Patrick Swayze: The Miracle Dude

Patrick Swayze combined macho swagger and fluid elegance in a unique way, and his acting style — a kind of artless sincerity — helped turn movies such as Dirty Dancing and Point Break into pop-culture classics. Yet what remains of Swayze’s life and work is more significant still: an unfashionable sense of joy.

Not long ago, I found myself, through no fault of my own, at the stage version of Dirty Dancing. As expected, the auditorium was oestrogen-heavy, and as the rough-diamond dance teacher, Johnny Castle, got to grips with the artless Frances ‘Baby’ Houseman and helped her unleash her inner twerker, the women around me responded with shining eyes, flushed faces, and the occasional whooped exhortation (there may have been hen parties present). The deathless line “Nobody puts Baby in the corner!” was greeted with a tumultuous cheer, and the climactic mass singalong suggested that, yes, the punters had had the time of their lives, and they owed it all to… whom?

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” my companion said, towelling herself down in the lobby afterwards. “The guy playing Johnny was fine, but everyone in that audience had the image of Patrick Swayze in their mind’s eye.”

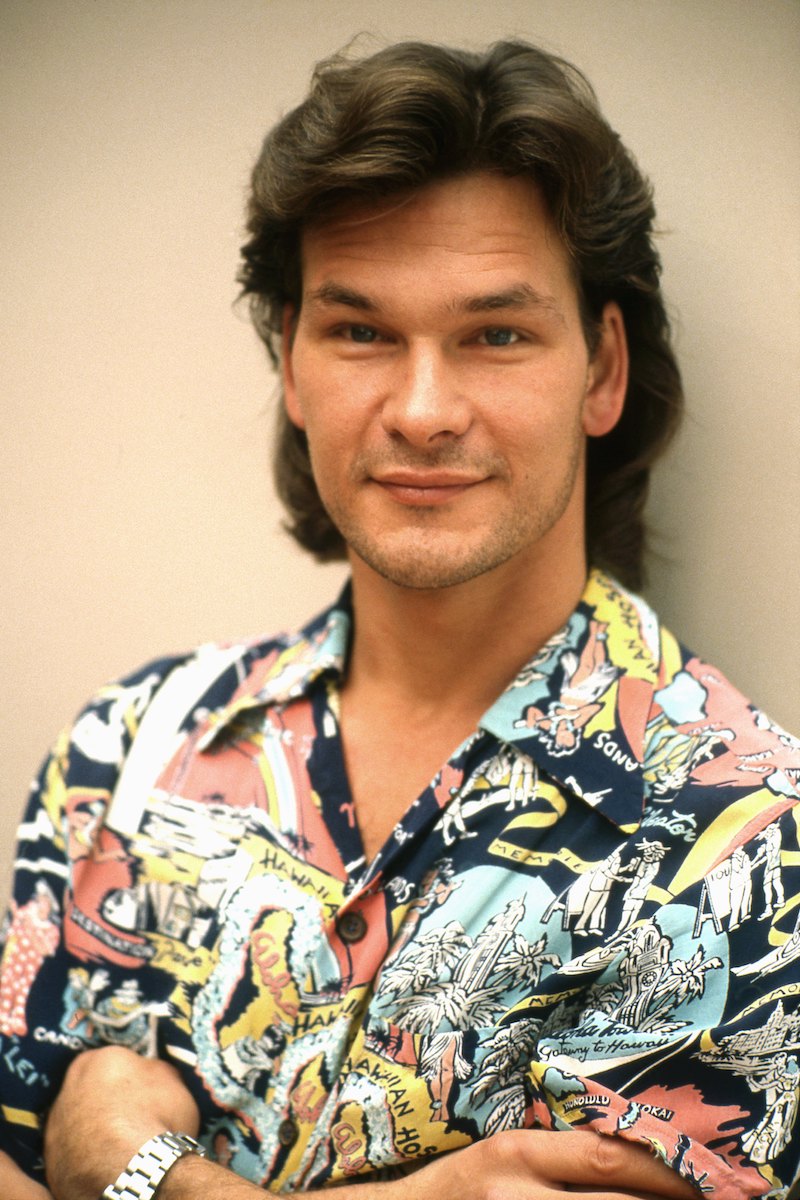

She was right, of course. The 1987 movie made Swayze’s name as an actor who brought a kind of loopy intensity to unpromising B-movie material, elevating it into pop-culture immortality, whether it was Dirty Dancing’s hackneyed coming-of-age story or the bonkers F.B.I.-rookie-infiltrates-surf-dude-bank-heist-gang set-up of 1991’s Point Break. It didn’t hurt that he’d studied at the Joffrey and Harkness ballet schools in New York before turning to acting, and exuded physical grace in all his roles, whether he was quick-stepping, brawling, or wave-riding. It also didn’t hurt that, with his tousled coif, sharp cheekbones, nutritious demeanour, and penchant for denim jackets with rolled-up sleeves, he could have been the fourth member of the wholesome Nordic pop trio A-ha. But it was his ability to deliver ironic T-shirt-ready lines like “Pain don’t hurt” (Road House, 1989) or “It’s not tragic to die doing what you love” (Point Break) completely deadpan, without a trace of self-consciousness or a knowing wink, that was really winning. While his peers got tangled up in Method madness or phoned in their performances, Swayze exuded a kind of artless sincerity with every take. And in an era when most actors who rose to the bedroom-poster level of fame played either to the girls (Rob Lowe, Michael J. Fox) or the guys (Arnie, Stallone, et al), Swayze’s appeal transcended gender. Women could fantasise about mambo-ing with him at the Sheldrake (and obviously still do), while men could imagine him as a clued-up, hard-knocked but Zenned-out big brother. “People don’t identify with victims,” he once said in an interview with the Associated Press. “They identify with people who have the world come down on their heads, and who fight to survive.”

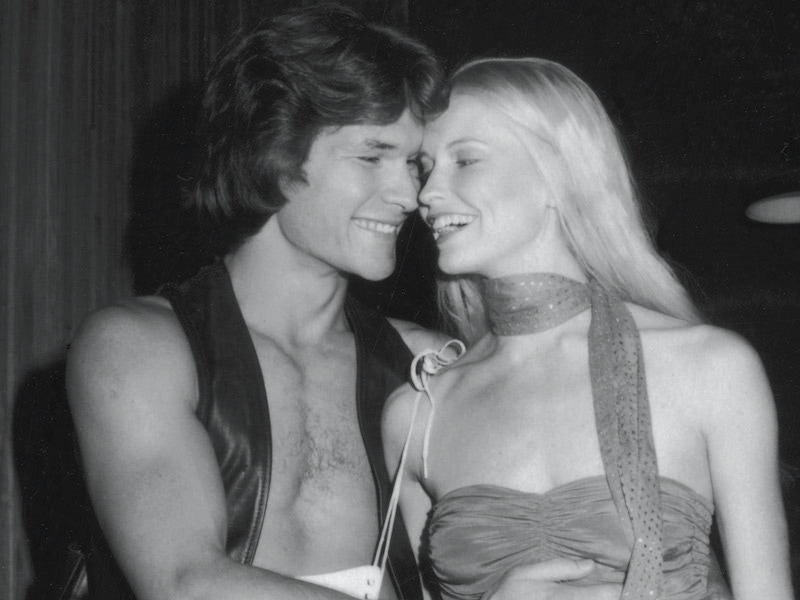

Spoken like a true obdurate Texan. Swayze was born in Houston in 1952; his father, Jesse, was an engineer and rodeo cowboy (his son would later buy a ranch in the San Gabriel Mountains, opining that, in contrast to the Hollywood schmooze, “your horses don’t lie to you”), while his mother, Patsy, was a dance instructor and choreographer. He began dancing as a child — “I kind of came out of the womb onstage,” he said later — for which he was mercilessly ribbed. “I was also a student athlete, until I got a football injury,” he said. “But dance was the thing for me. It taught me so much about movement, stillness, expressiveness, when to hold back and when to let go.” It also brought him a lifelong partner in Lisa Niemi, a fellow Houstonian. The pair met at his mother’s ballet school when she was 15 and he was 19, and they married in 1975.

Swayze eventually became a member of New York’s Eliot Feld ballet company, and made his Broadway debut in 1975, hoofing it up in Goodtime Charley, before being cast in the original Broadway version of Grease, eventually taking over the lead role of Danny Zuko. Hollywood producers noted his feline suppleness — and his way with a leather jacket — and he made his screen debut in 1979’s Skatetown, U.S.A., a roller-disco movie starring Scott Baio, in which Swayze played Ace Johnson, a local hood at the head of a fearsome Starlight Express-style posse. He could already see the potential pitfalls of typecasting, however. “It seemed like I could become a teenybopper star with not too much trouble,” he told Toronto’s Globe and Mail newspaper in 1984, “but I knew if I accepted that, it would take years to win credibility as a serious actor.”

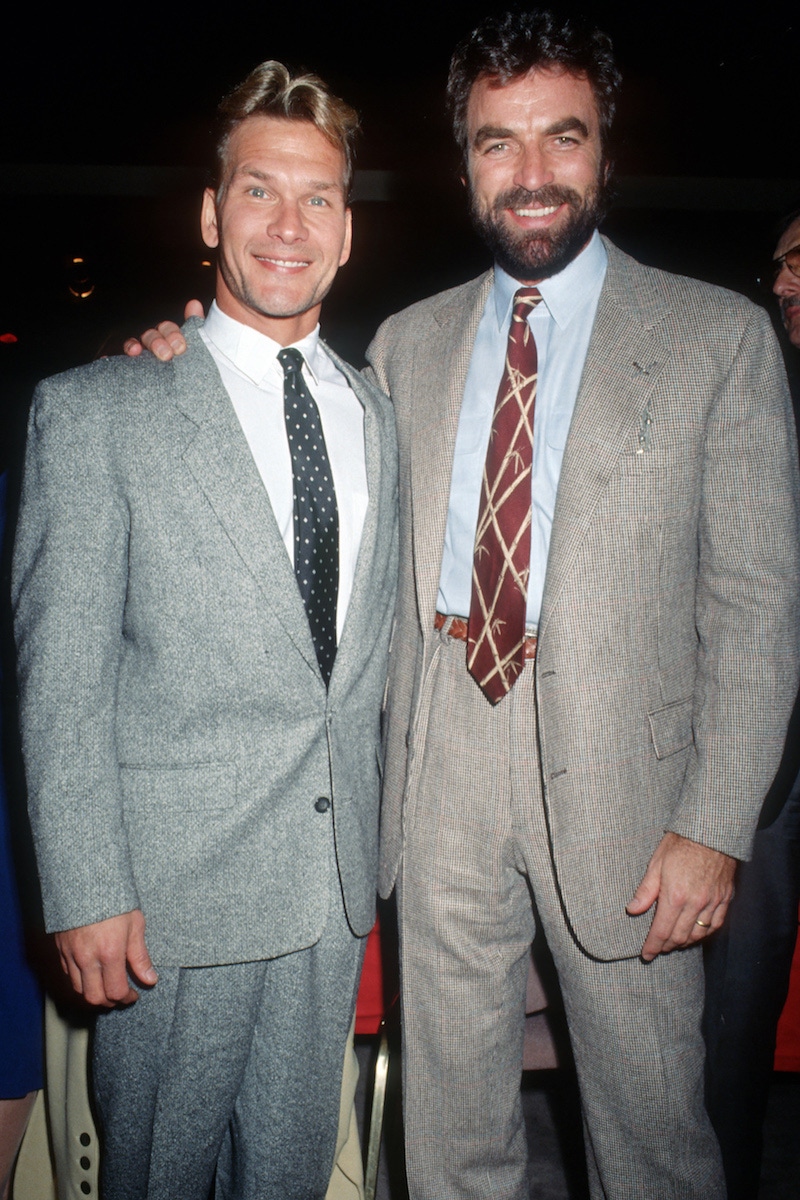

Instead, Swayze built a reputation as a character scrapper, taking on everyone from invading Russians to Union soldiers and rich kids in Madras shirts — always with a somewhat forbearing, this-hurts-me-more-than-it-hurts-you mien — in the early eighties likes of The Outsiders (alongside Tom Cruise and Matt Dillon), Red Dawn, and the T.V. mini-series North and South. But it was Dirty Dancing that proved he could be a lover and a fighter. “In the film, dance is not so subtly used as a metaphor for sex,” wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer’s movie critic Carrie Rickey, “and, yes, Swayze’s totally buff, but his dance training helps to establish a slow-burn physical rapport on the floor. Look at the attentiveness and focus, his hungry eyes fixed on Jennifer Grey’s, his concentration on her performance. It’s both powerfully romantic and deeply sexy. There’s a moment where he kind of leaps off the stage, and I heard a collective gasp from the audience in the movie theatre. It was like watching Baryshnikov crossed with James Dean.”

If Dirty Dancing put Swayze on the romantic-lead map, 1990’s Ghost sent him into the stratosphere. His character, an archetypal loft-living yuppie banker, is murdered early in the film and spends the rest of it as a spirit, desperately trying to communicate with his fiancée (Demi Moore). He seizes his chance, quite literally, when she’s seated at her potter’s wheel, spectrally spooning her as the gooey vessel beneath her trembling hands gets progressively wonkier and the Righteous Brothers’ Unchained Melody swells on the soundtrack. It’s a scene that doesn’t so much flirt with ludicrousness as get well beyond fourth base with it, and it gave birth to a thousand parodies, yet it works, thanks to Swayze’s emotional commitment. He was proud of Ghost, as he told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1990: “I needed to do something that affected the audience in a positive way, made them feel better about their lives and helped them appreciate what they have.”

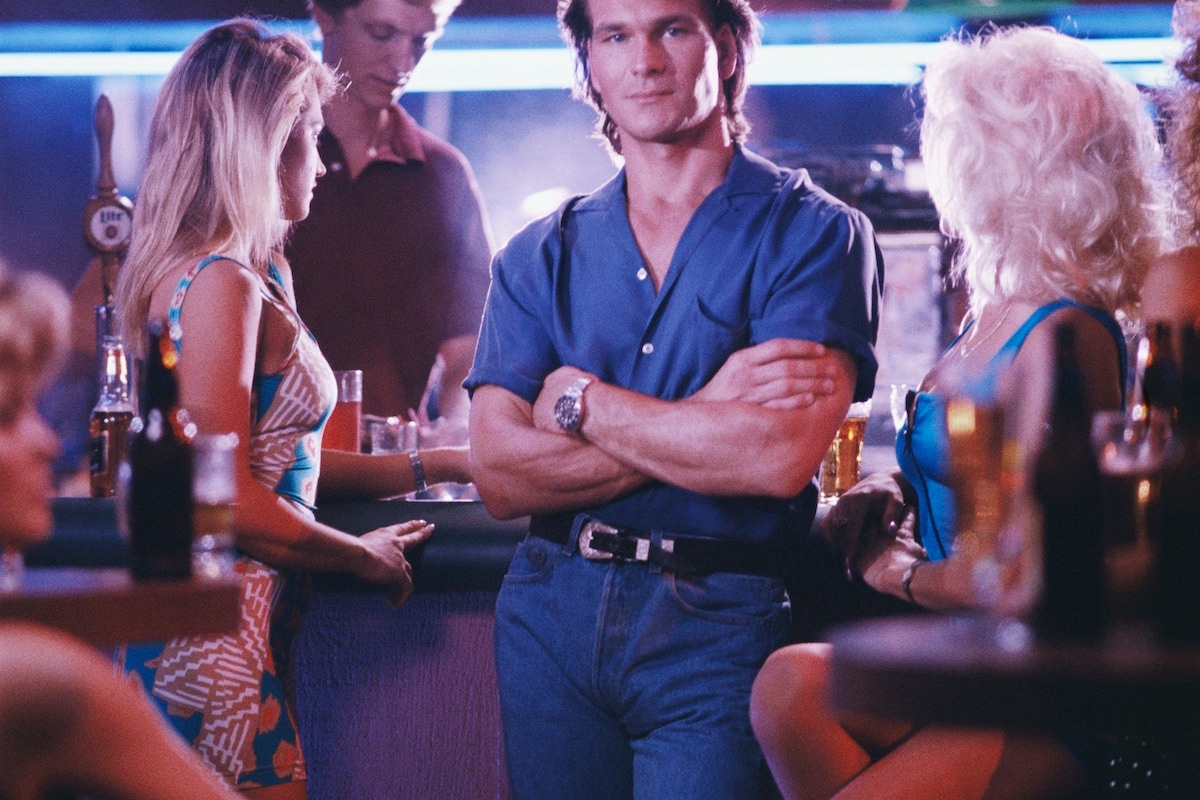

If you want the essence of Swayze, however — that combination of macho swagger and fluid elegance that seems to serve both as affirmation of unreconstructed masculinity and a critique of it — look to Road House and Point Break. In the former he plays John Dalton, a philosophy graduate turned nightclub bouncer who defends a bar in small-town Missouri from a band of local gangsters with a mixture of martial arts chops and Zen restraint, dishing out haikus along with joint locks. In the latter, his blonde-ringleted, skateboarding-surfing, Reagan-masked bank robber is named Bodhi (short for Bodhisattva; Swayze was a student of Buddhism in real life), and his spiritual equilibrium coexists unproblematically with a readiness to kick ass. The final scene, in which Bodhi, cornered by the F.B.I., chooses to submit to the ultimate, unsurfable wave rather than surrender to the law, showcases Swayze’s deranged grandeur at its dizziest height (and surely went on to inspire the whacked-out character of Hansel, the nemesis of Ben Stiller’s Zoolander).

Following Swayze’s imperial phase, he popped up in a series of disparate roles — a drag queen in To Wong Foo, a noble doctor in City of Joy, an obnoxious motivational speaker in Donnie Darko — all of which were testament to a restless spirit. “The only plan I have,” he told the Chicago Sun-Times in 1989, “is that every time people have me pegged, I’m going to come out of left field and do something unexpected.” But middlebrow roles in worthy projects didn’t suit his brand of blissed-out absurdity. “Critics rarely praised his acting ability,” noted The New York Times drily. “At best he was commended for his athletic presence and stalwart demeanour.”

There was a heroic amount of the latter on show after Swayze was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in January 2008. Six months later he’d outlived his prognosis and was filmed at an airport, smiling at photographers with that familiar air of preternatural calm, and calling himself “a miracle dude”. He even went through with plans to star in The Beast, a T.V. drama in which he played an undercover F.B.I. agent, filming a complete season while undergoing treatment. “How do you nurture a positive attitude when all the statistics say you’re a dead man?” he inquired in a New York Times interview. “You go to work.” By now his identification with his most indelible characters — those unruffled counterpunchers, who, if they’re going to go down, are going to go down gloriously — was virtually complete. He died in 2009, aged 57, but the surplus measure of joy he brought to his most preposterous roles has proved enduringly infectious. He’s forever purloining the mic and the stage to lead the last dance of the season, ready to transcend cliché and ascend to that higher plane.

This article originally appeared in Issue 63 of The Rake.