Picasso's Muses

In the wake of a new exhibition exploring Picasso's relationship with his muses, The Rake asks whether the greatest artist of the 20th century would have achieved such fame and fortune without the irresistible attraction of his women?

Lauded as the greatest artist of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso was born with exceptional talent, able to deftly work across in a multitude of mediums and artistic movements. His oeuvre remains unmatched in art history. But, when considering our July theme, Love and Marriage, Picasso, who lacked from the will to remain abstinent, couldn’t be a more apt subject.

Highlighting the man’s combined frivolities and artistic achievements, the Vancouver Art Gallery is currently hosting an exhibition titled Picasso: The Artist and His Muses, which is split into six sections and which examines how his work evolved in conjunction with his handful of muses.

The exhibition starts with Fernande Olivier; Picasso was young, poor and unknown, his groove at the time, the Rose Period, was a warm summery aesthetic with central themes of the jovial, jokers and jesters, or as the French say, saltimbanques.

Soon after meeting, they moved to southern Spain, where Picasso would adapt to the cultural and geographical nature of his surroundings — thus altering his artistic philosophy, which paired with Olivier’s influence, subsequently started one of the greatest artistic movements in modernity: Cubism. In 1909, he sculpted Head of a Woman, a cubist bust of Olivier. The movement shook the foundations of European modern art, elevating portraiture and sculpture to another dimension, and diluting the visual representations of the human form into an array geometrical shapes and patterns.

The exhibition then moves onto Picasso’s succeeding muse Olga Khokhlova, whom he moved back to Paris with after meeting her in Rome in 1917. His work became less experimental and visually vivid, partly due to the birth of his first child. Themes of motherhood became a frequent concern, as seen in the study Seated Nude (1922). However, his divergence from colourful expression and cubism to the neo-classical can also be explained by the Parisian cultural context of the time, with the wounds of World War I still very much raw.

Their relationship swiftly came to an end when Olga learnt of Picasso’s affair with Marie Thérése Walter, who Picasso started to see when she was only 17. The vibrancy of a young woman in his life was then reflected in his paintings, most notably in the Female Bather with Raised Arms (1929) and Femme Couchée Lisant (1939), which was heavily inspired by the then popular art movement, Surrealism.

In 1935 Picasso met Dora Maar, a talented surrealist photographer come poet. Maar and his then muse Walter encountered each other in Picasso’s studio, wrestling on the ground much to Picasso’s delight, which is one of his “choicest memories”.

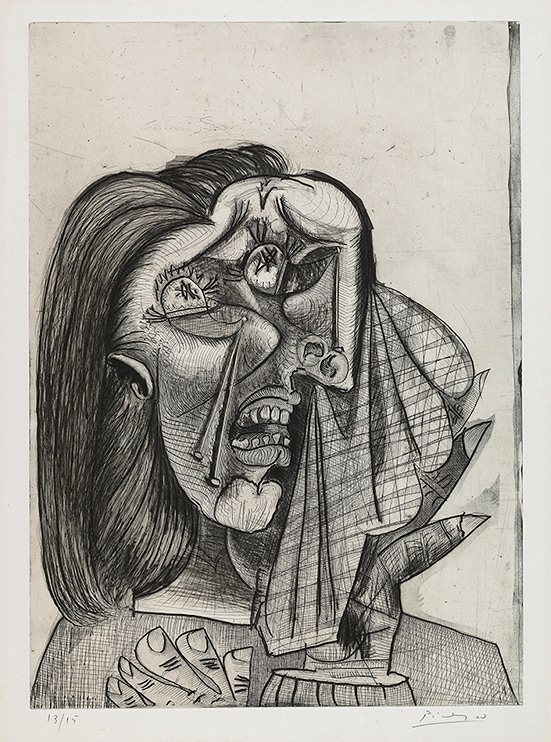

Leaving Walter for Maar laid considerable influence on his work and artistic outlet, evident through the composition of numerous works, most notably The Weeping Woman and Guernica (1937), (despite not being on show in Vancouver, Guernica an intrinsic work that should be noted, as it is one of the century’s most politically charged and emotive works of war art). Both were created against the backdrop of the atrocities of the Spanish Civil War — which had considerable effect on Picasso, striking a blow close to home, also apparent in his painting of Maar named Bust of a Woman (1943), with it’s sombre palettes and fractured planes. It can be argued that Picasso’s move away from colour was the result of the war; yet, a core component of this change is also undeniably due to his muse’s influence.

"It can be argued that Picasso’s move away from colour was the result of the war; yet, a core component of this change is also undeniably due to his muse’s influence."The transition out of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, plus a new relationship, swung Picasso out of his muted aesthetic and back into what he is renowned for — colour. Living in Paris, he met Francoise Gilot, an art student 40 years younger than him who turned the lights on in his creative outlook. They bore two children and can be seen in his panel paintings titled, Claude and Paloma and Femme Au Collier Jane (1946) which highlights his change in narrative and artistic approach, with vivid rays of purple, red and yellow. Yet the continuous theme of short-lived relationships remains present. In 1953 he met Jaqueline Roque, whom he later married and was with till the day of his death in in 1973. It was this relationship that was the most productive for Picasso. He produced over 400 works on her, more than any of his muses beforehand, continuously experimenting with colour and the female nude, as seen in his erotically charged Nu Assise Dans Un Fauteuil II (1963). Food for thought; would Picasso have achieved such fame and an unmatched canon of work, had he not enjoyed a flurry of stormy relationships with his muses and wives, or rakish escapades? Without the women in his life he could not have switched themes and experimented with various artistic formats. Geurnica may have looked vastly different without Maar’s influence and had he not met Olivier, he may not have discovered Cubism. His awe-inspiring legacy is intrinsically linked to the life that he shared with his muses, and the cynic might say, that we owe as much the influence of his muses as we do to the man’s own talents. Picasso: The Artists and His Muses is on at the Vancouver Art Gallery until October 2nd, 2016.