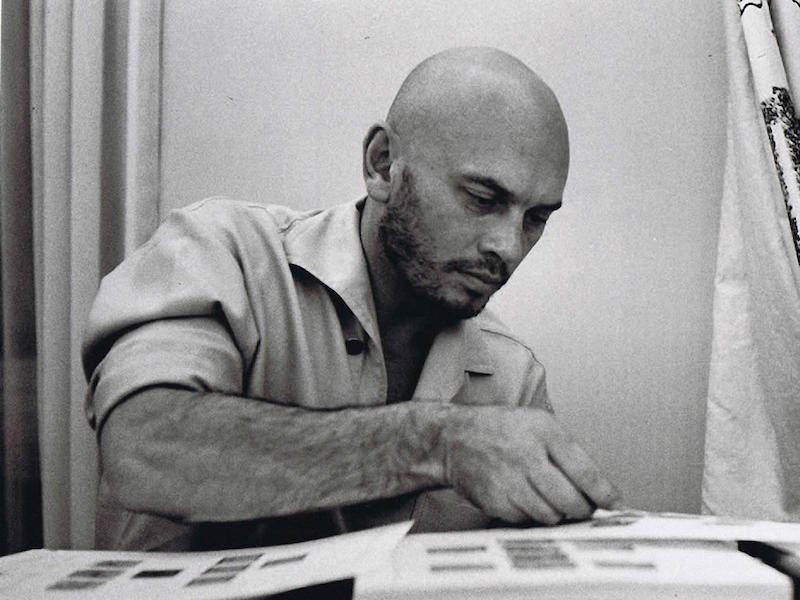

Tender Was The Fight: F. Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald

Copious amounts of moonshine, acute professional envy and severe mental illness doesn’t sound like a recipe for romantic felicity: but there must have been more than acrimony and strife, in the troubled union of jazz-age literary darlings F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

When F. Scott Fitzgerald anointed his wife “the first American flapper”, he was referring entirely to the most superficial layer of her personality. During her formative years, Zelda’s contagious vivacity and eccentric fizz had been the talk of the southern aristocracy into which she was born - she was the daughter of a well-heeled Alabama Supreme Court justice, and the cartwheels she would perform on the steps of her father’s workplace in her late teens were typical of her attention-seeking escapades - while her compelling beauty made her artists’ muse du jour.

But to say that the socialite-novelist born Zelda Sayre in 1900, the youngest of six children, was troubled would be a severe understatement. Zelda’s voracious appetite for attention cared not for any distinctions between admiration and admonishment, and while still a teenager, each cigarette served as a lighter for the next one to be wedged into the lengthy receptacle through which she chuffed them, and gin-ravaged evenings were plentiful. Signs of acute disturbance surfaced in the late 1920s, and a 15-month stay at the Prangins Clinic in Switzerland was followed by a relapse, then a nine-week stay at an upmarket New York hospital at which spousal visits were initially discouraged.

This was barely a decade into a relationship that had been troubled from the outset. The Gatsby author had met the object of his turbulent affections when she was 18, four years his junior, in a country club near Montgomery, Alabama, where he was serving as an infantry lieutenant. He proposed to her as soon as he was discharged from the army, but a Princeton drop-out and aspiring writer was no suitable suitor for someone of Zelda’s social standing at the time, and Scott going off to work as a copywriter for a New York advertising agency, his accommodation a single-room hovel in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights, hardly helped matters. Few onlookers were surprised when she gave back the ring, prompting a three-week bender in Scott before he decided to hole up at his parents’ house and pen the novel that would win back his sweetheart.

"Zelda’s voracious appetite for attention cared not for any distinctions between admiration and admonishment, and while still a teenager, each cigarette served as a lighter for the next one..."The book in question, This Side of Paradise, drew transparently on the couple’s own romance - young Princeton student quits university, joins up, and is seduced then and left devastated by a woman with an uncannily resemblance to Zelda Sayre – and was a hit with both publishers and the boisterous belle to whom it was effectively a fictional love letter. The two exchanged wedding vows at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral a week after its publication. They transferred to Paris, but an ostensibly idyllic life hobnobbing with Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein ensued was marred by personal issues – Zelda’s probably platonic but ostensibly romantic entanglement on the Riviera with a French pilot, for example, and her own suspicions that her husband was dallying with Ernest Hemingway (a man she once referred to as “a pansy with hair on his chest”). It was professional jealousies, though, that put the even more untenable strain on them. Scott once described his wife’s prose as “third rate”; she countered that he picked up her “crumbs” as material for his. Ironically, given the premise of his debut novel, he forbade her to use their rocky relationship as fictional raw material, then squirrelled away on Tender is the Night – his French Riviera-set bout of artistic tooth-extraction dealing with nuptial disintegration – while she was hospitalised for schizophrenia in Baltimore. Scott also apparently pilfered material from Zelda’s diaries and letters.

Scott was reportedly incandescent with rage when his wife’s novel, Save Me the Waltz, drew from autobiographical source material he had hoped to purloin from reality himself. It’s reported that, when Scott would go on the wagon in order to devote sober attention to his writing, Zelda would embark on a bender that she knew he wouldn’t be able to resist joining in. “I lost my capacity for hope on the little roads that led to Zelda's sanatorium,” Scott later wrote.

The pair’s story has no fairy tale conclusion: Scott died at 44 from a heart attack, while his wife would perish eight years later when the hospital room in which she was awaiting electrotherapy caught fire. But are we talking, here, about a union of unadulterated strife? Could all the furniture of their existence together – the hapless spending, glitzy hotels, smoke-filled speakeasies, intercontinental voyages, sartorial exuberance and decadent parties at their seven-bedroom waterfront villa in Cap d'Antibes – really just have been nothing more than worthless accoutrements to a life of bitter marital acrimony?

"Scott once described his wife’s prose as “third rate”; she countered that he picked up her 'crumbs' as material for his."“Zelda always seemed like the tragic heroine of her own and other people's novels,” biographer Sally Cline once told the UK’s Observer newspaper. “She was a woman who adored and hated her husband, who adored and oppressed and victimised her. Her melodramatic life was in real terms the stuff of fiction.” Therese Anne Fowler, author of Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald, goes further, suggesting their simultaneous repulsion/attraction stimulated them, energising them creatively: “They were two sides of one coin,” she says. “It's difficult to imagine that we would be talking about either one of them had they not been a pair.” But it’s an observation of a broader existential nature, one from a figure entirely detached from the protagonists – American writer, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel – that best sums up this most enigmatic of relationships: “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it's indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference.”