Coat Of Paint: Jean-Michel Basquiat

Where do you begin when talking about the prodigious Jean-Michel Basquiat? His enigmatic mind — a mystery that should never be solved — and the nature of his work are topics of discussion that have remained newsworthy since his untimely death, aged 27, in 1988. He has been viewed as the greatest black artist ever, though such classification is crude and unhelpful. As he once made clear, “I am not a black artist, I am an artist”. I, for one, believe he supersedes that statement. His precipitous rise to stardom inevitably prefaced his sharp downfall. Basquiat’s story is not so much about the life of the world’s first commercially successful black artist, but of the struggles and tribulations that went hand-in-hand with fame in the 1980s New York art world. From a homeless, sui generis graffiti artist in New York in the late seventies, working underneath the moniker ‘SAMO’ with his friend Al Diaz, he quickly became one of the most recognisable and respected artists in the world. Basquiat broke away from the collaboration in 1979 (marked by his sign-off ‘SAMO is dead’) to pursue his solo career.

During the late 1970s, the art world was revitalised with the birth of neo-expressionism, a style of late-modernist painting and sculpture. Basquiat, in addition to other famous artists and contemporaries, such as Julian Schnabel (who in 1996 directed the biographical film Basquiat), Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz, was at the vanguard of the new movement. A necessary transition away from the movement’s minimalist, conceptual forebears and popular culture-ridden art planted the seed of its growth. Drawing upon cultural, social, political and mythical themes, delivered with the conveying tool of brash brushstrokes, neo-expressionism yielded a wealth of art that was rife with colour and vibrancy. At its forefront was the young, fame-hungry and confused Basquiat, uncertain of his role in the world, yet somehow aware of his immense talent.

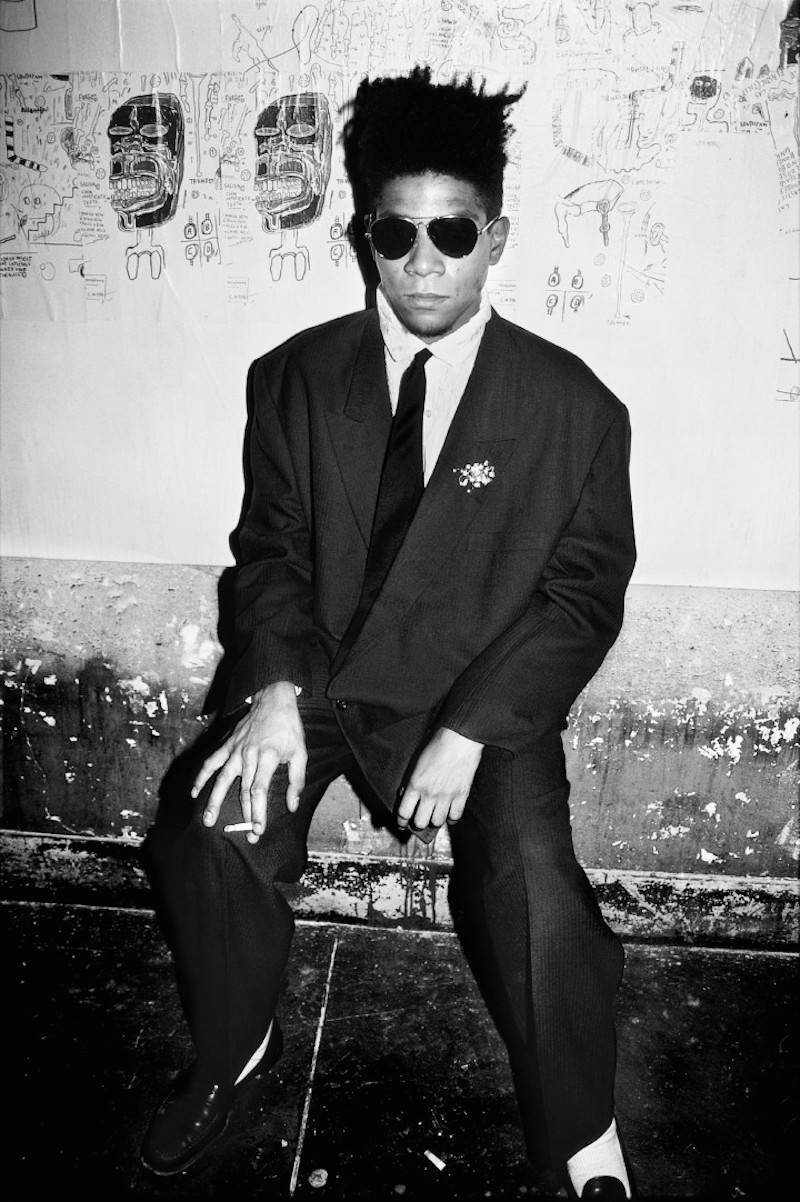

In the mid 1980s, the bifurcated role of art as raw commodity and vehicle for stardom reached its zenith. Even so, when in February 1985 Basquiat appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine, he made art history. He was by this point a world-famous artist, and yet landing the cover of New York’s most respected title underlined his status, an unprecedented feat for an African American artist at the time. Seated in a red armchair and holding a distant stare into the camera that reflects what one imagines was an empty, confused and anguished soul, he rejects the notion of socks and shoes. It’s as if he knows a secret that no one else is aware of. Is it a mark of his genius or a sign of his melancholy? With paintbrush gripped in hand, almost poised and ready to strike, he wears a relaxed dark charcoal pinstripe suit by Giorgio Armani, a favourite brand of his (along with Comme des Garçons, for whom he walked in their spring/summer 1987 collection).

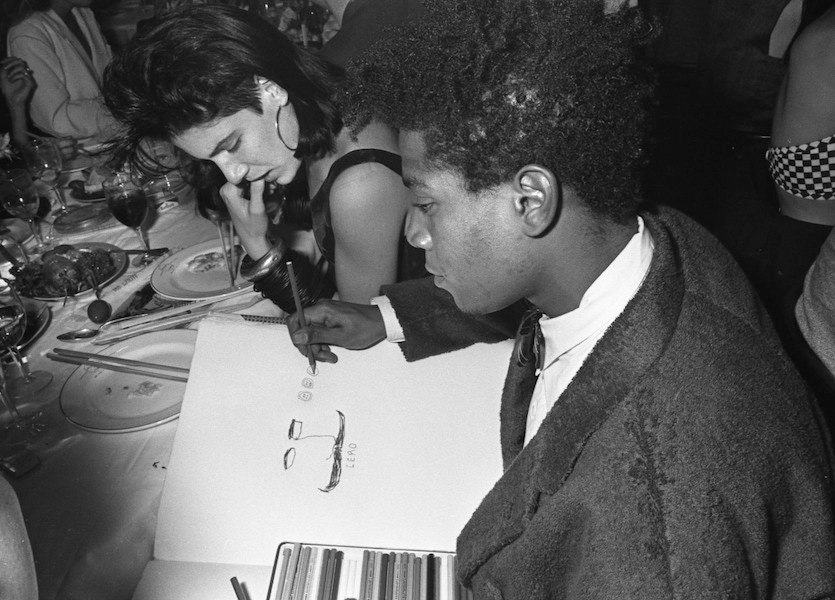

Basquiat’s sense of style is still somewhat revered in the fashion and art worlds. It’s nonchalant and louche, mixing high European fashion from Madison Avenue and low fashion thrift-shop finds from downtown — it’s a look almost more current today than it was in the eighties. It’s hard to know whether Basquiat would have given much daily thought to what he was going to wear, but once the money started coming in, Armani became his uniform, an armoured vehicle for self-expression in which he would paint all day and then disappear of an evening into New York’s buzzing club scene. He shunned the American sack style, which was simply not cool enough, while British suiting was considered far too stiff and impractical for the frantic artist who raced around his studio, working on one painting and then another. It’s no surprise, then, that he wore Armani, but it’s worth considering that New York in the 1980s was a melting pot of vastly contrasting fashions that defined eminently contrasting lifestyles: power sack-suits for the corporate Wall Street frequenters; adidas and streetwear staples that were uniform for the emerging hip-hop scene’s b-boys and b-girls; all-black clothing with studs and slashes for the surviving punks; and colourful extravagance for the fame-hungry wannabe artists in downtown Manhattan. It was a time of unapologetic individuality, long before the internet transmitted information and a homogenisation of style within seconds.

In some ways, there are clear personality parallels between Armani and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Both were crucial in breaking up the traditional constraints their industry had set upon them. Armani redefined how a man’s suit could appear, with his louche, unashamedly sexy look. As the lauded fashion writer Colin McDowell noted about Italian designers: “Turning their backs on the accepted line, Italian tailors set out to create clothes that not only looked young but, unlike the products of traditional tailoring, only looked good on the young […] this was a fresh concept in the staid and traditional world of gentlemen’s tailoring, and its effect was to bring youthful fashion into the mainstream.” Basquiat’s style of fashion was in the same vein as his artistic style. He referred to his work as “suggestive dichotomies”, a duality of self-expression. His work had central themes of wealth versus poverty and integration versus segregation, so by wearing expensive suits and painting in them (ruining them in the process), he was acting out yet another of these so-called “suggestive dichotomies”.

It would be interesting to know what readers of The Rake think about Basquiat and the suit. He was someone who had no real respect for a finely constructed garment, happy to wipe a colourful spectrum of paint from his hands on to the back of his thigh (while $100 notes lined his pockets). Was he being exploited or did he exploit the suit and its prerequisites? Equally interesting is how Basquiat was an African-American talent, silently screaming against the establishment and the racial restrictions it contained, using surfaces from canvas to rubber wheels, broken doors to football helmets in order to express himself. Yet Basquiat wore suits that had been designed by the hand of a white man. The lack of commercially successful African-American fashion designers in the 1970s and 1980s was symptomatic of societal prejudices.

During his short career, Basquiat’s vast canon of work constituted pieces created across a multitude of different surfaces and mediums. Following his death from an overdose (the autopsy cited an “acute mixed drug intoxication (opiates-cocaine)”, otherwise known as a speedball), Christie’s had the job of compiling the inventory of his belongings and the collection of work from his loft apartment on Great Jones Street in Manhattan. In addition to the 917 drawings present, they found 25 sketchbooks, 85 prints and 171 paintings, and a range of personal belongings: an Everlast punching bag, traditional African musical instruments, several bicycles, obscure antique toys, and a closet filled with Giorgio Armani suits — with and without a film of encrusted paint.