Jackie Kennedy and Lee Radziwill: Sisters of Providence

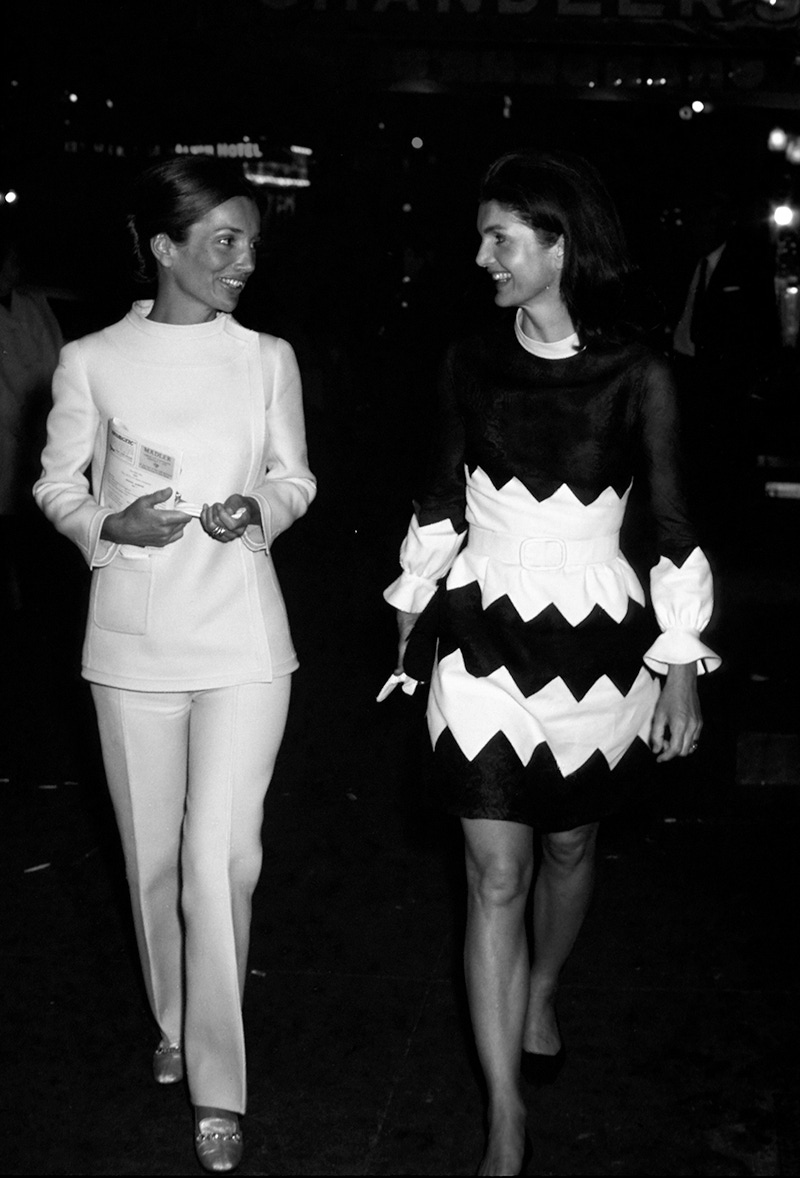

The Rake charts the privileged, prominent, marriage-rich lives of the Bouvier sisters — Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy Onassis and Caroline Lee Bouvier Canfield Radziwill Ross.

As a measure of the triumph of popular culture, it’s hard to beat; type the words ‘Bouvier sisters’ into Google, and the first entries that come up are devoted to Patty and Selma, Marge’s chain- smoking, slatternly siblings in The Simpsons. This, however, would probably suit the previous claimants of the title down to the ground. While Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy Onassis and Caroline Lee Bouvier Canfield Radziwill Ross (best known as Lee Raziwell) were seemingly trained to seduce rich and powerful men from their coming-of-age, thereby accruing a level of public fascination in the US and beyond that would have kept a thousand Perez Hiltons micro-blogging till steam poured from their laptops, they went about their picaresque business in a manner that, in an age of sex tapes and papped up-skirt shots, seems impossibly reticent and discreet. But then, that was their birthright.

The Bouviers were third-generation French Catholic immigrants who, in the intensely class-conscious America of the ’20s, felt it necessary to fantasise about their ancestry, elevating their shopkeeper forebears into nobles. “I don’t know how they got away with it,” said author and essayist Gore Vidal, friend — and relative — to Jackie and Lee (in the merry-go-round common among the WASP elite at the time, their mother Janet would later marry Vidal’s stepfather, Standard Oil heir Hugh D. Auchincloss). “[The press buying this idea] that they were somehow Plantagenets and Tudors — it was just nonsense. They were pretty lowly born.”

Such myth-making, however, would feed into both sisters’ ideas of themselves as embodiments of an exceptional mantle. Jackie (born 28 July 1929) and Lee (3 March 1933) — or ‘Jacks’ and ‘Pekes’ as they were known in the family — cultivated an air of apartness from the beginning: as Jackie later remarked to society bandleader Peter Duchin, “We’re both outsiders.” Not that this made the sisters feel inferior; quite the contrary. They never felt it necessary to follow the society herd, and felt more of an affinity with artists and misfits. Of the men who they wouldbecome inextricably linked with — John F. Kennedy, Aristotle Onassis, Truman Capote — not one could remotely be described as a WASP.

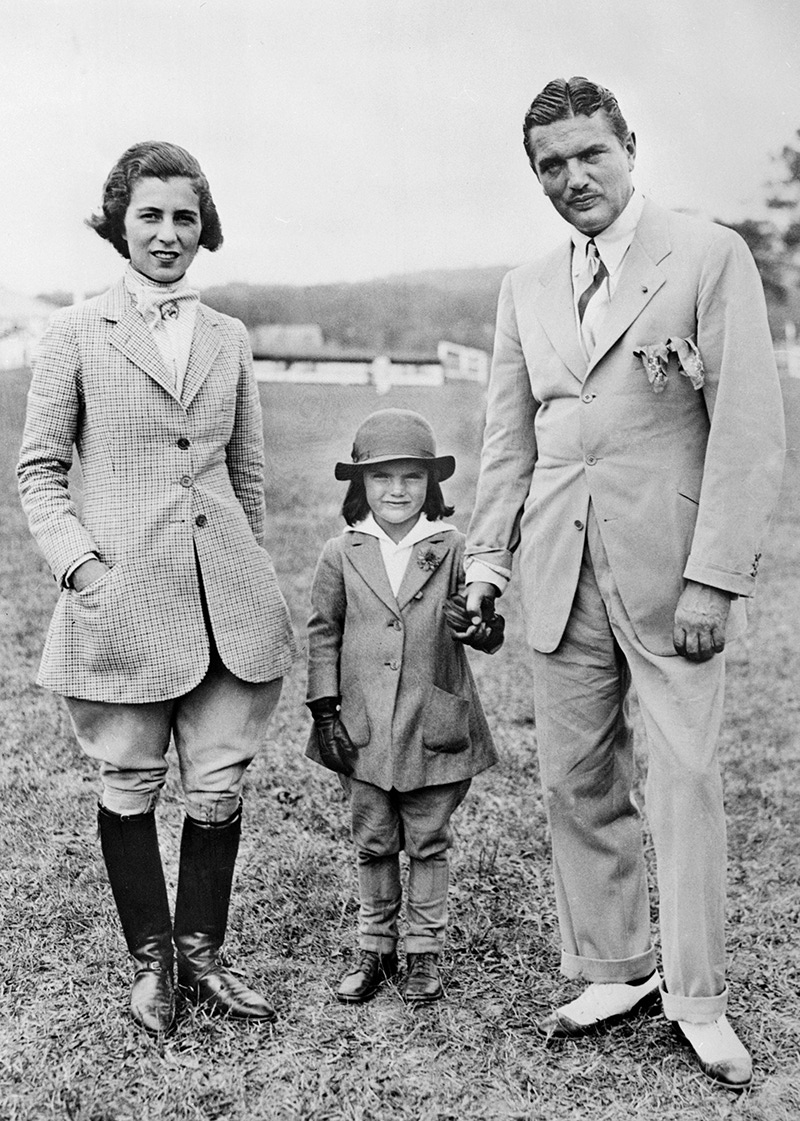

The other strain running through the sisters’ lives was the family’s sexual politics, with power emanating from the dominant male, and the women left to dance attendance. They had two spectacular role models on hand. Their paternal grandfather, Major John Vernou Bouvier Jr., known to all and sundry as ‘The Major’, was a dapper, expansive former trial lawyer who presided over the summer household at Lasata, in then-just-fashionable East Hampton, a stucco, ivy-clad house on 12 acres complete with tennis court, vegetable garden and stabling for eight horses. The name is Indian for ‘place of peace’, a comprehensive misnomer as far as the explosive Bouviers were concerned. The Major, stone- deaf, was given to loud explosions of temper — “Goddamn it to hell!” — while keeping his Poirot-style moustache impeccably waxed and roaring off to church in his red Nash convertible.

But while the sisters loved their grandfather, they adored their father, the glamorous, larger-than-life figure of John Vernou Bouvier III, a Wall Street stockbroker known as ‘The Sheikh’ or, more commonly, ‘Black Jack’, in honour of his saturnine complexion and thick, raven hair with arrow-straight parting. With his pencil moustache and piercing blue eyes, he was often mistaken for Clark Gable; and, with his undisciplined and self-indulgent lifestyle, it was easy to imagine him declaiming: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” (The vexed Major frequently threatened to disinherit him, a sanction that yielded diminishing returns).

Black Jack was incorrigibly vain — a friend, visiting him for a weekend at the Swordfish Club in Bridgehampton, was struck by the fact that he had hung six photographs of himself on the wall — and honed his muscular physique by working out at the Yale Club, sunbathing naked at one of the windows of the Bouviers’ rent-free, 11-room duplex on Park Avenue, or running round the Central Park reservoir in a bespoke rubber suit. His daywear was no less impressive — immaculate chalkstripes and Brooks Brothers shirts for the office, gabardine suits for the East Hampton summer. But Black Jack was also a compulsive gambler, womaniser and drinker, serenely uninterested in intellectual or cultural pursuits, with an abysmal academic record to match. Proud as he was of his wife Janet’s looks, chic and — most especially — prowess as a horsewoman, he was incapable of resisting temptation or self-gratification, shipping his family off for the summer and staying behind to throw parties for showgirls in the city. Onlookers remarked that he was more like a lover than a father to his daughters — irresponsible, intolerant of boredom, petulant, demanding. Not surprisingly, this caused conflict for both sisters as they sought his vacillating attention.

“Jackie’s relationship with Lee was very much S&M, with Jackie doing the S and Lee the M,” opined Gore Vidal of their mixture of closeness and intense rivalry. Unfortunately for Lee, there could only be one winner; while Black Jack doted on both daughters, deliberately stirring the pot at family gatherings by lathering effusively inappropriate praise on one or another of them, which nonplussed bystanders referred to as “Vitamin P” (“Lee’s going to be a real glamour girl someday. Will you look at those eyes and those sexy lips of hers?”), his passion for Jackie (and vice versa) was overriding and semi-incestuous. “Jackie was a brilliant horsewoman and he was always planning on which hunt team she could go into, which class she could join,” recalled Lee later. “Meanwhile, I was falling off my pony as it continually refused a fence. I couldn’t live up to what he wanted, which hurt, because I revered him.”

The inevitable Bouvier split was as bitter as it was public. On 26 January 1940, the New York Daily Mirror broke the news under the headline ‘Society Broker Sued For Divorce’, and for good measure, published details — apparently furnished by Janet’s lawyer — of Black Jack’s conquests, with dates and photographs. It was an early taste of tabloid-dirty-washing-in-public, anathema to the don’t-ask-don’t-tell WASP ethos in which the sisters were steeped. “It was the very worst divorce I’ve heard about and watched,” recalled Lee later, “because it was relentless, with myself and Jackie pulled in different directions all the time.”

The fallout from their toxic upbringing would mark the sisters in different ways. Lee, ever playing second-fiddle, would try on various careers like ostentatious but ill-fitting hats, before settling on the newly minted appellation of socialite; for Jackie, the stakes were higher. The ruins of her parents’ marriage left her with deep insecurities, repressed anger and a fawnlike shyness of the world beyond a circle of trusted intimates. Conversely, she would always be irresistibly drawn to the most powerful, successful man in a room (a cousin remarked of her partiality to a man like her future father-in-law, Joseph P. Kennedy, “If Jackie was at the court of Ivan the Terrible, she’d say, ‘Ooh, he’s been so misunderstood...’”) And Black Jack had some sage advice for her future husband, John F. Kennedy: “If you have any trouble with Jackie, put her on a horse.”

It’s not known if JFK ever followed Black Jack’s counsel, but what is certain is that, in the golden, hope-invested, alpha-male, emotionally feckless 35th US President, Jackie had found an Irish Catholic mirror-image of her profligate father, which allowed her not only to remain stoic in the face of his serial affairs, but also to

set the template for the dignified, decorous role that subsequent First Ladies aspired to but rarely equalled. She was a mere 31 when she assumed the office, satisfying her frustrated intellect by restoring dilapidated White House interiors, becoming a fashion icon, and morphing into the ultimate hostess: when Soviet Premier Khrushchev was asked to shake Kennedy’s hand for a photo, he turned to Jackie and leered: “I’d like to shake her hand first.”

However, the apotheosis of Jackie-as-icon occurred after the assassination of JFK in 1963, when she was transformed into a Mater Dolorosa for a nation delirious with grief for its slain messiah. It wasn’t just the grace notes and the righteous anger — slipping her wedding ring onto the president’s finger as he lay in his casket, saying “Now I have nothing left”; wearing the pink suit stained in her husband’s blood while standing alongside Lyndon Johnson as he took the oath of office, telling his wife Lady Bird “I want them to see what they have done to Jack” — it was also Andy Warhol’s immortalisation of her, serially screenprinted in her widow’s weeds, and that, as Lady Jean Campbell commented in the London Evening Standard, “Jacqueline Kennedy has given the American people one thing they have always lacked: majesty.”

It was Jackie who compared the Kennedy years in the White House to Camelot in a Life magazine interview, revealing that the president often played the title song of the Lerner and Loewe musical before retiring to bed. This vision was only slightly tarnished when she left the US following the death of Robert Kennedy in 1968, fearing for the safety of herself and her children, to marry the wealthy and ruthless Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, who ended his relationship with Maria Callas to accommodate her.

Lee, meanwhile, had followed a more peripatetic route, divorcing her first publisher husband to marry the Polish prince Stanislaw Albrecht Radziwill in 1959 (only to divorce again in 1974). She attempted to forge a career as an actress in the 1960s, but dismal notices for her performances in the dinner theatre production of The Philadelphia Story and the TV film Laura nipped that in the bud. However, Truman Capote, then riding high on his fame and notoriety, had written the screenplay for Laura, and adopted Lee as one of the high-society muses, along with Katharine Graham and Babe Paley, that he chaperoned and groomed and referred to as his “swans”. She was one of the innumerable guests of honour at Capote’s legendary Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in 1966, and became a kind of party mainstay and celebrity totem, accompanying Capote when he covered the Rolling Stones’ US tour in 1972.

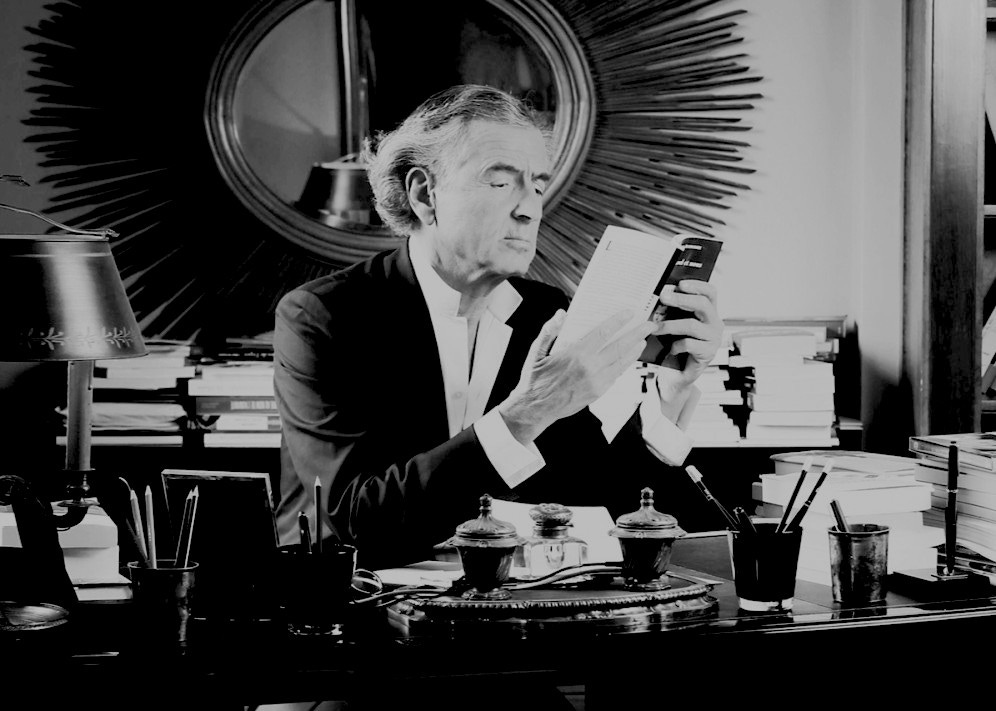

As both sisters came to define the parameters of modern celebrity culture, so they would experience its dark side in the ’70s. Jackie, widowed for a second time after Onassis’ death in 1975, moved back to New York and became a book editor at Doubleday. She was now dating Maurice Tempelsman, a Belgian-born industrialist and diamond merchant, but she remained a subject of endless speculation and gossip fodder; the proto- paparazzi photographer Ron Galella became her unofficial stalker, snatching hundreds of off-duty pictures of her, before she won a restraining order against him. Lee had become embroiled in a libel case that Gore Vidal had brought against Capote, after the latter, an outsider in ways that Jackie and Lee could only dream of, had accused Vidal of being thrown out of a 1961 White House function after putting his arm around Jackie and insulting her mother, adding that Lee herself was the source of the story. Her response was imperious — “They’re two fags; it’s just the most disgusting thing” — goading Capote to turn attack-dog, accusing Lee of jealousy towards her sister (“The princess kind of had it in mind that she was going to marry Mr. Onassis herself”), and eviscerating her break-up with photographer Peter Beard (“He met this chick with a little less mileage on her”), and on-again- off-again engagement to San Francisco hotelier Newton Cope (“She said he was a nobody who was riding on her coattails”). Friends tut-tutted in public, while conceding in private that Capote’s charges sounded all too plausible; Lee remained silent.

In their latter years, the sisters maintained their lifelong commitment to discretion. Jackie died in 1994, of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; her son, the ill-fated JFK Jr., announced that “she died surrounded by family and friends and the things she loved. She did it her own way, on her own terms.” Lee has been through her third divorce — from film director and choreographer Herbert Ross — and is retired from her job as PR executive for Giorgio Armani. She’s also the author of an autobiography called Happy Times; thanks to the legacy of Black Jack’s ministrations and the ambivalent nature of their WASP inheritance — defined by the writer Tad Friend, in reference to his own family, as “limpid surface, measureless depths”, the truth of her and Jackie’s gilded, conflicted, spotlit lives will forever be a little more complex and ambiguous than that.