The Importance of Being Rupert

An unpredictable magnet for scandal and far too intelligent for his own good, Rupert Everett's career has always crackled with the energy of a storm about to break.

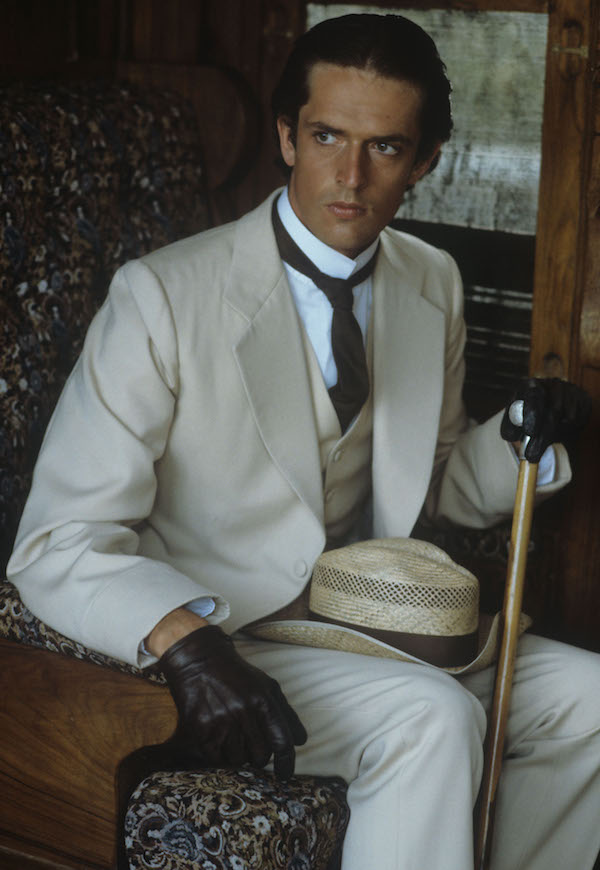

Rupert Everett may be the most rakish actor alive. He snarls with anti-macho beauty, languid, hunched and hawk-like. Amongst his coterie of ancestors, Lord Byron’s high-low hedonism and Noel Coward’s smoke-and-silk elegance shoulder the sedan chair of Oscar Wilde, whom Everett has played several times and will play again this year. To paraphrase Jim Morrison, Wilde’s cemetery neighbour at Père Lachaise, Everett is a cerebral erection, all sensation sucked up into the skull: vital, melancholy, elegiac, savage, perspicacious, cinema as chaste fantasy, life as impossible depravity.

Fed Catholicism from an early age “like a foie gras goose”, Everett ran away from the Benedictine monks at public school Ampleforth aged 16 to work as a prostitute to fund his acting ambitions. Dismissed from drama school for insubordination, he soon dazzled aged 21 in Another Country as a gay public schoolboy opposite a young Colin Firth. Then, after playing enigmatic tourists in literary adaptations (Ian McEwan’s The Comfort of Strangers; Gabriel García Márquez’ Chronicle of a Death Foretold), he hit superstardom in My Best Friend’s Wedding, a film he steals as effortlessly as his character George upstages Cameron Diaz’s wedding rehearsal lunch. It is a glorious performance, puckish, joy-drenched and radiant with charisma. (He has since said he loathes heterosexual weddings and found Julia Roberts “as skittish as a racehorse”.)

Shakespeare and Wilde dominate his CV since (An Ideal Husband, king-of-the-fairies Oberon in A Midsummer’s Night Dream, The Importance Of Being Earnest), but he has been criminally underused as a leading man, possibly because of his role in Madonna’s critically detested The Next Best Thing, possibly because he is openly gay (he once sold an idea to a studio for a homosexual James Bond). It is cinema’s loss, as he has flourished at the vanguard of TV (Black Mirror) and theatre (as an aging, Olivier-nominated Oscar Wilde in Sir David Hare’s The Judas Kiss).

Like Oliver Reed, glimpses of Everett’s private life only intensify what might have been on screen. Lauren Bacall once called him “the wickedest woman in Paris”, where he befriended Delphine, the Brazilian transsexual ruler of the Bois de Boulogne (according to Everett, “hers was the most famous erection”). Two volumes of hilarious, soulful, gorgeously written memoirs reveal affairs with Susan Sarandon, Paula Yates and Ian McKellen, whom he stalked until Sir Ian gave in and shagged him. (Everett defines his own sexuality as “adventurous: I basically wanted to try everything”). He became Madonna’s best friend and sang backing vocals on her version of ‘American Pie’, until he outed her as a “whiny old barmaid” who played with her boyfriend’s penis in public. The Telegraph notes that he hung out at Princess Diana’s flat, flirted with Nureyev and Yves Saint Laurent, and Andy Warhol wrote “I love you” on his face with Bianca Jagger’s lipstick.

Everett’s turn-of-phrase, as deft and evocative as a Romantic poet’s, creates a bloodstream of images. He describes Richard Harris as a “stone jouster knight who slipped off his tomb”. A Cambodian forest is “shredded with moonbeams”. New York is a “gigantic fortress in a blur of exhaust.” Angela Lansbury has the “eyes of an owl and the tenacity of a mountain goat”.

By his own admission, Everett could be extremely difficult, ready to undam the “sheer tsunami of divadom” in a heartbeat. Old friend Simon Callow says he “did behave so very badly”. Famously outspoken in interviews, he has called soldiers wimps, the USA “blobby and whiny”, Starbucks a “cancer” and Alistair Campbell’s nose “made for aggression or at least cunnilingus”. He is a staunch Monarchist and a control freak, who only lets photographers photograph him from above and eats the same lunch at the same Italian restaurant every day (he ate out for every meal between the ages of 22 and 50). To preserve his looks, he has his own blood injected into his face every four months, an extraordinarily gothic life-art mix of Dorian Gray and Frankenstein. But he also laughs at himself as a “manic beanpole show-off” who is not “built for excessive wealth (too tall)”.

Everett turns 58 in May - plenty of time yet for more cinema-society sass. His recent career choices veer towards the autobiographical: a documentary on Byron’s love life, the creatively unfulfilled Salieri in Amadeus and (out later this year) his latest incarnation of Oscar Wilde in The Happy Prince, a film written and directed by Everett in which he’s cast himself as the dying dandy opposite Another Country co-star Colin Firth – an apt reunion. If Firth is the academy-approved Jekyll of upper-class English desire, Everett is its wild, enigmatic Hyde. To quote Wilde’s De Profundis, which Everett read in public at Oscar’s Parisian tomb in 2011: “The final mystery is oneself… Who can calculate the orbit of his own soul?” Rupert Everett comes pretty damn close.