Six of the Best: John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman

John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman's 1963 jazz collaboration came about in unlikely, arbitrary circumstances. Yet this seminal album's six sublime, worldly-wise tracks could make the most ardent sceptic believe in destiny.

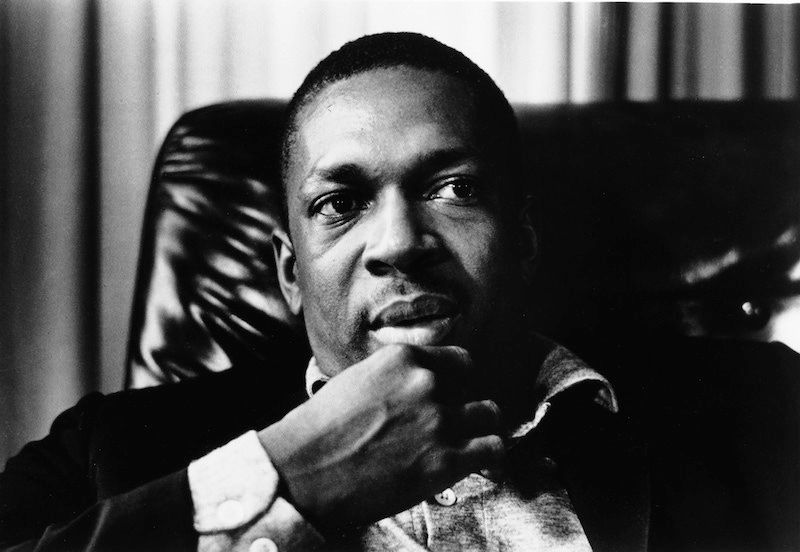

There are few jazz albums a man might choose from for amorous purposes. Most of the best are the work of instrumentalists; certainly, hardly any featuring male singers fit the bill. One, however, does; one that establishes such a lofty standard, subsequent attempts to top or even equal it seem doomed from the outset. John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, recorded in 1963 on the Impulse! label, remains perfectly suited to any encounter in which romance is meant to play a part. A mere half-hour of superbly selected songs by the likes of Irving Berlin, Billy Strayhorn and Rodgers and Hart, the program never becomes insistent, intrusive or self- involved. Six subtle yet fully dramatised renditions of highly literate lyrics and sophisticated melodies create a narrative arc that moves through successive stages of hope, promise, devotion, disengagement, acceptance and memory. John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman was recorded in 1963 in a lone studio

meeting between one of the most

ennobled icons in jazz at that time and

a lesser-known vocalist who, on the basis of this collaboration alone, left an indelible mark. The story behind it is remarkable for being mundane rather than glamorous. And, although the music is now nearly 50 years old, it has lost none of its glow: rather, it has aged like fine wine.

Throughout the album, the baritone Hartman, tenor saxophonist Coltrane (also known as Trane) and his peerless rhythm trio - pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones - make music that seems to be so in-the-moment, so up-close-and-personal, that it conjures, upon first hearing, a sense of shared intimacy. Hartman's voice embodies masculine maturity, and here it is cushioned by filigreed piano accompaniment, rhythms brushed lightly with implication, basslines so soft they go unnoticed, beguiling saxophone solos and murmured obbligati. Those are the seductive attributes of Coltrane/Hartman. When used as background music in conjunction with low lights and late-night cocktails, the recording is like a charming gift that proves the giver is truly in touch with the recipient's desires.

Coltrane/Hartman is unique in jazz history as the only recording on which Coltrane, the most relentlessly experimental and individual member of the '60s jazz generation, collaborated with a singer. It is also the performance with which Hartman secured his enduring reputation. Considering the somewhat off-the-cuff way the production came about, Coltrane/Hartman could be considered an anomaly, a lucky accident, or kismet. The chances of anyone consciously planning and executing such an album are akin to those of an arranged marriage igniting into a passionate inferno on the wedding night: slim to none. No, this is how masterpieces - and, incidentally, most long-term relationships - are born: from the unpredictable confluence of disparate circumstances.

When a project with a singer, any singer, was first proposed to Coltrane, it was posited as something of a retreat from his recent stylistic developments. Having emerged from journeyman anonymity in the mid-'50s to a spotlit position as a featured player with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, Trane had, in 1960, scored an unexpected jazz hit with his soprano saxophone recasting of 'My Favorite Things', and had established his mastery of the tenor sax by racing through complex chord progressions on his original compositions such as 'Giant Steps', recorded for Atlantic Records.

In 1961, he left Atlantic for a newly established label, Impulse! Coltrane's first effort for this imprint, guided by house producer Bob Thiele, was Africa/Brass, which stripped the formal harmonic underpinnings he'd been flaunting thus far, down to a fundamental throb and drones. Against, over and through a relatively open field, Coltrane blew variations of simple themes with increasing density, volatility and volubility, sometimes breaking into harsh cries, atonal runs or extreme registers of his horn.

Trane's new music was a breakthrough into territory still being explored by improvisers today. However, critical and public reception to his turn was divided. An influential editor at the jazz magazine Down Beat called Coltrane's direction 'horrifying', 'anti-jazz', 'gobbledegook'. Thiele retaliated for his artist by conceiving three albums that would solidify Coltrane's mainstream bona fides: one made up of well-known ballads, a second with the highly esteemed Duke Ellington and the third with a vocalist.

While Coltrane's sound had evolved as a plunge into the unknown, Johnny Hartman, some 15 years into his career, had held fast to a style that was receding in popularity. A native of Chicago, Hartman first gained notice after returning from military service during World War II to sing in the big bands of Earl Hines and Dizzy Gillespie. His role model was Billy Eckstine, one of the first black male entertainers to be openly regarded as a heartthrob by white women in America. Early on, Hartman, tall and handsome, was hailed as a 'Bronze Sinatra', a crooner of slow- to mid-tempo swing whose articulation of language and placement of pitch were proper and precise.

The 1950s, however, witnessed a sea change in popular music trends as the rougher vernaculars of rhythm and blues, Doo-wop, rockabilly and rock 'n' roll won over young audiences throughout America, and soon, the world. Sinatra, Eckstine, Tony Bennett, Nat King Cole and several others sustained careers based on the adult polish of their styles, but Ray Charles, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke subverted their dominance. As the big-band era ended, Hartman adapted by working with small combos in supper clubs and cabarets, while recording sporadically.

In 1959, he went to Europe 'to stay employed', as he put it years later. Intending to visit for two weeks, he stayed 11 months. He worked in England, Belgium and Germany, and appeared (according to Dr Gregg Akkerman's recently released biography, The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story)at least three times as a guest on British television. Eventually, he ran afoul of the musicians' union's staunchly protectionist rules; otherwise he might have opened a singing studio and perhaps hosted a TV programme of his own. Back in the States, he found that bookings were scarce for an urbane black man such as himself, who preferred refinement to rawness. A three- week tour of Japan, singing with drummer Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, was a high point of this period for Hartman. He was there when the call came from Bob Thiele, inviting him to collaborate with Coltrane.

'Johnny Hartman - a man that I had just stuck up in my mind somewhere - I just felt something about him,' Coltrane later said of his one-time-only partner. 'I liked his sound, I thought there was something there I had to hear.' In another interview, Coltrane offered another reason for his enthusiasm: 'He's a fine singer, and I wanted him to make a comeback.' The two had never worked together. They'd both been in Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra, but at different times.

Although Coltrane was so sure he wanted Hartman that he rejected Thiele's suggestions of other singers including Sarah Vaughan, Hartman had his doubts. 'I didn't know if John could play that kind of stuff I did,' he told writer Frank Kofsky a decade after the fact. 'So I was a little reluctant at first. Then John was working at Birdland, and he asked me to come down there, and after hearing him play ballads the way he did, man, I said, 'Hey, beautiful.' So that's how we got together.'

Jazz instrumentalists - perhaps tenor saxophonists, especially - are adept at portraying elegance, experience and sensitivity: ideal qualities in a lover. The best of them (for instance, Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Lester Young, Stan Getz and Dexter Gordon) acquire the ability to manipulate almost human-voice-like aspects from their horns, and control the dynamics of their breathing to evoke feeling over the course of decades of close listening. It's about delicate yet deliberate physical activity, and spontaneous, interactive self-expression. If such musicians have a strong-enough repertoire and perform thus, at the peak of their game, their music may live forever.

In contrast, most song stylists are irrevocably identified with their specific historical eras. When a certain mood is struck, one does not want one's romantic partner distracted by the voice of another man, or by her wondering if the album had been borrowed from your grandfather. Timelessness is what we're after when we want to take our own sweet time. A traditional pose, one that projects unquestioned credibility, is required. This is what was so right about the Coltrane/Hartman pairing. In 1963, Coltrane was 37, fairly young, yet even a cursory encounter with his music makes it clear he was a person containing profound depths. Hartman was 40, and not susceptible to passing fads. They may have held contrasting positions on an aesthetic continuum, but their gravitas was a match.

And so when, after a brief piano introduction provided by McCoy Tyner, Hartman intones, 'They say that... falling in love... is wonderful', with an air of faint disbelief overridden by ineffable yearning that the possibility be true; as Elvin Jones swishes wire whisks over his snare's drumhead, while Coltrane enters with a forthright statement of the same sentiment: we hear communion comparable to brothers bearing a single message.

The 1950s, however, witnessed a sea change in popular music trends as the rougher vernaculars of rhythm and blues, Doo-wop, rockabilly and rock 'n' roll won over young audiences throughout America, and soon, the world. Sinatra, Eckstine, Tony Bennett, Nat King Cole and several others sustained careers based on the adult polish of their styles, but Ray Charles, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke subverted their dominance. As the big-band era ended, Hartman adapted by working with small combos in supper clubs and cabarets, while recording sporadically.

In 1959, he went to Europe 'to stay employed', as he put it years later. Intending to visit for two weeks, he stayed 11 months. He worked in England, Belgium and Germany, and appeared (according to Dr Gregg Akkerman's recently released biography, The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story)at least three times as a guest on British television. Eventually, he ran afoul of the musicians' union's staunchly protectionist rules; otherwise he might have opened a singing studio and perhaps hosted a TV programme of his own. Back in the States, he found that bookings were scarce for an urbane black man such as himself, who preferred refinement to rawness. A three- week tour of Japan, singing with drummer Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, was a high point of this period for Hartman. He was there when the call came from Bob Thiele, inviting him to collaborate with Coltrane.

'Johnny Hartman - a man that I had just stuck up in my mind somewhere - I just felt something about him,' Coltrane later said of his one-time-only partner. 'I liked his sound, I thought there was something there I had to hear.' In another interview, Coltrane offered another reason for his enthusiasm: 'He's a fine singer, and I wanted him to make a comeback.' The two had never worked together. They'd both been in Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra, but at different times.

Although Coltrane was so sure he wanted Hartman that he rejected Thiele's suggestions of other singers including Sarah Vaughan, Hartman had his doubts. 'I didn't know if John could play that kind of stuff I did,' he told writer Frank Kofsky a decade after the fact. 'So I was a little reluctant at first. Then John was working at Birdland, and he asked me to come down there, and after hearing him play ballads the way he did, man, I said, 'Hey, beautiful.' So that's how we got together.'

Jazz instrumentalists - perhaps tenor saxophonists, especially - are adept at portraying elegance, experience and sensitivity: ideal qualities in a lover. The best of them (for instance, Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Lester Young, Stan Getz and Dexter Gordon) acquire the ability to manipulate almost human-voice-like aspects from their horns, and control the dynamics of their breathing to evoke feeling over the course of decades of close listening. It's about delicate yet deliberate physical activity, and spontaneous, interactive self-expression. If such musicians have a strong-enough repertoire and perform thus, at the peak of their game, their music may live forever.

In contrast, most song stylists are irrevocably identified with their specific historical eras. When a certain mood is struck, one does not want one's romantic partner distracted by the voice of another man, or by her wondering if the album had been borrowed from your grandfather. Timelessness is what we're after when we want to take our own sweet time. A traditional pose, one that projects unquestioned credibility, is required. This is what was so right about the Coltrane/Hartman pairing. In 1963, Coltrane was 37, fairly young, yet even a cursory encounter with his music makes it clear he was a person containing profound depths. Hartman was 40, and not susceptible to passing fads. They may have held contrasting positions on an aesthetic continuum, but their gravitas was a match.

And so when, after a brief piano introduction provided by McCoy Tyner, Hartman intones, 'They say that... falling in love... is wonderful', with an air of faint disbelief overridden by ineffable yearning that the possibility be true; as Elvin Jones swishes wire whisks over his snare's drumhead, while Coltrane enters with a forthright statement of the same sentiment: we hear communion comparable to brothers bearing a single message.

Hartman's tone, rising from a chamber near his heart to the tip of his tongue, bespeaks a longing to be joined in the test of a tender hypothesis. He sings as a man who is unsure such a thing as 'love' exists, but is more than willing to give it a try. The lightness with which he floats key words, and the way in which he lingers over such a neutral conjunction as 'and', beckon but do not demand response. Coltrane's chorus on sax rephrases, decorates and slightly expands upon the tune by Irving Berlin, but completely complements what Hartman has sung and returns the song to him for an even more hopeful iteration.

The second track on Coltrane/Hartman, 'Dedicated to You', written by Sammy Cahn, Saul Chaplin and Hy Zaret, is a pure offer of devotion, put forth with the same wistful, ready-to- be-rejected attitude as 'They Say It's Wonderful'. Hartman and Coltrane again express themselves with a limpid air of quietude. 'A lifetime would be just one heavenly day,' Hartman purrs to the subject of his passion. If that encomium doesn't earn him affection, his cause is lost.

But it isn't! 'My One and Only Love', which sees Coltrane first outlining the tune, is a simply beautiful testimony of consummation. There is no jumping for joy in either the saxophonist's or Hartman's declaration of ardour fulfilled. The manner of their gratitude is awed appreciation, not giddy overreaching. First recorded by Frank Sinatra in 1953, and many times since (including by Paul McCartney), the Coltrane/ Hartman version of 'My One and Only Love' is definitive: the core of the album, in fact.

Hartman's tone, rising from a chamber near his heart to the tip of his tongue, bespeaks a longing to be joined in the test of a tender hypothesis. He sings as a man who is unsure such a thing as 'love' exists, but is more than willing to give it a try. The lightness with which he floats key words, and the way in which he lingers over such a neutral conjunction as 'and', beckon but do not demand response. Coltrane's chorus on sax rephrases, decorates and slightly expands upon the tune by Irving Berlin, but completely complements what Hartman has sung and returns the song to him for an even more hopeful iteration.

The second track on Coltrane/Hartman, 'Dedicated to You', written by Sammy Cahn, Saul Chaplin and Hy Zaret, is a pure offer of devotion, put forth with the same wistful, ready-to- be-rejected attitude as 'They Say It's Wonderful'. Hartman and Coltrane again express themselves with a limpid air of quietude. 'A lifetime would be just one heavenly day,' Hartman purrs to the subject of his passion. If that encomium doesn't earn him affection, his cause is lost.

But it isn't! 'My One and Only Love', which sees Coltrane first outlining the tune, is a simply beautiful testimony of consummation. There is no jumping for joy in either the saxophonist's or Hartman's declaration of ardour fulfilled. The manner of their gratitude is awed appreciation, not giddy overreaching. First recorded by Frank Sinatra in 1953, and many times since (including by Paul McCartney), the Coltrane/ Hartman version of 'My One and Only Love' is definitive: the core of the album, in fact.

Which renders the next song, 'Lush Life', all the more tragic. Both the lyrics and the tune were written by Billy Strayhorn, whose sexual orientation may have increased his personal reticence during a repressed age, but did not hamper his long, creative alliance with Duke Ellington. A soliloquy full of vivid imagery and touching regret, the song had been recorded by Coltrane only two years earlier, and was added to the list of tunes considered for the album at the last minute. Coltrane and Hartman had heard Nat Cole's rendition on the car radio during the ride they shared on their way to record at Rudy Van Gelder's New Jersey studio, and had immediately agreed to try it. Hartman relates the sad story as if it's his own, concluding on a marvellously fragile note, which he holds steady as the musicians resolve in support.

'You Are Too Beautiful' follows up on the notion of Hartman, our protagonist, being left behind, although one might suspect that, since he's been so suavely in control up to this point, he's actually giving himself a way to disengage. Pianist Tyner shines on this track, with a fleetness in his solo that suggests escape more than self-sublimation. 'Autumn Serenade', the final track of Coltrane/Hartman, also depicts how a gentleman may think of love when it's over. With an exotic rhythm and Coltrane's most inquisitive effort, the track purports to recall a former splendour, but doesn't Hartman sound relieved, and free?

A popular legend, spread by producer Thiele and Coltrane's hagiographer Kofsky, among others, has it that the tracks on Coltrane/Hartman were, bar one, all captured on one take. Akkerman, in his Hartman bio, cites evidence to the contrary, which does not diminish the efficiency with which Coltrane, Hartman and the rest of the team created their tour de force. After checking the master takes, Coltrane returned to his microphone to add a phrase here and there. It makes no difference to the end result. Not one gesture on Coltrane/Hartman is out of place.

In 2005, commissioned by the Chicago Jazz Festival, singer Kurt Elling and saxophonist Joshua Redman attempted the daunting task of covering the Coltrane/Hartman material. The singer and his pianist Laurence Hobgood added strings to the original quartet arrangements, and included six more songs to flesh out the set. They performed the results subsequently on several occasions, including the Monterey Jazz Festival, and recorded it live at a concert for Jazz at Lincoln Center's American Songbook Series. It was released in 2009 as Dedicated to You: Kurt Elling Sings the Music of Coltrane and Hartman.

Which renders the next song, 'Lush Life', all the more tragic. Both the lyrics and the tune were written by Billy Strayhorn, whose sexual orientation may have increased his personal reticence during a repressed age, but did not hamper his long, creative alliance with Duke Ellington. A soliloquy full of vivid imagery and touching regret, the song had been recorded by Coltrane only two years earlier, and was added to the list of tunes considered for the album at the last minute. Coltrane and Hartman had heard Nat Cole's rendition on the car radio during the ride they shared on their way to record at Rudy Van Gelder's New Jersey studio, and had immediately agreed to try it. Hartman relates the sad story as if it's his own, concluding on a marvellously fragile note, which he holds steady as the musicians resolve in support.

'You Are Too Beautiful' follows up on the notion of Hartman, our protagonist, being left behind, although one might suspect that, since he's been so suavely in control up to this point, he's actually giving himself a way to disengage. Pianist Tyner shines on this track, with a fleetness in his solo that suggests escape more than self-sublimation. 'Autumn Serenade', the final track of Coltrane/Hartman, also depicts how a gentleman may think of love when it's over. With an exotic rhythm and Coltrane's most inquisitive effort, the track purports to recall a former splendour, but doesn't Hartman sound relieved, and free?

A popular legend, spread by producer Thiele and Coltrane's hagiographer Kofsky, among others, has it that the tracks on Coltrane/Hartman were, bar one, all captured on one take. Akkerman, in his Hartman bio, cites evidence to the contrary, which does not diminish the efficiency with which Coltrane, Hartman and the rest of the team created their tour de force. After checking the master takes, Coltrane returned to his microphone to add a phrase here and there. It makes no difference to the end result. Not one gesture on Coltrane/Hartman is out of place.

In 2005, commissioned by the Chicago Jazz Festival, singer Kurt Elling and saxophonist Joshua Redman attempted the daunting task of covering the Coltrane/Hartman material. The singer and his pianist Laurence Hobgood added strings to the original quartet arrangements, and included six more songs to flesh out the set. They performed the results subsequently on several occasions, including the Monterey Jazz Festival, and recorded it live at a concert for Jazz at Lincoln Center's American Songbook Series. It was released in 2009 as Dedicated to You: Kurt Elling Sings the Music of Coltrane and Hartman.

Asked how he approached such etched-in-stone material, Elling told The Rake, 'In an intuitive way, largely ignoring the weight of history or of perceived expectations.' He identified 'a golden voice and emotional transparency' as Hartman's unique contribution to the monumental album, adding, 'I believe that all the artists involved raised the level of their games simply by their mutual commitment to quality and to making the best of every musical encounter. Thanks to Trane, 'compassion' was the name of the game. Therefore, a certain clear-eyed tenderness shone through.'

John Coltrane died in 1967, having continued to probe the far reaches of music he could create with his saxophone. Johnny Hartman lived until 1983. After making four more albums produced by Bob Thiele, he spent the '70s and early '80s performing mostly in lounges and supper clubs, recording for small independent labels. In 1981, he was nominated for a Grammy for 'Best Male Jazz Vocalist' for an album titled Once in Every Life. In 1995, director Clint Eastwood used seven tracks from that record, which had fallen out of print, on the soundtrack of his film Bridges of Madison County.

Tenderness, compassion and emotional transparency are, indeed, impressions one takes away from an encounter with John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, as well as admiration for its subdued lyricism and psychological acuity. Then there's the sheer pleasure one takes from close engagement with an object of multifaceted, inexhaustible beauty. Such engagement may occur once in a lifetime, or sometimes, if you're lucky, more often. If the 'object' is another human with whom one wants to strike a spark, or perhaps kindle a fire with and enjoy some warmth, it's very good to have Coltrane/Hartman at hand.

Asked how he approached such etched-in-stone material, Elling told The Rake, 'In an intuitive way, largely ignoring the weight of history or of perceived expectations.' He identified 'a golden voice and emotional transparency' as Hartman's unique contribution to the monumental album, adding, 'I believe that all the artists involved raised the level of their games simply by their mutual commitment to quality and to making the best of every musical encounter. Thanks to Trane, 'compassion' was the name of the game. Therefore, a certain clear-eyed tenderness shone through.'

John Coltrane died in 1967, having continued to probe the far reaches of music he could create with his saxophone. Johnny Hartman lived until 1983. After making four more albums produced by Bob Thiele, he spent the '70s and early '80s performing mostly in lounges and supper clubs, recording for small independent labels. In 1981, he was nominated for a Grammy for 'Best Male Jazz Vocalist' for an album titled Once in Every Life. In 1995, director Clint Eastwood used seven tracks from that record, which had fallen out of print, on the soundtrack of his film Bridges of Madison County.

Tenderness, compassion and emotional transparency are, indeed, impressions one takes away from an encounter with John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, as well as admiration for its subdued lyricism and psychological acuity. Then there's the sheer pleasure one takes from close engagement with an object of multifaceted, inexhaustible beauty. Such engagement may occur once in a lifetime, or sometimes, if you're lucky, more often. If the 'object' is another human with whom one wants to strike a spark, or perhaps kindle a fire with and enjoy some warmth, it's very good to have Coltrane/Hartman at hand.

The 1950s, however, witnessed a sea change in popular music trends as the rougher vernaculars of rhythm and blues, Doo-wop, rockabilly and rock 'n' roll won over young audiences throughout America, and soon, the world. Sinatra, Eckstine, Tony Bennett, Nat King Cole and several others sustained careers based on the adult polish of their styles, but Ray Charles, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke subverted their dominance. As the big-band era ended, Hartman adapted by working with small combos in supper clubs and cabarets, while recording sporadically.

In 1959, he went to Europe 'to stay employed', as he put it years later. Intending to visit for two weeks, he stayed 11 months. He worked in England, Belgium and Germany, and appeared (according to Dr Gregg Akkerman's recently released biography, The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story)at least three times as a guest on British television. Eventually, he ran afoul of the musicians' union's staunchly protectionist rules; otherwise he might have opened a singing studio and perhaps hosted a TV programme of his own. Back in the States, he found that bookings were scarce for an urbane black man such as himself, who preferred refinement to rawness. A three- week tour of Japan, singing with drummer Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, was a high point of this period for Hartman. He was there when the call came from Bob Thiele, inviting him to collaborate with Coltrane.

'Johnny Hartman - a man that I had just stuck up in my mind somewhere - I just felt something about him,' Coltrane later said of his one-time-only partner. 'I liked his sound, I thought there was something there I had to hear.' In another interview, Coltrane offered another reason for his enthusiasm: 'He's a fine singer, and I wanted him to make a comeback.' The two had never worked together. They'd both been in Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra, but at different times.

Although Coltrane was so sure he wanted Hartman that he rejected Thiele's suggestions of other singers including Sarah Vaughan, Hartman had his doubts. 'I didn't know if John could play that kind of stuff I did,' he told writer Frank Kofsky a decade after the fact. 'So I was a little reluctant at first. Then John was working at Birdland, and he asked me to come down there, and after hearing him play ballads the way he did, man, I said, 'Hey, beautiful.' So that's how we got together.'

Jazz instrumentalists - perhaps tenor saxophonists, especially - are adept at portraying elegance, experience and sensitivity: ideal qualities in a lover. The best of them (for instance, Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Lester Young, Stan Getz and Dexter Gordon) acquire the ability to manipulate almost human-voice-like aspects from their horns, and control the dynamics of their breathing to evoke feeling over the course of decades of close listening. It's about delicate yet deliberate physical activity, and spontaneous, interactive self-expression. If such musicians have a strong-enough repertoire and perform thus, at the peak of their game, their music may live forever.

In contrast, most song stylists are irrevocably identified with their specific historical eras. When a certain mood is struck, one does not want one's romantic partner distracted by the voice of another man, or by her wondering if the album had been borrowed from your grandfather. Timelessness is what we're after when we want to take our own sweet time. A traditional pose, one that projects unquestioned credibility, is required. This is what was so right about the Coltrane/Hartman pairing. In 1963, Coltrane was 37, fairly young, yet even a cursory encounter with his music makes it clear he was a person containing profound depths. Hartman was 40, and not susceptible to passing fads. They may have held contrasting positions on an aesthetic continuum, but their gravitas was a match.

And so when, after a brief piano introduction provided by McCoy Tyner, Hartman intones, 'They say that... falling in love... is wonderful', with an air of faint disbelief overridden by ineffable yearning that the possibility be true; as Elvin Jones swishes wire whisks over his snare's drumhead, while Coltrane enters with a forthright statement of the same sentiment: we hear communion comparable to brothers bearing a single message.

The 1950s, however, witnessed a sea change in popular music trends as the rougher vernaculars of rhythm and blues, Doo-wop, rockabilly and rock 'n' roll won over young audiences throughout America, and soon, the world. Sinatra, Eckstine, Tony Bennett, Nat King Cole and several others sustained careers based on the adult polish of their styles, but Ray Charles, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke subverted their dominance. As the big-band era ended, Hartman adapted by working with small combos in supper clubs and cabarets, while recording sporadically.

In 1959, he went to Europe 'to stay employed', as he put it years later. Intending to visit for two weeks, he stayed 11 months. He worked in England, Belgium and Germany, and appeared (according to Dr Gregg Akkerman's recently released biography, The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story)at least three times as a guest on British television. Eventually, he ran afoul of the musicians' union's staunchly protectionist rules; otherwise he might have opened a singing studio and perhaps hosted a TV programme of his own. Back in the States, he found that bookings were scarce for an urbane black man such as himself, who preferred refinement to rawness. A three- week tour of Japan, singing with drummer Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, was a high point of this period for Hartman. He was there when the call came from Bob Thiele, inviting him to collaborate with Coltrane.

'Johnny Hartman - a man that I had just stuck up in my mind somewhere - I just felt something about him,' Coltrane later said of his one-time-only partner. 'I liked his sound, I thought there was something there I had to hear.' In another interview, Coltrane offered another reason for his enthusiasm: 'He's a fine singer, and I wanted him to make a comeback.' The two had never worked together. They'd both been in Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra, but at different times.

Although Coltrane was so sure he wanted Hartman that he rejected Thiele's suggestions of other singers including Sarah Vaughan, Hartman had his doubts. 'I didn't know if John could play that kind of stuff I did,' he told writer Frank Kofsky a decade after the fact. 'So I was a little reluctant at first. Then John was working at Birdland, and he asked me to come down there, and after hearing him play ballads the way he did, man, I said, 'Hey, beautiful.' So that's how we got together.'

Jazz instrumentalists - perhaps tenor saxophonists, especially - are adept at portraying elegance, experience and sensitivity: ideal qualities in a lover. The best of them (for instance, Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Lester Young, Stan Getz and Dexter Gordon) acquire the ability to manipulate almost human-voice-like aspects from their horns, and control the dynamics of their breathing to evoke feeling over the course of decades of close listening. It's about delicate yet deliberate physical activity, and spontaneous, interactive self-expression. If such musicians have a strong-enough repertoire and perform thus, at the peak of their game, their music may live forever.

In contrast, most song stylists are irrevocably identified with their specific historical eras. When a certain mood is struck, one does not want one's romantic partner distracted by the voice of another man, or by her wondering if the album had been borrowed from your grandfather. Timelessness is what we're after when we want to take our own sweet time. A traditional pose, one that projects unquestioned credibility, is required. This is what was so right about the Coltrane/Hartman pairing. In 1963, Coltrane was 37, fairly young, yet even a cursory encounter with his music makes it clear he was a person containing profound depths. Hartman was 40, and not susceptible to passing fads. They may have held contrasting positions on an aesthetic continuum, but their gravitas was a match.

And so when, after a brief piano introduction provided by McCoy Tyner, Hartman intones, 'They say that... falling in love... is wonderful', with an air of faint disbelief overridden by ineffable yearning that the possibility be true; as Elvin Jones swishes wire whisks over his snare's drumhead, while Coltrane enters with a forthright statement of the same sentiment: we hear communion comparable to brothers bearing a single message.

Hartman's tone, rising from a chamber near his heart to the tip of his tongue, bespeaks a longing to be joined in the test of a tender hypothesis. He sings as a man who is unsure such a thing as 'love' exists, but is more than willing to give it a try. The lightness with which he floats key words, and the way in which he lingers over such a neutral conjunction as 'and', beckon but do not demand response. Coltrane's chorus on sax rephrases, decorates and slightly expands upon the tune by Irving Berlin, but completely complements what Hartman has sung and returns the song to him for an even more hopeful iteration.

The second track on Coltrane/Hartman, 'Dedicated to You', written by Sammy Cahn, Saul Chaplin and Hy Zaret, is a pure offer of devotion, put forth with the same wistful, ready-to- be-rejected attitude as 'They Say It's Wonderful'. Hartman and Coltrane again express themselves with a limpid air of quietude. 'A lifetime would be just one heavenly day,' Hartman purrs to the subject of his passion. If that encomium doesn't earn him affection, his cause is lost.

But it isn't! 'My One and Only Love', which sees Coltrane first outlining the tune, is a simply beautiful testimony of consummation. There is no jumping for joy in either the saxophonist's or Hartman's declaration of ardour fulfilled. The manner of their gratitude is awed appreciation, not giddy overreaching. First recorded by Frank Sinatra in 1953, and many times since (including by Paul McCartney), the Coltrane/ Hartman version of 'My One and Only Love' is definitive: the core of the album, in fact.

Hartman's tone, rising from a chamber near his heart to the tip of his tongue, bespeaks a longing to be joined in the test of a tender hypothesis. He sings as a man who is unsure such a thing as 'love' exists, but is more than willing to give it a try. The lightness with which he floats key words, and the way in which he lingers over such a neutral conjunction as 'and', beckon but do not demand response. Coltrane's chorus on sax rephrases, decorates and slightly expands upon the tune by Irving Berlin, but completely complements what Hartman has sung and returns the song to him for an even more hopeful iteration.

The second track on Coltrane/Hartman, 'Dedicated to You', written by Sammy Cahn, Saul Chaplin and Hy Zaret, is a pure offer of devotion, put forth with the same wistful, ready-to- be-rejected attitude as 'They Say It's Wonderful'. Hartman and Coltrane again express themselves with a limpid air of quietude. 'A lifetime would be just one heavenly day,' Hartman purrs to the subject of his passion. If that encomium doesn't earn him affection, his cause is lost.

But it isn't! 'My One and Only Love', which sees Coltrane first outlining the tune, is a simply beautiful testimony of consummation. There is no jumping for joy in either the saxophonist's or Hartman's declaration of ardour fulfilled. The manner of their gratitude is awed appreciation, not giddy overreaching. First recorded by Frank Sinatra in 1953, and many times since (including by Paul McCartney), the Coltrane/ Hartman version of 'My One and Only Love' is definitive: the core of the album, in fact.

Which renders the next song, 'Lush Life', all the more tragic. Both the lyrics and the tune were written by Billy Strayhorn, whose sexual orientation may have increased his personal reticence during a repressed age, but did not hamper his long, creative alliance with Duke Ellington. A soliloquy full of vivid imagery and touching regret, the song had been recorded by Coltrane only two years earlier, and was added to the list of tunes considered for the album at the last minute. Coltrane and Hartman had heard Nat Cole's rendition on the car radio during the ride they shared on their way to record at Rudy Van Gelder's New Jersey studio, and had immediately agreed to try it. Hartman relates the sad story as if it's his own, concluding on a marvellously fragile note, which he holds steady as the musicians resolve in support.

'You Are Too Beautiful' follows up on the notion of Hartman, our protagonist, being left behind, although one might suspect that, since he's been so suavely in control up to this point, he's actually giving himself a way to disengage. Pianist Tyner shines on this track, with a fleetness in his solo that suggests escape more than self-sublimation. 'Autumn Serenade', the final track of Coltrane/Hartman, also depicts how a gentleman may think of love when it's over. With an exotic rhythm and Coltrane's most inquisitive effort, the track purports to recall a former splendour, but doesn't Hartman sound relieved, and free?

A popular legend, spread by producer Thiele and Coltrane's hagiographer Kofsky, among others, has it that the tracks on Coltrane/Hartman were, bar one, all captured on one take. Akkerman, in his Hartman bio, cites evidence to the contrary, which does not diminish the efficiency with which Coltrane, Hartman and the rest of the team created their tour de force. After checking the master takes, Coltrane returned to his microphone to add a phrase here and there. It makes no difference to the end result. Not one gesture on Coltrane/Hartman is out of place.

In 2005, commissioned by the Chicago Jazz Festival, singer Kurt Elling and saxophonist Joshua Redman attempted the daunting task of covering the Coltrane/Hartman material. The singer and his pianist Laurence Hobgood added strings to the original quartet arrangements, and included six more songs to flesh out the set. They performed the results subsequently on several occasions, including the Monterey Jazz Festival, and recorded it live at a concert for Jazz at Lincoln Center's American Songbook Series. It was released in 2009 as Dedicated to You: Kurt Elling Sings the Music of Coltrane and Hartman.

Which renders the next song, 'Lush Life', all the more tragic. Both the lyrics and the tune were written by Billy Strayhorn, whose sexual orientation may have increased his personal reticence during a repressed age, but did not hamper his long, creative alliance with Duke Ellington. A soliloquy full of vivid imagery and touching regret, the song had been recorded by Coltrane only two years earlier, and was added to the list of tunes considered for the album at the last minute. Coltrane and Hartman had heard Nat Cole's rendition on the car radio during the ride they shared on their way to record at Rudy Van Gelder's New Jersey studio, and had immediately agreed to try it. Hartman relates the sad story as if it's his own, concluding on a marvellously fragile note, which he holds steady as the musicians resolve in support.

'You Are Too Beautiful' follows up on the notion of Hartman, our protagonist, being left behind, although one might suspect that, since he's been so suavely in control up to this point, he's actually giving himself a way to disengage. Pianist Tyner shines on this track, with a fleetness in his solo that suggests escape more than self-sublimation. 'Autumn Serenade', the final track of Coltrane/Hartman, also depicts how a gentleman may think of love when it's over. With an exotic rhythm and Coltrane's most inquisitive effort, the track purports to recall a former splendour, but doesn't Hartman sound relieved, and free?

A popular legend, spread by producer Thiele and Coltrane's hagiographer Kofsky, among others, has it that the tracks on Coltrane/Hartman were, bar one, all captured on one take. Akkerman, in his Hartman bio, cites evidence to the contrary, which does not diminish the efficiency with which Coltrane, Hartman and the rest of the team created their tour de force. After checking the master takes, Coltrane returned to his microphone to add a phrase here and there. It makes no difference to the end result. Not one gesture on Coltrane/Hartman is out of place.

In 2005, commissioned by the Chicago Jazz Festival, singer Kurt Elling and saxophonist Joshua Redman attempted the daunting task of covering the Coltrane/Hartman material. The singer and his pianist Laurence Hobgood added strings to the original quartet arrangements, and included six more songs to flesh out the set. They performed the results subsequently on several occasions, including the Monterey Jazz Festival, and recorded it live at a concert for Jazz at Lincoln Center's American Songbook Series. It was released in 2009 as Dedicated to You: Kurt Elling Sings the Music of Coltrane and Hartman.

Asked how he approached such etched-in-stone material, Elling told The Rake, 'In an intuitive way, largely ignoring the weight of history or of perceived expectations.' He identified 'a golden voice and emotional transparency' as Hartman's unique contribution to the monumental album, adding, 'I believe that all the artists involved raised the level of their games simply by their mutual commitment to quality and to making the best of every musical encounter. Thanks to Trane, 'compassion' was the name of the game. Therefore, a certain clear-eyed tenderness shone through.'

John Coltrane died in 1967, having continued to probe the far reaches of music he could create with his saxophone. Johnny Hartman lived until 1983. After making four more albums produced by Bob Thiele, he spent the '70s and early '80s performing mostly in lounges and supper clubs, recording for small independent labels. In 1981, he was nominated for a Grammy for 'Best Male Jazz Vocalist' for an album titled Once in Every Life. In 1995, director Clint Eastwood used seven tracks from that record, which had fallen out of print, on the soundtrack of his film Bridges of Madison County.

Tenderness, compassion and emotional transparency are, indeed, impressions one takes away from an encounter with John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, as well as admiration for its subdued lyricism and psychological acuity. Then there's the sheer pleasure one takes from close engagement with an object of multifaceted, inexhaustible beauty. Such engagement may occur once in a lifetime, or sometimes, if you're lucky, more often. If the 'object' is another human with whom one wants to strike a spark, or perhaps kindle a fire with and enjoy some warmth, it's very good to have Coltrane/Hartman at hand.

Asked how he approached such etched-in-stone material, Elling told The Rake, 'In an intuitive way, largely ignoring the weight of history or of perceived expectations.' He identified 'a golden voice and emotional transparency' as Hartman's unique contribution to the monumental album, adding, 'I believe that all the artists involved raised the level of their games simply by their mutual commitment to quality and to making the best of every musical encounter. Thanks to Trane, 'compassion' was the name of the game. Therefore, a certain clear-eyed tenderness shone through.'

John Coltrane died in 1967, having continued to probe the far reaches of music he could create with his saxophone. Johnny Hartman lived until 1983. After making four more albums produced by Bob Thiele, he spent the '70s and early '80s performing mostly in lounges and supper clubs, recording for small independent labels. In 1981, he was nominated for a Grammy for 'Best Male Jazz Vocalist' for an album titled Once in Every Life. In 1995, director Clint Eastwood used seven tracks from that record, which had fallen out of print, on the soundtrack of his film Bridges of Madison County.

Tenderness, compassion and emotional transparency are, indeed, impressions one takes away from an encounter with John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, as well as admiration for its subdued lyricism and psychological acuity. Then there's the sheer pleasure one takes from close engagement with an object of multifaceted, inexhaustible beauty. Such engagement may occur once in a lifetime, or sometimes, if you're lucky, more often. If the 'object' is another human with whom one wants to strike a spark, or perhaps kindle a fire with and enjoy some warmth, it's very good to have Coltrane/Hartman at hand.