Setting The President

John F. Kennedy’s dress sense was central to his public persona, forming no small part of this truly modern president’s enduring iconography.

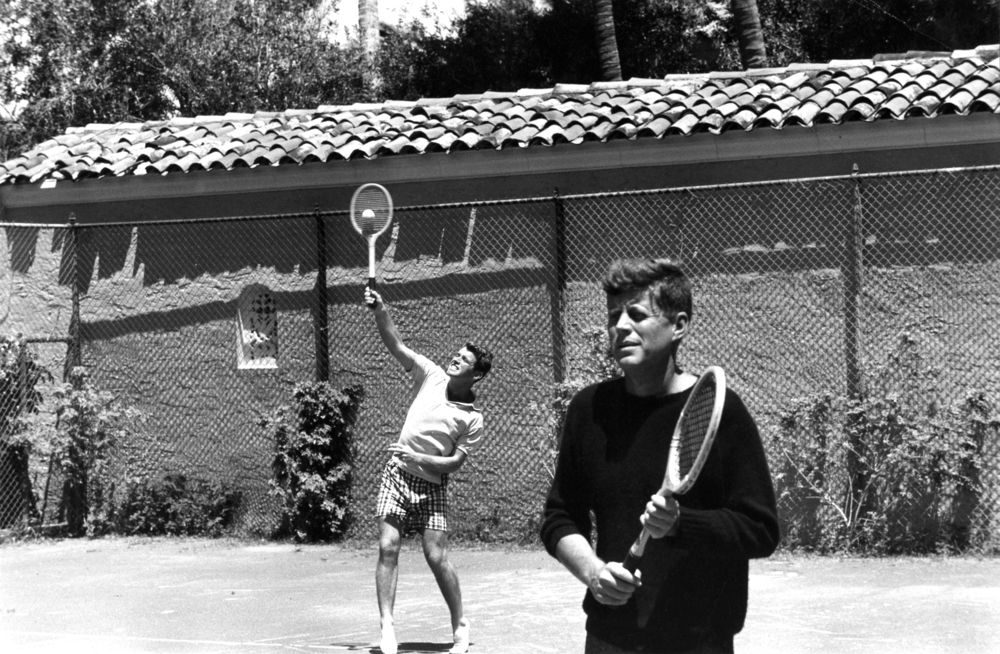

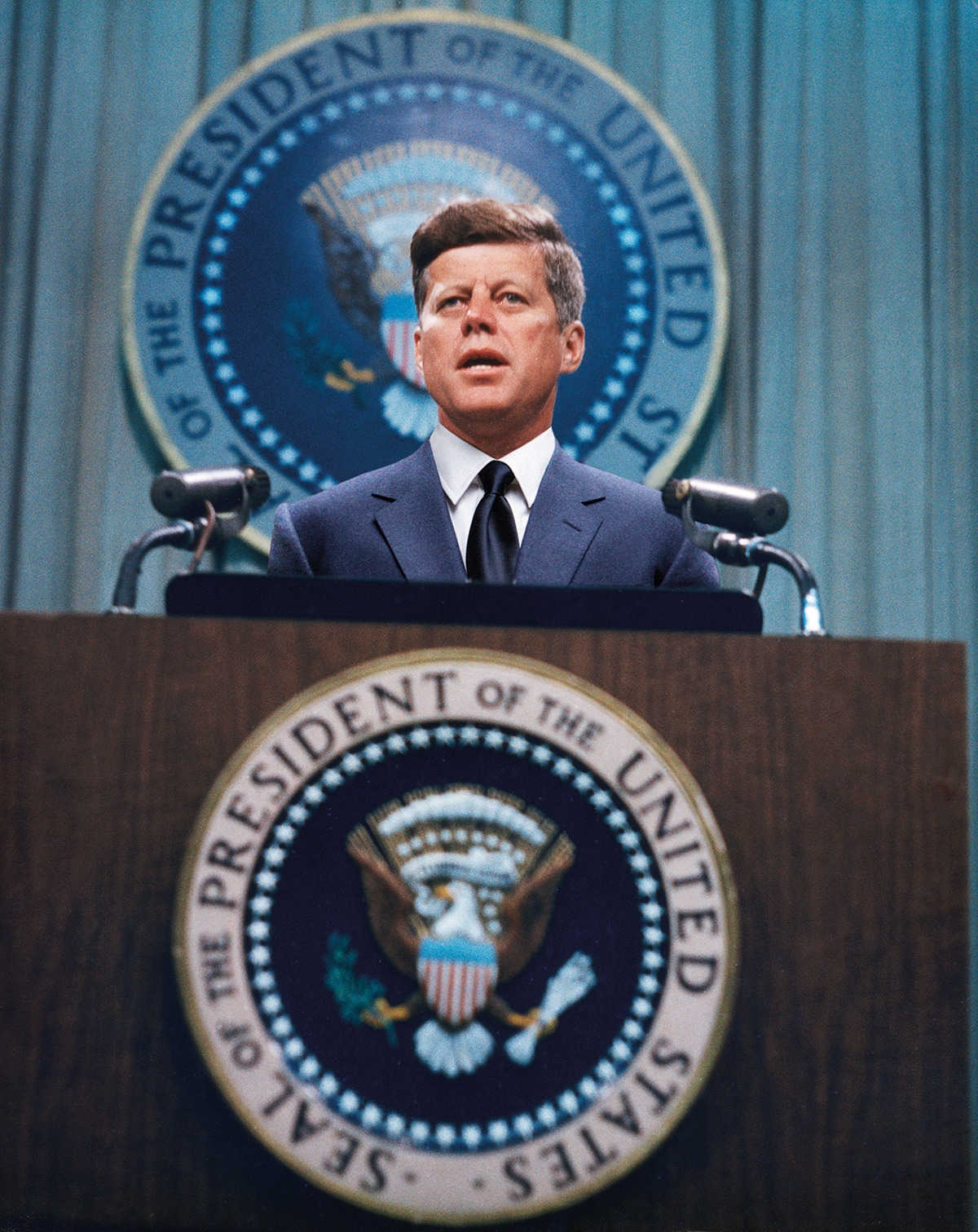

Photographs of John F. Kennedy generally fall into two categories. In the first, we see him at his family’s Cape Cod retreat, sleeves rolled up, wearing khakis grass-stained from touch football, or clad in Nantucket Reds and sunglasses sailing the sea. In the second, his presidential kit, we see another man altogether. Kennedy’s dark suits hang with a certain awkwardness, the shoulders large and high, his two chest buttons both fastened.

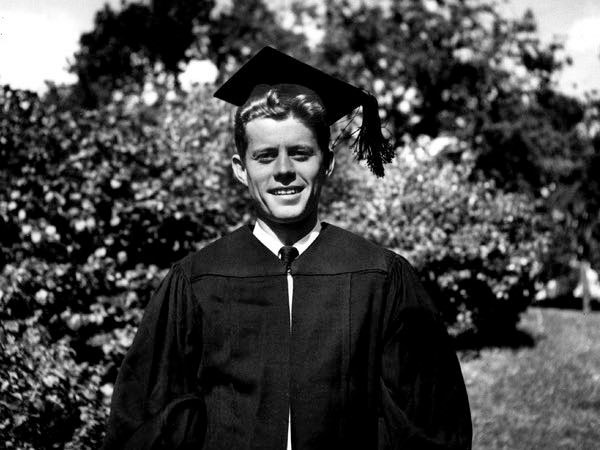

Though both are equally iconic, these two images of JFK reveal the sartorial differences between the man’s public and private lives. Privately, he was the Choate- and Harvard- educated scion of a patrician American dynasty, while publicly, he was a progressive young Democrat, commander on the frontlines of the Cold War, and careful crafter of a public image in the new age of television.

This schism made JFK both the ultimate preppy President — his administration reigned at the height of the Ivy League Look — and an ironic hastener of the look’s decline, undermining the very style he so perfectly embodied. Though Kennedy could hide neither his Catholic faith nor his Brahmin accent, this first great image crafter of the TV age strengthened his broad appeal with two sartorial gestures: He would wear two-button suits instead of three-button sack models, and he would eschew buttondown collars. The result, noted LIFE magazine in 1961, was that the President’s clothes “fail to conform to current Ivy League fashion”.

Before becoming a style setter, Kennedy started out as a ragamuffin. “As a young man he was notorious for his personal disorder,” writes Neil Steinberg in his book Hatless Jack: The President, the Fedora, and the History of American Style. “His boarding-school roommates complained of his messiness, particularly with clothes. He would show up with his shirt untucked, or without socks, or wearing a rag of a necktie.”

Prior to his marriage to Jacqueline Bouvier in 1953, “Kennedy had been a sloppy dresser who favoured baggy suits clashing shirts and ties, and ratty tennis shoes,” according to historian Thurston Clarke.

With Jackie’s guidance, Kennedy’s style evolved into a paragon of simplicity and understatement. His casual weekend mufti was collegiate and Northeastern — Shetland crewnecks, penny loafers sans socks, white T-shirts, polo shirts and chinos, with a notable absence of pattern. His suits were solids or light stripes, shirts almost always white with a short straight collar, his ties discreet reps and clubs. Like Steve McQueen, another charismatic public figure with subdued taste, Kennedy gave his clothes style, rather than the other way around, a testament to the idea that clothes should never upstage their wearer.

Sartorial simplicity suited Kennedy best because he had star quality, an air of innate dignity, recalled his physician Janet Travell, “that was the product of personal reserve, self-respect, style and a distaste for ostentation”. But there was something else. With his sunglasses and convertibles, ironic wit and military heroics, Kennedy had something no American leader had ever had before: cool.

Much of Kennedy’s cool came from his hair, a Samson’s mane of potent charisma and something Kennedy famously avoided covering with headwear. “In a hat he looked far older and almost unrecognisably ugly,” writes Steinberg. “And he knew it.”

JFK’s effect on American taste was palpable. “Kennedy sets the style, taste and temper of Washington,” wrote GQ in 1961. “Cigar sales have soared (Jack smokes them). Hat sales have fallen (Jack does not wear them). Dark suits, well-shined shoes, avoid buttondown shirts (Jack says they are out of style).”

As GQ points out, Kennedy set styles as much for what he negated as for what he advocated, and he stood in favour of two-button suits as much as he stood against buttondown collars. Historians have suggested that Kennedy preferred two-button suits because they better accommodated his back brace. Paul Winston, who made suits for Kennedy while working at his family’s legendary clothing company Chipp, recalls Kennedy wearing a brace during fittings at New York’s Carlisle Hotel. However, he says the button stance would not have mattered.

What is more likely is that Kennedy felt that while he couldn’t hide his privileged background in a television age that required mainstream appeal, he could at least obviate his image through dress by wearing suits less redolent of the Eastern Elite and more becoming for a man in the limelight of international affairs. When asked if suits for the newly elected President would be two-button, tailor Sam Harris said, “Certainly, two-button. We don’t follow Ivy League or beatniks. We make gentlemen’s clothes.”

“That old saying that clothes make the man? Not really. I think the man makes the clothing.”And when it came to shirt collars, Kennedy mocked his brother Robert in the press, telling LIFE, “He’s still wearing buttondown shirts; they went out at least three years ago,” and told friend and confidant Paul Fay that his buttondown collars were “too Ivy League”. Privately preppy, publicly the leader of the free world, Kennedy was always an icon. But in the annals of style history, JFK is less an example of a well-dressed man than a man with tremendous charisma, and for such men, understatement is always the best frame. “Kennedy was a handsome and important man,” remembers Paul Winston. “That old saying that clothes make the man? Not really. I think the man makes the clothing.”