Lord of the Dance

When ballet prodigy Rudolf Nureyev made a snap decision to defect from his native Soviet Russia, his already rarefied existence became a roller coaster ride of high-kicking, hissy-fitting and rampant bed-hopping.

Given his professional reputation, it was not the most elegant of moments, nor the most graceful way to break into the global consciousness. It is June 1961, and a 23-year-old ballet dancer is preparing to board a flight back to the USSR from Paris. Suddenly, he steps aside from his group and announces that he is not getting on the plane - he has decided to stay in France. His colleagues plead with him. He refuses.

A kerfuffle ensues with the group's Soviet handlers, and the young Rudolf Nureyev throws himself at airport security, exclaiming, 'Protect me!' His KGB handlers try to wrestle him back into line. 'Don't touch him - we are in France,' counters a coolly diplomatic French official. Nureyev is taken into custody, where he asks for political asylum, and so, makes what the ensuing media frenzy dubs his 'leap to freedom'. The rest of the group fly home. He must now make a new one for himself.

Had that unsightly scene in an otherwise humdrum departures lounge not occurred, Nureyev would perhaps not have become the superstar he did, feted as much for his movie-star charisma and Mount Rushmore bones (though, as the ill-advised attempt to actually play Rudolph Valentino in one biopic suggested, not for his acting) as his ability to dance.

Yes, within the ballet world, he would have been admired as a major talent - he had been made one of the Kirov Opera Ballet's featured soloists in 1958, when he had only just turned 20. And, certainly, the prodigy's defection was a serious blow to the company, not to mention Soviet propaganda - Nureyev being one of the first major cultural figures to flee the USSR (the following year, the Soviet authorities considered a covert operation to break one or both of his legs). But ballet is, to put it kindly, a minority interest - few of its stars escaped that elite arty bubble's gravitational pull, even fewer than before global mass media. Who knows if his worldwide celebrity would have followed if that moment at Paris-Le Bourget Airport hadn't occurred?

In 1998, secret KGB documents were temporarily declassified and revealed that, although the dancer's discontent was known to the authorities - the Kirov's artistic directors and the Soviet Embassy in Paris had actually ignored two KGB directives to return Nureyev to the Motherland 13 days before the scheduled departure - he actually had no plans to defect. Remarkably, given what he would be leaving behind, not least his family, he made the decision on the spot.

There was a certain amount of luck involved, too: the French border control chief Nureyev was first taken to following his cries for help was one Gregory Alexinsky, who happened to be a White Russian hostile to the Soviet regime. In Nureyev, however, he would not find a political ally: Nureyev had been motivated to escape to the West, less out of any distaste for the Soviet system than by a desire to dance. Perhaps that distaste grew: the Soviets did not permit him to see his mother again until she was on her deathbed, and even then, only thanks to the intervention of the French President. Later in life, he would spend a great deal of time hiding away in an underground mausoleum he had built, one covered in tiles that spelled out his mother's name.

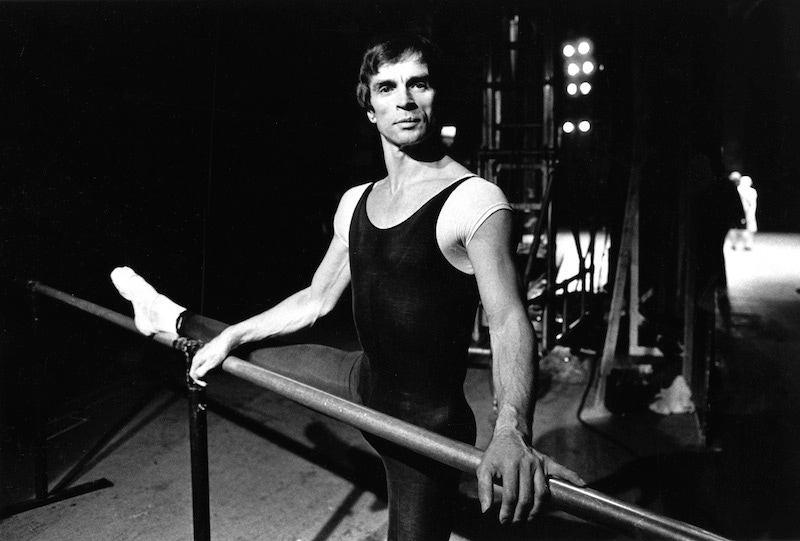

Certainly, Nureyev did dance - for the next 30 years, until his death from AIDS in 1993. This took him well into his 40s, long after most ballet dancers would retire, by which point he was dancing with spurred ankles and chronic back pain, sustained from years of lifting 'heavy' ballerinas. It was a long career, and one that allowed Nureyev to give a new public face to ballet in the West - to take dance to the people - not seen since his frequent partner Margot Fonteyn. This was all the more unusual given that he was a man in a world where, for generations, it was the women who had traditionally been feted.

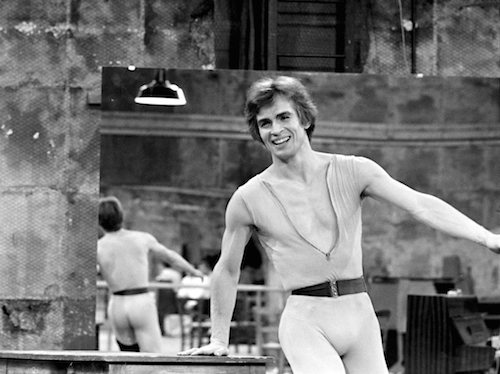

Indeed, his dancing heyday being the 1960s, his sinuous ease of movement became a pop-cultural phenomenon. The mop-top hair saw him dubbed the 'fifth Beatle', while his snake-hipped, fat-free form was thought to have inspired Mick Jagger's own on-stage strutting. 'Rudimania' for this 'Brando of Ballet' quickly caught hold. He hung out with Andy Warhol, Richard Avedon (who shot him nude), Peter O'Toole and Marlene Dietrich (who referred to him as 'that boy'). And the queues for tickets grew ever longer. 'The only critic,' he noted, 'is a full house.'

Clearly he could dance in a way few men had before: Nureyev was born on a train, so the running joke was that he was born in motion. While he was not necessarily the best male soloist of his times - the likes of Mikhail Baryshnikov, Peter Martins and Fernando Bujones are often cited by experts as superior in various ways - he gave ballet a new energy, a new sexiness. His aerial leap, in particular, became legendary. He broke the barrier between classical and modern dance, and gave new twists to the ballet canon, Swan Lake and Romeo and Juliet included. 'Technique,' he once opined, 'is what you fall back on when you run out of inspiration.' Yet he was being his own harshest critic: he told one interviewer that out of his 250 performances that year, only three were good.

Adrenaline became his fix. He fired himself up to perform such feats with unusual tricks: coming on stage 15 minutes late; waiting for the audience to do a slow handclap before he'd even think about making an appearance; sitting naked in his dressing room up to the minute he is called, and then asking whether they wanted him to go on stage like that. 'Old Galoshes', as he would refer to himself, danced with The Royal Ballet in England and the American Ballet Theatre, working with every major choreographer - from Frederick Ashton to Kenneth MacMillan, Martha Graham to Merce Cunningham and many more - and in time became as much in demand as a choreographer as a dancer, taking over as Director of the Paris Opera Ballet, the oldest ballet company in the world, in 1983.

He was, however, by many accounts, not a hugely attractive personality. As the choreographer Jerome Robbins put it: 'Rudi is an artist, an animal and a cunt.' He would let ballerinas he didn't like drop to the ground. He would rip up costumes during hissy fits. He was physically violent. While a guest at director Franco Zeffirelli's villa, Nureyev became upset by something, threw a chair at his host, smashed pottery with a curtain pole he'd torn down and, when thrown out, paused to lay a stool on the doorstep. François Truffaut called Nureyev a 'man-animal'. Perhaps he was right - Nureyev, after all, once claimed he was descended from wolves.

Despite all this - or perhaps because of it - he was, it seems, as much a success in the sack as he was in the theatre. Prolifically sexual, he was homosexual at a time when the gay liberation of the 1970s was in full force, but also took the occasional female lover. Later in life, he could recall just three, although Fonteyn - literally old enough to be his mother - was suggested by some to be one of Nureyev's lovers, while another was said to be Jackie Kennedy. One tell-all tale has him sitting in JFK's rocking chair and announcing to the First Lady, 'Unlike your husband, I have a powerful back.' Rumour also has it that he counted Bobby Kennedy as a conquest too. Jackie distanced herself on seeing that Nureyev had new eyes - for her son.

'I am the sexiest man alive,' Nureyev once modestly pronounced. 'Everyone who has gone to bed with me has fallen in love with me.' Even Miss Piggy: his appearance on The Muppet Show in 1978, preparing to dance 'Swine Lake', saw the porcine diva melting while he sat in a steam bath in just a towel. Certainly, he put it about wherever he could: even as a teenager, when he was sent to begin his training with Alexander Pushkin and his dancer wife Xenia, he was rumoured to have had affairs with both of them. Nureyev seemed to embrace sex, and his own neuroses, as much as he did dance: as an expression of vitality, as the necessary spark for his movement. And, indeed, a vitality whose passing - as evidenced by his own fading beauty - was said to concern him deeply.

'Rudolf told me there were going to be lots of boys around,' as Robert Tracy, fellow ballet dancer and Nureyev's lover for more than two years, once put it. The Danish dancer and mentor Erik Bruhn was also one of Nureyev's lovers. 'There were lots in my life, too... That was just the gay sensibility. He was content not to commit himself to one person.'

His life in the West brought him the artistic fulfilment he sought. It also brought a lifestyle of excess he would not have gotten to enjoy on the other side of the Iron Curtain: an apartment above Lauren Bacall's opposite Central Park; the Virginia ranch house where a room was devoted to an organ so Nureyev could play Bach, and to which friends and dinner would be flown in from New York; the house beside a nudist beach at St. Barts in the Caribbean; three islands on the Amalfi Coast; art, antiques and - a peculiar predilection - countless Turkish kilims. 'But,' he pointed out, 'everything I have, the legs have danced for.'

When he died, without a will, he left some £20 millon to a foundation named after him, which paid out sizeable sums in instalments to lovers such as Robert Tracy, on the condition that they did not talk about their relationship. Some have suggested that Nureyev's insatiable consumption - in bed as much as in chichi shops - was a product of, as it were, too much freedom: overwhelmed by the possibilities of living in the West, he indulged every one.

Certainly, his defection also brought a heavy psychological price - there has been speculation that the loss of his own family brought, at least towards the end of his life, a manic desire to have his own children. He often claimed, incorrectly, to have impregnated a few of his female lovers. He tried to persuade a close friend of his, Charles Jude, to allow him to father a child by Jude's wife - an arrangement that would somehow involve the mixing of the two men's sperm. Then, he suggested that he adopt not only Jude's children, but also Jude and his wife, and that they all live together in Nureyev's château.

Perhaps one can say that his offspring was more in art than in flesh, and that his art was as much in how he lived - with himself as his own muse - as how he danced. One of his lifelong goals had been to study with Bruhn and to work with the choreographer George Balanchine. He succeeded in the former but failed in the latter. Nureyev once offered Balanchine two months of his time when it was more customary for him to offer other choreographers merely the occasional day. But Balanchine perhaps sensed that even this would not be enough to both master and mentor Nureyev. 'When you are tired of playing at being a prince,' Balanchine told him, 'come to me.' But Nureyev never did tire of that.