King of Bling: Farouk of Egypt

“I suppose that the greatest moment in the life of any revolutionary is when he walks through the royal palaces of the freshly deposed monarch and begins to finger his former master’s possessions,” wrote the freshly deposed King Farouk of Egypt in the early 1950s, adding that he would have liked to have been a fly on the wall when the pillaging took place: “I admit that I would have enjoyed seeing those prudish, clerkly sect leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood as they drifted through my rooms like elderly ladies on a cook’s tour, pulling open drawers, prying into cupboards and wardrobes, and gaping like country bumpkins at the number of the king’s clean shirts.”

Farouk was somewhat loose with the historical facts: he was overthrown by the Free Officers’ Movement of the Egyptian army, which staged a military coup that ignited the Egyptian revolution of 1952, rather than the Muslim Brotherhood. But he was spot-on about the shirts. During the 12 years of his reign as ‘King of Egypt and Sudan, Sovereign of Nubia, of Kordofan and of Darfur’, Farouk amassed more than a thousand bespoke suits, alongside museum-worthy collections of rare stamps and coins, cars (including a Mercedes-Benz 540K that Adolf Hitler gave him in 1938 as a wedding gift); jewels (he would shake a sistrum studded in diamonds, rubies and emeralds in order to summon his servants); watches and, allegedly, the world’s largest collection of pornography, including an “album of semi-nude photographs” found under his pillow. Farouk happily copped to the finery, but balked at the idea of smut. “They were classical artworks,” he protested.

So far, so kleptocratic business-as-usual, you might think: the usual tale of a detached leader who strip-mines his country of its wealth while leaving its people among the poorest in the world. It was a damning verdict that the aloof Farouk did little to challenge; indeed, the corruption seemed embodied in his bloated figure — the result of a fondness for industrial quantities of oysters and soda — and the cartoon-villain twists of his handlebar moustache (on whose oily lines David Suchet would later model that of his Hercule Poirot).

But modern historians argue that it’s not the whole story, pointing out that the Muhammad Ali dynasty, of which Farouk was the last significant scion, had worked wonders in lifting Egypt from a provincial backwater of the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 19th century into a state so strong that the Imperial British felt compelled to curtail its rise only decades later. “I can’t speak on the people’s behalf, but I think we did a titanic amount to change a country that was steeped in the Middle Ages,” said Prince Abbas Hilmi, modern descendant of the Ali dynasty, last year. “And many are looking back from the chaos and violence of our own era to a time of glamour, class, religious tolerance and a civilised society. Some even refer to it as ‘the beautiful era’.”

And Farouk was at its centre. At the time of his birth, in 1920, amid the precipitous decline of the Ottoman Empire post-World War I, Egypt was a British protectorate, nominally ruled by his father, Sultan Ahmed Fuad. Constant uprisings led the weary British to declare Egypt an independent state in 1922, and the sultan immediately declared himself King Fuad I, bringing him parity with other emerging monarchies in Hejaz (present-day Saudi Arabia), Iraq and Syria. Fuad had little love for his subjects: he was of Albanian descent, spent much of his upbringing in Italy (and resembled a dyspeptic Mussolini, with added Dali-esque moustache), and spoke no Arabic, describing Arabs as “ces cretins” for good measure. After divorcing his first wife, who’d failed to deliver the required heir, Fuad married 24-year-old Nazli Sabri, a free-spirited aristocrat with stark, silent-movie looks. When Farouk was born, eight months after the marriage, Fuad ordered ten thousand pounds in gold to be distributed to the poor, with a further eight hundred for Cairo’s mosques; Nazli, meanwhile, was confined to an Ottoman-style harem while producing Farouk’s four sisters (one of whom, Fawzia, would later marry Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran).

Farouk had a gilded-cage upbringing. The heir also lacked the astuteness or ruthless eye for political cunning that his father possessed, according to Khaled Fahmy, a history professor at the American University in Cairo. Where Fuad’s idea of a prank was to place a gold coin in a bucket of clear acid and watch, chortling, as unsuspecting servants screamed in flesh-seared agony when they tried to retrieve its contents, Farouk contented himself with more pedestrian hijinks, such as knocking the fezzes off the heads of court officials with well-aimed tomatoes and cucumbers after a copious palace lunch.

At 16 Farouk was sent for training at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich (along with a 20-man entourage), where he became known to the locals as ‘Prince Freddy’. While in London, Farouk was invited to lunch by King George V, where he met the future Edward VIII; the two took “an immense liking to each other”, according to Farouk (later, when they were both in exile, he would muse that “we have not yet met as two abdicated monarchs, but when we do I am sure that he will have a typically pungent comment”). As to character, the jury was firmly out. “In the notes of his English tutor in 1936, he was already lying a lot as a young man,” said Philip Mansel, historian and author of Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean. “He would lie about the number of ducks he bagged on a shoot. He was more interested in sleeping in and going on shopping trips to London than excelling himself academically.” It was somewhat of a rude awakening, therefore, when King Fuad died in April 1936 and the 16-year-old Farouk became Egypt’s ruler.

He began with a ringing panegyric — “I am prepared for all the sacrifices in the cause of my duty… My noble people, I am proud of you and your loyalty… We shall succeed and be happy,” he declared in a radio address to the nation — and spent the rest of his reign signally failing to live up to it, interfering with the parliamentary system, presiding over corruption scandals, allowing a small clique of landowners to snap up all of Egypt’s lush Nile-side farms, and indulging his taste for baroque Empire-style furniture to such a degree that the style came to be known as ‘Louis-Farouk’.

It wasn’t Farouk’s only extravagance. He forsook matters of state and family life (he’d married Safinaz Zulficar in 1938, a daughter of Egyptian nobility who bore him three daughters) in favour of racing his Rolls-Royces and Bentleys (they were always coloured red, so the police knew not to pull them over), and playing high-stakes card games.

During the hardships of World War II, Farouk attracted opprobrium for keeping the lights burning at his palace in Alexandria while the rest of the city was blacked out as a defence against Axis bombing. Due to the continuing British influence in Egypt, many Egyptians, Farouk included, were positively disposed towards Germany and Italy — one reason, perhaps, that he didn’t deem it necessary to decline Hitler’s Mercedes — provoking the British to ‘persuade’ the King to replace his government with a more pliant one (nonetheless, Egypt remained officially neutral until the final year of the war). The humiliated Farouk sought solace in torrid evenings at the Hotel Auberge in Cairo. “He would arrive at closing time, because gambling was the most important thing,” according to Roger Owen.

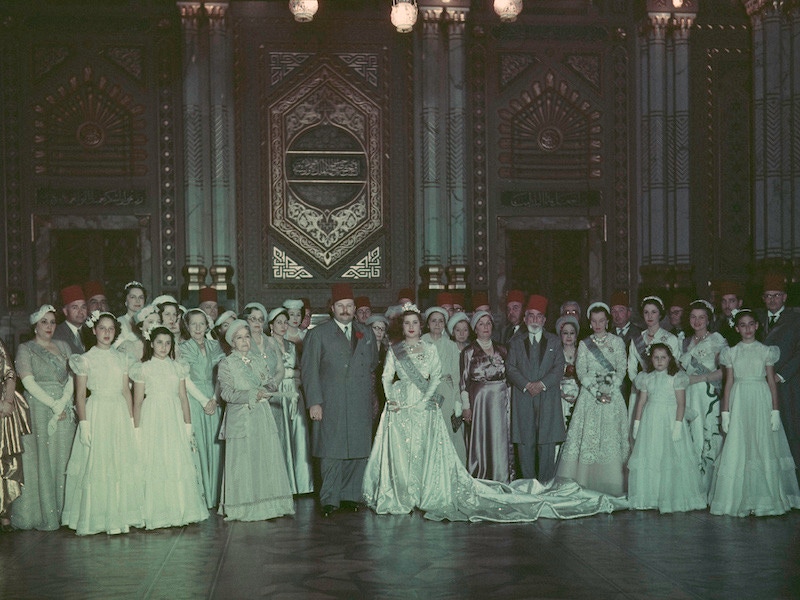

Farouk tried much to prop up his increasingly unpopular regime, not least a marriage reboot: he divorced Farida in 1938 and married Narriman Sadek, a 17-year-old known as the ‘Cinderella of the Nile’ for her middle-class background (though the 300-pound Farouk decreed that she could come to the ball only if she weighed 110 pounds or less on the wedding day). Among the gifts received was a jewelled vase from Haile Selassie and a writing set with Russian gemstone surround from Stalin; Sadek also bore Farouk his much-needed son and heir. None of it could save the king’s bacon, however, particularly after the Egyptian army’s failure to prevent the loss of vast chunks of Palestine to the state of Israel in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war (and accusations that his personal greed resulted in the army’s being outfitted with shoddy, antiquated weaponry). Farouk abdicated in favour of his infant son, and went into exile in Italy and Monaco, leaving his silk suits to the not-so-tender ministrations of that same army; Egypt became a republic in 1953.

Farouk was not unaware of his precarious status; he once quipped that soon there would be only five kings left: the king of England, and the kings of hearts, diamonds, spades and clubs. He now threw himself into closer acquaintance with the latter, haunting the resorts and rivieras of Europe while the Egyptian state sold off his coins and watches and displayed his jewellery collection in museums. Sadek, tired of Farouk’s philandering, divorced him and returned to Egypt. Farouk himself died after entertaining a young woman to a typically heavy supper at the Ile de France restaurant in Rome. “At his death, hospital officials found on his person the dark sunglasses he seldom abandoned, a pistol, two gold cufflinks, a gold wedding ring, a gold wristwatch, and $155,” as The New York Times itemised in its 1965 obituary. There may not have been any would-be marauders to gape, country-bumpkin-like, at this impressive array, but the paper’s readers could be in no doubt that, even in his diminished state, Farouk remained the eternal king of bling.

Originally published in Issue 56 of The Rake. Subscribe here for more.