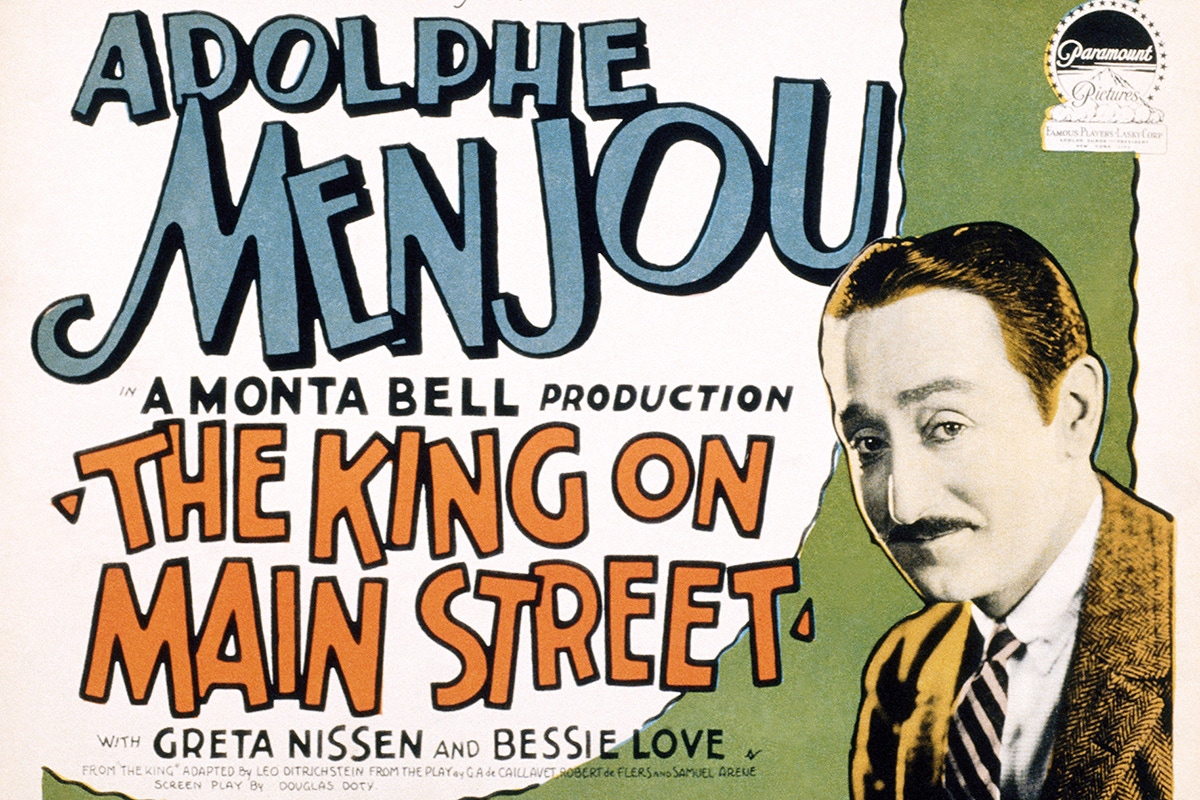

The Duke of Beverly Hills: Adolphe Menjou

Adolphe Menjou was one of the few Hollywood stars to make a successful transition from silent movies to talkies. Clark Gable called him a financial genius, an intellectual and a raconteur, but he was most renowned for his unimpeachable style, a dapper sensibility that regularly made him the best-dressed man in America.

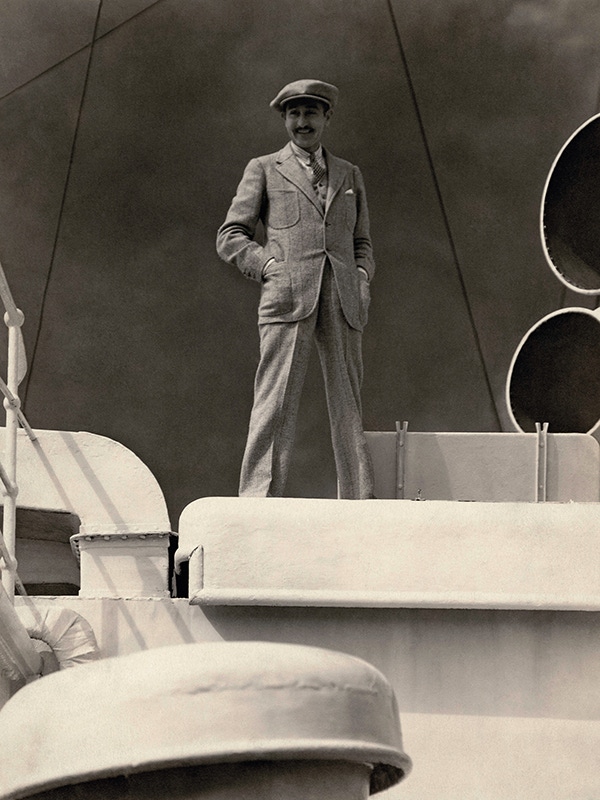

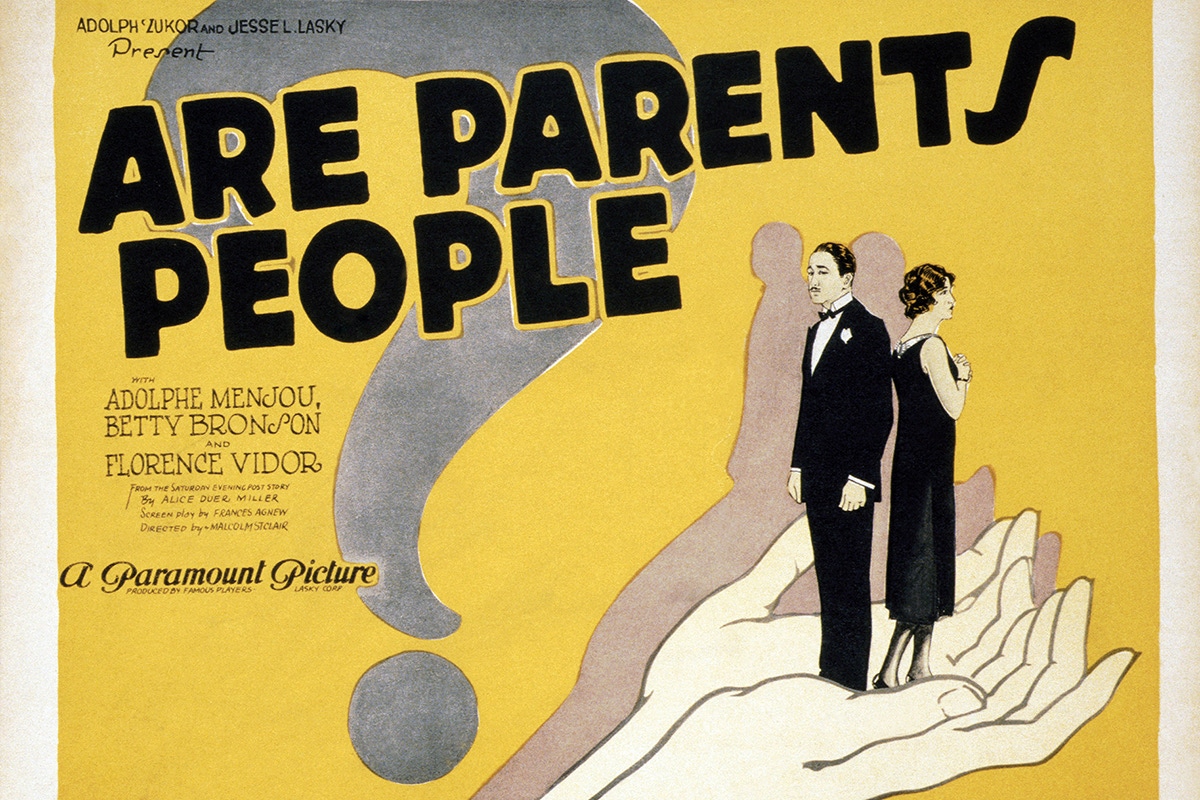

For some actors, the key to a role starts with the voice. For others, it’s the walk. For Adolphe Menjou, who made his debonair mark during the waning days of silent cinema in the 1920s, it was all about an impeccably waxed moustache allied to an immaculate dress suit. In an era when character was telegraphed, kabuki-like, through appearance and gesture, the moustache, he wrote, “was the mark of a villain — a rich city slicker or a foreign nobleman”, and the Pittsburgh-born, French/Irish-descended Menjou ran the roguish gamut, playing “Russian aristocrats, Italian Marcheses, and suave but unsavoury blackmailers”. He revelled in his status as the go-to guy for blithe decadence — he even played Lucifer in D.W. Griffith’s 1926 epic The Sorrows of Satan — and he avidly embraced the repeated accolade of best-dressed man in America.

In his introduction to Menjou’s autobiography, It Took Nine Tailors (which gets The Rake’s vote for best book title ever), his friend Clark Gable eulogises his talents as a financial genius (he played the stock market with some success), an intellectual (he could “converse on Balkan politics of the 1910s”, among other recondite topics), a raconteur, and, getting to the nub of the matter, a fashion critic: “He can tear a lapel apart with the most scathing and contemptuous adjectives I have ever heard, and he can pass a critical eye over your pants in a manner that makes you feel you’ve come to dinner wearing baggy overalls.”

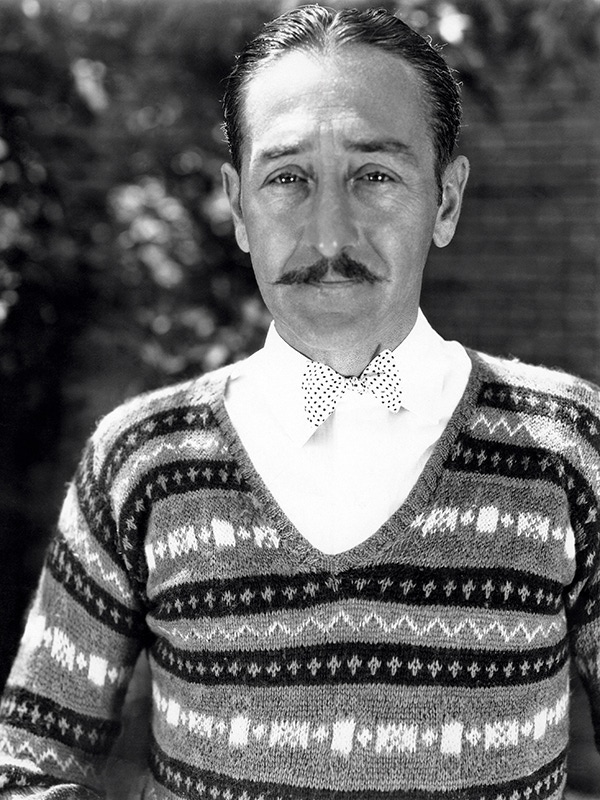

"It was all about an impeccably waxed moustache allied to an immaculate dress suit."Menjou got his dapper sensibility and censorious eye from his father, a French-born hotelier and restaurateur who had a resplendent moustache of his own, and, wrote his son admiringly, “was a stickler when it came to clothes”. Young Adolphe was expected to enter the hospitality business himself, but was hopelessly seduced by the impromptu movie shows his father set up on the top floor of his Cleveland restaurant. He began acting in Cornell University’s dramatic productions, when he was ostensibly there to study engineering; by 1913, his trademark facial hair firmly established, he’d landed a role as a circus ringmaster in a two-reeler called Man of the World, for which he was paid $15. “I found movie acting amazingly simple,” he wrote, in typically breezy style. “There were no lines to learn, and few, if any, rehearsals. When I realised they had me pegged as a foreign-nobleman type, I began to live the part. I bought a pair of white spats, an ascot tie and a walking stick, and I tried to look as decadent as possible. It paid off, too: I did so many of those parts that my nickname in Brooklyn was The Duke.” After a year’s service in the first world war, during which he taught his company’s cooks “how to make the perfect potau-feu”, Menjou lit out for Hollywood, where he was soon making the acquaintance of the likes of Gable and Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle (who lent him his Pierce-Arrow for his studio commutes) in high-stakes poker games. He played Louis XIII in Douglas Fairbanks’s The Three Musketeers in 1921, and was cast alongside Valentino in The Sheik that same year. Menjou had the perfect face for a silent movie villain: it tended to veer between a complacent smirk and a malevolent sneer, the points of his moustache flicking mischievously like inverted commas. “I was such a deep-dyed scoundrel that the kids in the audience would start hissing as soon as I appeared on screen,” he wrote. He was invariably killed off in the last reel to sate the punters’ panto bloodlust.

Inevitably, Menjou attracted the attention of Hollywood’s most significant players. David O. Selznick called him in for an audition with the immortal words, “We want you because you wear clothes better than anybody in Hollywood”. But Menjou was more attracted to the idea of playing Pierre Revel, a Gallic boulevardier and bon vivant, in Charlie Chaplin’s 1923 movie A Woman of Paris, so much so that he lunched in the restaurants Chaplin frequented, hoping to be noticed “dressed in white tie and tails, formal morning attire, white flannels, hunting tweeds with an Alpine hat… anything that a wealthy Parisian might wear.” Chaplin, doubtless floored by such sartorial commitment, caved in, but if Menjou was impressed by his director’s punctiliousness during the eight-month shoot, he was less taken with his appearance. “Chaplin’s wardrobe was deplorable,” he wrote. “He had no style in his clothes or the way he wore them. I inquired who his tailor was — to my horror, he confessed he hated tailors, and had never had a tailored suit in his life.”

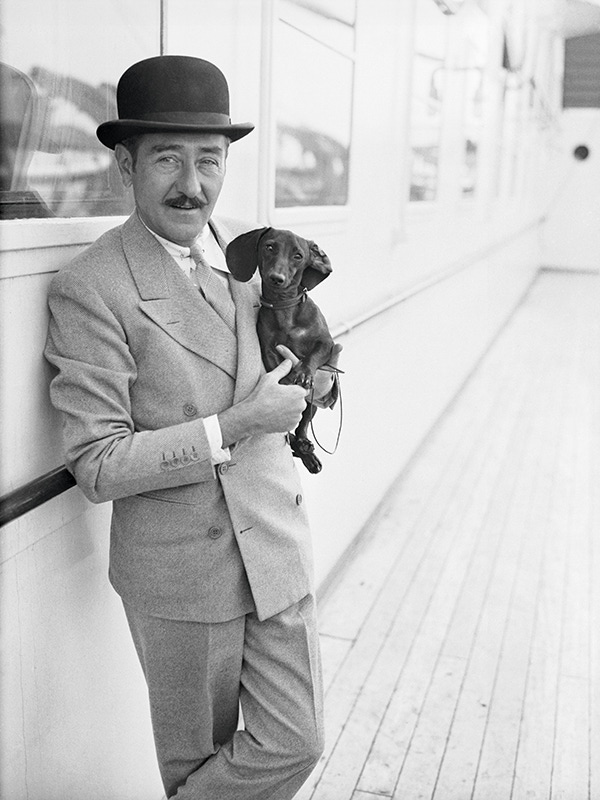

There could be few graver faux-pas in Menjou’s book. For A Woman of Paris, he had a $250 opera cape made up (“that I have never worn”), and a grey cutaway “for a racetrack scene that was never shot”. (Years later, he had a racetrack scene written into a movie “just so I could wear it”.) In It Takes Nine Tailors, he proudly lists the actually-closer-to-13 bespoke houses he frequented, including Anderson & Sheppard, Caraceni, Pope & Bradley, Henry Poole & Co, Sandon (“for breeches and riding clothes”), Knize in Berlin, and P&J Haggart in Scotland (“for tweeds — the Earl of Portarlington told me about them”). His mainstay, however, was a tailor named Eddie Schmidt, based in downtown Los Angeles; Menjou was so impressed by Schmidt’s outfit on his initial visit — “white carnation, white spats” — that he ordered six suits on the spot, “$750-worth — on tick, of course”. He further claims that he and Schmidt introduced some subtle innovations to men’s tailoring: “We took the buckram out of jacket linings so they draped with fullness over the chest, and we spread the top buttons on double-breasted jackets so the shoulder line was broadened.”

"Menjou’s attention to detail went along with his burgeoning reputation as Hollywood’s sprucest."Menjou’s attention to detail went along with his burgeoning reputation as Hollywood’s sprucest. He sued a “cheap haberdasher” who had the temerity to market “Adolphe Menjou” ready-tied bow ties, and his biggest challenge in 1934’s Little Miss Marker wasn’t facing off against co-star Shirley Temple, but the “thirty-five-dollar fiddle and flute” in blue serge he had to wear as a down-at-heel bookie (the results were bittersweet: Menjou got great notices, but was left off the Merchant Tailors’ Association best-dressed list for the first time). More profound changes were afoot, however. The end of the twenties brought not only the Wall Street crash but also the coming of the talkies; but if, as Menjou wrote, “the slick, sophisticated, dress-suited characters I had been playing were out of step with the Depression”, he made the transition to sound much more smoothly than the majority of his peers. Fans were pleasantly disarmed to hear a Pennsylvania rasp emanating from that epicurean face, rather than the silken mittel-European tones they expected, and Menjou took full advantage with his bestknown role, that of the wisecracking newspaper editor Walter Burns in 1931’s The Front Page, which earned him an Oscar nomination for best actor. Menjou went on working into the 1950s: some pictures, he admitted, were “very large cuts of Gorgonzola”, but he impressed as a pitiless French general in Stanley Kubrick’s 1957 anti-war masterpiece Paths of Glory. By then, however, Menjou’s reputation had been somewhat tarnished by his enthusiastic backing of the House Un-American Activities Committee, set up to root out communists in the entertainment industry, before whom he appeared as a friendly — and fiery — witness, denunciating and naming names. His politics might have been unpalatable, but his way with a tailcoat and boutonnière remains forever unimpeachable. Menjou died in 1963 after contracting hepatitis; he was, of course, buried in one of his flawless suits, his collar starched, his moustache buffed, the embodiment of old-school urbanity to the end. Originally published in Issue 49. Subscribe here for more.