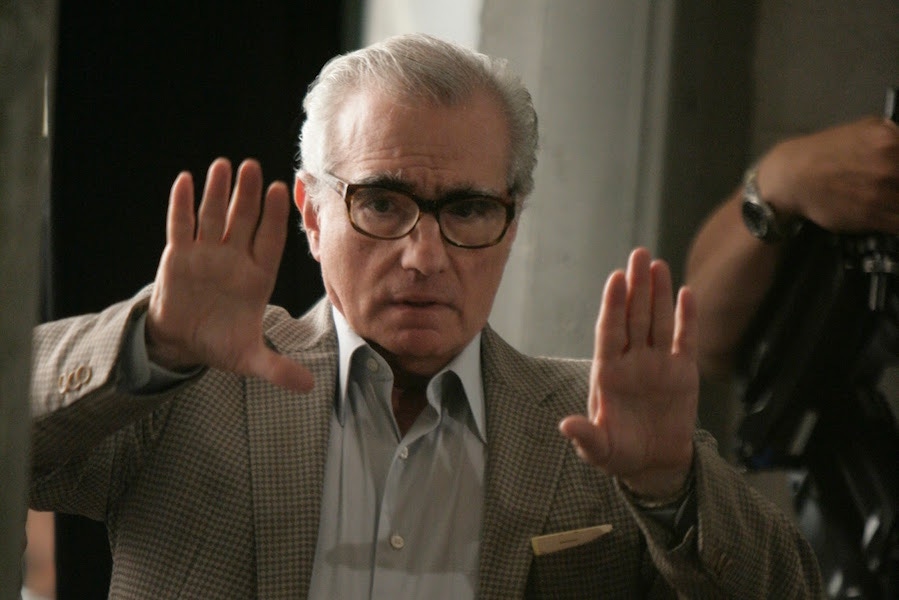

The Last Temptation of Martin Scorsese

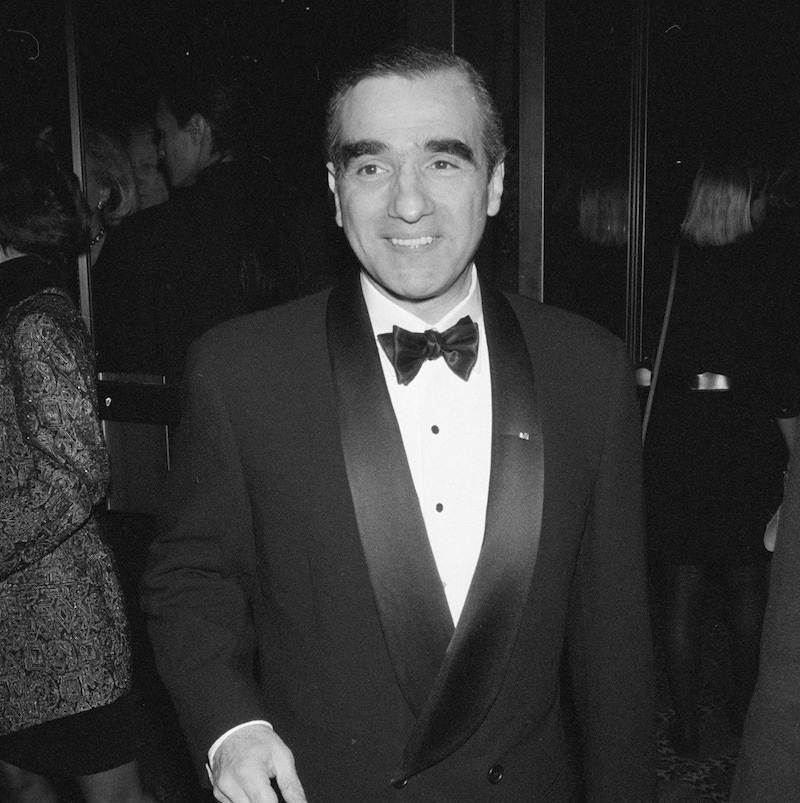

With the release of Silence later this year, Ed Cripps takes a look at how Martin Scorsese has carved such a successful niche for himself in cinema.

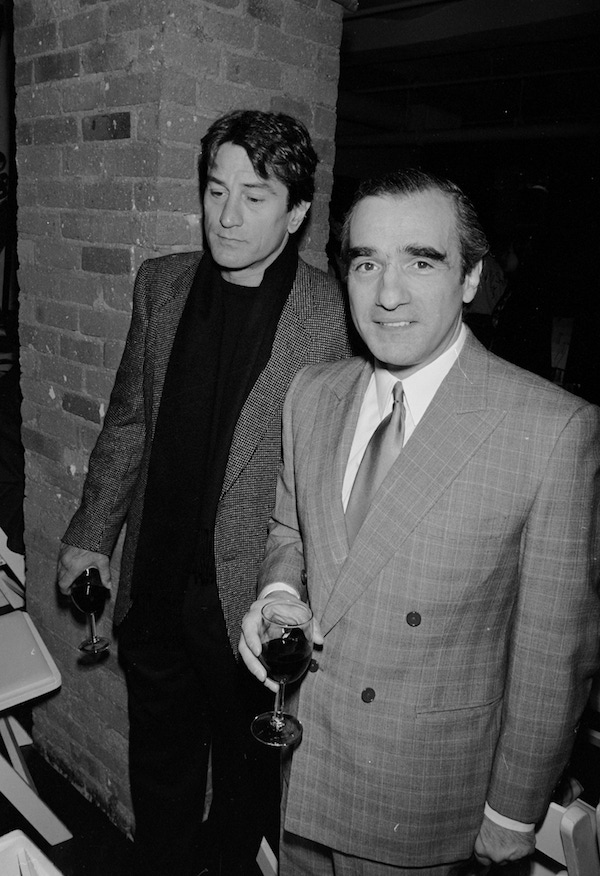

Martin Scorsese is the dark archangel of American cinema, tortured, resurrected and now universally revered. Washing his lens in foreign new waves, he has found a kinetic poetry in the pain of urban life and the tensions between family, crime, Catholicism, Italy, America, guilt, redemption, fantasy and reality. There are two main muses: Robert De Niro, with whom he has made eight films, is a telepathic double, skittish and violently vulnerable. Leonardo DiCaprio, with whom he has made five, has a more polished despair. De Niro is the man-as-child, DiCaprio the child-as-man, a father and son to Scorsese’s unholy spirit. Neither appear in Scorsese’s new film Silence, which the director has been trying to make since the eighties and will finally be released later this year. Seventeenth-century Jesuit missionaries in Japan may seem a far cry from New York gangsters, but it’s quintessential Scorsese and a result of almost religious perseverance, range and reinvention - the perfect start to his seventy-fifth year.

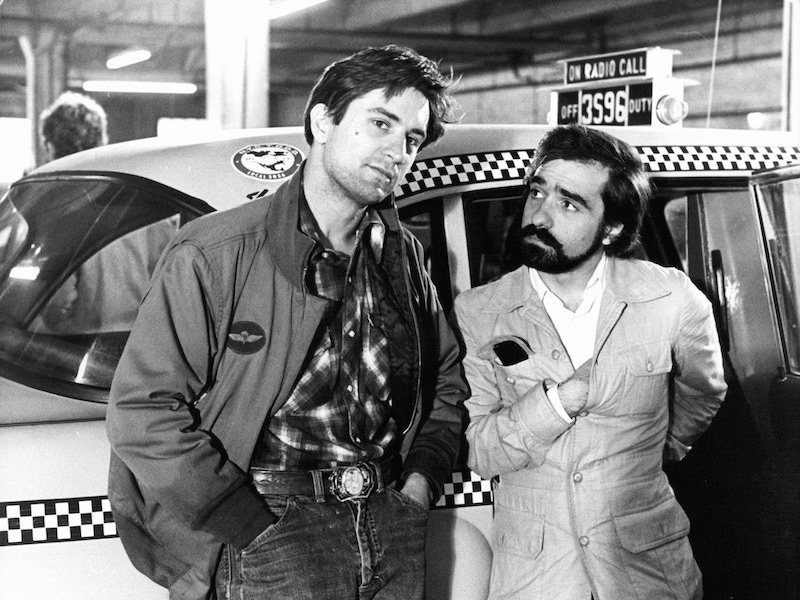

Mean Streets, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull form another holy trinity within Scorsese’s career, artful, bloody, feverishly moral grand canvases that electrified a newer Hollywood into life. Pauline Kael praised Mean Streets for “a thicker-textured rot and violence than we have ever had in any American movie, and a riper slice of evil”. Taxi Driver starts with the nervy sweetness of a romcom and becomes a post-Vietnam malarial nightmare, with Travis Bickle’s car a metaphor for urban loneliness and voyeurism (the cab as camera, perhaps). Raging Bull is Scorsese’s masterpiece, a headily black-and-white, sprawlingly taut, gorgeously edited torrent of anger, envy and anti-vanity. So addicted to cocaine at the time that he worried it might be his last film, Scorsese has described it as “a Kamikaze of film-making”.

This is gory Old Testament Scorsese and, for all the vim of later crime films (Cape Fear, Goodfellas, Casino, Gangs of New York, even The Departed), the quieter, New Testament Scorsese beguiles even more. The King of Comedy is just extraordinary: Scorsese’s first film after Raging Bull and unfairly maligned by comparison on its release, it is a clairvoyantly funny, gloriously bleak study of ambition, disappointment and fame from the deluded perspective of stand-up Rupert Pupkin (Scorsese has said it's his favourite De Niro performance). In a kindred key, The Aviator captures Leonardo DiCaprio at his subtlest and a far more nuanced, endearing American-dream-gone-sour than, say, The Wolf of Wall Street. There’s also The Age of Innocence, an elegantly unusual Edith Wharton adaptation with Daniel Day-Lewis and a homage of sorts to Visconti's The Leopard.

He has also mixed faith and film with music and literature. Only he, in The Last Temptation of Christ, could cast David Bowie as Pontius Pilate. The Last Waltz, his superb documentary about The Band's final gig with guest spots from Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison and many more, is still the finest concert film ever made. He has directed lovely documentaries about George Harrison and the New York Review of Books; crime and music power his forays into TV, Boardwalk Empire and Vinyl. His own on-screen cameos have a selective symbolism, such the chilling murderer in the back of Travis Bickle’s cab or playing Vincent Van Gogh for his hero Akira Kurosawa.

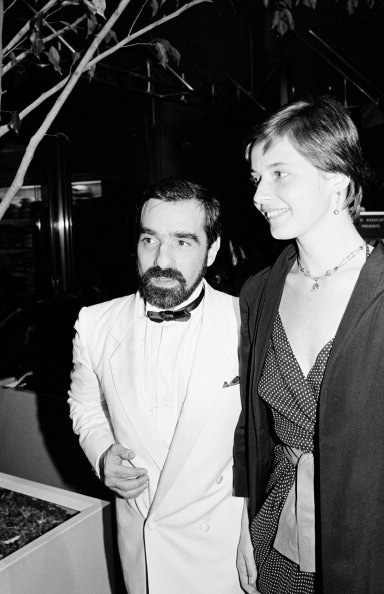

There’s so much life in his films that biographical context feels unnecessary, but echoes bounce between art and reality. Growing up “amongst gangsters and priests”, he worked as an altar boy and was tempted to work as a missionary. As a child he hated sport, was bedridden by asthma and had a fear of flying; as an adult he conquered addiction and has had five marriages, his third to Isabella Rossellini, the daughter of director Roberto Rossellini (another of his heroes) and Ingrid Bergman. An iconoclastic risk-taker, he is still banned from Tibet for Kundun, his 1997 film about the young Dalai Lama.

A profile in The New York Times suggested Scorsese’s youthful ardour stems from a “reverence for his elders”. His taste and influences bear this out: of his top ten films he submitted to Sight & Sound in 2012, the earliest comes from 1941 (Citizen Kane) and the latest from 1968 (2001: A Space Odyssey), with Fellini, Renoir and Powell & Pressburger in between. But he is also a progressive, as interested in descendants as ancestors. He taught Oliver Stone and Spike Lee at New York University, admires (amongst others) the British arthouse director Joanna Hogg, and once, when asked where to find the next Scorsese, pointed towards Wes Anderson.

In the rarefied position of basically being able to do what he wants (and rightly so), up next is The Irishman, an old-masters dream-team of Pacino, De Niro, Harvey Keitel and Joe Pesci. Another mooted project is a Rat Pack biopic, which the director would only want to make with Tom Hanks as Dean Martin, Jim Carrey as Jerry Lewis, John Travolta as Sinatra and Hugh Grant as Peter Lawford. He can afford to be picky. 75 this year, Martin Scorsese is the prodigal son turned elder statesman of American pop culture, a Catholic Rolling Stone, a cinema demigod destined for immortality. And yet, after various peaks and dips and brushes with death and rejuvenations, he keeps one eye ahead and one eye back. As Rupert Pupkin describes Jerry Lewis, Scorsese is still “as human as the rest of us, if not more so”.