Stop Making Sense: David Byrne

One of American music's great chameleons, the former Talking Head is a multi-instrumentalist known for his distinctive voice and surrealist fashion sense.

David Byrne, whose new documentary Contemporary Colour comes out in the US this week, is a professor of worldly innocence, the ringmaster of music as democratic circus, a magpie feathered like a cockatoo. A rare winner of an Oscar, a Grammy and a Golden Globe, the Scottish-born singer is a multi-instrumentalist known for his yearningly high voice, surrealist fashion sense, tufty white hair and forays into film, photography, opera, architecture, fiction and non-fiction. As influential as he is influenced, his band Talking Heads have inspired the likes of REM, Vampire Weekend and Radiohead, who named themselves after one of their songs.

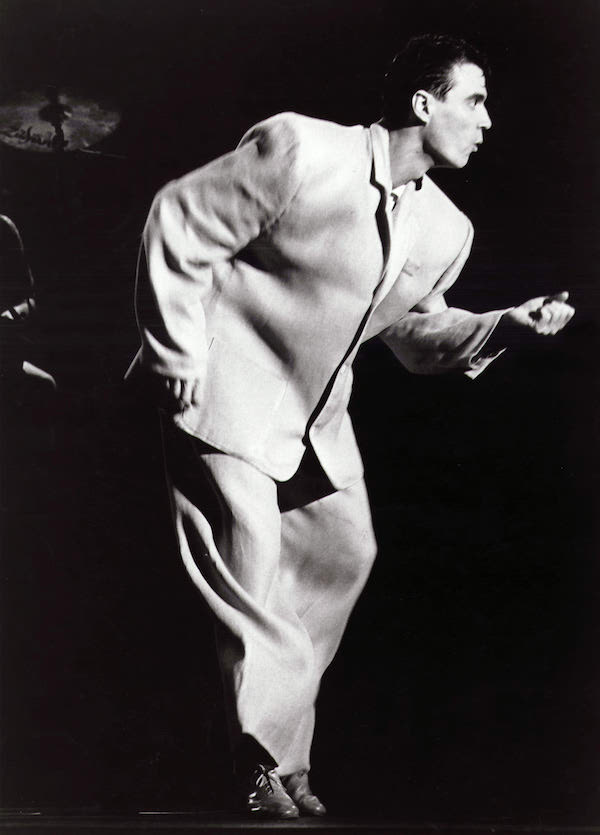

A gauche student who poured his shyness into pop, he formed Talking Heads in 1975 with two friends from his Rhode Island art school. Against the glam excess of T-Rex and Queen, Byrne felt the most subversive look for a new band was total normality, so he bought a $50 office suit to perform in. Their post-punk art-pop imagery would expand over their eight studio albums and Byrne, like Morrissey, had a particularly good ear for song titles. Their debut Talking Heads 77 harmonised bookish introspection (‘Tentative Decisions’) with mordant scandal (‘Psycho Killer’). Sophomore album More Songs About Buildings and Food covered Al Green’s ‘Take Me To The River’, smooth soul dressed in jerky postmodern businesswear.

From here, the band sounded fuller and more porous. Fear of Music compressed philosophical sketches into Warholian one-word titles (‘Paper’, ‘Cities’, ‘Air’, ‘Heaven’, ‘Drugs’). They dabbled in funky futurism (‘Houses In Motion’), electro melancholy (‘This Must Be The Place’), retro pop (‘And She Was’, the sunnily apocalyptic (‘Road To Nowhere’) and domestic surrealism (‘Mommy Daddy You and I’) before they broke up in 1991.

The split was an opportunity for Byrne to broaden his horizons even further, most fruitfully with Brian Eno, the ambient pioneer behind Roxy Music and David Bowie. Their two albums together, My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts and Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, are Byrne’s finest work outside Talking Heads, gorgeous hybrids of Byrne’s jangling rhythms, Eno’s Kraftwerkian minimalism and combined dreamlike lyrics. Like Eno, Byrne is a prolific solo artist, promiscuous collaborator (flings include Arcade Fire, Paul Simon and St Vincent), world music self-infuser (merengue, son cubano, samba, mambo, country, African popular music) and producer in his own right (his own label Luaka Bop champions genres from Brazilian pop to Japanese folk).

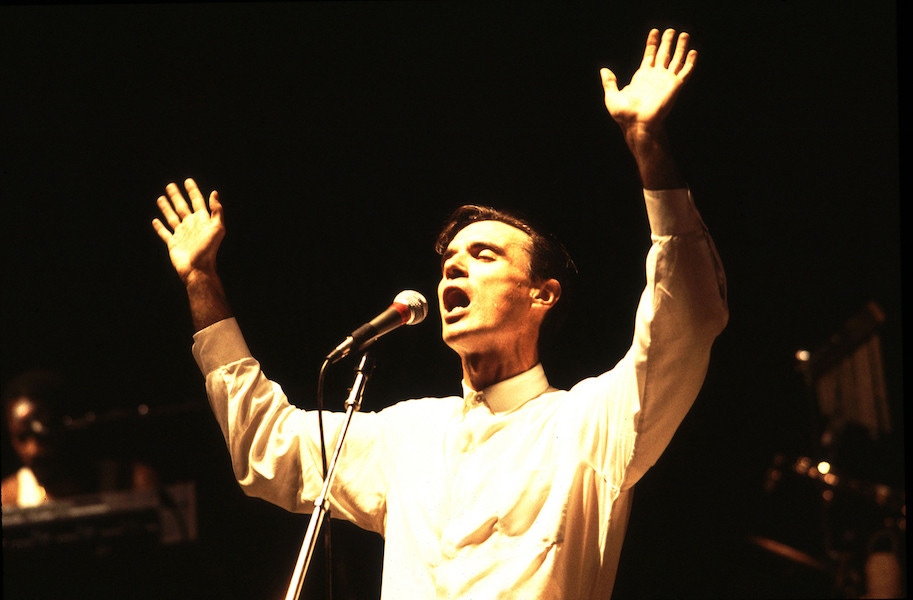

What frames the music is a sharp sense of his own iconography, burnished by two concert films: Jonathan Demme’s Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense, which immortalised his giant suit aesthetic, and Eno tour hymnal Rise, Ride, Roar. He has curated vivid music videos, left clues in album cover art, composed film scores for Italian auteurs (from Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor to Paolo Sorrentino’s This Must Be The Place) and even written a disco opera about Imelda Marcos.

Byrne is one of those heroic, slightly exhausting men who seems to be interested in everything, not least buildings. In his brilliant TED Talk “How architecture helped music evolve”, he traces how music has adapted over the centuries to its environment: Mozart to frilly Viennese drawing rooms, Wagner to the shouty La Scala, textured Sinatra-style croons to the quieter microphone-rigged Carnegie Hall, anthemic medium-speed ballads (like U2) for arenas and sport stadia. Even birdcalls, he says, are more high pitched and repetitive where the foliage is denser. No wonder he can calibrate the space around himself so well. In 2008, he turned the Battery Maritime Museum, a 99-year-old ferry terminal in Manhattan, into a playable musical instrument, and recently did the same to London’s Roundhouse.

For all his erudition, he preserves a sense of humour and style. An obsessive cyclist, he has designed bike racks for New York’s Department of Transportation (a dollar sign for Wall Street; a stiletto shoe for the Bergdorf Goodman department store). Typical daywear can include a Sherlock Holmes deerstalker and spikeless golf shoes. He has a soft spot for semi-absurd epigrams (“To shake your rump is to be environmentally aware”), but he’s also rigorously connected to the financial implications of how music is consumed now. An opponent of Spotify, he fears the Internet “will suck all creative content out of the world”.

Like fellow Davids Lynch and Bowie, Byrne has enriched and variegated his cross-cultural relevance ceaselessly since his twenties, permanently ahead of the bell curve, cerebral and drawn to niches but no dusty academic. His playfulness, like the backwards pagination of his book How Music Works, doesn’t always have to be parsed or explained. Much better, like the birds, to adapt and sing and that the joy is still there. Rise, ride, roar. Burn down the house. Stay hungry. Pull up the roots. Stop making sense.