The Line of Duty

The opening scene of the opening episode of the first season of The Crown makes it clear that Netflix’s juggernaut is unafraid to go straight for the Windsor jugular: here is a man, prostrate and ashen, coughing up blood into a toilet. The man is King George VI (played by Jared Harris). It would be wrong, however, to see this abject scene as some kind of supine metaphor for a reluctant and redundant reign. Despite George’s unlooked-for elevation from spare to heir, on the abdication of his brother Edward in December 1936, and the myriad ways he seemed unsuited to the role of sovereign — the retiring temperament, the crippling speech impediment, the fact that he’d never clapped eyes on a state paper — Britain’s previous king is now regarded as one of its greatest: punctilious, courageous and dedicated, and with a profound sense of duty. His 15 years on the throne saw him embody the stalwart defiance of the nation during the second world war, and skilfully navigate the seismic changes and privations that followed in its wake. “We are not a family, we are a firm,” he liked to say (a coinage that continues to this day, albeit in a more pejorative sense, as readers of Prince Harry’s recent memoir can attest). “The highest of distinction is service to others.”

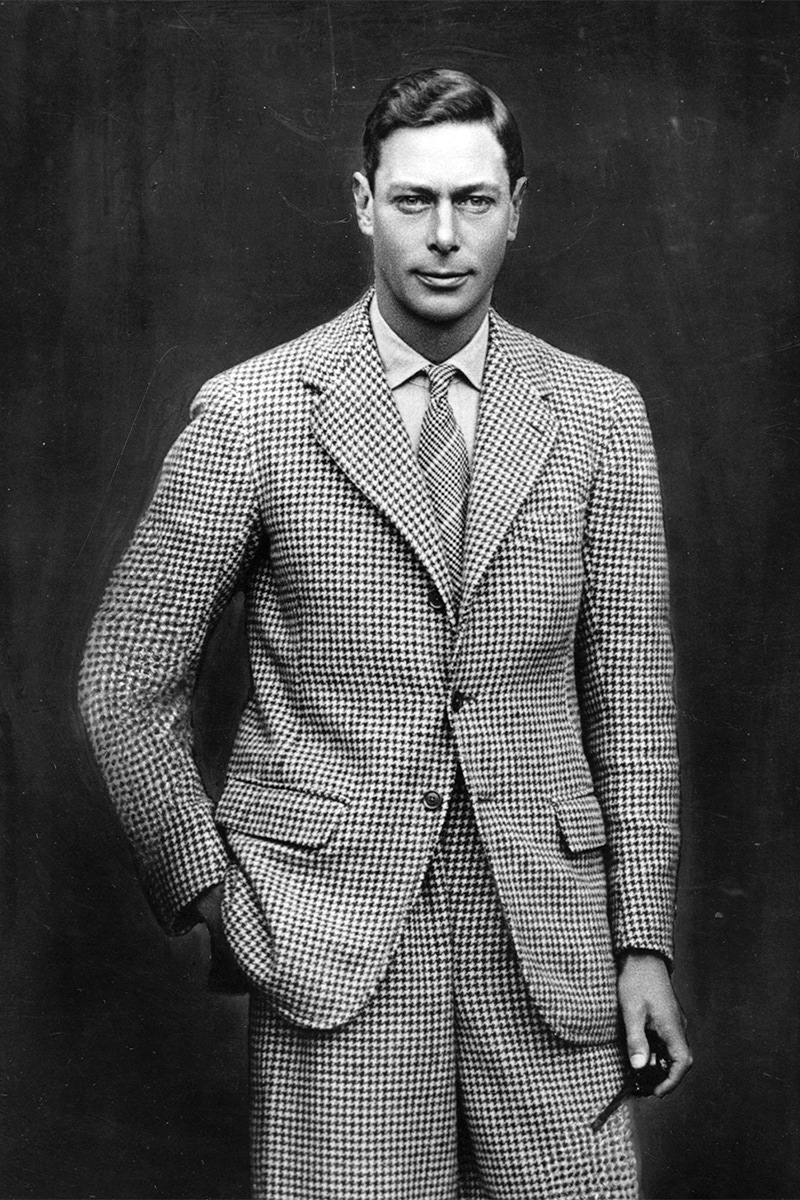

Unlike his elder brother, Bertie was allowed to see active service during the Great War, and found himself in the thick of the Battle of Jutland aboard HMS Collingwood as ‘Mr. Johnson’. He was the first member of the royal family to serve in the RAF and the first to qualify as a pilot. Despite assuming he would forever be in Edward’s shadow — “I simply always thought he was better and smarter than me,” he later said — Bertie was taller and more classically good-looking than the future Duke of Windsor, with a taut bone structure and piercing eyes. He was a gifted tennis player, even venturing onto the grass courts of the All England Club (he partnered Sir Louis Greig, then Duke of York, in the men’s doubles tournament at Wimbledon in 1926, only to be knocked out in the first round), and, as a ‘bachelor prince’, had a passionate affair with the musical- comedy and operetta star Evelyn Laye, which he broke off only on the promise of a dukedom of York from his father.

“This is a man,” averred Cecilia Bowes-Lyon, Countess of Strathmore, to Queen Mary, “who will be made or marred by his wife.” As it happened, Bertie had his eye on her daughter Elizabeth, who, loath to submit to the fishbowl of royal scrutiny, turned his proposal down three times. “She was frankly doubtful,” wrote Lady Airlie, who knew her well, “uncertain of her feelings, and afraid of the public life which would lie ahead of her.” But she succumbed to the prince’s fourth entreaty, and the couple was married at Westminster Abbey on April 26, 1923 (the clergy refused to allow a BBC broadcast of the ceremony, which would have been a first; the fear was that men might listen to it in pubs without doffing their hats).

Bertie needed all his reserves of those latter qualities when he faced the most daunting prospect of his life: the aftermath of his father’s unexpected death, in 1936, at the height of Edward’s amour fou with Wallis Simpson. He had scarcely a fortnight’s warning of the abdication, and had difficulty even securing an audience with his errant brother; meanwhile, so low was establishment confidence in Bertie that serious thought was given to bypassing both him and his charisma-free younger brother Henry and conferring the crown on George, Duke of Kent instead. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin eventually scuppered that notion — it seemed there were certain skeletons in George’s closet that would have made rather a racket had they come tumbling out — and Bertie was crowned King George VI (he chose the regnal name to stress continuity with his father) on May 12, 1937.

They were years in which the king’s own constitution proved far less robust than the post-war state he helped define; his lifetime of heavy smoking led to lung cancer arteries, and he was so weak by December 1951 that his Christmas address had to be pre-recorded in stages. He enjoyed a last day of shooting in the frosted fields of Sandringham on February 5, 1952, before retiring to bed spent and exultant. He was found dead of coronary thrombosis the next morning, aged 56. Churchill’s wreath at his funeral read, simply, “For valour”, while Clement Attlee extolled the fact that “he was always remarkably well informed... a conscientious monarch is a strong element of stability and continuity in our constitution” — words that could equally apply to George’s daughter, who kept a steady hand on the tiller for the better part of the next century. As the Firm prepares to anoint its first king in nearly nine decades, it’s safe to say that Charles III has not just one act but two very hard acts to follow.

Read the full story in Issue 87, available to purchase on TheRake.com and on newsstands worldwide now.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.