Pitch Perfect: George Best

Wasteful? To an extent. Self-destructive? Massively. Violent? Occasionally. But to call the life of George Best tragic is wide of the mark. His style, meanwhile, was as deft as his footwork...

No footballer has ever embodied the 'Beautiful Game' sobriquet quite like him. David Beckham looks like an Adonis, plies his craft with a balladeer's grace and dresses superbly, but has never been so potent a force on the field and speaks like a Cockney C-3PO. Wayne Rooney can be as devastatingly effective, but plays a rougher, boorish game - as well as looking like he was carved from a giant potato. Pelé and Diego Maradona outshone him - by a fraction - in footballing terms, but are no more style icons than Giorgio Armani is a midfield powerhouse.

George Best, though, was the full package. The man who had it all. And then lost it all. Or so certain commentators, especially those of a sententious nature, would have us believe. But is it fair to write off Northern Ireland's most revered export as nothing more than a fallen hero? Or is that not a little cursory, trite even, to dub his extraordinary life simply 'tragic'? In fact, is there - just maybe - a little dash of wry wisdom in his infamous toast to his own hedonism - 'I spent a lot of money on booze, birds and fast cars - the rest I just squandered'?

Best was just 15 when a Manchester United scout plucked him from the working-class streets of the Cregagh Estate in Belfast. He was just 59 when his booze-ravaged internal organs finally surrendered in London's Cromwell Hospital in 2005. His faults were manifold and manifest, but I would suggest that Best lived, loved, laughed and achieved more in those 44 years than his more puritanical critics could in a thousand dry, guilt- plagued lifetimes.

His playing career was short but sublime. There will never be consensus on which of the 178 goals he scored in 466 appearances for United, helping them win the First Division title in 1965 and 1967 then the European Cup in 1968, were the most mercurial. His darting runs were terrifying, his shot lethal, his interpretation of game-play uncanny. He was strong, innovative, tenacious. But it was his prodigious dribbling that made the hairs on the back of spectators' necks spring to attention. 'With feet as sensitive as a pickpocket's hands, his control of the ball under the most violent pressure was hypnotic,' as revered sports writer Hugh McIlvanney put it in his book, McIlvanney on Football.

Despite ending his career in lower-division clubs - in Britain, Spain, Australia and America - the only career regret Best could possibly have had the day he died would be never having had a stab at the World Cup. When he quit first-class football aged 27, it wasn't just to pursue women and wine. They came on a platter already. He did so simply because he wasn't enjoying it anymore. That, and the fact that some things, even in Britain, are bigger than football. Like a cultural revolution. And Best was at the hub of one.

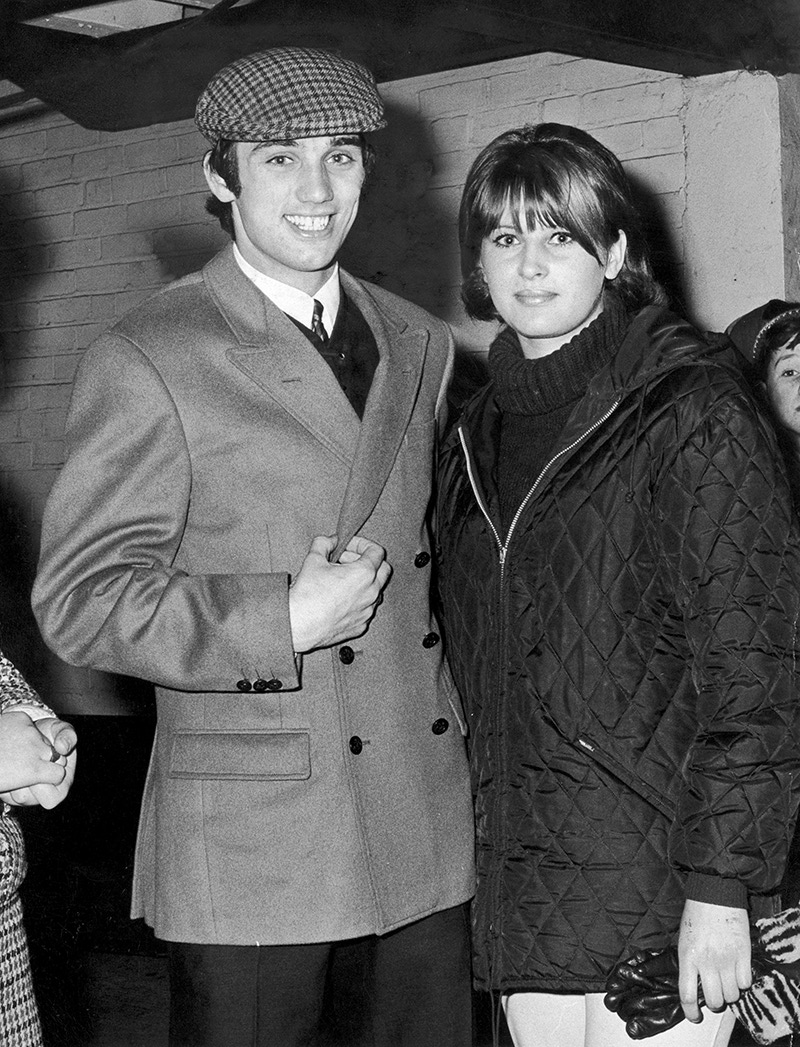

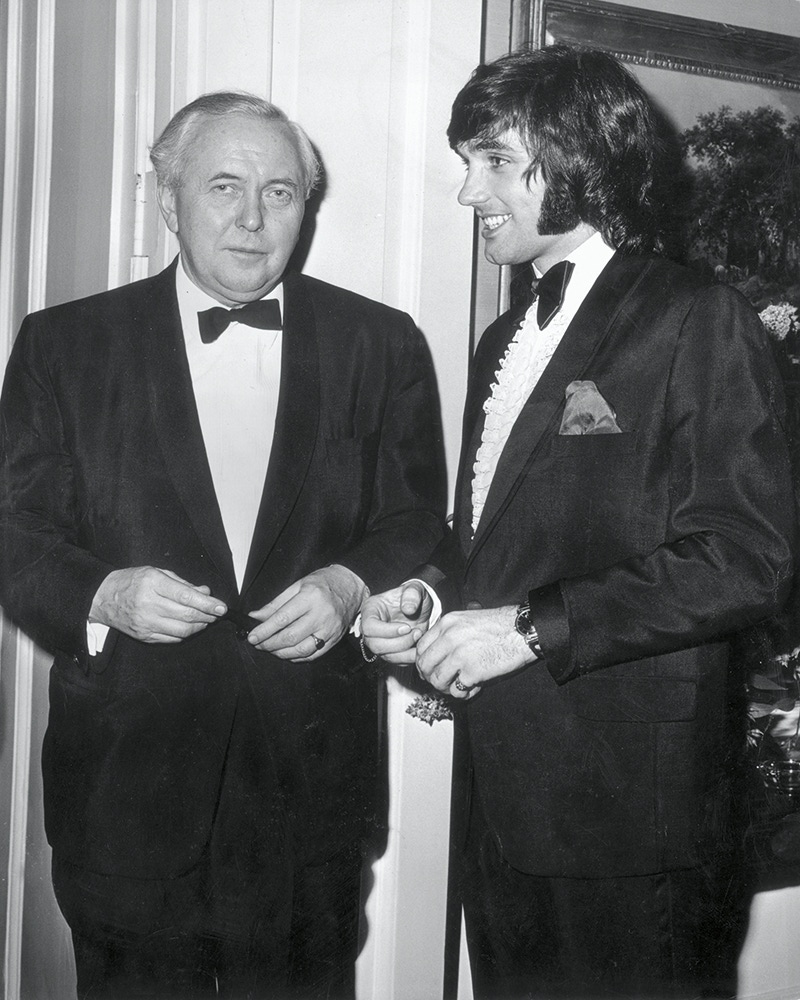

Always eager to flick ash in the eye of authority, Best was the first notable footballer to grow his hair long and spice up his wardrobe in the boutiques sprinkled around Carnaby Street and the King's Road. Some people even, only half-jokingly, refer to him - rather than legendary producer Sir George Martin - as the 'Fifth Beatle'. It was he, not Beckham, who was the first global football icon - and he got there without the winds of the mass media and man-brand peddlers in his sails. 'Beckham has total control of the planet,' as he once put it. 'I had an agent who lived in Huddersfield.'

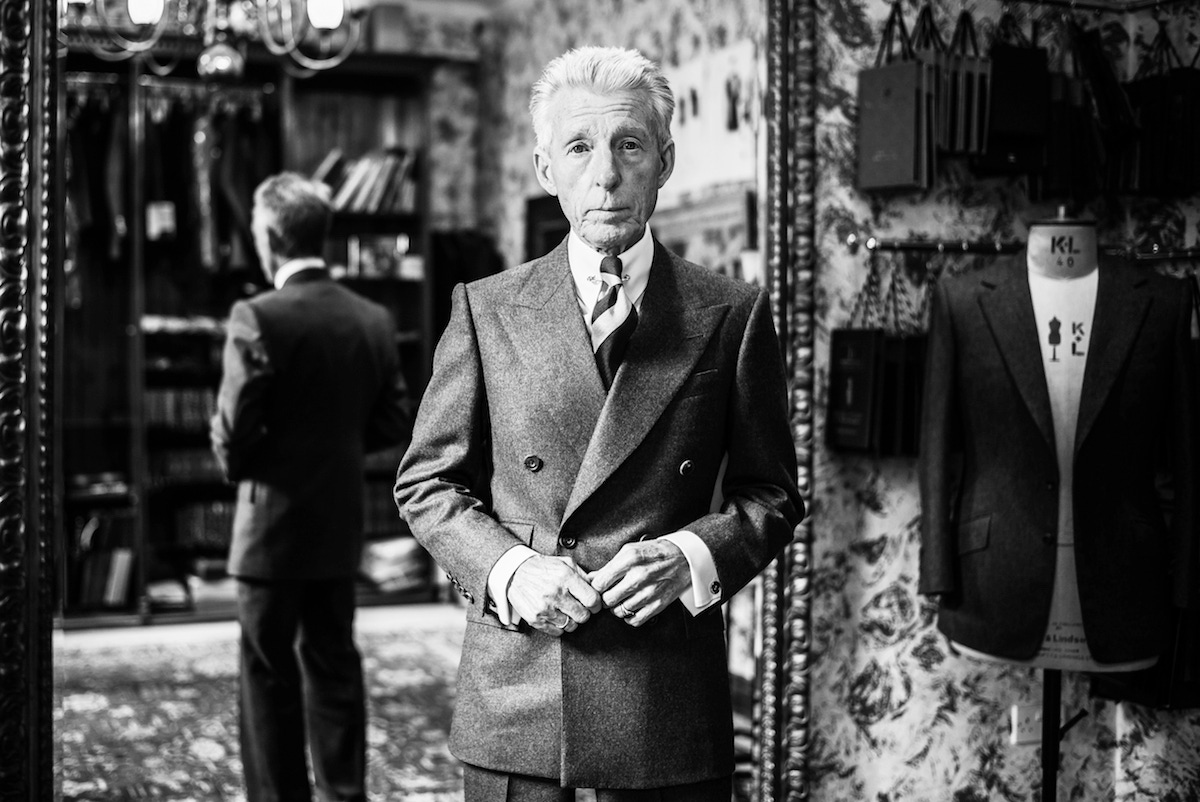

Never complacent when it came to looking the part, Best opened what would become the first of many boutiques, Edwardia, in Manchester in 1966. During this era, he emulated the look of rock-style pioneers such as The Kinks and The Who at their most dapper: think understated button-down shirts combined with slim-cut tweed slacks (not for him the gaping, gaudy excess of flower power) and the finest leather Chelsea boots. Even when his body was starting to decay from alcoholism, shots of Best in a loose-fitting polo, sporting what would later become a Britpop haircut, depict a man who remained an impressive-looking specimen well into his destructive years. Even as recently as 2003, enough of his sartorial nous remained for him to team up with Ben Sherman and design his own range of clothes - albeit a retro collection.

Armed with the looks, the threads, the lolly and the lifestyle, it was never going to be hard for him to indulge his almost adolescent fixation with the opposite sex. He drove his endless succession of blondes - not to mention his ex-wives Alex Best and Mary Stavin - to despair with his boozing, gambling and rampant swordsmanship. For a long time, no one could decide how many Miss Worlds he'd bedded, until he cleared the matter up in his tellingly named autobiography, The Good, the Bad and the Bubbly, in 1996: 'It was only four. I didn't turn up for the other three.'

Of course, 'flawed' is a grossly understated word to describe a man who was pathologically unable to stop taking excess to excess. He drove cars while gloriously wrecked, one time crashing into a lamp-post outside Harrods after a huge bender. He inflicted endless suffering on his long-term lovers, and sometimes strayed across the line between swashbuckling womaniser and callous cad - one such occasion being, if the rumours are to be believed, when he took a bride upstairs from a hotel bar while his teammates plied her husband with drinks.

On a lighter note, his naff late-'60s Cookstown Sausages TV ads, if you adhere to Kantian ethics, drew more collective furrowing of the human brow than all his rampant womanising combined. On a far, far more serious note, he poisoned the new liver which most seriously ill people never get granted. Most unforgivably of all, he beat and battered those who, when he was not inebriated, he loved most. The only penance he paid for his crimes were the 12 weeks he spent in prison (from Christmas 1984, for drink-driving and assaulting a policeman), the carving knife rammed into his backside by his first wife (which he undoubtedly deserved) and his premature death.

And yet half a million people lined Belfast's streets when they laid him to rest. Since then, he's been immortalised on a limited- edition pound note, had Belfast's airport named after him and - admittedly, more dubiously - had a musical, currently running in Belfast, written about his life. Anywhere between sober and only half-cut, he was amiable, funny, equipped with a charming mixture of impudence and insouciance. He was severely ill, yet never cashed in his adulation for sympathy from his public. Why? Perhaps because he knew he'd had one hell of a time making himself ill. His deeds on the pitch will continue to delight and inspire for time immemorial.

It was a life that should teach all men of substance to sip heartily from, but know when to put down, the cup of Bacchus. But a life that deserves such a pejorative single-word epitaph as 'tragic'? Then bring on a carefully measured dose of calamity, please.