Life was shit. everybody was horrible. but wasn't he wonderful!

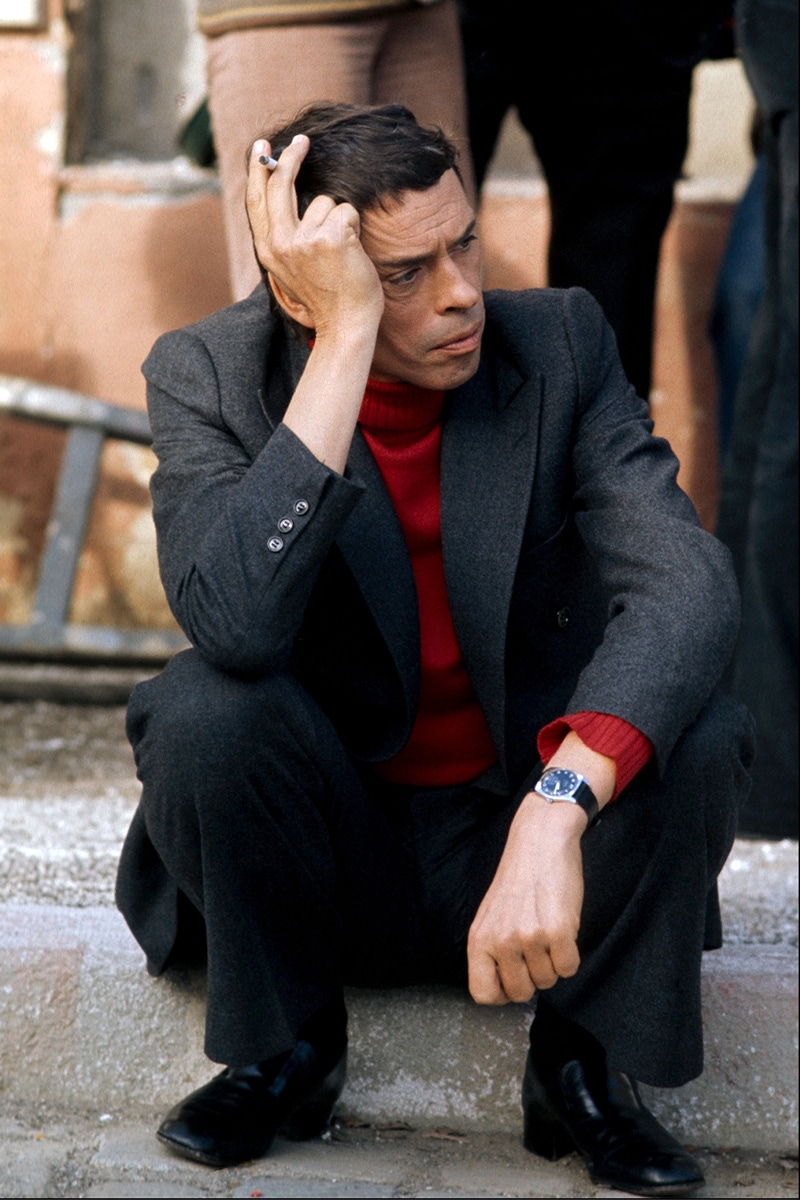

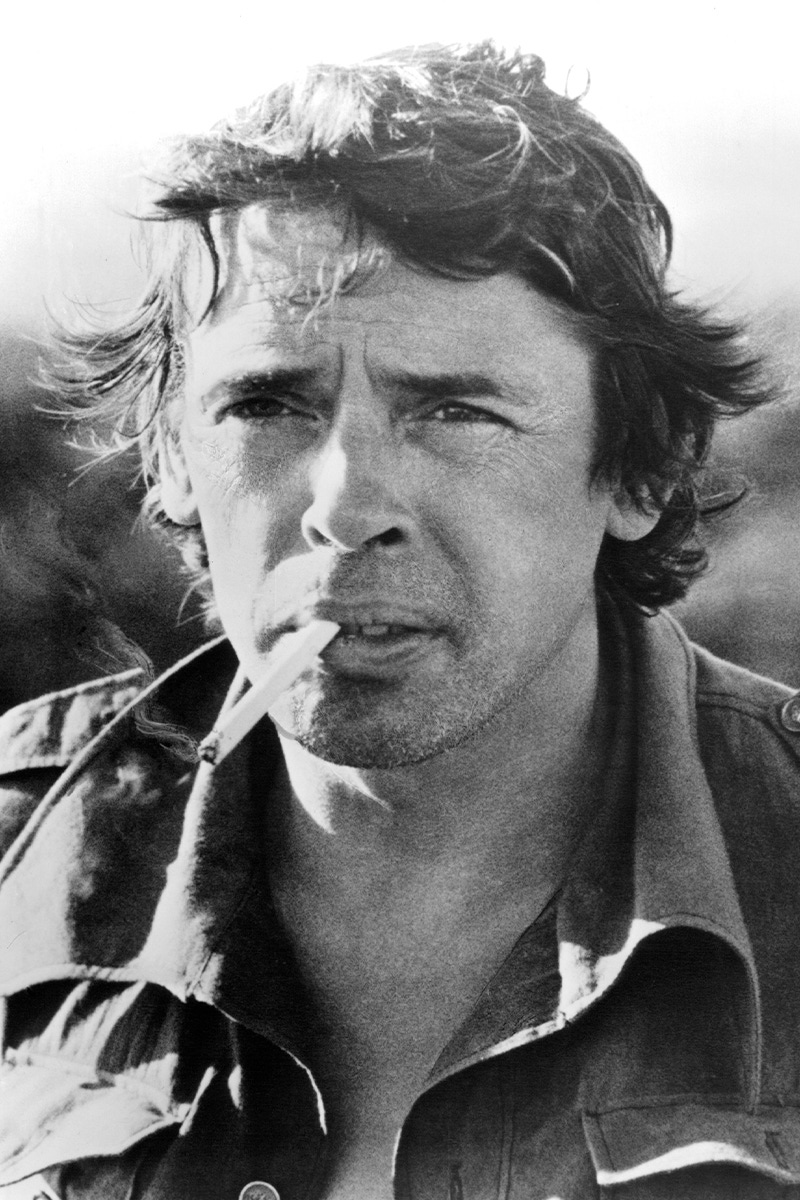

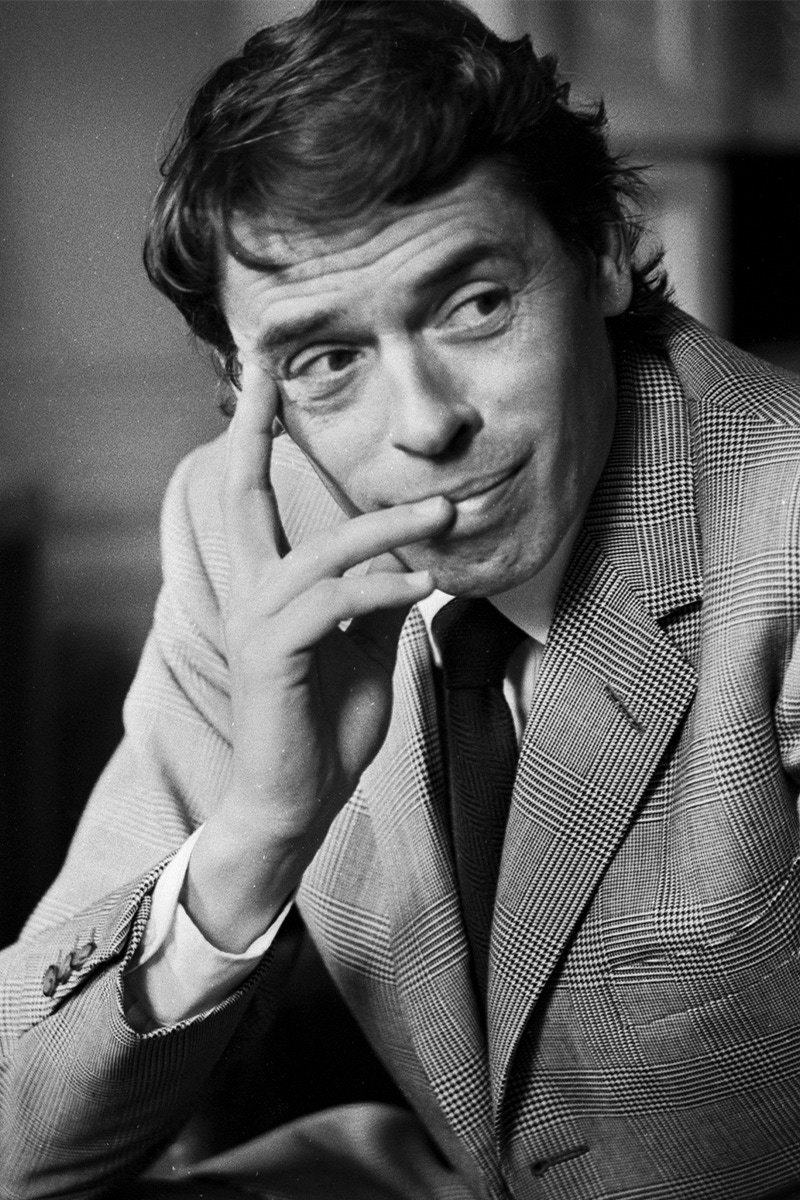

Jacques Brel sang of sex, death and bruised romance with the kind of mordant humour that’s to die for. ‘It is the intensity of life,’ the Belgian chanson decided, ‘not the duration.’

The YouTube clip is a bit grainy, and the sound quality a little fuzzy, but it leaves an indelible impression. Jacques Brel takes to the stage of Flanders’ Casino de Knokke, in 1963, to perform his breakthrough hit Quand on N’a Que l’Amour (‘If We Only Have Love’). He starts by strumming a guitar, looking rapt as he sings of love’s exhilaration (“Pour qu’eclatent de joie/ Chaque heure et chaque jour”), but the fervour builds over two and a half minutes to a defiant and explosive climax in which Brel’s gritty, breathless, anxious voice is pitching love against war in a kind of mortal combat (“Quand on n’a que l’amour/Pour parler aux canons/Et rien qu’une chanson/Pour convaincre un tambour”). As he relinquishes his instrument, a torrent of sweat is pouring down his face.

Amsterdam is a sordid tale of sailors drinking to the health of the whores who haunt the eponymous port (Brel said he wanted to create “a sea shanty which resembled a Breughel painting”); Au Suivant (‘Next’) tells of a 20-year- old grunt losing his virginity at a portable brothel that’s wheeled into his barracks (“I swear on the wet head of my first case of gonorrhoea!”); Les Flamandes pours scorn on his Flemish brethren (“We have been conquered by everyone, we are nothing,” he said, for good measure, in a later interview). Brel’s most famous song, Ne Me Quitte Pas, is a plaintive, raw-nerve plea to be spared imminent desertion by his objet de désir.

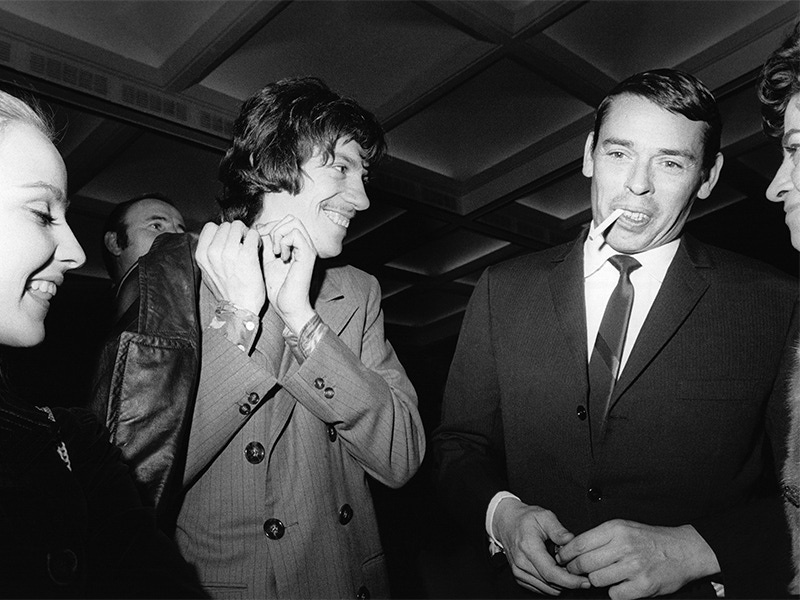

Such intensities, far from making the Brussels-born Brel a footnote in the ‘Name 10 Famous Belgians’ parlour game, established him as a kind of deity of chanson in France, a country keen to claim him for its own, and where he still sells more than 200,000 albums a year — significantly more than Edith Piaf. He also influenced a generation of artists who were burnt by his inflammatory torch songs, from Scott Walker and David Bowie (who both recorded Brel covers, including Amsterdam and La Mort) to Leonard Cohen, Jarvis Cocker and Tom Waits. “His magnetism breaks down the language barrier,” says Marc Almond, a superfan who once released an entire album of Brel covers.

His father owned a cardboard factory, and Brel was press- ganged in as the heir apparent in the late 1940s, but it wasn’t a great fit for someone who’d already steeped himself in the works of Verlaine, Hugo, Saint-Exupéry, Camus, and the nascent Existentialists (he preferred to play football with the workers rather than give them orders). He had begun writing songs with Franche Cordée (FC), a Catholic youth group that staged charitable shows in orphanages and hospitals, and his first gigs were at Brussels beer halls such as À la Mort Subite (Sudden Death), which still stands today. He married Therese ‘Miche’ Michielsen, a fellow member of FC, in 1950, and the couple soon found themselves with three daughters, but in 1953 the restless Brel sent a demo recording to Jacques Canetti, the boss of Phillips in France, who’d midwifed the careers of Piaf, Boris Vian and Serge Gainsbourg, among others. Canetti saw potential in the songs but was unconvinced by Brel, with his tombstone teeth and ample lips, which, added to a combed-forward fringe and a stage uniform of a buttoned-up jacket, white shirt and dark tie, gave him the look of a perennially gawky schoolboy. ( Juliette Gréco, for one, begged to differ: “He had eyes like charcoal,”she recalled on first witnessing him at Les Trois Baudets in Pigalle. “He began to sing and I was bedazzled. He was like some kind of magician.”).

Read the full story on Jacques Brel in Issue 84 - available to purchase on TheRake.com and on newsstands worldwide now.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.