminent high-art couple, cutting a swathe through Charvet (as they selected shirt fabrics) and the Rive Gauche (as they attended premieres of their film collaborations and perennial art-house stables, including 1950’s Orphée). In 1949, Cocteau was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, and embarked on speaking tours of the United States and the Middle East, regaling those style deserts with his singular brand of wasp-waisted insouciance. Ill health forced him into semi-retirement in the mid-1950s, but he still had a few tricks up his elegant sleeves, becoming one of the first men to (openly) undergo a facelift, and sporting matador-cape-and-leather-trouser combinations that anticipated Alexander McQueen’s more outré creations by at least half a century. In 1960, Cocteau appeared as himself in his final film, Le testament d’Orphée. He was now the grand old man of the avant-garde, and, if his trouser cuffs were as snappy as ever, he was becoming preoccupied with death, long his favourite theme: “As I grow shorter, she grows longer, she takes up more room, she worries about little details.” In the event, he died in suitably polished fashion a couple of years later. He was preparing a radio broadcast honouring his ailing friend Édith Piaf; when he heard that she had died, he exclaimed: “Ah, le Piaf est morte, je peux mourir,” and suffered a heart attack. He is buried beneath the floor of the Chapelle Saint-Blaise-des-Simples in Milly-la-Forêt, just outside Paris; the epitaph on his stone reads “Je reste avec vous” — “I stay among you.” For anyone who takes their dandyism dead seriously, those words are Le Testament de Cocteau.